The Import-Export Clause, also known as Article I, § 10, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, prevents states, without the consent of Congress, from imposing tariffs on imports and exports above what is necessary for their inspection laws. The clause also ensures that revenues from all tariffs on imports and exports go to the federal government. The Tonnage Clause (Art. I, § 10, Clause 3) complements the Import-Export Clause by preventing states from imposing taxes based on the internal capacity of a vessel, which is an indirect way of taxing imports and exports. The interpretation of the Import-Export Clause has been the subject of several Supreme Court cases, with modern legal scholars questioning the interpretation that it only applies to trade with foreign nations and not interstate commerce.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Import-Export Clause |

| Location | Article I, Section 10, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution |

| Purpose | Prevent states from imposing tariffs on imports and exports without the consent of Congress |

| Scope | Applies to foreign trade and interstate commerce |

| Exceptions | Allows states to impose tariffs necessary for executing inspection laws |

| Revenues | All revenues from tariffs on imports and exports go to the federal government |

| Judicial Interpretation | Supreme Court cases have applied and interpreted the clause, with some ambiguity in certain cases |

| Related Clauses | Tonnage Clause, Port Preference Clause, Export Clause |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

- The Import-Export Clause limits state taxation of exports

- The Import-Export Clause is in Article I, Section 10, Clause 2 of the US Constitution

- The Tonnage Clause prevents states from imposing taxes based on vessel capacity

- The Export Clause ensures the national government can raise revenue

- The Port Preference Clause constrains the national government from favouring ports in some states

The Import-Export Clause limits state taxation of exports

The Import-Export Clause, or Article I, § 10, clause 2 of the United States Constitution, prevents states from imposing tariffs on imports and exports without the consent of Congress. The clause is designed to limit the states' ability to interfere with commerce and generally prohibits them from imposing imposts or duties on imports and exports, except for what is necessary for executing inspection laws. This ensures that the revenues from all tariffs on imports and exports go to the federal government.

The Import-Export Clause plays a crucial role in maintaining uniformity in trade relations with foreign countries. Before the Constitution, states acted in their own interests, leading to significant trade disputes and a lack of harmony in trade relations. By giving Congress control over imposts and duties on imports and exports, the clause promotes consistent trade policies and protects the interests of all states.

The interpretation of the Import-Export Clause has been a subject of debate among legal scholars. In 1869, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the clause only applied to imports and exports with foreign nations, excluding trade between states. However, this interpretation has been questioned by modern legal scholars, with some arguing that there is no indication in the Constitution that the clause is limited to foreign goods. For instance, in 1945, the Supreme Court held that the clause applied to imports from the Philippine Islands, which were a US territory at the time.

The Export Clause, a part of the Import-Export Clause, is significant in ensuring the national government's ability to raise revenue. During the Constitutional Convention, delegates recognised that imports and exports were obvious revenue sources, and the Export Clause allows the government to tax both. This provision was particularly important to southern delegates, as taxes on exports could negatively impact their region, known as the "staple States," which was the primary source of exports at the time.

In conclusion, the Import-Export Clause plays a vital role in regulating state taxation of exports and maintaining harmonious trade relations. Its interpretation has evolved over time, and it continues to shape trade policies and revenue generation for the national government.

Jury Trials: Ensuring Fairness and Impartiality

You may want to see also

The Import-Export Clause is in Article I, Section 10, Clause 2 of the US Constitution

The Import-Export Clause, also known as Article I, Section 10, Clause 2 of the US Constitution, plays a pivotal role in shaping trade dynamics across states. This clause stands as a cornerstone of economic policy, curtailing the ability of individual states to levy tariffs on imports and exports without the express consent of Congress. The clause asserts that:

> "No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing its inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Controul of the Congress."

This clause serves as a bulwark against states imposing arbitrary tariffs on goods entering or leaving their borders, fostering a more uniform and predictable trade environment across the nation. It ensures that states cannot unilaterally impose excessive taxes on goods, which could hinder interstate commerce and disrupt the free flow of goods and services.

The Import-Export Clause is underpinned by the recognition that tariffs on imports are a critical source of revenue for the federal government. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 12, advocated for this centralisation of power, arguing that the federal government could more effectively impose and manage tariffs than individual states operating in isolation. This clause, therefore, consolidates the federal government's control over trade policy and revenue streams.

While the Import-Export Clause primarily addresses tariffs and duties levied by states, it also encompasses inspection laws. States are permitted to impose taxes or duties related to the inspection of imports and exports, but only to the extent necessary for executing these inspections. This exception recognises the importance of ensuring the quality and safety of goods entering and leaving a state.

The interpretation and application of the Import-Export Clause have evolved over time, with several nineteenth-century Supreme Court cases applying it to duties and imposts on interstate imports and exports. However, in 1869, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the clause only applied to trade with foreign nations, excluding trade between states. This interpretation, however, has been questioned by modern legal scholars, reflecting the ongoing evolution of constitutional understanding.

Senators' Benefits: What the US Constitution Provides

You may want to see also

The Tonnage Clause prevents states from imposing taxes based on vessel capacity

The Import-Export Clause of the US Constitution is outlined in Article I, Section 10, Clause 2. This clause prevents states from imposing tariffs on imports and exports without the consent of Congress. The Import-Export Clause was designed to limit the states' ability to interfere with commerce and to secure tariff revenues for the federal government.

The Tonnage Clause, or Article I, Section 10, Clause 3, is an extension of the Import-Export Clause. It prevents states from imposing taxes based on the tonnage or internal capacity of a vessel. This was an indirect method of taxing imports and exports, as duties were imposed on ships for entering or lying in a harbour, with charges based on the vessel's capacity.

At the time the Constitution was adopted, various states imposed duties of tonnage, which were distinct from charges for pilotage, loading, and unloading cargo. The Tonnage Clause was intended to prevent states with convenient ports from taxing goods destined for states without good ports. It also aimed to ensure uniformity in duties of tonnage across the United States.

In Clyde Mallory Lines v. Alabama, the Supreme Court clarified that the Tonnage Clause's prohibition on tonnage duties was meant to supplement the Import-Export Clause. The Court explained that the framers of the Constitution wanted to forbid a corresponding tax on the privilege of vessel access to state ports and address doubts about the effectiveness of the Commerce Clause in this regard.

The interpretation and application of the Import-Export Clause have been the subject of several Supreme Court cases, including Brown v. Maryland, which defined the terms "imports" and "imposts", and United States v. IBM, which addressed the Export Clause's prohibition on nondiscriminatory taxes on exports.

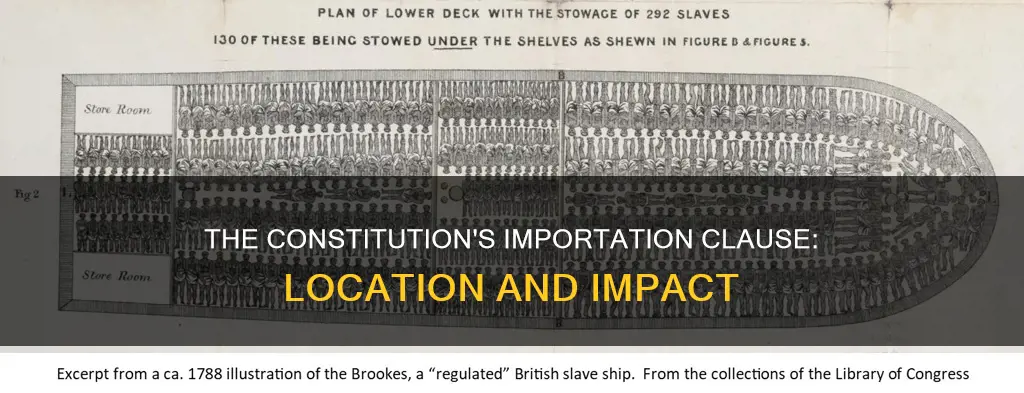

The US Constitution's Slave Count: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Export Clause ensures the national government can raise revenue

The Export Clause, also known as Article I, §9, clause 5, is a provision in the United States Constitution that prohibits the federal government from imposing any "tax or duty ... on articles exported from any state." The clause was proposed by southern states, which feared that northern states would dominate Congress and impose excessive taxes on exports from southern states, disproportionately benefiting the federal government at the expense of the south.

The Export Clause was designed to address concerns about the potential negative impact of export taxes on certain regions, particularly the "'staple states' in the South, from which most exports originated at the time. Delegates such as Alexander Hamilton argued that the government should be able to tax both imports and exports, as they were obvious sources of revenue. However, southern delegates worried that taxes on exports would make agricultural products like cotton more expensive and less attractive, which could indirectly attack slavery.

The Export Clause is interpreted in conjunction with the Import-Export Clause (Article I, § 10, clause 2), which prevents states from imposing tariffs on imports and exports without the consent of Congress. The Import-Export Clause also secures for the federal government the revenues from all tariffs on imports and exports. Together, these clauses were critical to the Constitution's adoption, addressing concerns about favouritism and ensuring the national government's ability to raise revenue.

The Supreme Court has ruled on several occasions regarding the interpretation and application of the Export Clause. For example, in United States v. IBM (1996), the Court held that an excise tax on premiums paid to foreign insurers for insurance on exports was unconstitutional. Additionally, in United States v. United States Shoe Corp. (1998), the Court ruled that a "harbour maintenance tax", measured by cargo value, could not be imposed on vessels engaged in exportation. These cases demonstrate how the Export Clause constrains the national government's taxation powers and ensures that taxation does not favour one part of the country over another.

Voting Shares: Understanding the Quorum Threshold

You may want to see also

The Port Preference Clause constrains the national government from favouring ports in some states

The Import-Export Clause, or Article I, § 10, clause 2 of the United States Constitution, prevents states from imposing tariffs on imports and exports without the consent of Congress. It also ensures that revenues from all tariffs on imports and exports go to the federal government. The primary purpose of this clause was to limit the states' ability to interfere with commerce and prevent them from imposing duties on imports and exports.

The Port Preference Clause, also known as the No Preference Clause, is a part of the Constitution that constrains the national government from favouring the ports in some states over others. This clause was included to address the concern that a strong national government might favour one part of the country over another. The specific concern was raised by the Maryland delegation, who worried that neighbouring states with competing ports, like Virginia, might benefit commercially if the government compelled all ships sailing into or out of the Chesapeake Bay to clear and enter at Norfolk, Virginia. The Port Preference Clause was intended to prevent this kind of favouritism and protect the commercial interests of individual states.

The Supreme Court emphasised in 1886 that the Port Preference Clause applied to Congress and not state legislation. However, the interpretation and application of this clause have been complex, with only a handful of Supreme Court cases interpreting it. One example is United States v. United States Shoe Corp. (1998), where the Court held that a "harbour maintenance tax", measured by cargo value, was indeed a tax and could not be imposed on vessels engaged in exportation.

The Tonnage Clause (Art. I, § 10, clause 3) is another provision that complements the Import-Export Clause by preventing states from imposing taxes based on the tonnage or internal capacity of a vessel, which is an indirect way of taxing imports and exports. This clause was also designed to prevent states with convenient ports from taxing goods destined for states with less favourable port infrastructure.

In conclusion, the Port Preference Clause was included in the Constitution to constrain the national government from favouring ports in some states over others, thereby ensuring commercial fairness and protecting states' commercial interests. The interpretation and application of this clause have been challenging, and it has had limited use in modern legal decisions.

Federalism Fundamentals: Exploring Horizontal Constitutional Provisions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Importation Clause, also known as the Import-Export Clause, is in Article I, Section 10, Clause 2 of the US Constitution.

The Import-Export Clause prevents states, without the consent of Congress, from imposing tariffs on imports and exports above what is necessary for their inspection laws. It also secures for the federal government the revenues from all tariffs on imports and exports.

The Tonnage Clause (Article I, § 10, Clause 3) prevents states from imposing taxes based on the tonnage (internal capacity) of a vessel, which is an indirect method of taxing imports and exports.

The Import-Export Clause was designed to limit the states' ability to interfere with commerce and prevent states with convenient ports from taxing goods destined for states without good ports.

![The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America: The Declaration of Independence ... 1783 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![The Santa Clause 3-Movie Collection [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/712RMUGfHML._AC_UY218_.jpg)