The New Deal, a series of programs and reforms implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression, is inherently political due to its transformative impact on American society, economy, and government. While primarily aimed at economic recovery, the New Deal also reshaped the role of the federal government, expanding its authority and establishing a social safety net. This shift sparked intense political debates, with supporters hailing it as a necessary intervention to address widespread suffering and critics condemning it as an overreach of federal power. Programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps, Social Security, and the National Recovery Administration became battlegrounds for competing visions of governance, individual rights, and the proper role of the state, cementing the New Deal’s legacy as a profoundly political endeavor.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Roosevelt's Political Strategy: How FDR used the New Deal to build a new Democratic coalition

- Conservative Backlash: Opposition from Republicans and conservative Democrats to New Deal policies

- Court Packing Plan: FDR's attempt to reshape the Supreme Court to favor New Deal laws

- Labor Unions' Rise: New Deal policies empowering unions and their political influence

- Southern Democrats' Shift: The New Deal's impact on the Solid South's political alignment

Roosevelt's Political Strategy: How FDR used the New Deal to build a new Democratic coalition

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal was not merely a series of economic reforms to combat the Great Depression; it was a masterclass in political strategy aimed at reshaping the Democratic Party and solidifying its dominance in American politics. FDR understood that to achieve lasting political power, he needed to build a broad and durable coalition that transcended traditional Democratic constituencies. The New Deal became the vehicle through which he achieved this, by appealing to diverse groups and redefining the role of government in American society.

One of FDR’s key political strategies was to expand the Democratic Party’s base by incorporating marginalized groups into its coalition. Prior to the New Deal, the Democratic Party relied heavily on the Solid South, urban machine politics, and rural farmers. FDR, however, recognized the potential of new constituencies, particularly organized labor, ethnic minorities, and African Americans. Through programs like the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Wagner Act, which protected workers’ rights to unionize, FDR gained the loyalty of the labor movement. Similarly, his administration’s relief programs, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), provided jobs to millions of unemployed Americans, including African Americans, who began to shift their allegiance from the Republican Party to the Democrats.

Another critical aspect of FDR’s strategy was his ability to communicate directly with the American people, fostering a sense of trust and shared purpose. His Fireside Chats, delivered via radio, humanized the presidency and made government policies accessible to ordinary citizens. By framing the New Deal as a collective effort to combat economic hardship, FDR created a narrative of national unity that resonated across demographic lines. This communication strategy not only bolstered public support for his policies but also cemented his image as a compassionate and decisive leader.

FDR also used the New Deal to redefine the Democratic Party’s ideological stance, positioning it as the party of activism and government intervention. By contrast, he painted the Republican Party as indifferent to the struggles of ordinary Americans. Programs like Social Security, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) demonstrated the federal government’s capacity to address systemic issues and improve people’s lives. This shift in ideology not only distinguished the Democrats from the Republicans but also laid the groundwork for the modern welfare state, ensuring the party’s relevance for decades to come.

Finally, FDR’s political strategy involved institutionalizing the New Deal coalition through strategic appointments and party reorganization. He appointed allies to key positions within the government and the Democratic National Committee, ensuring that the party machinery reflected his vision. Additionally, he worked to weaken the influence of conservative Southern Democrats, who opposed many of his progressive policies, by building alliances with Northern liberals and urban Democrats. This internal realignment within the party was crucial in maintaining the coalition’s cohesion and ensuring its longevity.

In conclusion, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was a political masterpiece that transformed the Democratic Party into a dominant force in American politics. By expanding its base, redefining its ideology, and fostering a direct connection with the American people, FDR built a coalition that would shape the nation’s political landscape for generations. His strategic use of the New Deal not only addressed the economic crisis of the Great Depression but also redefined the relationship between the government and its citizens, leaving an indelible mark on American history.

Identity Politics: Unmasking the Racist Underbelly of Division and Exclusion

You may want to see also

Conservative Backlash: Opposition from Republicans and conservative Democrats to New Deal policies

The New Deal, implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in response to the Great Depression, was a series of programs and policies aimed at relief, recovery, and reform. While it garnered significant support, it also faced fierce opposition, particularly from Republicans and conservative Democrats. This conservative backlash was rooted in ideological differences, economic concerns, and fears of expanding federal power. Many conservatives viewed the New Deal as a radical departure from traditional American values of limited government and individual initiative, labeling it as socialist or even communist.

One of the primary criticisms from conservatives was the unprecedented expansion of federal authority under the New Deal. Programs like the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) were seen as overreaching interventions into the private sector. Republicans and conservative Democrats argued that these policies undermined free-market principles and stifled business growth. The Supreme Court, influenced by conservative justices, struck down several New Deal programs, including the NRA, in cases like *Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States* (1935), further fueling conservative opposition.

Economic concerns also drove the backlash. Conservatives feared that the New Deal’s emphasis on deficit spending and government intervention would lead to long-term economic instability. They criticized policies like Social Security and unemployment insurance as unaffordable and unsustainable. Additionally, Southern Democrats, who were often conservative, opposed labor reforms such as the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) because they threatened the region’s low-wage, anti-union economic model. These economic arguments were coupled with racial anxieties, as Southern conservatives feared federal labor protections would empower African American workers.

Political tactics played a significant role in the conservative backlash. Republicans, led by figures like Alf Landon and Robert Taft, framed the New Deal as a threat to individual liberty and states’ rights. They accused Roosevelt of concentrating too much power in the executive branch, a critique that resonated with many Americans wary of federal overreach. Conservative Democrats, often referred to as the “conservative coalition,” formed alliances with Republicans in Congress to block or water down New Deal legislation. This coalition effectively stalled progressive reforms in the late 1930s and beyond, shaping the political landscape for decades.

Finally, the cultural and social implications of the New Deal fueled conservative opposition. Traditionalists viewed programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) as promoting dependency on government rather than self-reliance. They also criticized the New Deal’s support for organized labor, seeing it as a threat to business interests and social order. This cultural critique was often intertwined with anti-intellectualism, as conservatives dismissed New Deal planners and experts as out-of-touch elites. The backlash against the New Deal thus reflected broader tensions between progressive and conservative visions of America’s future.

In summary, the conservative backlash to the New Deal was multifaceted, driven by concerns over federal power, economic sustainability, and cultural values. Republicans and conservative Democrats mobilized politically, legally, and rhetorically to challenge Roosevelt’s policies, shaping a lasting divide in American politics. Their opposition not only limited the scope of the New Deal but also laid the groundwork for future conservative movements that continue to debate the role of government in society.

Who Started Politico Playbook: Uncovering the Origins of Political Insider News

You may want to see also

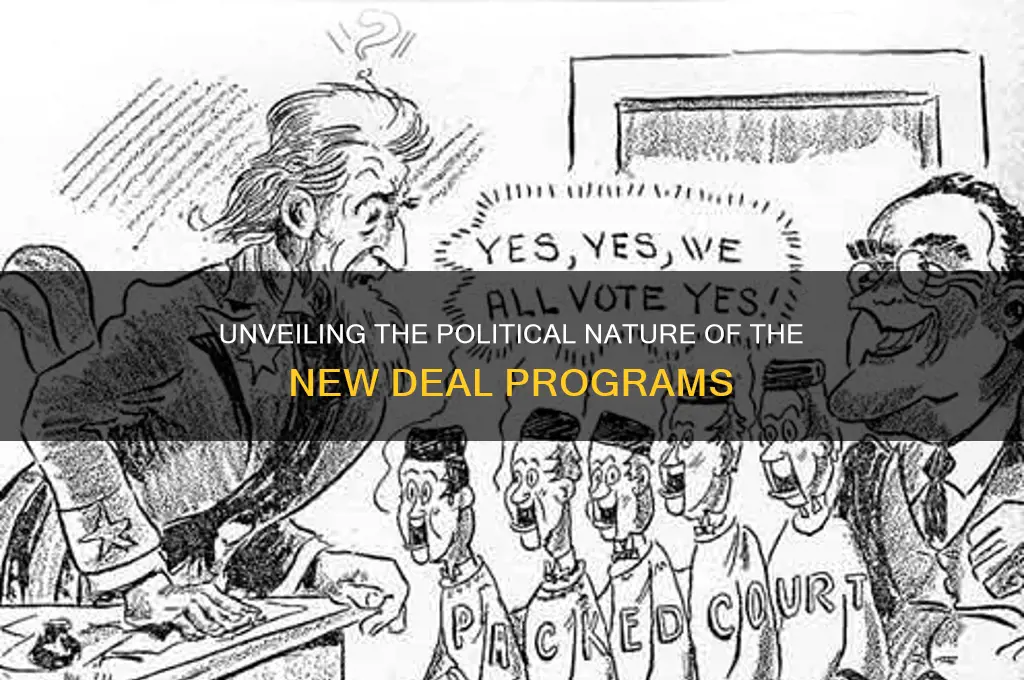

Court Packing Plan: FDR's attempt to reshape the Supreme Court to favor New Deal laws

The Court Packing Plan, officially known as the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, was a bold and controversial initiative by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) to reshape the Supreme Court in favor of his New Deal policies. By the mid-1930s, the Supreme Court had struck down several key New Deal programs, deeming them unconstitutional. Frustrated by the Court’s conservative majority, which often invalidated legislation aimed at economic recovery and social reform, FDR proposed a plan to add up to six new justices to the Court for every sitting justice over the age of 70. This move was explicitly designed to dilute the influence of the existing justices who opposed the New Deal and secure a majority that would uphold his administration’s laws.

FDR’s rationale for the Court Packing Plan was twofold: he argued that the older justices were unable to handle the workload efficiently and that the Court needed to be "balanced" to reflect the will of the people. However, critics saw the plan as a blatant power grab and an assault on the independence of the judiciary. The proposal sparked intense public debate and fierce opposition, even among some Democrats. Many viewed it as an attempt to undermine the system of checks and balances and consolidate presidential authority over the federal government. Despite FDR’s popularity, the Court Packing Plan was widely perceived as politically motivated and undemocratic.

The political fallout from the Court Packing Plan was significant. It marked one of the few instances where FDR faced substantial resistance from his own party and the public. The plan was never implemented, as Congress refused to pass the legislation. However, the political pressure on the Supreme Court had an unintended consequence: the Court began to shift its stance on New Deal laws, upholding several key programs in a series of decisions known as "the switch in time that saved nine." This shift effectively rendered the Court Packing Plan unnecessary, as FDR achieved his goal of judicial support for the New Deal without expanding the Court.

The Court Packing Plan remains a defining example of the political nature of the New Deal. It highlighted the lengths to which FDR was willing to go to ensure the success of his policies, even if it meant challenging the established norms of American governance. While the plan itself failed, it underscored the deep political divisions of the era and the central role of the judiciary in shaping the nation’s response to the Great Depression. It also left a lasting legacy, serving as a cautionary tale about the dangers of politicizing the Supreme Court and the importance of maintaining its independence.

In retrospect, the Court Packing Plan illustrates the inherently political nature of FDR’s New Deal. It was not merely a set of economic reforms but a transformative agenda that required reshaping the federal government’s role in American society. FDR’s willingness to confront the Supreme Court directly demonstrates how deeply political the New Deal was, as it sought to redefine the relationship between the government, the economy, and the people. The episode also reflects the broader tensions between executive power and judicial review, which continue to resonate in American political discourse today.

Are Political Parties Just Nominal? Exploring Their Real Influence and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Labor Unions' Rise: New Deal policies empowering unions and their political influence

The New Deal era marked a significant turning point for labor unions in the United States, as policies implemented under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration directly empowered workers and amplified the political influence of unions. One of the most pivotal pieces of legislation was the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act. This law guaranteed workers the right to form unions, engage in collective bargaining, and participate in concerted activities without fear of retaliation from employers. By establishing the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to enforce these rights, the NLRA provided a federal framework that legitimized and protected union activity, fostering a rapid rise in union membership and power.

Another critical New Deal policy that bolstered labor unions was the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, which included Section 7(a), granting workers the right to organize and bargain collectively. Although the NIRA was later declared unconstitutional, it laid the groundwork for the NLRA and signaled the federal government’s commitment to supporting labor rights. This shift in policy not only strengthened unions but also aligned them with the Democratic Party, as workers recognized the New Deal’s role in improving their economic and social conditions. The political alliance between labor unions and the Democratic Party became a defining feature of American politics in the mid-20th century.

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 further solidified the New Deal’s pro-labor stance by establishing minimum wage, overtime pay, and child labor protections. While not directly focused on unionization, the FLSA improved working conditions and wages, creating a more favorable environment for unions to organize workers. By addressing economic injustices, the FLSA indirectly strengthened labor’s bargaining position and reinforced the political influence of unions as advocates for worker rights.

The New Deal’s emphasis on economic recovery and social justice also led to the creation of public works programs, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which employed millions of workers. These programs often included unionized labor, providing unions with a platform to demonstrate their value in securing better wages and conditions. Additionally, the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill, though not passed during the New Deal, reflected the era’s pro-labor sentiment by proposing national health insurance, a cause later championed by unions.

The political influence of labor unions grew exponentially as they became key allies in promoting and sustaining New Deal policies. Unions mobilized their members to support Democratic candidates and lobbied for legislation that benefited workers. This symbiotic relationship between the Democratic Party and labor unions was instrumental in shaping the modern American welfare state. By empowering unions, the New Deal not only transformed the labor movement but also redefined the political landscape, making labor a powerful force in American politics for decades to come.

Are Political Party Donations Considered Charitable Contributions? Exploring the Debate

You may want to see also

Southern Democrats' Shift: The New Deal's impact on the Solid South's political alignment

The New Deal, implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in response to the Great Depression, had profound political ramifications, particularly in the Solid South. Historically, the South was a stronghold of the Democratic Party, rooted in post-Civil War Reconstruction and the party’s opposition to Republican-led Reconstruction policies. However, the New Deal’s expansive federal programs and labor reforms began to shift this alignment. Southern Democrats, who had long prioritized states' rights and a limited federal government, found themselves at odds with the New Deal’s centralizing tendencies. Despite this ideological tension, many Southern Democrats initially supported the New Deal due to its economic relief measures, which provided critical aid to the impoverished South.

The New Deal’s political impact on the Solid South was twofold. On one hand, it solidified the Democratic Party’s hold on the region in the short term, as Southern voters benefited from programs like the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), and Social Security. These initiatives brought economic relief to a region devastated by the Depression, fostering loyalty to Roosevelt and the Democratic Party. On the other hand, the New Deal’s progressive labor reforms, such as the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act), alienated Southern elites and conservatives, who viewed these policies as threats to their economic and racial hierarchies. This internal divide within the Democratic Party laid the groundwork for future political realignments.

The New Deal also exacerbated racial tensions within the Democratic Party in the South. While African Americans began to shift their allegiance from the Republican Party to the Democrats due to Roosevelt’s policies, Southern Democrats resisted efforts to address racial inequality. The New Deal’s benefits were often unequally distributed in the South, with African Americans frequently excluded from programs like the AAA and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This disparity highlighted the contradictions within the Democratic coalition, as Northern liberals pushed for greater inclusivity while Southern conservatives sought to maintain the status quo. The New Deal thus became a source of friction within the party, foreshadowing the eventual fracture of the Solid South.

The long-term political realignment of the South can be traced to the New Deal’s legacy. As the national Democratic Party increasingly embraced civil rights and federal intervention in the mid-20th century, Southern Democrats grew more alienated. The New Deal had introduced the South to the benefits of federal activism, but it also sowed the seeds of dissent among those who opposed its progressive elements. This tension culminated in the 1960s, when the Democratic Party’s support for civil rights legislation, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, drove many Southern conservatives to the Republican Party. The New Deal, therefore, played a pivotal role in the eventual erosion of the Solid South’s Democratic dominance.

In conclusion, the New Deal’s political impact on the Solid South was complex and transformative. While it initially strengthened the Democratic Party’s hold on the region by providing economic relief, it also introduced ideological divisions that would later reshape Southern politics. The New Deal’s progressive policies and racial dynamics created tensions within the Democratic coalition, setting the stage for the South’s eventual shift toward the Republican Party. Thus, the New Deal was not only an economic program but also a political catalyst that redefined the Solid South’s alignment in American politics.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Core Objectives and Societal Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The New Deal refers to a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s to combat the Great Depression. It is considered political because it represented a significant shift in the role of the federal government in the economy and society, sparking debates between proponents of government intervention and those favoring limited government.

Programs like the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) were highly controversial. The NRA was criticized for overregulating businesses, while the AAA faced opposition for paying farmers to destroy crops and livestock during widespread hunger. These programs highlighted the political divide between those who supported bold government action and those who viewed it as overreach.

The New Deal reshaped American politics by solidifying the Democratic Party's dominance for decades and expanding the federal government's role in social welfare. It also led to the creation of a liberal coalition, including labor unions, ethnic minorities, and Southern whites, while pushing the Republican Party to redefine its stance on government intervention. Its legacy continues to influence debates over economic policy and the role of government.