Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) was a landmark case in the fight for civil rights in the United States. The case established the constitutionality of laws mandating separate but equal public accommodations for African Americans and whites, giving constitutional sanction to state-sponsored segregation and racial discrimination. The Supreme Court's decision held that such laws did not impose a badge of servitude or infringe on the legal equality of Black Americans, as the accommodations were supposedly equal, and separateness did not imply inferiority. This ruling was based on the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause, which prohibits states from denying equal protection of the laws to any person within their jurisdiction. However, the separate but equal doctrine was later challenged and overturned in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), which outlawed segregated public education facilities for different races at the state and federal levels.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | May 18, 1896 |

| Case | Plessy vs. Ferguson |

| Court | U.S. Supreme Court |

| Decision | Racial segregation laws are constitutional as long as the facilities provided to each race are equal |

| Basis | Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause |

| Dissent | Justice John Marshall Harlan |

| Overturned by | Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) |

| Overturning opinion | "Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." |

| Overturning court | Warren Court |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The 'separate but equal' doctrine

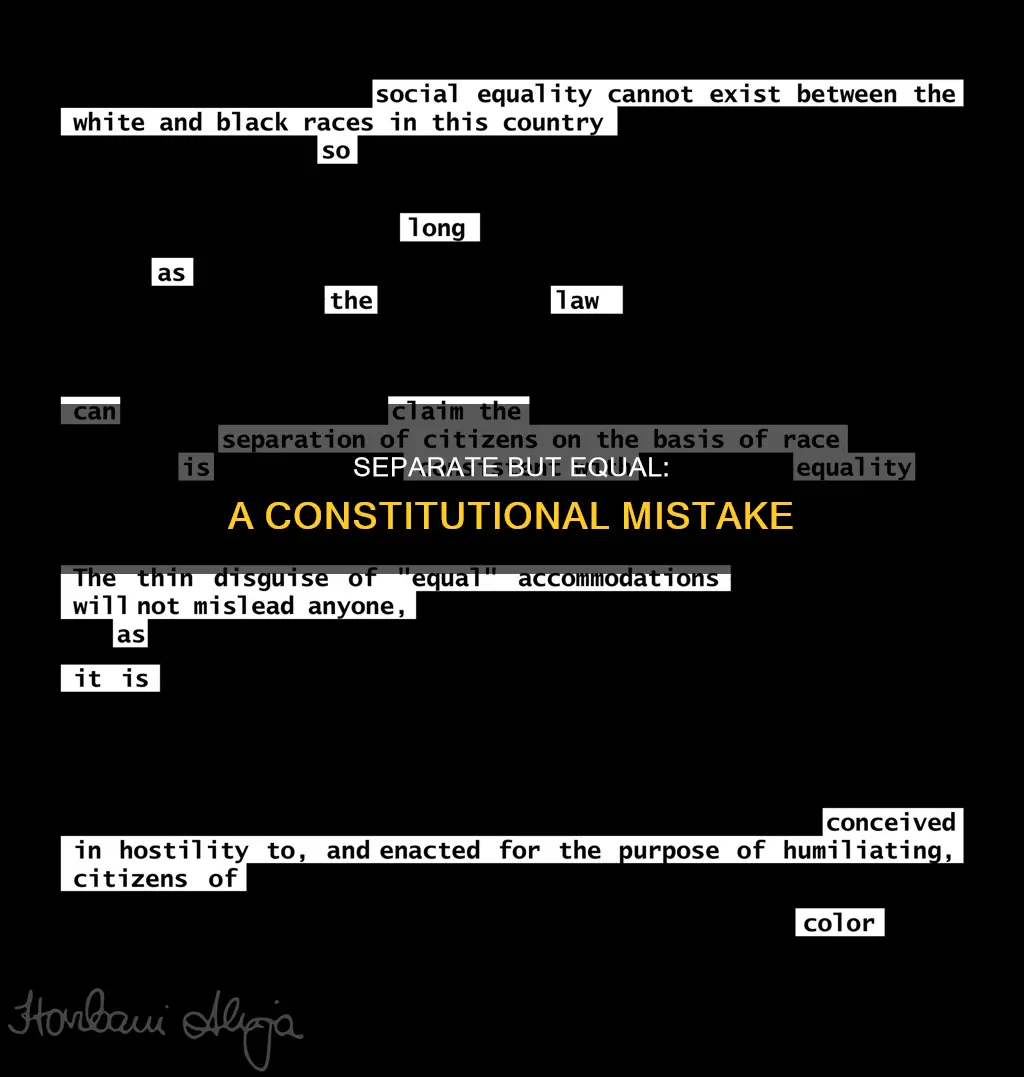

The "separate but equal" doctrine was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protection" under the law to all people. The doctrine was confirmed in the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision of 1896, which allowed state-sponsored segregation. The case arose out of an incident in 1892 in which Homer Plessy (seven-eighths white and one-eighth black) purchased a train ticket to travel within Louisiana and took a seat in a car reserved for white passengers. After refusing to move to a car for African Americans, he was arrested and charged with violating Louisiana's Separate Car Act.

In the majority opinion authored by Justice Henry Billings Brown, the Court held that the state law was constitutional. Justice Brown stated that, even though the Fourteenth Amendment intended to establish absolute equality for the races, separate treatment did not imply the inferiority of African Americans. The Court noted that there was no meaningful difference in equality between the white and the black railway cars, creating the doctrine later named "separate but equal". This doctrine gave constitutional sanction to laws designed to achieve racial segregation by means of separate and equal public facilities and services for African Americans and whites.

The "separate but equal" doctrine applied in theory to all public facilities: not only railroad cars but schools, medical facilities, theatres, restaurants, restrooms, and drinking fountains. However, the facilities and social services offered to African Americans were almost always of a lower quality than those offered to white Americans, if they existed at all. Most African-American schools had less public funding per student than nearby white schools, and they had old textbooks, used equipment, and poorly paid and prepared teachers.

In 1954, the "separate but equal" doctrine was eventually overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education. The unanimous (9-0) decision in Brown v. Board of Education, delivered by Chief Justice Earl Warren, overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, banning states from allowing segregation in public education and stating that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal". Warren wrote: "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal; segregation in public education is a denial of the equal protection of the laws." The decision in Brown v. Board remains a defining moment in U.S. history, providing a major catalyst for the civil rights movement and making possible advances in desegregating housing, public accommodations, and institutions of higher education.

God's View of Legal Marriage

You may want to see also

The Thirteenth Amendment

However, despite the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, the struggle for racial equality continued, as evident in the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896. Homer Plessy, a Black man, challenged the Separate Car Act, arguing that the Louisiana state law requiring railroads to provide separate accommodations for White and Black passengers violated his rights under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Supreme Court, in a 7-1 decision, ruled against Plessy, asserting that the law did not violate the Thirteenth Amendment as it only applied to slavery, and that separate but equal accommodations did not imply the inferiority of one race over the other.

The Plessy v. Ferguson decision set a precedent for the "separate but equal" doctrine, which allowed for racial segregation in public facilities as long as the accommodations provided to each race were deemed equal. This doctrine was used to justify segregation laws and practices across the country, particularly in the former Confederate states during the Jim Crow era. It is important to note that the "separate but equal" doctrine has been criticised for its failure to address the inherent inequality and discrimination perpetuated by segregation.

The "separate but equal" doctrine was eventually challenged and dismantled in the mid-20th century through a series of court cases. In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, overturning the precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson. The Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, recognised that segregation inherently violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, stating that "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place."

Additionally, in Bolling v. Sharpe (1954), the Court outlawed segregation in the District of Columbia, extending the reach of equal protection beyond the states. These landmark cases ushered in a period of liberal constitutional revolution, where racial segregation and the "separate but equal" doctrine were outlawed, and the civil rights of African Americans were increasingly recognised and protected under the law.

Understanding the Constitution: A Guide to Reading and Reviewing

You may want to see also

The Fourteenth Amendment

Despite the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantees, Southern states contended that the requirement of equality could be met in a way that kept the races separate. State and federal courts tended to reject pleas by African Americans that their Fourteenth Amendment rights were violated, arguing that the amendment applied only to federal laws and not to private persons or corporations. In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution allowed for segregation, as long as it was "separate but equal". This decision upheld a Louisiana state law that allowed for "equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races".

In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court unanimously declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, effectively ending the "separate but equal" doctrine. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in the court opinion: "We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place."

Illegal Hiring: What Practices Are Prohibited?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Civil Rights Act of 1875

> all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement; subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude.

The Act further provided that any person denied access to these facilities on account of race would be entitled to monetary restitution under a federal court of law.

Despite being signed into law, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was never effectively enforced. President Grant did nothing to enforce it, and his Justice Department ignored it. Federal judges called it unconstitutional, and in 1883, the Supreme Court declared sections of the Act unconstitutional in the Civil Rights Cases, finding that the Fourteenth Amendment did not give the federal government the power to prohibit discrimination by private individuals or corporations under the Equal Protection Clause.

Parts of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 were later re-adopted in the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, which relied on the Commerce Clause as the source of Congress's power to regulate private actors.

Understanding Coercion in New York: Financial Ruin as a Threat

You may want to see also

The end of 'separate but equal'

The "separate but equal" doctrine was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that allowed racial segregation as long as the facilities provided to each race were equal. This doctrine was based on the interpretation that racial segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed "equal protection" under the law to all people. The Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 confirmed this doctrine, allowing state-sponsored segregation.

However, the "separate but equal" doctrine was not truly equal in practice, and the treatment and facilities provided to Black citizens were often inferior. The doctrine was eventually challenged and overturned in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954. Led by Thurgood Marshall, who became the first Black Supreme Court Justice in 1967, the NAACP successfully argued that the "separate but equal" doctrine was unconstitutional.

In the Brown v. Board of Education case, the Supreme Court ruled that separating children in public schools based on race was unconstitutional and violated the Fourteenth Amendment. This decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement in the 1950s. The Warren Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, initiated a liberal constitutional revolution that outlawed racial segregation and "separate but equal" doctrines.

In addition to Brown v. Board of Education, other cases also contributed to the end of the "separate but equal" doctrine. Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, decided on the same day in 1950, effectively ended legal segregation in graduate and professional education. The companion case of Bolling v. Sharpe outlawed segregation in public education at the Federal level in the District of Columbia. These cases, along with Brown v. Board of Education, played a crucial role in dismantling the "separate but equal" doctrine and advancing racial integration in the United States.

Nevada's Constitution: A Historical Document

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

"Separate but equal" is a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that allowed racial segregation as long as the facilities provided to each race were equal. This doctrine was based on the interpretation that segregation laws did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause as long as they treated white and Black people equally.

The Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896 upheld a Louisiana state law that allowed for "separate but equal" accommodations for whites and Blacks, effectively establishing the constitutionality of racial segregation. This case emboldened segregationist states during the Jim Crow era and prevented constitutional challenges to segregation for over half a century.

The "separate but equal" doctrine was effectively overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954. Led by Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP successfully challenged the constitutionality of "separate but equal," outlawing segregated public education facilities for Blacks and whites at the state and federal levels.

![Separate But Equal [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71DEmkVoPtL._AC_UY218_.jpg)