The classification of political parties within a measurement framework is a nuanced topic that intersects with political science, statistics, and sociology. Political parties can be analyzed using different levels of measurement, each offering unique insights into their characteristics and behaviors. The nominal level identifies parties by name or category without implying order, such as labeling them as Democratic, Republican, or Green. The ordinal level ranks parties based on attributes like ideological positioning (e.g., left, center, right) but does not quantify the exact differences between them. The interval level allows for meaningful comparisons of distances between party positions, often using scales like policy indices, though it lacks a true zero point. The ratio level, rarely applicable here, would require a measurable quantity with a true zero, such as the number of members or financial resources, though even these metrics may not fully capture the complexity of political parties. Understanding which level of measurement to use depends on the research question and the nature of the data being analyzed.

Explore related products

$29.02 $36.99

$49.95 $54.99

What You'll Learn

- Nominal Measurement: Categorizes political parties by name or label without ranking or order

- Ordinal Measurement: Ranks parties based on ideology or policy positions hierarchically

- Interval Measurement: Measures party differences with equal intervals, no true zero

- Ratio Measurement: Compares parties with absolute zero, e.g., membership size

- Practical Applications: Choosing measurement levels for political party analysis in research

Nominal Measurement: Categorizes political parties by name or label without ranking or order

Political parties are often classified using nominal measurement, a fundamental level of measurement in statistics. This approach simply assigns parties to distinct categories based on their names or labels, such as Democratic, Republican, Libertarian, or Green. Unlike higher levels of measurement, nominal measurement does not imply any inherent order, ranking, or quantitative difference between these categories. For instance, listing parties as "Democratic," "Republican," and "Independent" merely distinguishes them as separate entities without suggesting that one is greater, lesser, or more significant than another.

Consider the practical application of nominal measurement in political surveys. Researchers might ask respondents to identify their party affiliation by selecting from a list of options. The data collected—whether someone identifies as a Democrat, Republican, or another label—is purely categorical. This method is straightforward and avoids the complexity of assigning numerical values or hierarchical positions to parties. However, it also limits the depth of analysis, as it cannot reveal relationships or patterns beyond basic categorization.

One key advantage of nominal measurement is its simplicity and clarity. It allows for easy data collection and organization, making it ideal for initial stages of research or broad demographic studies. For example, a pollster might use nominal measurement to quickly gauge the distribution of party affiliations in a given population. The results would show how many individuals identify with each party but would not provide insights into the intensity of their affiliations or the relative strength of each party’s support.

Despite its utility, nominal measurement has limitations. It cannot address questions that require comparison or prioritization. For instance, it cannot determine whether one party is more influential than another or how parties relate to each other ideologically. To explore such questions, researchers would need to employ higher levels of measurement, such as ordinal or interval scales, which introduce ranking or quantitative differences.

In summary, nominal measurement serves as a foundational tool for categorizing political parties by name or label without implying order or hierarchy. Its simplicity makes it effective for basic classification tasks, but its lack of depth restricts its use in more complex analyses. Understanding this level of measurement is essential for anyone seeking to study political affiliations systematically, as it provides a clear starting point for further exploration.

Unveiling Lambeth's Political Cult: Power, Influence, and Hidden Agendas

You may want to see also

Ordinal Measurement: Ranks parties based on ideology or policy positions hierarchically

Ordinal measurement offers a structured approach to understanding political parties by ranking them hierarchically based on ideology or policy positions. Unlike nominal measurement, which simply labels parties without order, ordinal measurement provides a clear sense of relative position. For instance, parties might be ranked as "far-left," "left," "center," "right," or "far-right," creating a spectrum that reflects their ideological alignment. This method allows for comparisons but does not quantify the distance between ranks, making it a qualitative yet ordered system.

To implement ordinal measurement effectively, start by defining clear criteria for ranking. For example, use policy stances on key issues like taxation, healthcare, or climate change to place parties along a continuum. Tools such as political compasses or ideological scales can aid in this process. However, be cautious: ordinal measurement assumes equal intervals between ranks, which may not accurately reflect the nuanced differences between parties. For instance, the gap between "left" and "center" might be smaller than that between "center" and "right," depending on the political context.

A practical application of ordinal measurement is in voter education. By presenting parties in a ranked order, voters can quickly identify where each party stands relative to their own beliefs. For example, a voter who identifies as "center-left" can easily see which parties align most closely with their views. This approach simplifies complex political landscapes, making it particularly useful for elections with numerous parties or candidates. However, it’s essential to update rankings regularly, as parties may shift their positions over time.

One limitation of ordinal measurement is its inability to capture the multidimensional nature of political ideologies. Parties may rank similarly on economic issues but differ drastically on social ones. To address this, consider using multiple ordinal scales—one for economic policies, another for social policies, and so on. This layered approach provides a more comprehensive view while maintaining the hierarchical structure. For instance, a party might rank "left" on economic issues but "center" on social issues, offering a nuanced profile.

In conclusion, ordinal measurement serves as a valuable tool for ranking political parties based on ideology or policy positions. Its hierarchical structure provides clarity and comparability, making it ideal for voter education and political analysis. However, its limitations, such as the assumption of equal intervals and the challenge of multidimensional ideologies, require careful consideration. By combining ordinal measurement with complementary methods and regularly updating rankings, analysts can create a more accurate and dynamic representation of the political landscape.

Joining Pakistan's Political Parties: A Step-by-Step Membership Guide

You may want to see also

Interval Measurement: Measures party differences with equal intervals, no true zero

Political parties, like any complex entities, require precise measurement to understand their differences and similarities. Interval measurement offers a unique lens for this task, quantifying party distinctions with equal intervals but lacking a true zero point. This approach is particularly useful when comparing parties on scales like ideological positioning or policy alignment, where the distance between values is consistent but the absence of a zero doesn’t imply a complete absence of the trait. For instance, if Party A scores 50 and Party B scores 70 on an ideological scale, the 20-point difference signifies a meaningful gap, but neither score suggests a lack of ideology.

To apply interval measurement effectively, consider the following steps. First, define the scale’s parameters, ensuring equal intervals between values. For example, a 100-point scale could measure party stances on economic policy, with each 10-point increment representing a distinct shift in approach. Second, collect data through surveys, voting records, or policy analyses to assign scores to each party. Third, analyze the differences between scores, focusing on the magnitude and direction of gaps rather than absolute values. Caution: avoid interpreting scores as ratios or assuming a zero score equates to neutrality, as interval scales lack this property.

A practical example illustrates its utility. Suppose researchers measure the environmental policies of three parties on a 0–100 scale, where 0 is not a true absence of policy but simply the scale’s starting point. Party X scores 40, Party Y scores 60, and Party Z scores 80. The 20-point difference between each party indicates consistent intervals of policy divergence, allowing stakeholders to gauge relative positions without misinterpreting the scale’s origin. This method is especially valuable in comparative politics, where nuanced differences matter more than absolute stances.

Despite its strengths, interval measurement has limitations. Without a true zero, it cannot determine the absence of a trait, making it unsuitable for measuring attributes like party size or membership count. Additionally, the equal-interval assumption may oversimplify complex political phenomena, such as the multifaceted nature of ideology. To mitigate these issues, pair interval scales with qualitative analysis or supplementary metrics. For instance, combine ideological scores with case studies to provide context for the numerical differences.

In conclusion, interval measurement serves as a powerful tool for quantifying political party differences with precision and consistency. By focusing on equal intervals and avoiding the pitfalls of misinterpreted zeros, researchers and analysts can gain actionable insights into party dynamics. Whether assessing policy alignment or ideological positioning, this approach offers a structured yet flexible framework for understanding the political landscape. Use it thoughtfully, acknowledging its constraints, and it will enhance your ability to measure and compare parties effectively.

Progressive Insurance's Political Ties: Uncovering Their Party Affiliations and Support

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ratio Measurement: Compares parties with absolute zero, e.g., membership size

Political parties, like any social entity, can be measured and compared using various scales. Among these, ratio measurement stands out for its precision and utility. Unlike ordinal or interval scales, ratio measurement allows for meaningful comparisons based on an absolute zero point. For political parties, this often translates to metrics like membership size, where zero genuinely means the absence of members. This scale not only quantifies but also contextualizes the scale and scope of a party’s influence, making it a powerful tool for analysts and strategists alike.

Consider the practical application of ratio measurement in assessing party strength. For instance, if Party A has 100,000 members and Party B has 50,000, the ratio scale tells us that Party A is twice as large. This isn’t just a relative comparison—it’s a statement rooted in an absolute baseline. Such clarity is invaluable when evaluating resource allocation, campaign strategies, or even predicting electoral outcomes. However, relying solely on membership size can be misleading if not paired with other metrics, such as member engagement or demographic diversity.

To effectively use ratio measurement, follow these steps: first, identify the metric tied to an absolute zero (e.g., membership size, campaign funds raised). Second, collect accurate, verifiable data from reliable sources, such as party records or independent audits. Third, calculate ratios or percentages to draw comparisons. For example, if Party C has 20,000 members and Party D has 10,000, the ratio of 2:1 highlights a clear disparity. Caution: avoid conflating size with effectiveness. A smaller party with highly engaged members might outperform a larger, less active one.

A persuasive argument for ratio measurement lies in its ability to debunk myths about party dominance. For instance, a party often perceived as "small" might, in fact, have a membership size comparable to larger parties when measured against an absolute zero. This challenges assumptions and forces a more nuanced understanding of political landscapes. However, critics argue that focusing on size alone ignores qualitative factors like ideology or leadership, which are harder to quantify but equally important.

In conclusion, ratio measurement offers a robust framework for comparing political parties, particularly when grounded in metrics like membership size. Its strength lies in its absolute zero, enabling clear, objective comparisons. Yet, its limitations remind us that no single measure can capture the complexity of political organizations. By integrating ratio measurement with other analytical tools, we gain a more holistic view of party dynamics, informing smarter decisions and strategies.

Scott Griggs' Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Membership

You may want to see also

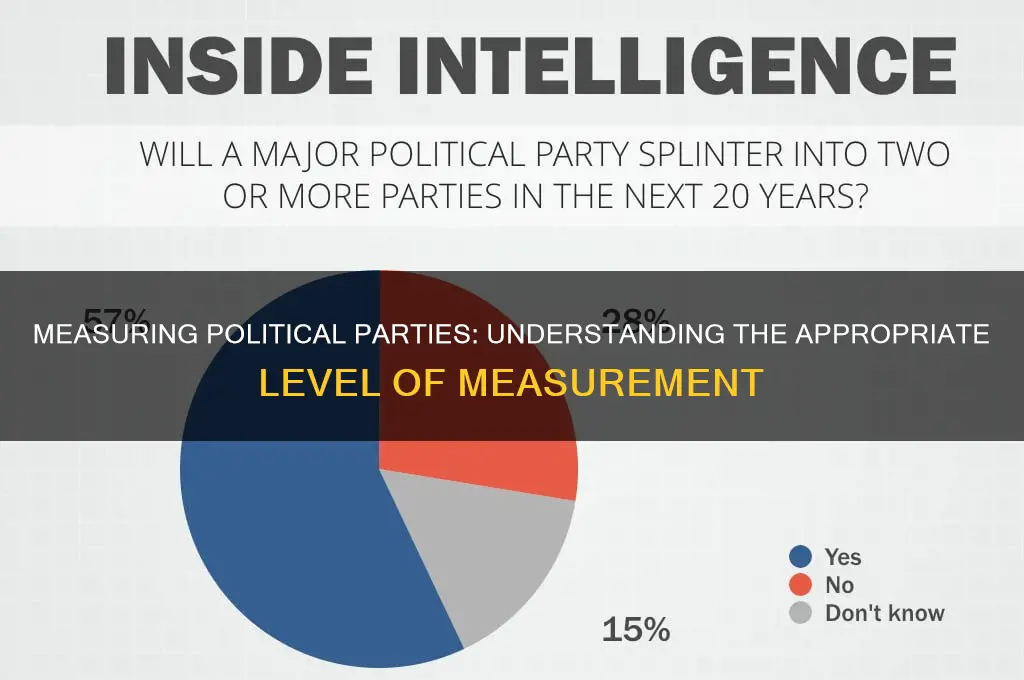

Practical Applications: Choosing measurement levels for political party analysis in research

Political parties, as complex social constructs, defy simple categorization. Their multifaceted nature demands a nuanced approach when selecting measurement levels for research. A one-size-fits-all approach risks oversimplification, leading to flawed conclusions.

The nominal level, identifying parties by name or label, serves as a foundational starting point. It allows for basic categorization and frequency analysis, revealing party distribution within a system. However, it fails to capture the richness of ideological differences or policy stances.

Moving beyond labels, the ordinal level introduces a hierarchy. Researchers can rank parties based on ideological spectra (left-right, liberal-conservative) or specific policy positions. This provides a more nuanced understanding of party positioning, allowing for comparisons like "Party A is more conservative than Party B." Yet, ordinal scales remain limited, as they don't quantify the magnitude of differences between ranks.

For a more precise analysis, interval or ratio levels become essential. These levels allow for meaningful calculations of distances between parties. Researchers can utilize survey data on policy preferences, assigning numerical values to positions and calculating the ideological distance between parties. This enables sophisticated analyses like clustering parties into ideological blocs or tracking shifts in party positions over time.

Media's Influence: Shaping Political Parties and Public Perception

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties are typically measured using the nominal level of measurement, as they represent categories or labels without any inherent order or ranking.

No, political parties cannot be measured on an ordinal scale because there is no inherent hierarchy or ranking among them; they are simply distinct categories.

Political parties are not measured on ratio or interval scales because there is no numerical value, equal intervals, or true zero point associated with their categorization.

The nominal level applies to political parties by classifying them into distinct groups (e.g., Democratic, Republican, Independent) without implying any order or quantitative difference.

In rare cases, political parties might be analyzed using ordinal scales if they are ranked based on external criteria (e.g., popularity or ideological position), but this is not standard practice.