The political party switch, often referred to as the Great Switch or the Realignment of American Politics, is a significant historical phenomenon in which the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States underwent a dramatic transformation in their ideological and demographic bases. This shift, which occurred primarily in the mid-20th century, saw the Democratic Party, once dominated by conservative Southerners, evolve into a more progressive and liberal coalition, while the Republican Party, previously associated with Northern progressivism, became the party of conservatism. The origins of this switch can be traced back to several key factors, including the Civil Rights Movement, the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the growing divide over issues such as states' rights, federal intervention, and social justice, which ultimately led to a realignment of political alliances and identities across the nation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | The political party switch refers to the realignment of the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States, primarily occurring in the mid-20th century. |

| Key Period | 1930s–1960s, with significant shifts during the Civil Rights Movement and the New Deal era. |

| Causes | - New Deal Policies: Franklin D. Roosevelt's programs attracted Southern conservatives to the Democratic Party initially. - Civil Rights Legislation: The Democratic Party's support for civil rights in the 1960s alienated Southern conservatives, pushing them toward the Republican Party. - Southern Strategy: The Republican Party's strategy to appeal to white Southern voters by opposing federal intervention in state affairs. |

| Regional Impact | The South shifted from predominantly Democratic to predominantly Republican, while the North and West became more solidly Democratic. |

| Key Figures | - Lyndon B. Johnson: Signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, accelerating the party switch. - Richard Nixon: Implemented the Southern Strategy, further solidifying the shift. |

| Long-Term Effects | - Republican Dominance in the South: The GOP became the dominant party in the South. - Democratic Strength in Urban Areas: The Democratic Party gained stronger support in urban and coastal regions. |

| Modern Alignment | - Republican Party: Associated with conservatism, lower taxes, and states' rights. - Democratic Party: Associated with liberalism, social welfare programs, and civil rights. |

| Ongoing Debate | Historians and political scientists continue to analyze the extent and timing of the switch, with some arguing it was gradual and others pointing to specific events as catalysts. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Post-Civil War realignment: Southern Democrats shifted to GOP over civil rights, altering regional party dominance

- New Deal coalition: FDR’s policies attracted Southern conservatives, temporarily solidifying Democratic support in the South

- Civil Rights Act (1964): GOP’s opposition to federal intervention drew Southern whites away from Democrats

- Southern Strategy: Nixon’s appeal to racial conservatism accelerated the South’s shift to Republican

- Urban vs. rural divide: Democrats gained urban voters, while Republicans captured rural and suburban areas

Post-Civil War realignment: Southern Democrats shifted to GOP over civil rights, altering regional party dominance

The post-Civil War era laid the groundwork for a seismic shift in American political allegiances, particularly in the South. Initially, the Democratic Party dominated the region, rooted in its defense of states' rights and opposition to Republican-led Reconstruction policies. However, the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century fractured this loyalty. As the national Democratic Party embraced civil rights legislation, Southern Democrats felt alienated, viewing these policies as federal overreach and a threat to their traditional way of life. This ideological rift set the stage for a realignment that would redefine regional party dominance.

Consider the 1964 Civil Rights Act, a pivotal moment in this transformation. President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Democrat, championed the bill, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. While the act was a landmark victory for civil rights, it came at a political cost. Johnson reportedly remarked, "We have lost the South for a generation," recognizing that Southern Democrats, who had long resisted federal intervention, would defect to the Republican Party. This prediction proved accurate as the GOP, under leaders like Barry Goldwater and later Richard Nixon, capitalized on Southern grievances with their "Southern Strategy," appealing to voters opposed to racial integration and federal mandates.

The shift was not immediate but gradual, unfolding over decades. In the 1960s and 1970s, Southern Democrats began to identify more with Republican stances on issues like states' rights, economic conservatism, and social traditionalism. The GOP’s emphasis on "law and order" and its opposition to busing and affirmative action resonated with white Southerners who felt their cultural and economic interests were under attack. By the 1990s, the South had largely flipped, with Republicans dominating state legislatures, governorships, and congressional delegations in what was once the Democratic stronghold.

This realignment had profound implications for both parties. For Democrats, the loss of the South forced them to recalibrate their strategy, focusing on urban and coastal regions while struggling to regain traction in rural and Southern areas. For Republicans, the Southern shift solidified their hold on national politics, providing a reliable voter base that would shape policy and electoral strategies for decades. The transformation also altered the ideological landscape, with the GOP becoming the party of the South and the Democrats increasingly associated with progressive, urban values.

Practical takeaways from this realignment highlight the importance of understanding regional identities and historical grievances in political strategy. For instance, candidates seeking to bridge the divide must address economic anxieties and cultural concerns without alienating core constituencies. Additionally, studying this shift offers lessons in coalition-building: the GOP’s success in the South was not just about opposition to civil rights but also about aligning with local values and priorities. As political landscapes continue to evolve, this historical realignment serves as a reminder that party loyalties are not static but can be reshaped by ideological and cultural forces.

Veterans' Political Leanings: Which Party Dominates Their Allegiance?

You may want to see also

New Deal coalition: FDR’s policies attracted Southern conservatives, temporarily solidifying Democratic support in the South

The New Deal coalition, forged under Franklin D. Roosevelt's leadership, marked a seismic shift in American political alignment, particularly in the South. Traditionally a stronghold of conservative Democrats since Reconstruction, the region's allegiance to the party was deepened and temporarily solidified by FDR's expansive social and economic policies. These programs, designed to combat the Great Depression, resonated with Southern conservatives who saw them as a means to preserve their agrarian economy and social order. For instance, the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) provided subsidies to farmers for reducing crop production, benefiting large Southern landowners. Similarly, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) brought electrification and economic development to a poverty-stricken region, earning FDR loyalty even among those who might otherwise have resisted federal intervention.

However, the coalition’s strength lay not just in economic policies but also in FDR’s strategic appeal to Southern cultural values. By framing the New Deal as a defense of traditional American values against radical change, he bridged the ideological gap between Northern progressives and Southern conservatives. This alignment was further reinforced by the Democratic Party’s dominance in the "Solid South," where one-party rule suppressed Republican competition. Yet, this unity was fragile, built on a shared opposition to the Depression rather than a unified vision for the future. Southern conservatives supported the New Deal insofar as it served their immediate interests, but their commitment to states' rights and racial hierarchy remained unchanged.

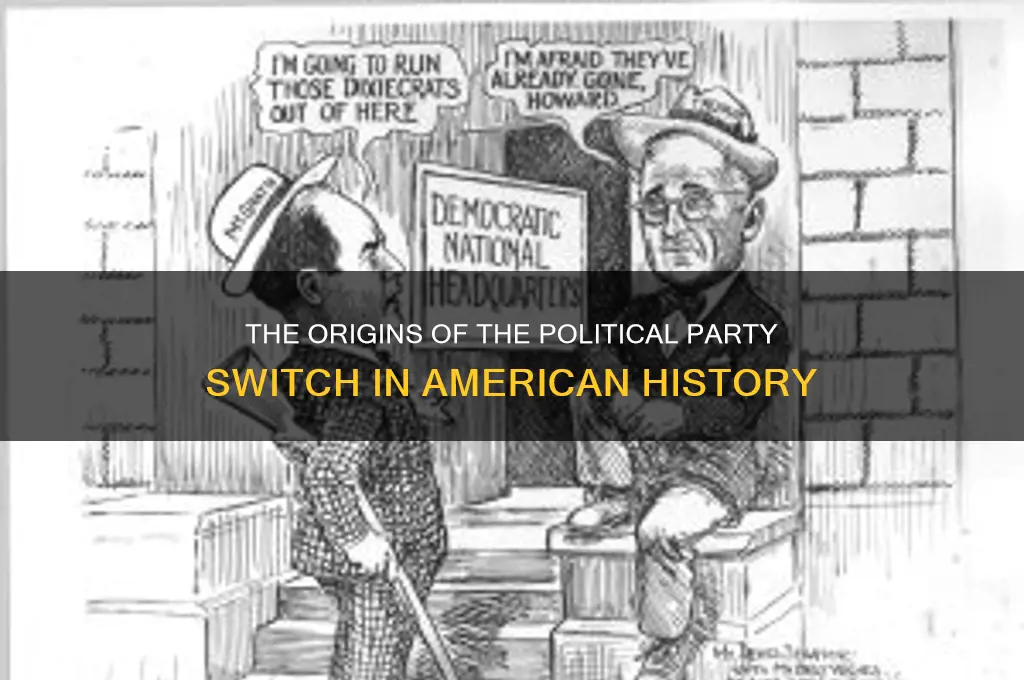

The temporary nature of this coalition becomes evident when examining its unraveling. As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the mid-20th century, FDR’s successors, particularly Harry Truman and Lyndon B. Johnson, pushed for federal intervention to dismantle segregation. This directly challenged Southern conservatives’ core beliefs, leading to a gradual realignment. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 accelerated this shift, as Southern conservatives began to defect to the Republican Party, which increasingly embraced states' rights and opposition to federal overreach.

To understand the New Deal coalition’s impact, consider it as a political paradox: a progressive agenda that temporarily united disparate factions. For practitioners of political strategy, the lesson is clear: coalitions built on crisis response are inherently unstable. They require continuous alignment of interests, which the New Deal coalition lacked once the Depression ended and civil rights emerged as a defining issue. Practical takeaways include the importance of addressing both economic and cultural concerns when building political alliances and recognizing the limits of temporary unity in the face of deeper ideological divides.

In conclusion, the New Deal coalition exemplifies how policy can reshape political landscapes, even if temporarily. FDR’s ability to attract Southern conservatives was a masterclass in pragmatic politics, but the coalition’s fragility underscores the challenge of sustaining alliances across ideological divides. This historical episode serves as a cautionary tale for modern policymakers: while crisis can create opportunities for unity, lasting realignment requires addressing the underlying values and beliefs of diverse constituencies.

Why Some Political Reformers Failed to Achieve Lasting Change

You may want to see also

Civil Rights Act (1964): GOP’s opposition to federal intervention drew Southern whites away from Democrats

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 stands as a pivotal moment in American history, reshaping not only racial equality but also the political landscape. While the Act’s passage marked a triumph for civil rights, it also exposed deep ideological divides, particularly within the Democratic Party. Southern Democrats, long resistant to federal intervention in state affairs, found themselves at odds with their Northern counterparts, who championed the legislation. This rift created an opening for the Republican Party, which strategically capitalized on Southern whites’ growing resentment toward federal overreach. By framing their opposition to the Act as a defense of states’ rights, the GOP began to peel away a demographic that had been a Democratic stronghold for generations.

Consider the political calculus at play. The Democratic Party, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, pushed for the Civil Rights Act despite knowing it would alienate Southern conservatives. Johnson famously remarked, “We have lost the South for a generation,” acknowledging the short-term electoral cost of advancing racial equality. Meanwhile, the Republican Party, led by figures like Barry Goldwater, opposed the Act on grounds of states’ rights, a position that resonated with Southern whites who viewed federal intervention as an infringement on their way of life. Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign, though unsuccessful nationally, won five Southern states, signaling a shift in regional allegiances. This was not merely a reaction to the Act itself but a broader rejection of the federal government’s expanding role in social and economic matters.

The GOP’s strategy was both deliberate and effective. By aligning itself with the states’ rights narrative, the party positioned itself as the defender of Southern traditions and autonomy. This messaging tapped into long-standing cultural and economic anxieties, particularly among rural and working-class whites who felt marginalized by national policies. For instance, the Act’s provisions on desegregation and voting rights were seen by some as threats to local control and community norms. The Republican Party’s ability to frame these concerns as part of a larger struggle against federal overreach laid the groundwork for the “Southern Strategy,” a long-term plan to attract white voters away from the Democrats.

However, this shift was not immediate or uniform. It took years for the GOP to fully capitalize on the discontent sown by the Civil Rights Act. The process accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s, as Republicans like Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan refined their appeals to Southern voters. Nixon’s “law and order” rhetoric and Reagan’s emphasis on limited government resonated with those who felt betrayed by the Democratic Party’s embrace of federal activism. By the 1990s, the South had become a Republican stronghold, a transformation rooted in the GOP’s opposition to the Civil Rights Act and its broader critique of federal intervention.

In retrospect, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 serves as a case study in how policy decisions can reshape political identities. For Southern whites, the Act became a symbol of unwanted federal intrusion, driving them into the arms of a Republican Party that promised to protect their interests. This realignment was not just about race, though racial tensions played a significant role; it was also about power, autonomy, and the role of government in American life. The GOP’s success in leveraging these issues underscores the enduring impact of the Act on the nation’s political divide. Understanding this history is crucial for anyone seeking to grasp the origins of the modern party system and the regional polarization that defines it.

Unions vs. Businesses: Who Funds Political Parties More?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.96 $35

Southern Strategy: Nixon’s appeal to racial conservatism accelerated the South’s shift to Republican

The 1960s marked a seismic shift in American politics, as the South, once a Democratic stronghold, began its steady march toward the Republican Party. Richard Nixon's "Southern Strategy" played a pivotal role in this transformation, leveraging racial conservatism to appeal to white Southern voters disillusioned with the Democratic Party's embrace of civil rights. This strategy didn't invent racial tensions, but it exploited them, accelerating a realignment that reshaped the nation's political landscape.

Nixon's approach was subtle yet calculated. He avoided overt racism, instead employing coded language and policies that resonated with those resistant to racial integration. His emphasis on "law and order," for instance, was a dog whistle to those fearing social upheaval brought about by the civil rights movement. Similarly, his opposition to forced busing and support for "states' rights" appealed to those seeking to maintain racial segregation in schools and local governance.

This strategy found fertile ground in the South, where decades of Democratic dominance had been built on a foundation of white supremacy. The Democratic Party's increasing support for civil rights legislation, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, alienated many white Southerners. Nixon's Southern Strategy offered them a new political home, one that seemed more aligned with their anxieties and desires.

The impact was profound. While the shift wasn't immediate, Nixon's victories in Southern states in the 1968 and 1972 elections signaled a significant change. Over time, the Republican Party solidified its hold on the South, becoming the dominant force in a region that had once been solidly Democratic. This realignment wasn't just about race, but race was a central factor, and Nixon's Southern Strategy played a crucial role in exploiting and accelerating this shift.

Third Parties' Influence: Shaping Elections and Political Landscapes

You may want to see also

Urban vs. rural divide: Democrats gained urban voters, while Republicans captured rural and suburban areas

The urban-rural political divide in the United States didn’t emerge overnight; it’s a product of decades of shifting demographics, economic changes, and cultural polarization. By the mid-20th century, Democrats dominated the South with their conservative, agrarian policies, while Republicans held sway in the North with their urban, industrial base. However, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s catalyzed a realignment. Democrats’ embrace of civil rights alienated Southern conservatives, while Republicans, under figures like Richard Nixon, capitalized on rural and suburban anxieties about social change. This marked the beginning of Democrats gaining ground in diverse, densely populated urban centers, while Republicans solidified their hold on rural and suburban areas.

Consider the contrasting priorities of urban and rural voters to understand this divide. Urban areas, often hubs of diversity and economic innovation, tend to prioritize issues like public transportation, affordable housing, and social equity. Democrats’ policies on healthcare expansion, climate action, and immigration reform resonate with these voters. In contrast, rural and suburban voters frequently emphasize local control, economic stability, and traditional values. Republicans’ focus on tax cuts, gun rights, and deregulation aligns with these concerns. For instance, while urban voters may support increased funding for public schools, rural voters often prefer school choice and reduced federal intervention. This mismatch in priorities has deepened the political chasm between these groups.

To bridge this divide, policymakers must address the unique needs of both urban and rural communities. For urban areas, investing in infrastructure and education can foster economic growth and reduce inequality. Rural regions, meanwhile, require targeted initiatives to combat job loss and population decline, such as broadband expansion and agricultural subsidies. However, these solutions must be tailored to local contexts. A one-size-fits-all approach risks alienating voters on both sides. For example, while urban voters may support green energy initiatives, rural communities dependent on fossil fuel industries need transition programs to avoid economic hardship.

The urban-rural divide also reflects broader cultural and ideological differences. Urban centers, with their diverse populations, often embrace progressive values like multiculturalism and LGBTQ+ rights. Rural areas, with their homogenous populations and strong religious traditions, tend to favor conservative social norms. This cultural gap is exacerbated by media echo chambers and partisan rhetoric, making compromise increasingly difficult. To mitigate this, community-based dialogues and cross-partisan collaborations can help build understanding. For instance, joint rural-urban projects on issues like food security or disaster preparedness can highlight shared interests and reduce polarization.

Ultimately, the urban-rural divide is not insurmountable, but it requires intentional effort to address. Democrats must engage rural voters by demonstrating how their policies benefit local economies, while Republicans need to appeal to urban voters by acknowledging the importance of social equity and sustainability. Practical steps, such as bipartisan infrastructure bills or regional development programs, can create common ground. By recognizing the distinct needs and values of urban and rural communities, policymakers can work toward a more inclusive and cohesive political landscape. The challenge lies not in erasing differences, but in finding ways to coexist and collaborate despite them.

Urban Political Machines: Power, Patronage, and City Governance Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The political party switch refers to the realignment of the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States during the mid-20th century, where the Democratic Party shifted from being predominantly conservative to liberal, and the Republican Party shifted from being predominantly liberal to conservative.

The political party switch primarily took place between the 1930s and 1960s, with key events like the New Deal, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Southern Strategy accelerating the realignment.

The switch was driven by several factors, including the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights and social liberalism under President Lyndon B. Johnson, the Republican Party’s adoption of the Southern Strategy to appeal to conservative Southern voters, and shifting regional and ideological alliances.

The Civil Rights Movement led to a divide within the Democratic Party, as conservative Southern Democrats opposed federal civil rights legislation. This pushed many Southern conservatives to align with the Republican Party, while the Democratic Party increasingly became associated with progressive and liberal policies.

The Southern Strategy, employed by Republicans like Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, targeted conservative white voters in the South who were disillusioned with the Democratic Party’s support for civil rights. This strategy helped solidify the Republican Party’s dominance in the South and accelerated the ideological realignment of both parties.