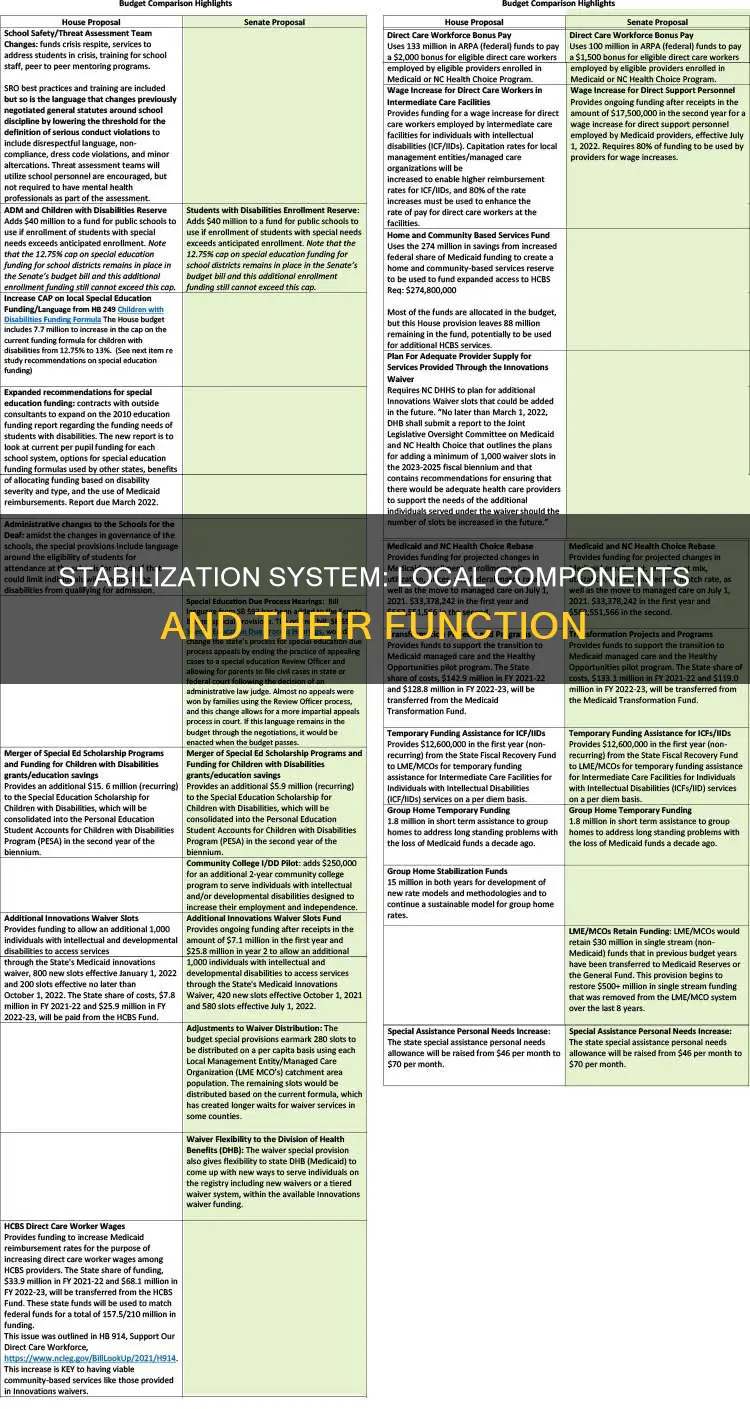

The core muscles can be categorized into three different systems: the local stabilization system, the global stabilization system, and the movement system. The local stabilization system is made up of muscles that attach directly to the vertebrae, primarily consisting of type 1 (slow-twitch) muscle fibers with a high density of muscle spindles. These muscles include the transverse abdominis, internal obliques, multifidus, pelvic floor musculature, and diaphragm. They work together to stabilize the vertebral column and protect the spinal cord, while also limiting excessive forces between spinal segments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Primary muscles | Transverse abdominis, internal obliques, multifidus, pelvic floor musculature, and diaphragm |

| Muscle fiber type | Type 1 (slow twitch) muscle fibers with a high density of muscle spindles |

| Function | Intervertebral and intersegmental stability, limiting excessive compressive, shear, and rotational forces between spinal segments |

| Exercises | Ball crunch, back extensions, reverse crunch, cable rotations, prone iso-abs (planks) |

Explore related products

Transverse abdominis

The transverse abdominal muscle (TVA), also known as the transverse abdominis, transversalis muscle, and transversus abdominis muscle, is a muscle layer of the front and side abdominal wall. It is a deep abdominal muscle and an important core muscle. It is positioned deep to the internal oblique muscle.

The TVA serves to compress and retain the contents of the abdomen, as well as assist in exhalation. It can contract during the exhalation phase of respiration to force air out of the thorax. It also helps a pregnant person deliver a child. The TVA is vital to back and core health, and it has the effect of pulling in what would otherwise be a protruding abdomen, hence its nickname, the "corset muscle". Training the TVA helps flatten the belly, which cannot be achieved by training the rectus abdominis muscles alone.

The TVA has several origin points: the lateral one-third of the superior surface of the inguinal ligament and the associated iliac fascia; the anterior two-thirds of the inner lip of the iliac crest; the thoracolumbar fascia between the iliac crest and the 12th rib; the internal aspects of the lower six ribs and their costal cartilages. From these origin points, the TVA fibres course horizontally over the lateral abdominal wall towards the midline, oriented perpendicular to the linea alba.

The TVA is innervated by the lower intercostal nerves (thoracoabdominal, nerve roots T7-T11), as well as the iliohypogastric nerve and the ilioinguinal nerve. It is mainly supplied by the terminal branches of the lower five intercostal nerves and the subcostal nerve, arising from the lower six thoracic spinal nerves (T7-T12).

Georgia Constitution: A Comprehensive Document of Pages

You may want to see also

Internal obliques

The internal abdominal oblique is a broad, thin muscle found on the lateral side of the abdomen. It forms one of the three layers of the lateral abdominal wall, along with the external oblique on the outer side and the transverse abdominis on the inner side. The internal abdominal oblique is deeper than the external abdominal oblique and more superficial than the transverse abdominis.

The internal abdominal oblique has multiple sites of origin, distributed along the anterolateral side of the trunk. The anterior fibres of the internal abdominal oblique arise from a deep structure known as the iliopectineal arch. These fibres pass inferomedially, arching over the inguinal canal and merging with the tendinous fibres of the transversus abdominis to form the conjoint tendon. The lateral fibres of the internal abdominal oblique are continuous with the rectus sheath, a large aponeurosis of the anterior abdominal wall.

The internal abdominal oblique is important for maintaining normal abdominal tension and increasing intra-abdominal pressure. It helps facilitate movements of the trunk, such as ipsilateral rotation and side-bending, by working with other abdominal muscles. For example, the contraction of the right internal oblique and the left external oblique allow the torso to flex and rotate, bringing the left shoulder towards the right hip.

The internal obliques are considered core stabilising muscles and are part of the local stabilisation system. They contribute to spinal stability by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and generating tension in the thoracolumbar fascia, thereby increasing spinal stiffness and improving neuromuscular control.

Constitution's Philosophical Roots: Ideological Underpinnings Explored

You may want to see also

Multifidus

The multifidus muscle is a group of short, triangular muscles that are part of the transversospinalis muscle group. It is located in the third or deep layer of deep muscles of the back, lying deep to the erector spinae, semispinalis, and thoracis, and superficial to the rotatores muscles. The multifidus muscle is connected to the transverse abdominis via the thoracolumbar fascia.

The multifidus muscle spans the entire length of the vertebral column, from the cervical to the lumbar spine, and is most developed in the lumbar area. It is composed of several fleshy and tendinous fasciculi, which fill the groove on either side of the spinous processes of the vertebrae. Although the multifidus muscle is very thin, it is an important stabilizer of the lumbar spine and plays a crucial role in static and dynamic spinal stability. It functions alongside the transversus abdominis and pelvic floor muscles to provide spine stability.

Bilateral contraction of the multifidus muscle results in the extension of the vertebral column, while unilateral contraction leads to lateral flexion of the spine to the same side and rotation to the opposite side. The unique design of the multifidus provides it with extra strength, allowing it to stabilize the vertebrae during trunk rotation. When the oblique abdominal muscles contract and produce trunk rotation, the multifidus muscles oppose the trunk flexion, maintaining a pure axial rotation.

Weakness or dysfunction in the lumbar multifidus muscle is associated with low back pain. Core stabilization programs that focus on increasing the cross-sectional area of the multifidus muscle can help reduce low back pain. Dry needling of the multifidus trigger points has been found to increase the thickness of the transversus abdominis during contraction, indicating its potential for treating low back pain.

Saddle Tree Width: Understanding Narrow Tree Fit

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.23 $19.87

Pelvic floor musculature

Pelvic floor muscles are a group of muscles that form the base of the core muscles. They stretch from the pubic bone in the front of the body to the tailbone (coccyx) in the back, extending outward on both sitting bones (ischial tuberosity) on the right and left sides of the pelvis. The pelvic floor muscles intertwine to form a single sheet of layered muscle with openings for the anus, urethra, and vagina. These muscles support important organs in the pelvis, including the bladder, bowel (large intestine), and internal reproductive organs, by holding them in place and providing flexibility for bodily functions.

Pelvic floor muscles are part of the local stabilization system, which includes deep muscles such as the multifidus, transversus abdominis, diaphragm, and pelvic floor muscles. These muscles contribute to spinal stability by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and generating tension in the thoracolumbar fascia, thereby increasing spinal stiffness for improved intersegmental neuromuscular control.

The pelvic floor muscles can weaken over time due to various factors, including injury, childbirth, surgery, and the natural aging process. Conditions like diabetes may also contribute to muscle weakness. Weakened pelvic floor muscles can lead to conditions such as incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. However, exercising these muscles can help combat the negative effects of weakness.

Pelvic floor muscle control, the ability to squeeze and relax these muscles, is essential for bowel and bladder function. Squeezing the muscles narrows the passages, preventing waste material from escaping. Conversely, relaxing the muscles widens the passages, allowing for urination or defecation.

In summary, the pelvic floor musculature is a crucial component of the local stabilization system, providing core stability, protecting vital organs, and facilitating essential bodily functions through coordinated muscle control.

The Constitution and Declaration: Where Are They Now?

You may want to see also

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a primary muscle of respiration that separates the abdominal and thoracic cavities. It is a local stabilizer muscle that increases intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) and generates tension in the thoracolumbar fascia (connective tissue of the low back), thereby increasing spinal stiffness and improving intersegmental neuromuscular control. The diaphragm, along with the pelvic floor muscles, contributes to trunk stability as part of the local muscle system.

The diaphragm's role in trunk stability is particularly important for individuals with low back pain, gait or balance dysfunction, and those who have been on mechanical ventilation. Its function in maintaining lumbar spinal stability involves minimizing displacement of the abdominal contents into the thorax through increased IAP. This simultaneous stabilization and ventilation function of the diaphragm is activated in response to voluntary movements of the limbs.

The diaphragm is one of the deep layer muscles that make up the local stabilization system, along with the lumbar multifidus, transversus abdominis, and pelvic floor muscles. These muscles work together to stabilize the segments in relation to each other, providing support from vertebra to vertebra. The local stabilizers also limit excessive compressive, shear, and rotational forces between spinal segments, protecting the spinal cord.

Marines' Constitution: Fundamentals for Leading Marines

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Transverse abdominis, internal obliques, multifidus, pelvic floor musculature, and diaphragm.

Type 1: Slow-twitch muscle fibers with a high density of muscle spindles.

Excessive compressive, shear, and rotational forces between spinal segments.

They provide support from vertebra to vertebra.

Prone iso-abs (planks).