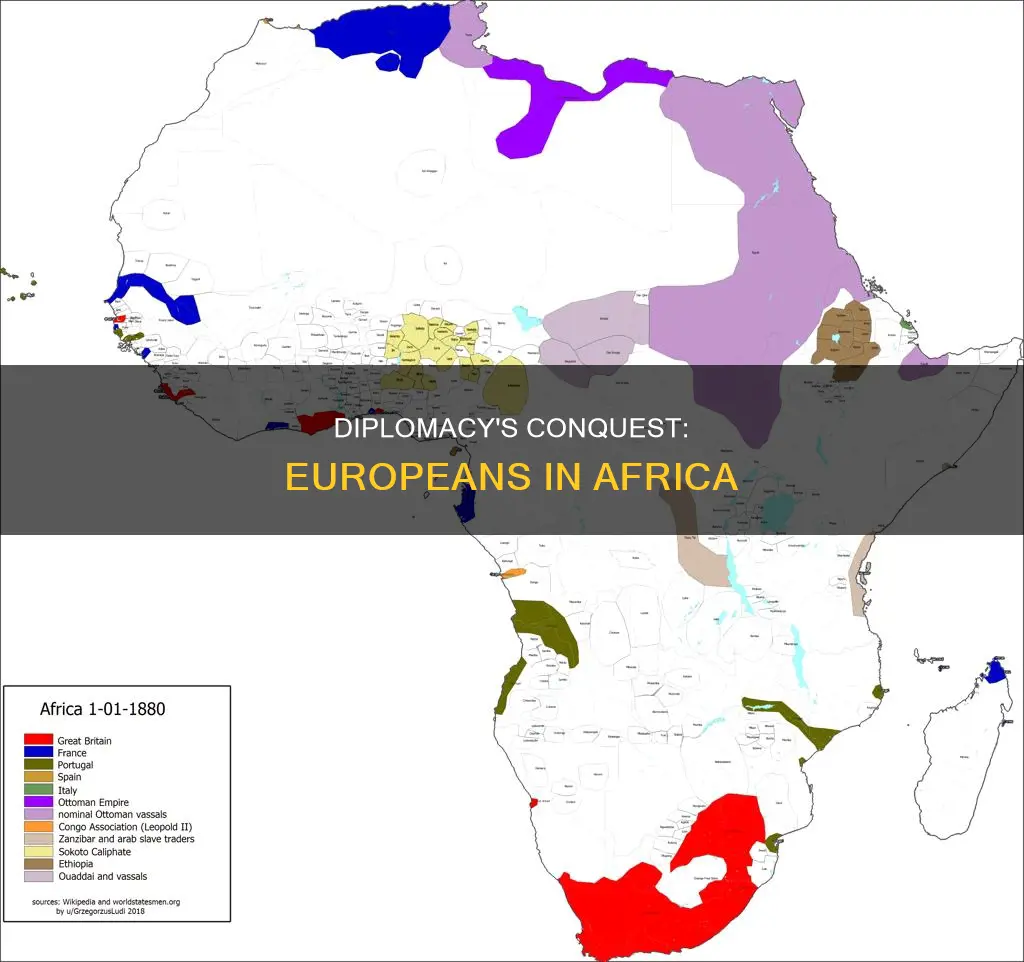

The colonisation of Africa by European powers was driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of New Imperialism. By 1914, almost 90% of the African continent was under European control, with only a few states retaining sovereignty. This period, known as the Scramble for Africa, saw seven Western European powers—Belgium, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Portugal, and Spain—invade, conquer, and colonise most of Africa. While military force, advanced weaponry, and transportation improvements played a significant role in the conquest, diplomatic strategies were also employed by the Europeans. France, for example, captured the fortress of Algiers in 1830 and gradually established control over Algeria through frequent revolts and diplomatic and financial manoeuvres in Tunisia and Egypt. Similarly, Italy's involvement in the debt crisis in Tunisia led to the installation of debt commissioners and looser ties with Turkey. Germany, initially reluctant to colonise, used private companies to establish small colonial operations in Africa, and its world policy aimed to transform the nation into a global power through aggressive diplomacy. The Berlin Conference of 1884-85, which no African sovereigns or representatives were invited to, set the rules for European colonisation in Africa and reduced the risk of conflict between colonial powers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| European countries involved | Belgium, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Portugal, and Spain |

| Time period | Late 19th century and early 20th century |

| Percentage of Africa under European control by 1914 | 90% |

| Driving forces | Second Industrial Revolution, political rivalries, economic and strategic gains, market growth, nationalism, militarism, civilizing mission, and raw materials |

| Methods | Diplomacy, propaganda, financial maneuvers, loans, debt installation, superior weaponry, railroad construction, steamships |

| Resistance | Abushiri revolt, Maji Maji Rebellion, Herero and Namaqua Genocide, international protest against King Leopold II |

| Decolonization | Started after World War II, with 3 dozen new states in Asia and Africa achieving independence by 1960, and most of the continent by 1980 |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Scramble for Africa

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85 is seen as emblematic of the Scramble for Africa. The conference, sponsored by Bismarck, set the rules for European control of African territories and reduced the risk of conflict between colonial powers. No African sovereigns or representatives were invited to the conference, which resulted in a sudden explosion of European imperial claims on the continent. King Leopold II of Belgium is often considered the instigator of the competitive multinational enterprise, as he sought to secure control of the Congo River and its surrounding territories.

During this period, various colonial lobbies emerged to legitimise the Scramble for Africa and other overseas colonial endeavours. In Germany, France, and Britain, the middle class often supported strong overseas policies to ensure market growth. Colonialist propaganda played on popular jingoism and nationalism, and the civilising mission (mission civilisatrice) was a hallmark of the French colonial project. This principle held that it was Europe's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples, leading to a policy of Franco-Europeanisation in French colonies.

Roosevelt's Big Stick Diplomacy: A Forceful Foreign Policy

You may want to see also

The role of Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck was a dominant figure in European history from 1871 to 1890, particularly in the context of the Scramble for Africa. Initially, Bismarck was not in favour of colonies, but he eventually gave in to pressure from both the public and elite circles in the 1880s.

Bismarck was a master of diplomacy, and his aggressive, ruthless approach to foreign affairs allowed him to maintain Germany's position in Europe and expand its influence in Africa. Bismarck's diplomatic skills were instrumental in restructuring the European balance of power, with the creation of the German Empire as the dominant force on the continent, alongside Russia.

In 1884, Bismarck convened the Berlin Conference, which set the rules for European colonial powers to effectively control African territories while reducing the risk of conflict between them. The conference also aimed to end the remaining slave trade and define the scope of missionary activities. However, the primary concern was to prevent war between the European powers as they divided the African continent among themselves. Bismarck's role in the Berlin Conference was a significant diplomatic move that laid down the rules of competition for seeking colonies and established guidelines for European colonisation and trade in Africa.

Bismarck's foreign policies were cautious and pragmatic, allowing Germany to maintain peaceful relations with most European nations, except France, which became one of Germany's bitterest enemies due to the Franco-Prussian War. Bismarck's diplomatic achievements were later undone by Kaiser Wilhelm II, whose policies united other European powers against Germany, leading up to World War I.

Campaign Training: Strategies for Success

You may want to see also

The French civilizing mission

The idea of the civilizing mission was that it was Europe's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples. This ideology required framing Africans as subjects, not citizens, with duties but few rights. The republican ideals of freedom, social equality, and liberal justice were reserved for citizens only. French ideas of civilisation were simultaneously republican, racist, and modern. For example, French colonial officials attacked "'feudal' African institutions such as aristocratic rule and slavery, referring back to France's own experience of revolutionary change.

In the first period, from 1850 to 1898, French policies focused mainly on containing the Sufi Brotherhood. In the second period, from 1898 to 1912, policies shifted to a focus on the conspiratorial roles of the Sufi Brotherhood and fears of Islam, with Islam being presented as a conquering ideology in North Africa. After World War I, there was a new respect for "feudal" chiefs, who were reinstated as a means of control. This discovery of an African "tradition" reinforced a reassertion of traditional values in France.

Roosevelt's New Diplomacy: A Progressive Vision for Foreign Affairs

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.24 $34.99

$58.99 $69.99

The Herero and Namaqua Genocide

In the 19th century, Namibia was populated by several ethnic groups, including the San, Damara, Ovambo, Nama, and Herero. The Nama and Herero were the country's two main tribes, with the Herero being a pastoral people whose way of life centred on their cattle. In 1884, Germany invaded Namibian territory and established the colony of German South West Africa. The discovery of diamonds in 1894 further increased the colonizers' interest in the region. A policy of systematic land confiscation and the influx of German settlers forced the native farmers off their land.

On January 12, 1904, the Herero, led by Chief Samuel Maharero, rebelled against German colonial rule. They attacked a German garrison at Okahandja, killing more than 100 German settlers. In June 1904, German General Lothar von Trotha was sent to Namibia to suppress the revolt. By August 1904, von Trotha had defeated the Herero in the Battle of Waterberg and drove them into the Omaheke desert, where most died of dehydration. The Nama people also rebelled in October 1904 and suffered a similar fate, with many being subjected to imprisonment, forced labour, and medical experiments in concentration camps.

The exact number of casualties is unknown, but it is estimated that between 24,000 and 100,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama were killed. This represented over 80% of the Herero population and 50% of the Nama population in Namibia. In addition to the mass killings, the German soldiers also committed acts of sexual violence against thousands of women, and Dr. Eugene Fischer conducted medical experiments on children born from these rapes, inspiring racist theories that influenced Nazi doctors in the 1930s.

In 2004, the German government acknowledged its responsibility for the genocide and expressed regret, but stopped short of providing financial compensation to the victims' descendants. In 2018, Germany returned the remains of some victims to Namibia but has not yet issued a formal apology.

Where Does Political Campaign Money Go?

You may want to see also

Post-colonialism

- Guinea-Bissau (1974)

- Mozambique (1975)

- Angola (1975)

- Djibouti (1977)

- Zimbabwe (1980)

- Namibia (1990)

The end of colonialism in Africa was met with jubilation, with the hope that it would lead to socioeconomic emancipation after decades of segregation, discrimination, and denial of local values and traditions. However, the post-colonial reality has been marked by corruption, conflict, the rise of violent non-state actors, elitism, poverty, and inequality. This has led to a new scramble for Africa, with major powers competing for influence on the continent.

Post-colonial Africa has been characterized by the challenges of consolidating inclusive development and ensuring a smooth socioeconomic and political transition. There has been pressure on post-colonial African leaders to develop policies that recognize the continent's diverse culture, language, and traditions while also addressing the needs of the people. This has proven difficult, as the post-independent African state has often been overbearing and associated with a small group of individuals aligned with the individual in power.

Nationalist movements arose across West Africa following World War II, most notably in Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah, which became the first sub-Saharan colony to achieve independence in 1957. By 1974, West Africa's nations were entirely autonomous, but many have since been plagued by corruption and instability, with notable civil wars and military coups.

Apartheid in South Africa, which began in 1948, was a continuation of existing policies of racial segregation and economic exploitation of the African majority. It was characterized by clashes of culture, violent territorial disputes, dispossession, and repression. Apartheid ended in 1994, and Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress was elected president in the country's first non-racial election.

Campaign Trail Chaos: "Ahhhh!" and Political Passion

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Belgium, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Portugal, and Spain all took part in the Scramble for Africa.

Advances in weaponry, rapid railroad construction, and the introduction of steamships all contributed to the success of the conquering nations. In addition, the European powers often portrayed the native Africans as "uncivilised" and used this as a justification for their colonial exploits.

By 1914, almost 90% of the African continent was under European control. The remaining sovereign states included Liberia, Ethiopia, and the Dervish State. The Scramble for Africa resulted in the arbitrary division of ethnic and linguistic groups and the drawing of new natural boundaries. This had a profound impact on the political complexity of the region.

Between 1945 and 1960, three dozen new states in Asia and Africa achieved autonomy or outright independence. This process of decolonisation was influenced by growing independence movements, indigenous political parties, and trade unions, as well as pressure from within the imperialist powers and external forces such as the United States and the Soviet Union.