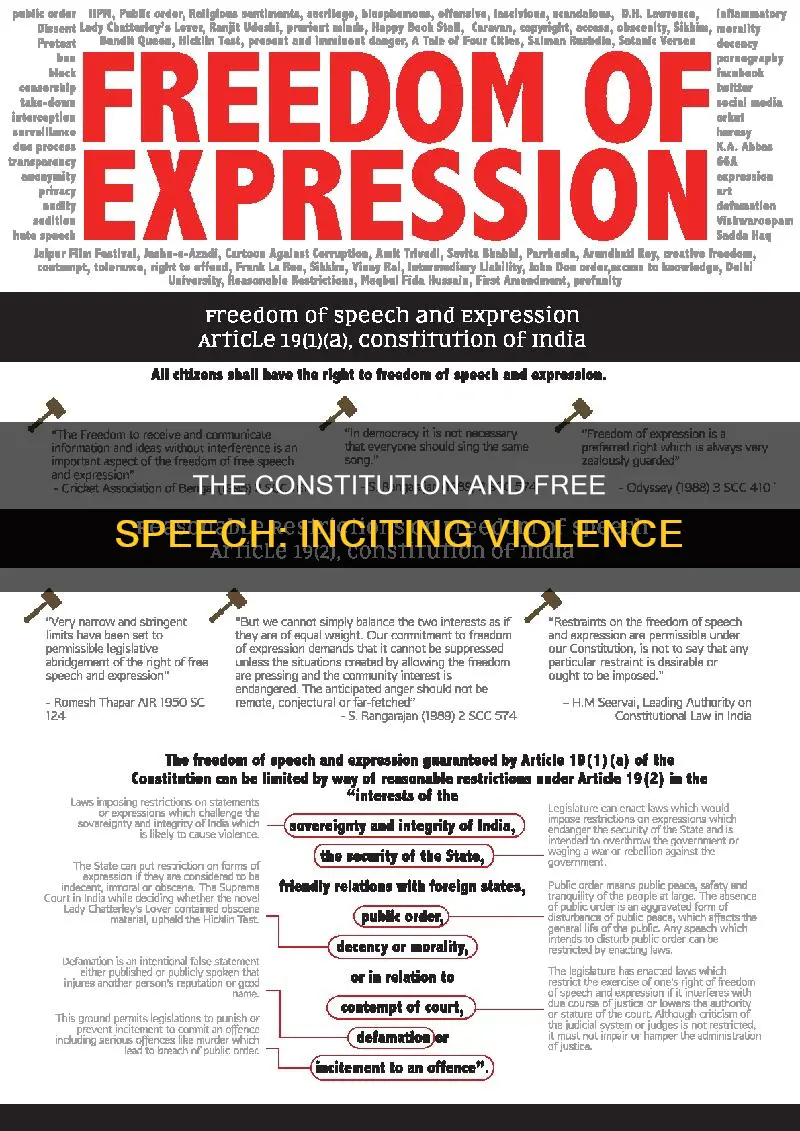

The First Amendment of the US Constitution protects freedom of speech, stating that Congress shall make no law...abridging freedom of speech. However, the Supreme Court has often struggled to determine what constitutes protected speech, and there are certain types of speech that are not protected. For example, speech that incites imminent lawless action is not protected by the First Amendment. The standard for determining whether speech incites imminent lawless action was established in the 1969 Supreme Court case Brandenburg v. Ohio, which clarified that speech is not protected if the speaker intends to incite a violation of the law that is imminent and likely. This case set a high bar for what constitutes incitement, ruling that even the hateful and violent rhetoric of a KKK leader was protected speech.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| First Amendment | The Constitution guarantees freedom of speech, but it does not mention inciting violence explicitly. However, the Supreme Court has interpreted the First Amendment to protect even offensive and hateful speech, unless it incites imminent lawless action. |

| Incitement Exception | The Court has ruled that speech inciting imminent violence or lawless action is not protected. This is known as the "incitement exception." |

| Clear and Present Danger Test | The Court uses the "clear and present danger" test to determine if speech crosses the line into incitement. This test considers the likelihood that the speech will result in imminent unlawful acts and whether the speaker intends to bring about such acts. |

| Brandenburg v. Ohio | In this landmark case, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction of a Ku Klux Klan member who had threatened violence against African Americans and Jews. The Court ruled that his speech was protected because it did not pose an imminent threat and did not advocate for immediate violence. |

| Limits on Governmental Power | The Constitution's protection of free speech, even speech that may be offensive or disturbing, serves as a crucial limit on governmental power and protects against censorship and abuse of power. |

| Application in Modern Contexts | The interpretation and application of these principles in the context of modern issues, such as online speech, social media, and hate speech, continue to evolve and are the subject of ongoing legal debates and challenges. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The First Amendment and unprotected speech

The First Amendment to the US Constitution, passed by Congress on September 25, 1789, and ratified on December 15, 1791, protects freedom of speech. It states:

> Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abriding the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

However, the First Amendment does not protect all speech in absolute terms. Certain categories of speech are considered "unprotected" and may be restricted. These include:

Incitement

Speech that is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action" is not protected by the First Amendment. This standard was set by the Supreme Court in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), which involved a case of Ku Klux Klan members using slurs and advocating violence. The Court ruled that their statements did not express an immediate or imminent intent to commit violence and thus were protected by the First Amendment.

True Threats

True threats are distinguishable from heated rhetoric. For a statement to be considered a true threat, it must be a serious expression of intent to commit an act of unlawful violence against a particular individual or group. The speaker does not need to intend to carry out the threat, but they must be aware that their words could be interpreted as threatening violence.

Fighting Words

The "fighting words" exception to the First Amendment covers face-to-face communications that are likely to provoke an immediate and violent reaction from the average listener. This exception is narrowly defined and rarely invoked.

Defamation

The First Amendment does not protect speech that defames a specific individual. Defamation is defined as a false statement that damages another person's reputation.

Commercial Speech

Commercial speech, such as advertising, receives limited protection under the First Amendment. False advertising and advertising that targets minors are not protected.

Intellectual Property Rights

Copyrights and trade secrets are exceptions to the First Amendment. Reproducing or distributing copyrighted material without permission is not protected and can result in legal consequences.

Military Speech

The government has broad powers to restrict the speech of military personnel, even if such restrictions would be unconstitutional for civilians. This exception is based on the principle that the military is a "specialized society" with stricter guidelines than civilian society.

Hate Speech

While hate speech is generally protected by the First Amendment, it may be regulated if it constitutes harassment or is motivated by hate and results in illegal conduct.

Strict Enforcement: China's One-Child Policy

You may want to see also

Fighting words and incitement

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution protects freedom of speech. However, there are limitations to this right, including the "fighting words" doctrine and incitement.

Fighting Words

The "fighting words" doctrine is a limitation on the freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment. It was established by the US Supreme Court in 1942 in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire. In this case, Walter Chaplinsky, a Jehovah's Witness, was arrested after calling a New Hampshire town marshal a "damned racketeer" and a "damned fascist" while preaching. The Court upheld the arrest, finding that "insulting or 'fighting words', those that by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace" are not protected by the First Amendment.

Over the years, the Court has narrowed the grounds for applying the "fighting words" doctrine. For example, in Street v. New York (1969), the Court overturned a statute prohibiting flag-burning and verbally abusing the flag, holding that mere offensiveness does not qualify as "fighting words". Similarly, in Cohen v. California (1971), the Court found that Paul Robert Cohen's wearing a jacket that said "fuck the draft" did not constitute "fighting words" because it was not directed at anyone personally.

Incitement

Incitement is speech that is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action". It is not protected by the First Amendment. The standard for incitement was established by the Supreme Court in 1969 in Brandenburg v. Ohio, which involved the arrest of Ku Klux Klan members under an Ohio criminal syndicalism law. The Court ruled that "the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action".

In determining whether speech constitutes incitement, courts consider the totality of the circumstances, including the context in which the speech was made. For example, in Hess v. Indiana (1973), the Supreme Court found that the defendant's speech was protected under the First Amendment because it amounted to nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time and therefore did not meet the imminence requirement.

Slavery's Dark Legacy in the Constitution

You may want to see also

True threats

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects an individual's right to free speech, even if the ideas put forth are offensive, immoral, or hateful. However, this protection does not extend to "true threats", a category of speech that includes obscenity, child pornography, fighting words, and the advocacy of imminent lawless action. True threats are statements intended to place the victim in fear of bodily harm or death, and can be prosecuted under state and federal criminal laws.

The Supreme Court has defined true threats as statements where the speaker intends to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence against a particular individual or group. The speaker need not intend to carry out the threat, but the prosecution must prove that they intended to communicate one. The Court has also clarified that intimidation can be prohibited as a type of true threat, where the speaker directs a threat to a person or group with the intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm or death.

In determining whether speech constitutes a true threat, courts have considered various factors, including the reaction of the recipient and other listeners, whether the threat was conditional, whether it was communicated directly to the victim, whether the maker of the threat had made similar statements in the past, and whether the victim had reason to believe that the maker of the threat had a propensity to engage in violence.

The Supreme Court has also distinguished true threats from political hyperbole. For example, in Watts v. United States (1969), the defendant, Robert Watts, an anti-Vietnam War protester, attended a public rally where he said, "If they ever make me carry a rifle, the first man I want to get in my sights is L.B.J." The Court held that Watts' remark was a form of political hyperbole and did not constitute a true threat, ruling that the statute criminalizing threats against the president was unconstitutional.

While the First Amendment protects free speech, it does not shield individuals from legal consequences for making true threats or inciting violence. The government can prosecute individuals who intentionally threaten another person with death or serious bodily harm, and whose language is reasonably perceived as threatening.

Understanding the Fundamentals of an Ampere

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Defining unprotected obscenity

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution protects the right to free speech, but the Supreme Court has determined that this protection does not extend to several categories of unprotected speech, including obscenity. Obscenity laws are concerned with prohibiting lewd or extremely offensive words or pictures in public.

The Supreme Court has ruled that obscenity is not protected by the First Amendment, but the courts must determine in each case whether the material in question is obscene. The portrayal of sex in art, literature, and scientific works is not sufficient reason to deny material the constitutional protection of freedom of speech and press. The Court defined material appealing to prurient interest as "material having a tendency to excite lustful thoughts", and defined prurient interest as "a shameful or morbid interest in nudity, sex, or excretion".

The Miller v. California case of 1973 prescribed the standards by which unprotected pornographic materials were to be identified. The Miller test for obscenity includes the following criteria: whether the average person sees the material as having/encouraging excessive sexual interest based on community standards; whether the material depicts or describes sexual conduct in a clearly offensive way as defined by the applicable state law; and whether the work, when considered in its entirety, "lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value".

The Court also disavowed and discarded the standard that a work must be "utterly without redeeming social value" to be suppressed. In determining whether material appeals to prurient interest or is patently offensive, the trier of fact, whether a judge or a jury, is not bound by a hypothetical national standard but may apply the local community standard where the trier of fact sits. It is the unprotected nature of obscenity that allows this inquiry; offensiveness to local community standards is a principle completely at odds with mainstream First Amendment jurisprudence.

Child pornography violates all three parts of the Miller test, and making or distributing such material is a crime. However, child pornography is unprotected by the First Amendment even when it is not obscene.

Executive Branch Membership: Who Are These Powerful Few?

You may want to see also

Freedom of speech restrictions

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees freedom of speech. It states: "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech." The intent of the drafters is clear: they believed that in a free society, people must be permitted to criticise the government and lobby for change.

However, while freedom of speech is a fundamental right, there are some limitations. The courts have addressed these restrictions over the years, and the definition of freedom of speech has evolved and been refined. The First Amendment does not protect speech that incites people to break the law, including committing acts of violence. This is known as the “imminent lawless action" test, established in 1969 in the Supreme Court case of Brandenburg v. Ohio. The Supreme Court ruled that "the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action."

The government may also restrict the time, place, or manner of speech if the restrictions are unrelated to the content of the speech and allow for alternative avenues of expression. For example, the government may restrict the use of loudspeakers in residential areas at night, limit demonstrations that block traffic, or ban picketing of people's homes.

Certain categories of speech are not protected from government restrictions, including incitement, defamation, fraud, obscenity, child pornography, fighting words, and threats. The Supreme Court has struggled to define "obscenity," and the exact definition remains unclear. However, since the 1980s, the definition has been narrow, and cursing or swearing is not considered obscene.

Speech by government employees, prisoners, and military personnel may be broadly restricted. Additionally, speech on government-owned property, such as sidewalks and parks, may be limited under certain circumstances.

Losing Cobra: Implications for Medicare Supplement GI Plans

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the First Amendment of the US Constitution protects free speech. However, there are some exceptions, including obscenity, fraud, child pornography, speech integral to illegal conduct, speech that incites imminent lawless action, and speech that violates intellectual property law.

The "imminent lawless action" test is a legal standard used by American courts to determine whether certain speech is protected under the First Amendment. Under this test, speech is not protected by the First Amendment if the speaker intends to incite a violation of the law that is both imminent and likely. The test was first established in 1969 in the Supreme Court case of Brandenburg v. Ohio.

A "true threat" is a statement in which the speaker expresses a serious intent to commit an act of unlawful violence against a specific individual or group. The speaker does not need to intend to carry out the threat, but they must intend to place the victim in fear of bodily harm or death.