The Anti-Defection Law, also known as the 52nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution, was passed in 1985 to limit the ability of politicians to switch parties in parliament. The Tenth Schedule of the Amendment resulted in the introduction of the word 'political party' in the Constitution of India, giving political parties recognition in the Constitution. The Amendment was passed to prevent elected members from changing parties, which had previously led to political turmoil in the country. The Ninety-first Amendment to the Constitution in 2003 strengthened the Anti-Defection Law by adding provisions for the disqualification of defectors and banning them from holding ministerial posts for a period of time.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Anti-Defection Law, or the 52nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution |

| Year | 1985 |

| Purpose | Limiting the ability of politicians to switch parties in parliament |

| Provisions | Members of Parliament or State Legislatures who switch parties are disqualified |

| Any member who votes or abstains from voting contrary to the directive of their political party is disqualified | |

| Nominated members joining a political party after 6 months are disqualified | |

| Members disqualified due to defection cannot hold ministerial or other remunerative political posts | |

| The number of ministers in states and union territories should not exceed 15% of the total members in the house | |

| Defection arising out of splits is exempted | |

| The law does not apply to Presidential elections |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The 52nd Amendment Act, 1985

Prior to the introduction of this amendment, India witnessed a period of political turmoil due to frequent defections among legislators. Between the 1967 and 1971 general elections, almost 50% of the 4,000 legislators elected to central and federal parliaments subsequently defected, often in pursuit of personal gain and political horse-trading. This led to the toppling of multiple state governments and caused uncertainty in the election of the Prime Minister and Chief Ministers in some states and territories.

The Anti-Defection Law, as enshrined in the 52nd Amendment, also applies to nominated members of Parliament or State Legislatures. These nominated members are subject to disqualification if they join any political party within six months of taking their seat. Additionally, independent members of Parliament or State Legislatures are disqualified if they join a political party after their election.

While the 52nd Amendment Act, 1985, was a crucial step towards combating political defections, it has undergone subsequent amendments to address loopholes. In 2003, the Ninety-first Amendment Act was passed to strengthen the anti-defection provisions. This amendment added penalties for defectors, banning them from holding ministerial posts for a period of time, and addressed the issue of splits versus mergers within political parties.

Texas Constitution: Last Amendment and Its Date

You may want to see also

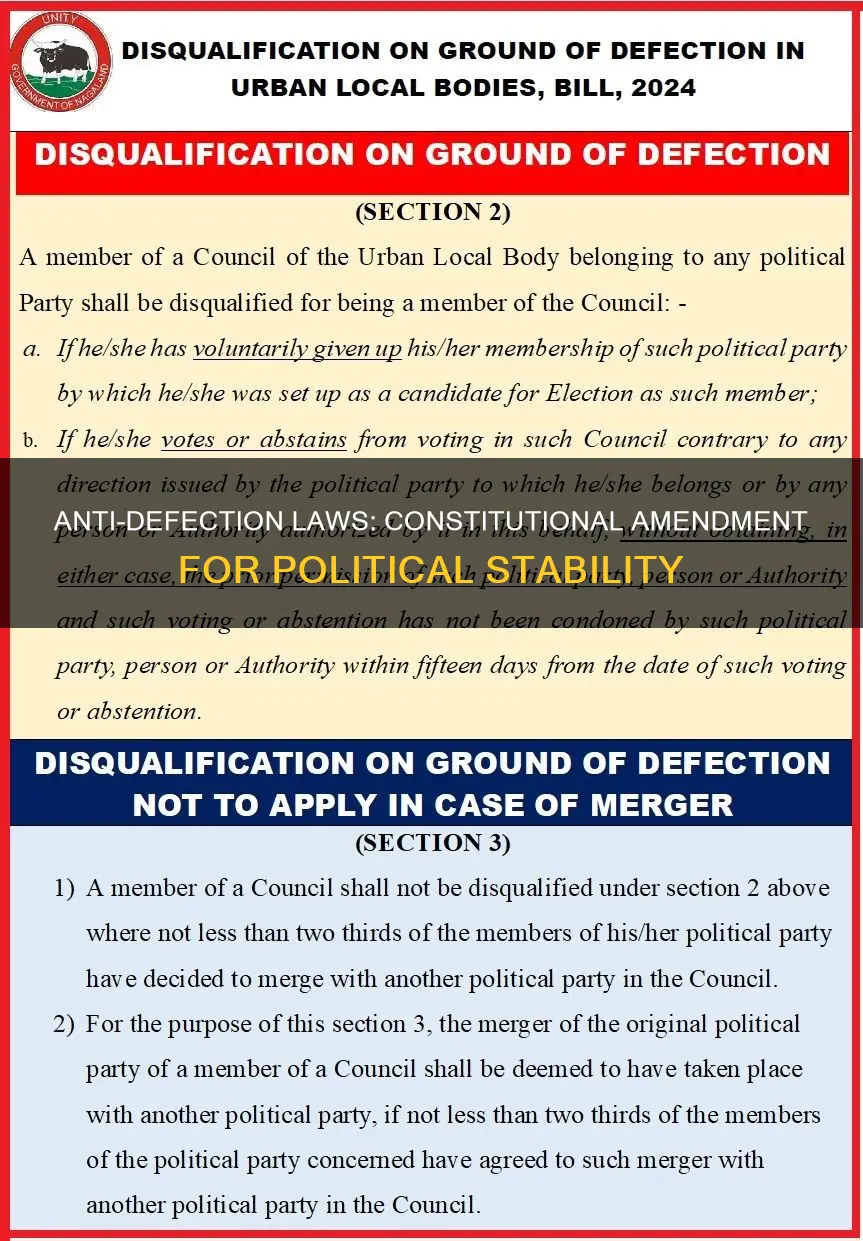

Disqualification on grounds of defection

The Constitution (Fifty-second Amendment) Act, 1985, also known as the Anti-Defection Law, was passed in India to limit the ability of politicians to switch parties in parliament. The law was sought to prevent political defections, which were becoming increasingly common and were feared to undermine the foundations of democracy.

The Anti-Defection Law introduced the word "Political Party" into the Constitution of India, giving political parties recognition in the Constitution. The law applies to both the Parliament and the state assemblies.

The Anti-Defection Law specifies the factors that can lead to a member being disqualified from the Parliament or State Assembly. These include:

- Voluntarily giving up membership of a political party. This does not require a formal resignation and can be inferred from a legislator's conduct, such as criticising the party in public forums or attending rallies of opposition parties.

- Voting or abstaining from voting contrary to the directive circulated by their political party. This includes defying the party whip on any issue, which can result in the loss of membership of the House.

- Joining another political party after being elected as a representative of a certain political party.

- A nominated member joining any political party after six months from the date they take their seat.

Ninety-First Amendment Act, 2003

The Ninety-First Amendment Act, passed in 2003, strengthened the Anti-Defection Law by adding provisions for the disqualification of defectors and banning them from being appointed as ministers for a period of time. This amendment also exempted disqualifications arising out of splits or mergers of political parties, provided that at least one-third to two-thirds of the members agreed to the split or merger.

The decision on disqualification on the grounds of defection lies with the Presiding Officer, who can act based on a petition by any member of the House. This decision is subject to Judicial Review, allowing appeals to be made in the High Court and Supreme Court.

Texas' Constitution: Last Amendments and Future Changes

You may want to see also

The Ninety-First Amendment Act, 2003

Background: The Need for the Ninety-First Amendment

Before the introduction of the Anti-Defection Law, India witnessed a high rate of political defections. In the 1967 and 1971 general elections, nearly 50% of the 4,000 legislators elected to central and federal parliaments subsequently defected, according to one estimate. This led to concerns about the stability of India's democracy and the need to address the issue.

Key Provisions of the Ninety-First Amendment

- Disqualification of Defectors: The amendment added provisions for the disqualification of defectors, preventing them from holding any ministerial or remunerative political post during their term as a member. It specified that a member would be disqualified if they voluntarily gave up their membership in a political party or voted/abstained from voting contrary to their party's directives.

- Ban on Ministerial Appointments: Defectors were banned from being appointed as ministers for a period of time, addressing the issue of elected representatives seeking cabinet positions by changing allegiances.

- Limiting Defections in Splits: The amendment exempted disqualifications arising from splits within a political party, but only if one-third of the members defected. This was to prevent the exploitation of splits to cause divisions in parties.

- Disqualification Exemptions: The amendment provided exemptions from disqualification in the case of mergers of political parties, but only with the consent of two-thirds of the members. It also exempted the Speaker, Chairman, and Deputy-Chairman of various legislative Houses.

- Decision-Making Authority: The Ninety-First Amendment mandated that the Chairman or Speaker of the respective legislative house would be the ultimate authority in deciding on questions of disqualification arising from defection.

Impact and Challenges

Amendments in Ohio's Constitution: Where Are They?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political instability and erosion of trust

Political defection has been a matter of national concern in India, with legislators changing their political allegiance and causing political turmoil in the country. The 52nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution, also known as the Anti-Defection Law, was passed in 1985 to limit the ability of politicians to switch parties in parliament. This amendment introduced the word "political party" into the Constitution, giving them recognition.

The amendment was further strengthened in 2003 with the Ninety-first Amendment, which added provisions for the disqualification of defectors and banned them from holding ministerial positions for a period. This amendment addressed the exploitation of exceptions provided in the original amendment, which allowed for multiple divisions within political parties.

To address this crisis, projects like TRUEDEM (Trust in European Democracies) aim to systematically examine the patterns, mechanisms, and determinants of political trust in Europe. By focusing on the trustworthiness of political actors and institutions, the project seeks to develop a revised theory of political trustworthiness and formulate policy interventions to strengthen the overall trustworthiness of political institutions.

The decline in institutional trust has a significant impact on society. It undermines the social contract and sustainable development, especially in fragile states. To restore trust, institutional reform and global cooperation are necessary, along with effective governance practices that promote economic redistribution.

Amendment Story: 21st Amendment's Addition to the Constitution

You may want to see also

The role of the Speaker

The Indian Constitution's 52nd Amendment, also known as the Anti-Defection Law, was enacted in 1985 to prevent political defections. The law was amended to prevent elected MLAs and MPs from changing parties, as this had previously led to political turmoil in the country.

The Anti-Defection Law does not provide a specific timeframe for the Speaker to decide on defection cases, which has led to prolonged delays and uncertainty, hindering political stability and governance. In some cases, members who had defected from their political parties continued to be House members due to delays in decision-making by the Speaker. The law allows for any person elected as chairman or speaker to resign from their party and rejoin if they demits their post.

There have been proposals to limit the Speaker's role in defection cases and establish an independent Anti-Defection Tribunal composed of non-partisan legal experts. This would address concerns about political influence and the discretionary use of disqualification powers.

The Supreme Court has maintained that Speakers should be the first authority to decide on disqualification, but that their decisions are subject to judicial review. The court held that the Speaker should function as a tribunal, and their decision is subject to review on grounds of malafides and perversity.

Amendment Location: Where Does the 14th Fit?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Anti-Defection Law, or the 52nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution, is a constitutional amendment limiting the ability of politicians to switch parties in parliament. The law was enacted to prevent elected MLAs and MPs from changing parties.

The law was enacted to prevent or discourage defection by imposing penalties on politicians who switch parties or violate party discipline. It aims to ensure that politicians are held accountable to the voters who elected them and to maintain the stability and cohesion of political parties.

The law includes provisions for the disqualification of MPs and MLAs on the grounds of defection. If an elected member voluntarily gives up their membership of a political party or votes/abstains from voting contrary to the party's directives, they can be disqualified. The law also applies to independent members who join a political party after being elected.

Yes, the Ninety-first Amendment to the Indian Constitution in 2003 strengthened the law by adding provisions for the disqualification of defectors and banning them from holding ministerial or other political posts for a period of time. This amendment addressed concerns about political horse-trading and the exploitation of exceptions in the original law.