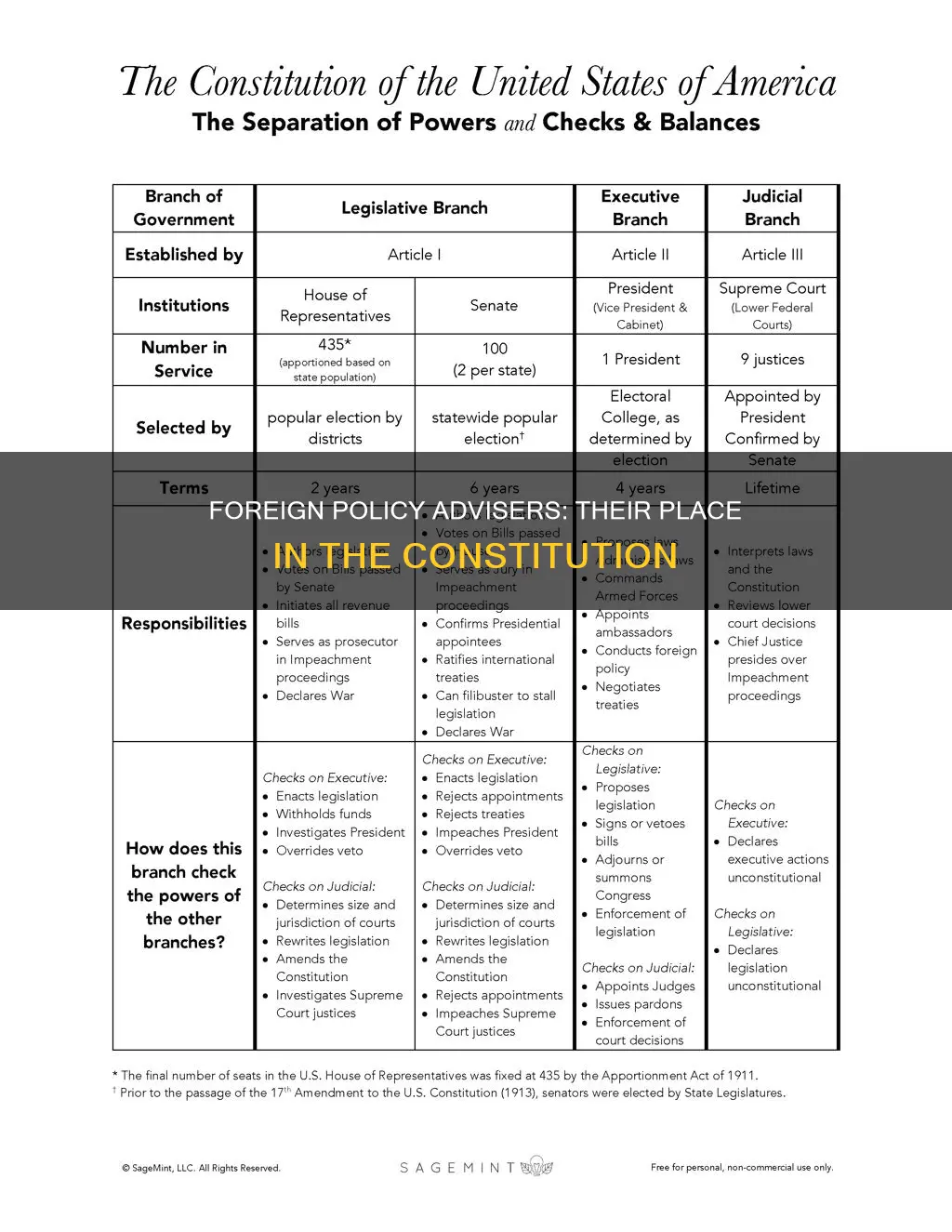

The U.S. Constitution outlines the division of foreign affairs powers between the President and Congress. Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution states that the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. This includes the power to negotiate treaties, appoint ambassadors, and make decisions regarding foreign policy. However, Congress also plays a significant role in foreign relations, as they have the power to approve treaties, regulate foreign commerce, impose import tariffs, and declare war. The debate over the extent of the President's foreign affairs powers has been ongoing since the Founding Era, with figures like Alexander Hamilton and James Madison offering differing interpretations of the Constitution's intent.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Foreign affairs powers | Shared between the president and Congress |

| Foreign policy powers | Vested in the president, with the ability to negotiate treaties and appoint ambassadors, ministers, and consuls |

| Recognition of foreign sovereigns | Exclusive to the Executive |

| Congress's role | Power to approve treaties, regulate foreign commerce, impose import tariffs, and raise revenue |

| Department of State | Created to lead foreign affairs, initially led by Thomas Jefferson |

Explore related products

$77.13 $124

What You'll Learn

The president's foreign affairs powers

The President of the United States is the Chief Diplomat of the country, as outlined in Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution. This means that the President has the power to negotiate with foreign governments, appoint ambassadors, and recognise foreign governments.

The President's role as Chief Diplomat involves representing the interests of the United States abroad. For example, President Clinton rallied international support to oust the Haitian military regime that had overthrown the nation's democratically elected president in a coup d'état. Clinton successfully assembled a coalition of 22 nations to oppose the Haitian dictatorship, which eventually led to the restoration of the rightful president.

While the President has significant foreign affairs powers, Congress also plays a role in foreign relations. According to the Constitution, Congress has the power to declare war and state the purpose of the war. Additionally, in matters of recognising new states, the President has historically invoked the judgment and cooperation of Congress, and Congress may legislate on matters preceding and following a presidential act of recognition.

The Cabinet: Constitutional or Conventional?

You may want to see also

Congress's foreign relations powers

The US Constitution does not explicitly outline the roles of Congress and the President in formulating foreign policy. However, it does grant Congress several powers that enable it to exert significant influence in this domain. These include the power to declare war, regulate commerce with foreign nations, appropriate government funds, and approve ambassadorial nominations and high-ranking executive branch officials.

One of Congress's most substantial foreign relations powers is its "power of the purse." As the body responsible for appropriating government funds, Congress can effectively control how money is spent, including on foreign policy initiatives. This allows Congress to shape foreign policy by imposing limitations or restrictions on the use of funds. For example, Congress has asserted its authority over the use of military force, as seen in debates about authorising the use of force against ISIL in Syria and Iran, where they sought a new resolution to counter the Administration's broader interpretation of the 2002 resolution.

Congress also plays a crucial role in treaty-making. While the President has the power to make treaties, it is with the advice and consent of the Senate. This collaborative dynamic between the President and Congress is a recurring theme in foreign policy formulation. For instance, in recognising new states, the President often involves Congress, and Congress can legislate on matters preceding and following a presidential act of recognition.

The Senate's role in approving ambassadorial nominations and high-ranking executive branch officials is another way Congress influences foreign relations. This power enables Congress to shape the diplomatic corps and ensure alignment with broader foreign policy goals.

Muslim Reps' Oath: Constitution or Religious Law?

You may want to see also

The president's ability to make treaties

The US Constitution's Treaty Clause (Article II, Section 2, Clause 2) grants the President the authority to make treaties, in collaboration with the Senate. This clause outlines the procedure for ratifying international agreements, with the President acting as the primary negotiator. The President has the sole power to negotiate treaties, and their role in treaty-making is to "ratify" or make the treaty by signing it and arranging for the deposit or exchange of the instrument.

The President's treaty-making power is not absolute, however. The advice and consent of the Senate are required for a treaty to be binding, with the force of federal law. While the Senate cannot prevent the President from negotiating a treaty, they do have the power to approve or disapprove of it, and can attach conditions or reservations. This dynamic between the President and the Senate in treaty-making was a compromise reached during the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

The implementation of a treaty into domestic law may require further action by Congress. The Supreme Court has held that Congress can abrogate a treaty through subsequent legislative action, even if it violates the treaty under international law. This was seen in the Medellin v. Texas case, which limited the President's ability to enforce an international agreement without Congress's explicit delegation.

The recognition of foreign governments is another aspect of foreign policy where the President and Congress play a role. The Executive has the exclusive authority to recognise foreign sovereigns, as seen in the case of the Spanish-American republics, Texas, Hayti, and Liberia. However, Congress can legislate on matters preceding and following a presidential act of recognition, which may undercut the policies that arise from recognition.

FDR's Constitution Conundrum: Rules Broken?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The president's ability to appoint ambassadors

The U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause gives the president the plenary power to nominate and appoint ambassadors, but this is subject to the approval of the Senate. This clause is designed to ensure accountability and prevent tyranny by separating powers between the president and the Senate. Alexander Hamilton defended the use of a public confirmation of officers, stating that it would prevent "cabal and intrigue" and the "scandalous bartering of votes and bargaining for places".

While the president has the power to nominate ambassadors, the Senate's role is advisory, and the president is not bound to their advice. The Senate can reject or confirm a nominee, and they have the power to impose requirements for the selection of foreign officers via statute. The Senate's confirmation power also extends to the appointment of other principal officers, such as Supreme Court Justices.

The Appointments Clause acts as a restraint on Congress, preventing them from filling offices with their supporters and infringing on the president's control over the executive branch. While Congress can create offices through statute, the president has the authority to nominate officers to fill those positions, ensuring a measure of accountability in staffing important government positions.

The Constitution Party: Understanding America's Political Landscape

You may want to see also

The power to declare war

The US Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war. This power is enshrined in Article I, Section 8, which grants Congress the authority to "lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States."

While the President has significant foreign affairs powers, the power to declare war remains with Congress. This was intentionally included in the Constitution by the Founding Fathers, who wanted to ensure that the power to take the nation to war was not vested in a single individual.

The debate over the respective powers of the President and Congress in foreign affairs is almost as old as the nation itself. In 1793, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison engaged in what became known as the Pacificus-Helvidius Debates, centering on the foreign affairs powers of the President. Hamilton argued that the executive power of the nation was vested in the President and that the foreign affairs power could not belong to the legislative or judicial departments.

On the other hand, Madison, who is known as the "Father of the Constitution", took a more expansive view of Congress's powers, arguing that the President's role was primarily confined to executing the laws made by Congress. This debate over the war powers of the President and Congress continues to this day, with scholars and politicians still discussing the appropriate balance of powers between the two branches of government.

While Congress has the power to declare war, the President has significant influence over foreign policy and can take actions that may lead to war. The President can negotiate treaties, appoint ambassadors, and take actions that fall under the umbrella of "foreign affairs powers," such as imposing sanctions or authorizing military strikes without a formal declaration of war.

The Constitution Signers: Were They All Christians?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The president has a number of foreign affairs powers, including the ability to negotiate treaties and appoint ambassadors, ministers, and consuls, with the advice and consent of the Senate.

Congress also has foreign relations powers, including the power to approve treaties negotiated by the president, regulate foreign commerce, impose import tariffs, and raise revenue.

The debate over the scope of the president’s foreign affairs powers dates back to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. The delegates agreed on a single person as the "President of the United States", with executive powers vested in the president. However, there has been ongoing discussion over where foreign affairs powers are shared between the president and Congress.

Some examples include President Wilson's nonrecognition of the government of Mexico in 1913, President Carter's termination of the Mutual Defense Treaty with Taiwan, and President Nixon's recognition of the People's Republic of China.