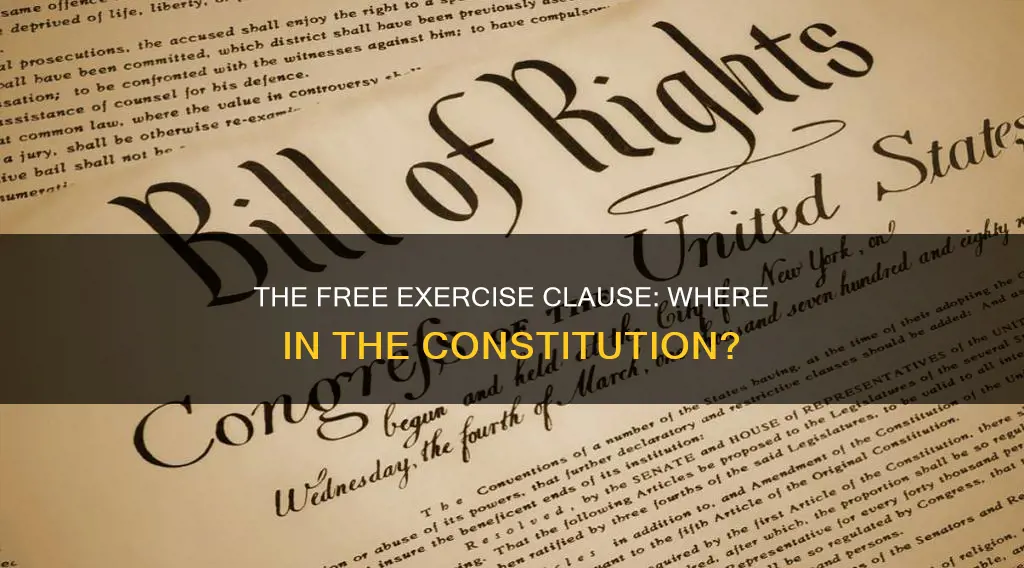

The Free Exercise Clause is part of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. It states that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. The Free Exercise Clause protects citizens' right to practice their religion without government interference, as long as it does not conflict with public morals or a compelling government interest. The Supreme Court first interpreted the Free Exercise Clause in 1878 in the case of Reynolds v. United States, which involved the prosecution of a polygamist under federal law.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Location in the Constitution | The Free Exercise Clause is found in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. |

| Purpose | The Free Exercise Clause protects citizens' right to practice their religion without government interference, as long as it does not conflict with "public morals" or a "compelling" governmental interest. |

| History of Interpretation | The Supreme Court's interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause has evolved over time, from relative neglect to a narrow and then broader view, with periods of inconsistency and shifting interpretations. |

| Case Law | Notable cases include Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), Reynolds v. United States (1878), Sherbert v. Verner, and City of Boerne v. Flores. |

| Relationship with Other Clauses | The Free Exercise Clause is often discussed alongside the Establishment Clause, another provision in the First Amendment concerning religion. |

| Economic Impact | The Free Exercise Clause promotes a free religious market by preventing the taxation of religious activities by minority sects. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause

The Free Exercise Clause is part of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The First Amendment has two provisions concerning religion: the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause. The text of the First Amendment states:

> Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abriding the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The Free Exercise Clause prohibits government interference with religious belief and, within limits, religious practice. It protects the right of individuals to hold, practice, and change beliefs freely according to the dictates of conscience. The Free Exercise Clause does not, however, protect religious practices that are considered crimes. For example, in the 1878 case of Reynolds v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a polygamist, deciding that to do otherwise would provide constitutional protection for a range of religious beliefs, including those as extreme as human sacrifice.

The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from establishing or sponsoring a religion. Historically, this meant prohibiting state-sponsored churches, such as the Church of England. Today, whether government assistance violates the Establishment Clause is often evaluated using the three-part "Lemon" test set forth by the Supreme Court in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). Under this test, government assistance to religion is permitted only if (1) its primary purpose is secular, (2) it neither promotes nor inhibits religion, and (3) there is no excessive entanglement between church and state.

Legal and Constitutional Issues: What Rights Are at Risk?

You may want to see also

Free exercise of religion in schools

The Free Exercise Clause is found in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof". The First Amendment's Free Exercise Clause forbids Congress from prohibiting the free exercise of religion. The clause promotes a free religious market by precluding the taxation of religious activities by minority sects.

The Free Exercise Clause has been the focus of many Supreme Court cases, including several involving Jehovah's Witnesses, which gave the Court the opportunity to rule on the application of the clause. The Court's interpretation of the clause has evolved over time, from a period of little attention to a narrow view of governmental restrictions, then to a broader view in the 1960s, and a subsequent receding. One notable case is Cantwell v. Connecticut in 1940, which held that the Free Exercise Clause is enforceable against state and local governments. This case also established the general framework for the Supreme Court's Free Exercise jurisprudence.

Another significant case is Sherbert v. Verner, where the Court overturned the state Employment Security Commission's decision to deny unemployment benefits to a practicing member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. The Court held that denying benefits because of the appellant's religious faith effectively penalised the free exercise of her constitutional liberties. This case set a precedent for the application of the Free Exercise Clause in situations where laws impose special burdens on religious activities.

The Supreme Court has also addressed the issue of free exercise of religion in schools. In one case, the Court held that prayers in public schools violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, even if they are nondenominational and not tied to any specific religion. Additionally, the Court has clarified that public school officials must show neither favoritism toward nor hostility against religious expression, such as prayer. Schools have the discretion to allow students time for off-premises religious instruction, as long as participation is not encouraged or discouraged, and students are not penalised for their choices.

In conclusion, the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment protects citizens' right to practice their religion, including in schools, as long as it does not interfere with "public morals" or a "compelling" governmental interest. The Supreme Court has played a crucial role in interpreting and applying the clause through various cases, shaping the understanding of religious freedom in the United States.

Slavery's Constitutional Legacy: Three Provisions Examined

You may want to see also

Free exercise of religion in the workplace

The Free Exercise Clause, accompanied by the Establishment Clause, is found in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. It states:

> Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The Free Exercise Clause prohibits government interference in religious belief and, within limits, religious practice. It ensures that no one can be compelled to accept any creed or form of worship, and that federal or state legislation cannot make it a crime to hold any religious belief or opinion.

The First Amendment does not apply to private workplaces. However, federal law requires agencies to accommodate employees' religious expression and exercise, unless such accommodation would impose an undue hardship on the agency's operations. This includes allowing employees to engage in private religious expression in their personal work areas, not regularly open to the public, to the same extent that they may engage in non-religious private expressions. Agencies may regulate the time, place, and manner of all employee speech, provided it does not discriminate based on content or viewpoint.

Employees are protected from religious discrimination, harassment, and coercion in the workplace. This includes discriminatory intimidation, severe or pervasive religious ridicule or insult, and being forced to participate or refrain from religious activities as a condition of employment.

There have been several court cases that have helped define the boundaries of religious freedom in the workplace. For example, in Sherbert v. Verner, the Supreme Court overturned a decision to deny unemployment benefits to a practicing member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church who was forced out of her job due to her inability to work on Saturdays, which was against her religious beliefs. In Groff v. DeJoy, the court tightened the standard by which employers must prove an "undue hardship" for granting religious accommodation.

The Executive: Directly Elected Under the Original Constitution?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Free exercise of religion in prisons

The Free Exercise Clause is part of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. It states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof". The clause prohibits government interference with religious belief and, within limits, religious practice.

The Supreme Court first interpreted the Free Exercise Clause in 1878 in Reynolds v. United States, which concerned the prosecution of a polygamist under federal law. The defendant claimed protection under the Free Exercise Clause, but the Court upheld the law and the government's prosecution, stating that the clause protects religious practices but does not protect criminal practices. This set a precedent for the Court's interpretation of the clause over the next century, which took on a relatively narrow view of the governmental restrictions required.

In Cantwell v. Connecticut in 1940, the Supreme Court held that the Free Exercise Clause is enforceable against state and local governments, establishing the general framework for the Court's Free Exercise jurisprudence. The case also gave the Court the opportunity to apply the clause to the states. In the mid-20th century, several cases involving Jehovah's Witnesses allowed the Court to rule on the application of the clause.

In the 1960s, the Court's interpretation of the clause grew into a much broader view, with Sherbert v. Verner setting a new standard of "strict scrutiny". The Court overturned the state's decision to deny unemployment benefits to a practicing member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church who was forced out of her job due to her religious beliefs. Justice William Brennan stated that "to condition the availability of benefits upon this appellant's willingness to violate a cardinal principle of her religious faith effectively penalizes the free exercise of her constitutional liberties."

Despite these protections, jails and prisons throughout the country frequently violate the religious rights of prisoners. The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) guarantees incarcerated individuals the right to the free exercise of their religious beliefs while behind bars. However, this has not prevented instances of religious freedom violations, such as the case of Damon Landor, a practicing Rastafarian who had his dreadlocks shaved against his will upon arriving at a correctional facility in Louisiana.

Prisoners have the right to sue prison officials who infringe upon their religious freedom under the Civil Rights Act of 1871, and the New York Correction Law also gives prisoners the right to free exercise of religion, subject to the disciplinary needs of the prison. Courts will generally balance the importance of a religious practice with prison needs, allowing interference only if a practice causes substantial problems and if no other less restrictive means exist to achieve the same end.

The Constitution: Godless or God-Given?

You may want to see also

Free exercise of religion and taxation

The Free Exercise Clause is part of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof". This clause prohibits the US government from restricting the free exercise of religion, establishing a national religion, or favouring one religion over another.

The Free Exercise Clause has been interpreted by the Supreme Court in various cases throughout history, with one of the earliest interpretations occurring in 1878 in Reynolds v. United States. In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of Reynolds for bigamy, arguing that otherwise, a range of religious beliefs, including those as extreme as human sacrifice, would be constitutionally protected. The Court affirmed that while laws cannot interfere with religious beliefs and opinions, they may interfere with practices.

The Supreme Court has also interpreted the Free Exercise Clause in relation to taxation. The Court has held that the Establishment Clause prohibits the government from actively involving itself in religious activities but allows for a "benevolent neutrality" that enables religious organisations to exist without government sponsorship or interference. This interpretation has resulted in tax exemptions for religious institutions, with all 50 states and the District of Columbia providing various types of property tax exemptions for these organisations.

The federal government has exempted churches and other religious organisations from federal taxation since the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913. These exemptions are provided for religious properties, publications, and other related materials and activities. The courts have navigated the religion clauses of the First Amendment, with some scholars arguing that the two religion clauses are in conflict.

In conclusion, the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment protects the free exercise of religion and has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to include certain tax exemptions for religious institutions. These exemptions are designed to encourage the beneficial secular effects of religious organisations while maintaining a neutral stance on religious matters.

Understanding T-Tests: Sample Size and T-Table Usage

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Free Exercise Clause is found in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Free Exercise Clause states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof". It protects citizens' right to practice their religion as they please, as long as it does not conflict with "public morals" or a "compelling" government interest.

The Free Exercise Clause ensures that citizens have the liberty to hold, practice, and change religious beliefs freely according to the dictates of conscience. It prohibits government interference in religious belief and, within limits, religious practice.

![Religious liberty under the Free Exercise Clause. 1988 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61IX47b4r9L._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![[(Religious Liberty: 2: The Free Exercise Clause )] [Author: Douglas Laycock] [Jun-2011]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41Brdbcqb6L._AC_UY218_.jpg)