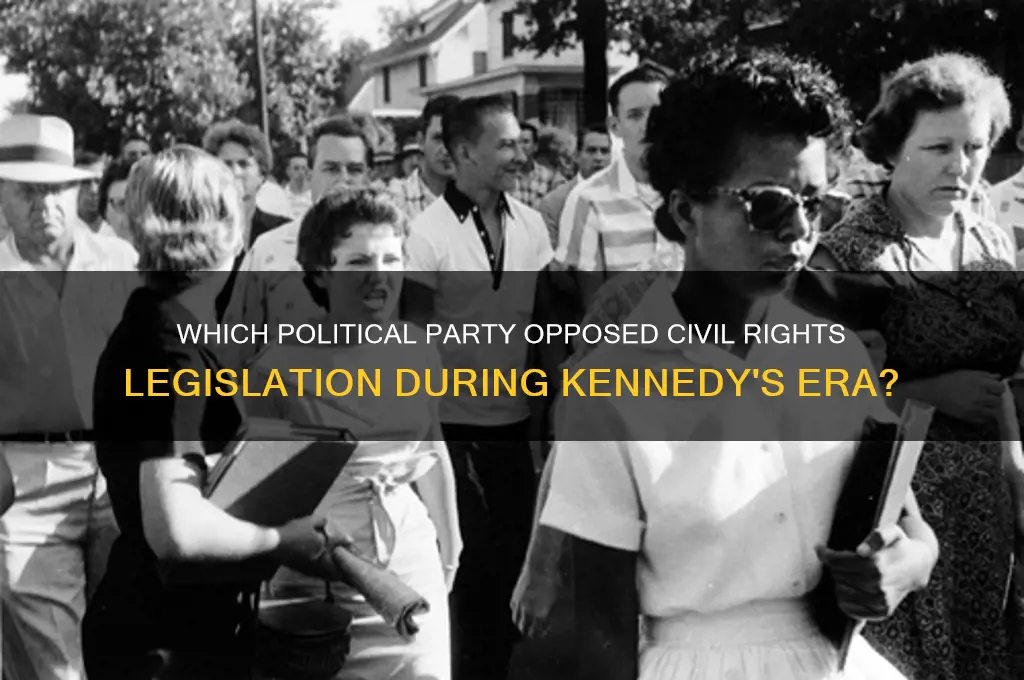

The question of which of Kennedy's political parties opposed civil rights legislation delves into a complex historical context, as it involves examining the stances of both the Democratic and Republican parties during the mid-20th century. While John F. Kennedy, a Democrat, supported civil rights and pushed for federal legislation, the reality was that significant opposition to such measures came from conservative Democrats, particularly those in the South, who formed the Dixiecrat bloc. These Southern Democrats staunchly resisted desegregation and voting rights for African Americans, often aligning with conservative Republicans on these issues. Conversely, the national Democratic Party, under Kennedy's leadership, increasingly embraced civil rights, while the Republican Party, though divided, had a more moderate to progressive wing that supported civil rights legislation. Thus, the opposition to civil rights within Kennedy's political landscape was primarily rooted in the conservative Southern wing of his own Democratic Party rather than the Republicans as a whole.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Southern Democrats (Dixiecrats) |

| Stance on Civil Rights Legislation | Opposed |

| Key Figures | Strom Thurmond, James Eastland, George Wallace |

| Region of Influence | Southern United States |

| Primary Opposition | Federal civil rights bills, desegregation, voting rights for African Americans |

| Tactics | Filibusters, obstruction, states' rights arguments |

| Historical Context | 1950s-1960s, during the Civil Rights Movement |

| Impact | Delayed passage of key civil rights laws, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 |

| Ideological Basis | Segregation, white supremacy, resistance to federal intervention |

| Legacy | Contributed to the realignment of the Democratic and Republican parties in the South |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Southern Democrats' Resistance: Many Southern Democrats opposed civil rights, fearing racial integration and federal intervention

- Conservative Coalition: A bloc of Southern Democrats and Republicans blocked civil rights bills in Congress

- States' Rights Argument: Opponents claimed civil rights laws infringed on states' autonomy and local control

- Economic Concerns: Fear of economic disruption and job competition fueled opposition in some regions

- Kennedy's Challenges: Despite support, Kennedy faced resistance within his own party on civil rights

Southern Democrats' Resistance: Many Southern Democrats opposed civil rights, fearing racial integration and federal intervention

During the mid-20th century, a significant faction within the Democratic Party, particularly in the South, staunchly resisted civil rights legislation. This resistance was rooted in deep-seated fears of racial integration and federal intervention, which Southern Democrats viewed as threats to their way of life and regional autonomy. Their opposition was not merely ideological but also strategic, as they sought to maintain the racial hierarchy that had long underpinned Southern society. By filibustering key bills and leveraging their influence in Congress, these Democrats delayed the passage of landmark civil rights laws, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

To understand this resistance, consider the historical context. The Solid South, a term describing the Democratic dominance in Southern states since Reconstruction, was built on a foundation of racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Southern Democrats feared that federal civil rights legislation would dismantle this system, leading to integrated schools, workplaces, and public spaces. For example, Senator Richard Russell of Georgia famously declared, "We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our [Southern] states." This sentiment was widespread among Southern Democrats, who saw integration as a cultural and social invasion.

The tactics employed by Southern Democrats to block civil rights legislation were both systematic and relentless. They used the Senate’s filibuster rule to indefinitely prolong debates, effectively killing bills that lacked the two-thirds majority needed to invoke cloture. In 1964, for instance, Southern senators filibustered the Civil Rights Act for 57 days, the longest filibuster in Senate history at the time. Additionally, they formed the Southern Manifesto in 1956, a congressional resolution condemning the Supreme Court’s *Brown v. Board of Education* decision and pledging to resist its implementation. These actions highlight the lengths to which Southern Democrats went to preserve segregation and resist federal authority.

Despite their efforts, the resistance of Southern Democrats ultimately proved unsustainable. The growing national consensus in favor of civil rights, coupled with the moral leadership of figures like President Lyndon B. Johnson, led to the passage of key legislation. However, the legacy of this resistance is still felt today. Many Southern Democrats, disillusioned with their party’s shift toward civil rights, began to align with the Republican Party, a phenomenon known as the "Southern Strategy." This realignment reshaped American politics, turning the South into a Republican stronghold and leaving a lasting impact on the nation’s political landscape.

In practical terms, understanding this resistance offers valuable lessons for contemporary efforts to advance social justice. It underscores the importance of coalition-building and the need to address regional and ideological divides. Advocates for change must recognize that opposition often stems from deeply ingrained fears and interests, requiring strategies that not only challenge these views but also offer alternatives that address underlying concerns. By studying the Southern Democrats’ resistance, we gain insights into the complexities of political change and the enduring struggle for equality.

Discover Your Political Identity: Uncover Your Core Beliefs and Values

You may want to see also

Conservative Coalition: A bloc of Southern Democrats and Republicans blocked civil rights bills in Congress

During the mid-20th century, a powerful alliance known as the Conservative Coalition emerged in Congress, uniting Southern Democrats and Republicans in opposition to civil rights legislation. This bloc exploited procedural rules, particularly the Senate filibuster, to stall or kill bills aimed at ending racial segregation and discrimination. Their tactics effectively delayed landmark measures like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which required supermajorities to overcome. By prioritizing states' rights and maintaining the racial status quo, the Conservative Coalition became a formidable obstacle to progress, illustrating how partisan and regional interests can thwart federal reform.

To understand the Coalition’s impact, consider the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the first such bill passed since Reconstruction. Southern Democrats, fearing federal intervention in state affairs, watered down the legislation, stripping it of enforcement mechanisms. This pattern repeated in 1960, when the Coalition again weakened a civil rights bill, rendering it largely symbolic. Their strategy relied on unity across party lines: Southern Democrats brought regional solidarity, while Republicans, particularly those from the Midwest and West, often aligned with their fiscal conservatism and states' rights arguments. This alliance highlights how ideological overlap can transcend party divisions, even on morally charged issues.

The filibuster became the Coalition’s weapon of choice, as it required 60 votes to end debate in the Senate. In 1964, Southern senators launched a 75-day filibuster against the Civil Rights Act, the longest in U.S. history at the time. This procedural maneuver forced supporters to build a broad coalition, including liberal Republicans like Everett Dirksen, whose support was critical to securing passage. The filibuster’s role underscores the importance of procedural rules in shaping policy outcomes, as well as the need for strategic alliances to overcome entrenched opposition.

Despite their successes, the Conservative Coalition’s influence began to wane in the late 1960s. The passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 marked a turning point, as it empowered African American voters and shifted political dynamics in the South. Simultaneously, the Democratic Party’s growing commitment to civil rights alienated many Southern conservatives, who gradually migrated to the Republican Party. This realignment, known as the Southern Strategy, transformed the GOP into a bastion of conservatism in the region, while Democrats became more closely associated with civil rights. The Coalition’s legacy thus includes not only the delay of civil rights but also the reshaping of American political parties.

For those studying legislative history or advocating for reform today, the Conservative Coalition offers critical lessons. First, procedural rules like the filibuster can be exploited to block progress, necessitating strategic countermeasures. Second, cross-party alliances, though often ideologically driven, can be more durable than expected, particularly when rooted in regional interests. Finally, the Coalition’s eventual decline demonstrates that demographic and political shifts can erode even the most entrenched opposition. Understanding these dynamics provides a roadmap for navigating contemporary legislative battles, where similar coalitions may form around issues like immigration, climate change, or voting rights.

Exploring the Rise of Single-Issue Political Parties and Their Impact

You may want to see also

States' Rights Argument: Opponents claimed civil rights laws infringed on states' autonomy and local control

The States Rights Argument was a cornerstone of opposition to civil rights legislation during the Kennedy era, rooted in the belief that federal intervention in matters of race and equality overstepped constitutional boundaries. Opponents, primarily from the Southern wing of the Democratic Party, argued that such laws infringed upon the sovereignty of individual states, which they claimed had the authority to regulate social and political affairs without federal oversight. This stance was not merely a legal technicality but a deeply entrenched ideological position that sought to preserve the status quo of racial segregation and local control.

To understand the argument, consider the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which reserves powers not granted to the federal government to the states or the people. Opponents of civil rights legislation seized on this amendment to assert that issues like voting rights, public accommodations, and education were state matters. For example, when the Kennedy administration proposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Southern Democrats like Senator Richard Russell of Georgia vehemently opposed it, claiming it violated states’ rights by imposing federal standards on local institutions. This perspective framed civil rights as a federal overreach rather than a necessary correction of systemic injustice.

The States Rights Argument was not just a legal doctrine but a political strategy to maintain racial segregation. By framing the debate as a defense of state autonomy, opponents sought to appeal to broader concerns about federal power, even among those who might not explicitly support segregation. This tactic allowed them to garner support beyond the South, tapping into fears of centralized government and the erosion of local traditions. For instance, the 1964 act’s provisions on desegregating public spaces were portrayed as an attack on Southern culture and self-governance, rather than a step toward equality.

However, this argument was fundamentally flawed in its application to civil rights. The Constitution’s Commerce Clause and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal protection under the law, provided clear legal grounds for federal intervention. The Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in *Brown v. Board of Education* further undermined the States Rights Argument by establishing that state-sanctioned segregation violated constitutional rights. Despite these legal precedents, opponents continued to wield the argument as a shield, highlighting the tension between federal authority and state sovereignty in American political discourse.

In practice, the States Rights Argument delayed progress on civil rights for years, as Southern politicians used filibusters and other procedural tactics to block legislation. It also exposed the limitations of relying solely on legal frameworks to address moral issues. While the argument purported to defend state autonomy, its true purpose was to preserve racial inequality. Today, echoes of this argument persist in debates over federal versus state authority, serving as a reminder of how legal principles can be manipulated to resist social change. Understanding this historical context is crucial for navigating contemporary discussions on federalism and justice.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in Rome 2: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Economic Concerns: Fear of economic disruption and job competition fueled opposition in some regions

During the 1960s, as President John F. Kennedy and later his successor Lyndon B. Johnson pushed for civil rights legislation, a significant portion of the opposition came from within their own Democratic Party, particularly in the South. Economic concerns played a pivotal role in this resistance, as many feared that integrating workplaces and public spaces would disrupt local economies and intensify job competition. This fear was not merely abstract; it was deeply rooted in the socioeconomic realities of regions heavily reliant on low-wage labor and segregated industries.

Consider the agricultural sector in states like Mississippi and Alabama, where sharecropping and tenant farming systems depended on cheap, often exploited Black labor. White farmers and landowners feared that civil rights reforms, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act, would raise wages and erode their economic advantage. Similarly, in urban areas, white workers in industries like textiles and manufacturing worried that desegregation would open jobs to Black workers, potentially driving down wages or displacing them entirely. These anxieties were amplified by politicians who framed civil rights as an economic threat, rather than a moral imperative.

The opposition was not just about immediate job loss but also about long-term economic restructuring. For instance, in cities like Birmingham, Alabama, where steel and mining industries dominated, white workers viewed desegregation as a precursor to unionization efforts that could further destabilize their employment. This fear was often stoked by business leaders who argued that civil rights legislation would increase operational costs, making Southern industries less competitive nationally. Such arguments resonated deeply in communities where economic survival was already precarious, creating a powerful alliance between working-class whites and conservative business interests.

To understand the depth of this opposition, examine the role of local media and political rhetoric. Newspapers in Southern states frequently published articles warning of economic collapse if civil rights bills passed, while politicians like Senator James Eastland of Mississippi explicitly linked desegregation to unemployment. These narratives were not always based on factual economic analysis but were effective in mobilizing opposition. For example, in 1964, during the debate over the Civil Rights Act, a survey found that 60% of white Southerners believed the legislation would harm the economy, even though studies later showed minimal negative impact on employment rates.

Practical steps to address these economic fears were often overlooked in the broader civil rights debate. Had policymakers paired civil rights legislation with targeted economic programs—such as job retraining initiatives or infrastructure investments in underserved communities—they might have mitigated some of the opposition. Instead, the lack of such measures allowed economic anxieties to fester, reinforcing regional divides. This oversight serves as a cautionary tale for modern policymakers: addressing economic concerns head-on is essential when advocating for social justice reforms.

In conclusion, the economic fears that fueled opposition to civil rights legislation within Kennedy’s Democratic Party were deeply intertwined with regional labor dynamics and political manipulation. By understanding these specific concerns—from agricultural exploitation to industrial competition—we gain insight into why progress was so fiercely resisted in certain regions. This historical lesson underscores the importance of coupling social reforms with economic strategies to ensure broader acceptance and sustainability.

Endorsements and Funding: Powering Political Parties' Campaigns and Influence

You may want to see also

Kennedy's Challenges: Despite support, Kennedy faced resistance within his own party on civil rights

John F. Kennedy’s presidency is often remembered for its bold vision of progress, yet his push for civil rights legislation reveals a complex struggle within his own Democratic Party. While Kennedy publicly championed equality, a significant faction of Southern Democrats, known as Dixiecrats, staunchly opposed federal intervention in racial matters. These lawmakers, deeply rooted in segregationist ideologies, wielded considerable power in Congress, chairing key committees and leveraging procedural tactics to stall civil rights bills. Kennedy’s challenge was not merely ideological but structural: he had to navigate a party divided by regional interests, where Southern Democrats viewed civil rights as a threat to their political and social dominance.

Consider the 1963 Civil Rights Act, a cornerstone of Kennedy’s agenda. Despite its moderate provisions—banning segregation in public places and discrimination in employment—Southern Democrats filibustered the bill for 75 days, the longest in Senate history at the time. Senators like Richard Russell of Georgia and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina led the charge, arguing states’ rights and economic disruption. Kennedy’s strategy involved both negotiation and pressure. He courted moderate Republicans for bipartisan support while privately urging Northern Democrats to prioritize the bill. Yet, even with these efforts, the bill’s passage remained uncertain until Lyndon B. Johnson’s leadership after Kennedy’s assassination.

The resistance within the Democratic Party highlights a paradox: Kennedy’s own coalition included those who actively undermined his goals. Southern Democrats, a critical voting bloc for decades, saw civil rights as an existential threat. Kennedy’s attempts to balance party unity and moral leadership often meant compromising on the pace and scope of reform. For instance, he initially avoided direct confrontation on issues like voting rights, fearing alienating Southern allies. This cautious approach frustrated civil rights activists, who demanded bolder action, while Southern Democrats remained unmoved by incremental changes.

A practical takeaway from this historical tension is the importance of understanding intra-party dynamics in policy-making. Kennedy’s experience underscores that even well-intentioned leaders must confront entrenched interests within their own ranks. For modern advocates, this means mapping power structures, identifying key opponents, and building coalitions that transcend regional or ideological divides. Kennedy’s struggle also reminds us that progress often requires both public advocacy and behind-the-scenes negotiation—a delicate balance between principle and pragmatism.

In retrospect, Kennedy’s challenges within his party reveal the fragility of progress in the face of deep-seated resistance. His presidency demonstrates that even when a leader’s vision aligns with broader societal values, institutional barriers and internal opposition can slow or derail reform. For those working toward systemic change today, the lesson is clear: success demands not just bold ideas but a strategic understanding of the forces that sustain the status quo. Kennedy’s legacy in civil rights is not just one of triumph but of the persistent effort required to bridge divides within one’s own camp.

Electoral Realignments: Transforming Party Politics and Shaping New Political Landscapes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Southern Democrats, a faction within the Democratic Party, were the primary opponents of civil rights legislation during John F. Kennedy's presidency.

Many Southern Democrats opposed civil rights legislation because they feared it would disrupt the segregationist policies and social order in the South, which they had long supported.

Kennedy strategically worked to build coalitions and used his political influence to gradually gain support for civil rights, often balancing the demands of Southern Democrats with the need for progress on racial equality.