The term political party traces its origins to the 17th century, emerging during a period of significant political transformation in England. The term party itself derives from the Latin word pars, meaning part or side, reflecting the division of political factions within a larger group. The concept gained prominence during the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the subsequent Restoration period, as groups like the Whigs and Tories coalesced around distinct ideologies and interests. These early factions laid the groundwork for organized political groups, which later evolved into modern political parties. The term was further solidified in the United States during the late 18th century, as the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties emerged, shaping the structure of political competition and governance that continues to define democratic systems today.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin of the Term | The term "political party" originated in 17th-century England during the Exclusion Crisis (1679–1681). |

| Historical Context | The term was first used to describe factions in Parliament: the "Court Party" (supporters of the King) and the "Country Party" (opponents of the King). |

| Key Figures | The term gained prominence during the debates over excluding James, Duke of York (later King James II), from the throne due to his Catholicism. |

| Evolution of Meaning | Initially, "party" referred to a group with shared interests or goals, often in opposition to another group, rather than a formal organization. |

| Formalization | The concept of political parties as organized entities with platforms, memberships, and structures developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly in the United States and Europe. |

| Modern Definition | Today, a political party is defined as an organized group that seeks to attain and exercise political power through electoral processes, often with a shared ideology or policy agenda. |

| Global Adoption | The term and concept of political parties spread globally with the rise of democratic systems and modern nation-states. |

| Etymology | The word "party" comes from the French partie, meaning "part" or "side," reflecting the idea of taking a side in a political dispute. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins in 17th Century England: Term emerged during the Exclusion Crisis, referring to factions supporting or opposing the King

- Influence of Classical Terms: Derived from Latin pars, meaning part, used to describe factions in ancient Rome

- American Adoption: Early U.S. political groups adopted party to describe Federalist and Democratic-Republican factions

- French Revolution Impact: French factions like Jacobins and Girondins popularized the term in revolutionary politics

- Global Spread in 19th Century: Colonialism and democratization spread the term political party worldwide

Origins in 17th Century England: Term emerged during the Exclusion Crisis, referring to factions supporting or opposing the King

The term "political party" owes its origins to the tumultuous political landscape of 17th-century England, specifically during the Exclusion Crisis of the 1670s and 1680s. This period was marked by intense debates over whether the Duke of York, a Catholic and the heir presumptive to the throne, should be excluded from the line of succession. The crisis polarized the English political elite into two distinct factions: those who supported the King and his heir (the Tories) and those who opposed them (the Whigs). These factions were not yet formal parties in the modern sense but were the precursors to organized political groups. The term "party" itself emerged as a label for these coalitions, derived from the Latin *pars*, meaning "part" or "side," reflecting their role as distinct sides in a political struggle.

Analyzing the Exclusion Crisis reveals how these factions operated. The Whigs, often associated with the landed gentry and commercial interests, argued for limiting the monarch’s power and excluding the Duke of York to prevent Catholic rule. The Tories, aligned with the Anglican establishment and the monarchy, defended the principle of hereditary succession and resisted any challenge to royal authority. These divisions were not merely ideological but also deeply personal, with leaders like Anthony Ashley Cooper (Earl of Shaftesbury) and John Wilmot (Earl of Rochester) spearheading their respective causes. The term "party" thus became a shorthand for identifying these competing interests, though it carried a somewhat negative connotation, implying partiality or bias rather than a unified political vision.

To understand the practical implications of this terminology, consider how these factions mobilized support. Whigs used pamphlets, petitions, and public meetings to rally opposition to the Duke of York, while Tories relied on royal patronage and the Church of England to solidify their base. These tactics laid the groundwork for modern party politics, as factions began to organize systematically to influence policy and public opinion. The Exclusion Crisis, therefore, was not just a constitutional debate but a crucible in which the concept of political parties was forged, shaped by the need to coordinate action and articulate shared goals.

A comparative perspective highlights the uniqueness of this development. While factions had existed in earlier political systems, such as ancient Rome or Renaissance Italy, the 17th-century English experience was distinct in its explicit use of the term "party" and its focus on constitutional issues. Unlike the informal alliances of the past, these factions were defined by their opposition or support for a specific policy—exclusion—and their efforts to shape the monarchy’s future. This specificity made the term "party" a useful tool for identifying and categorizing political actors, setting a precedent for later developments in democratic systems.

In conclusion, the Exclusion Crisis was a pivotal moment in the evolution of political parties. It introduced the term "party" as a way to describe organized factions with distinct agendas, rooted in the conflict between supporters and opponents of the King. This period demonstrated how political divisions could be institutionalized, laying the foundation for the party system that would dominate Western politics. By examining this historical context, we gain insight into the origins of a term that remains central to political discourse today, reminding us that even the most fundamental concepts have specific, often contentious, beginnings.

Understanding the Role and Functions of Political Parties in Democracy

You may want to see also

Influence of Classical Terms: Derived from Latin pars, meaning part, used to describe factions in ancient Rome

The term "political party" traces its linguistic roots to the Latin word *pars*, meaning "part." In ancient Rome, *pars* was used to describe factions or groups within the political landscape, often aligned with influential families or ideologies. These factions were not formalized parties in the modern sense but rather loose coalitions of interests vying for power. The concept of *pars* highlights the enduring human tendency to organize into competing groups, a dynamic that continues to shape politics today.

Analyzing the Roman context reveals how *pars* functioned as a precursor to modern political parties. Roman factions, such as the Optimates and Populares, were defined by their stances on wealth distribution, military expansion, and civic rights. While these groups lacked formal structures, they relied on patronage networks and rhetorical strategies to mobilize support. This early model of factionalism demonstrates how the idea of *pars* laid the groundwork for the organized, ideologically driven parties we recognize today.

To understand the transition from *pars* to "political party," consider the evolution of language and governance. As Latin influenced European languages, *pars* became *parti* in French and *party* in English, retaining its connotation of division. By the 17th century, the term "party" was widely used in England to describe political groupings like the Whigs and Tories. This linguistic continuity underscores how classical terminology adapted to new political realities, bridging ancient Rome and modern democracies.

A practical takeaway from this historical lineage is the recognition of political parties as natural outgrowths of human social organization. Just as Roman factions emerged from competing interests, modern parties reflect diverse ideologies and priorities. Understanding this classical origin encourages a nuanced view of party politics, emphasizing their role as mechanisms for representation rather than mere tools of division. By studying *pars*, we gain insight into the enduring structures of political competition and collaboration.

Finally, the influence of *pars* on the term "political party" serves as a reminder of the power of language to shape political institutions. The transition from a Latin word describing Roman factions to a universal term for organized political groups illustrates how ideas and terminology evolve across centuries. This historical perspective invites us to critically examine the role of parties in contemporary politics, ensuring they remain instruments of democracy rather than sources of fragmentation.

The Role of Third-Party Contributions in Shaping Political Landscapes

You may want to see also

American Adoption: Early U.S. political groups adopted party to describe Federalist and Democratic-Republican factions

The term "political party" found its way into American political lexicon during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period marked by intense ideological divisions. The Federalist and Democratic-Republican factions, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, respectively, were not initially referred to as parties. Instead, they were seen as loose coalitions of like-minded individuals. However, as their differences over issues like the role of the federal government, banking, and foreign policy deepened, the need for a unifying label became apparent. The term "party" emerged as a practical descriptor, reflecting the organized nature of these groups and their efforts to mobilize support for their agendas.

This adoption was not without controversy. Early American leaders, including George Washington, had warned against the dangers of faction in his Farewell Address, fearing it would undermine the young republic. Yet, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican groups embraced the term "party" as a way to legitimize their structures and strategies. They established networks of newspapers, held caucuses, and coordinated electoral campaigns, effectively laying the groundwork for modern political parties. This shift from informal alliances to formalized parties was a pragmatic response to the complexities of governing a diverse and expanding nation.

The use of "party" also served a strategic purpose. By labeling themselves as such, these factions could present a unified front, making it easier to rally supporters and challenge opponents. For instance, the Federalists used their party apparatus to advocate for a strong central government and close ties with Britain, while the Democratic-Republicans leveraged theirs to promote states’ rights and agrarian interests. This organizational clarity allowed voters to align themselves with specific ideologies, fostering a more structured political landscape.

Despite initial resistance to the idea of parties, their adoption marked a turning point in American politics. It transformed the way political power was contested and exercised, moving from ad hoc coalitions to enduring institutions. The Federalist and Democratic-Republican factions, by embracing the term "party," inadvertently created a framework that would shape U.S. politics for centuries. Their example demonstrates how language can evolve to meet the demands of a changing political environment, turning a once-controversial label into a cornerstone of democratic governance.

Practical takeaway: Understanding the origins of political parties highlights the importance of organization and branding in politics. For modern groups seeking to influence policy or win elections, adopting a clear identity and structure—much like the early Federalists and Democratic-Republicans—can be a powerful tool for mobilizing support and achieving long-term goals.

Are Political Party Donations Tax Deductible? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$79.99 $100

French Revolution Impact: French factions like Jacobins and Girondins popularized the term in revolutionary politics

The French Revolution, a tumultuous period of radical social and political upheaval, served as a crucible for the modern concept of political parties. Amidst the chaos, factions like the Jacobins and Girondins emerged as distinct ideological blocs, each advocating for their vision of France’s future. These groups were not merely coalitions of convenience but organized entities with clear platforms, membership structures, and strategies for influence. It was within this revolutionary fervor that the term "political party" gained currency, evolving from a vague descriptor of alliances into a formalized political institution.

Consider the Jacobins, a radical faction headquartered in the Dominican convent of Saint-Jacques, from which their name derives. They championed egalitarian ideals, centralization of power, and the execution of King Louis XVI. Their disciplined organization, with local clubs across France, demonstrated the power of a unified political movement. In contrast, the Girondins, named after the Gironde department, advocated for a more decentralized republic and initially opposed the king’s execution. The rivalry between these factions underscored the emergence of competing ideologies within a revolutionary framework, each vying for dominance through structured political action.

Analyzing their impact, the Jacobins and Girondins exemplified how factions could mobilize public opinion, control legislative bodies, and shape policy outcomes. Their debates in the National Assembly were not just ideological clashes but strategic maneuvers to consolidate power. This dynamic transformed the notion of political allegiance from personal loyalties to programmatic commitments, laying the groundwork for modern party systems. By the late 1790s, the term "party" had become synonymous with organized political groups, a far cry from its earlier, more informal usage.

To understand their legacy, examine how these factions operationalized their ideologies. The Jacobins’ use of propaganda, public rallies, and their newspaper, *Le Vieux Cordelier*, showcased early party tactics. Meanwhile, the Girondins’ reliance on regional support networks highlighted the importance of grassroots mobilization. These strategies, though born of necessity in a revolutionary context, became blueprints for future political parties worldwide. Practical takeaway: the French Revolution’s factions demonstrate that effective political organization requires both ideological clarity and tactical adaptability.

In conclusion, the French Revolution’s factions did more than fight for power—they redefined it. The Jacobins and Girondins, through their ideological fervor and organizational prowess, popularized the term "political party" as we understand it today. Their legacy is a reminder that political institutions are not static but evolve in response to historical pressures. For anyone studying political systems, the revolutionary era offers a vivid case study in how factions can crystallize into enduring political entities, shaping the course of nations.

Key Traits Defining a Political Party: Structure, Ideology, and Influence

You may want to see also

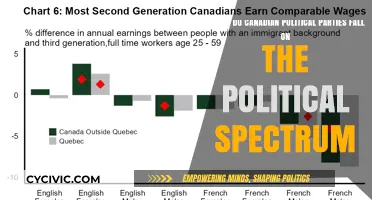

Global Spread in 19th Century: Colonialism and democratization spread the term political party worldwide

The 19th century was a pivotal era for the global dissemination of the term "political party," driven by the twin forces of colonialism and democratization. European powers, particularly Britain and France, exported their political systems to colonies across Asia, Africa, and the Americas. These systems often included the concept of organized political factions, which locals adapted to their contexts. For instance, in British India, the Indian National Congress emerged in 1885 as a platform for political representation, mirroring the party structures of its colonial ruler. This transplantation of ideas laid the groundwork for the term’s universal recognition.

Colonialism acted as both a catalyst and a constraint in this process. While it introduced the term "political party," it often limited its practical application by suppressing indigenous political movements. In Latin America, for example, colonial legacies of Spanish and Portuguese rule influenced early party formations, but these were frequently co-opted by elite factions. Despite these limitations, the exposure to European political models sparked debates about representation and governance, fostering the term’s integration into local lexicons.

Democratization, though uneven, further propelled the spread of political parties. The 19th century saw waves of democratic reforms in Europe and the Americas, inspiring similar movements elsewhere. In Japan, the Meiji Restoration and subsequent adoption of a parliamentary system in 1890 introduced political parties as a mechanism for competing interests. Similarly, in the Ottoman Empire, reforms like the Tanzimat era encouraged the formation of proto-parties advocating for constitutional governance. These examples illustrate how democratization, whether homegrown or externally influenced, solidified the term’s global relevance.

A comparative analysis reveals that the term’s adoption was shaped by local conditions. In regions with strong nationalist movements, like Ireland or Egypt, parties often emerged as vehicles for self-determination. Conversely, in settler colonies such as Australia and Canada, parties reflected the political divisions of their European origins. This diversity underscores the adaptability of the term, which transcended cultural and geographical boundaries while retaining its core function of organizing political competition.

Practical takeaways from this era include the importance of context in shaping political institutions. For modern nations building democratic frameworks, understanding the historical interplay of colonialism and democratization can inform more inclusive party systems. Additionally, studying 19th-century examples highlights the need for balancing external influences with local realities to ensure political parties serve as genuine instruments of representation rather than tools of domination. This historical lens offers valuable insights for contemporary political development.

Exploring the Diverse Political Parties Shaping Global Governance Today

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The term "political party" originated in the 17th century, primarily in England, during a period of political upheaval. It is derived from the Latin word "pars," meaning "part" or "faction," and was used to describe groups of individuals who aligned themselves with specific political ideologies or leaders.

The term was first formally used by English philosopher and politician John Locke in his writings during the late 17th century. Locke referred to factions or groups within government as "parties," particularly in the context of the Whigs and Tories, the early political groupings in England.

The concept of political parties spread globally through colonization, trade, and the influence of Enlightenment ideas. The American and French Revolutions further popularized the idea of organized political groups, leading to the establishment of formal political parties in the United States and Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.