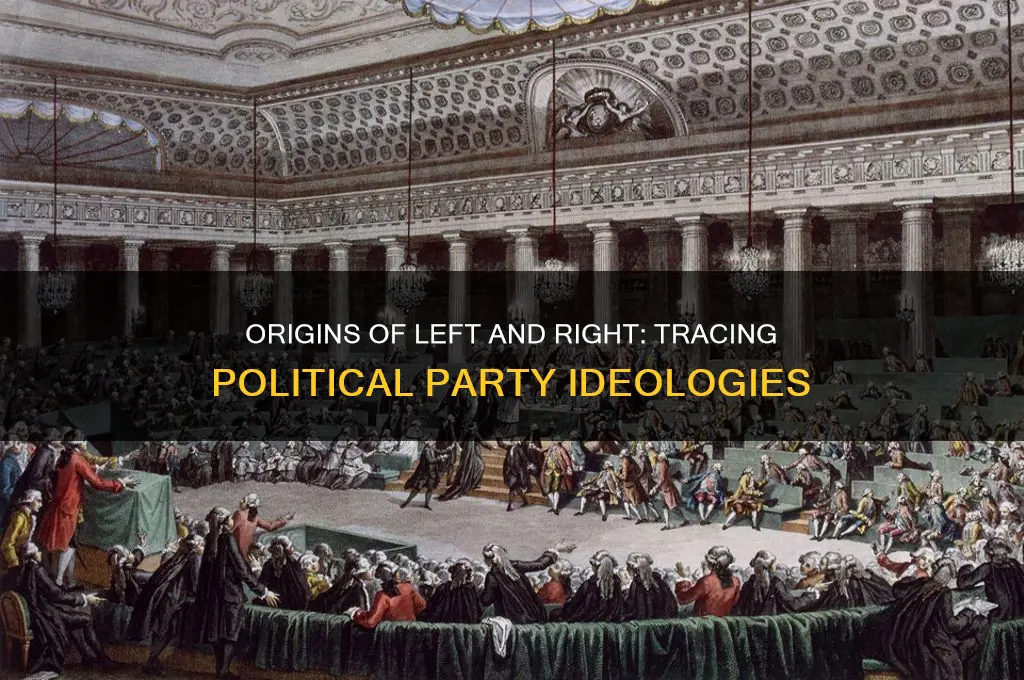

The concepts of left and right political parties emerged during the French Revolution in the late 18th century, specifically in the National Assembly of 1789. Deputies who supported radical changes, such as the abolition of the monarchy and the redistribution of wealth, sat on the left side of the assembly, while those who favored preserving traditional institutions and hierarchies sat on the right. This spatial division quickly became symbolic of broader ideological differences, with the left generally associated with progressive, egalitarian, and often socialist or liberal ideals, and the right linked to conservatism, tradition, and free-market capitalism. Over time, these labels evolved and adapted across different cultures and political systems, but the fundamental distinction between left and right remains a cornerstone of modern political discourse, shaping how ideologies, policies, and parties are categorized and understood globally.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin of Terms | The terms "left" and "right" originated during the French Revolution (1789–1799). Deputies supporting radical change sat on the left of the National Assembly, while those favoring tradition and monarchy sat on the right. |

| Historical Development | The concepts evolved over time, with the left traditionally associated with egalitarianism, social reform, and workers' rights, and the right associated with conservatism, free markets, and traditional hierarchies. |

| Modern Left | Emphasizes social equality, progressive taxation, public services, environmental sustainability, and minority rights. Examples: Democratic Party (USA), Labour Party (UK), Social Democratic Party (Germany). |

| Modern Right | Focuses on individual liberty, free markets, limited government, national sovereignty, and traditional values. Examples: Republican Party (USA), Conservative Party (UK), Christian Democratic Union (Germany). |

| Global Variations | The meanings of left and right vary by country. For instance, in some European countries, the left may include communist or socialist parties, while in the U.S., the left is more centrist compared to European standards. |

| Economic Policies | Left: Redistribution of wealth, higher taxes on the wealthy, strong welfare state. Right: Lower taxes, deregulation, emphasis on private enterprise. |

| Social Policies | Left: Support for LGBTQ+ rights, abortion rights, multiculturalism. Right: Emphasis on traditional family values, restrictions on abortion, national identity. |

| Environmental Policies | Left: Strong focus on climate action, renewable energy, and regulation of industries. Right: Often skeptical of extensive environmental regulations, prioritizing economic growth. |

| Foreign Policy | Left: Tends toward diplomacy, international cooperation, and multilateralism. Right: Emphasizes national security, unilateral action, and strong military. |

| Evolution in the 21st Century | The rise of populism, identity politics, and issues like globalization and immigration have blurred traditional left-right distinctions in some contexts. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Origins in the French Revolution

The French Revolution birthed the political concepts of "left" and "right," a legacy that continues to shape global politics. This division emerged during the National Assembly’s debates in 1789, where seating arrangements became a visual metaphor for ideological differences. Supporters of the monarchy and traditional privileges sat to the right of the president’s chair, while advocates for radical change and popular sovereignty clustered to the left. This physical separation crystallized into a symbolic divide that persists today.

Consider the specific issues that drove this split. The right, dominated by conservatives, sought to preserve the monarchy and the influence of the Church, fearing the chaos of rapid reform. In contrast, the left, led by figures like Maximilien Robespierre, pushed for a republic, secularism, and the redistribution of wealth. The debate over the *Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen* exemplified this tension: the left championed universal rights, while the right resisted measures that threatened established hierarchies. This dynamic laid the groundwork for modern political polarization.

To understand the practical implications, examine the aftermath of the Revolution. The left’s radical phase, the Reign of Terror, demonstrated the dangers of unchecked idealism, while the right’s eventual restoration of monarchy under Napoleon highlighted the resilience of traditional power structures. These outcomes underscore a critical lesson: the left-right divide is not merely about ideology but about the balance between progress and stability. For modern political movements, this history serves as a cautionary tale—radical change must be tempered by pragmatism, and tradition must adapt to survive.

A comparative analysis reveals how this French model influenced global politics. The left-right spectrum became a universal framework, but its meaning evolved. In the U.S., for instance, the left is associated with social liberalism, while in France, it retains a stronger socialist tradition. Yet, the core distinction remains: the left prioritizes equality and collective welfare, while the right emphasizes individual liberty and order. This adaptability ensures the left-right paradigm’s enduring relevance, even as its specifics shift across cultures and eras.

Finally, for those studying or engaging in politics, the French Revolution offers a practical takeaway: seating arrangements matter. The physical organization of legislative bodies continues to reflect and reinforce ideological divisions. Whether in parliaments or town hall meetings, spatial dynamics can shape discourse and alliances. By recognizing this, participants can navigate political landscapes more effectively, leveraging the symbolism of left and right to advocate for their causes. The Revolution’s legacy is not just historical—it’s a living tool for understanding and influencing power.

Can Political Parties Operate as Limited Companies? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Early American Party Divisions

The roots of left and right political divisions in America trace back to the late 18th century, emerging from debates over the Constitution and the role of government. The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal role. This early split laid the groundwork for ideological divisions that persist in American politics, though the specific issues and labels have evolved.

Consider the Federalist Party, often seen as the precursor to modern conservatism. They prioritized economic development, industrialization, and a robust executive branch. Their policies, such as the creation of the First Bank of the United States, were designed to stabilize the young nation’s economy. Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans, akin to early progressives, feared centralized power and favored a more decentralized government aligned with the interests of farmers and the common man. This ideological clash over the size and scope of government remains a defining feature of left-right politics today.

A key example of this division played out during George Washington’s presidency, when Hamilton’s financial plans sparked fierce opposition from Jefferson and his allies. The debate over the national debt, taxation, and the role of banking institutions highlighted the emerging fault lines between what would later be called “left” and “right.” Federalists leaned toward a more interventionist government, while Democratic-Republicans resisted policies they saw as favoring the elite. This dynamic underscores how early American party divisions were not just about personalities but fundamental philosophical differences.

To understand these divisions practically, examine the 1796 presidential election, the first contested election in U.S. history. Federalist John Adams narrowly defeated Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson, who became vice president due to the electoral system at the time. This election revealed the deepening polarization between urban, commercial interests (Federalists) and rural, agrarian ones (Democratic-Republicans). It also demonstrated how party platforms began to align with broader ideological camps, a pattern that continues in modern politics.

In conclusion, early American party divisions were not merely organizational structures but reflections of deeper ideological conflicts. By studying the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, we see the origins of debates over centralization, economic policy, and the role of government that define left-right politics today. These early divisions remind us that political labels are not static but evolve in response to societal changes, yet their core tensions remain remarkably consistent.

Do Political Parties Fund Their Candidates? Unveiling Financial Support Secrets

You may want to see also

Evolution in 19th-Century Europe

The 19th century in Europe was a crucible for the crystallization of left and right political ideologies, shaped by the tumultuous interplay of industrialization, revolution, and intellectual ferment. The French Revolution of 1789 laid the groundwork, but it was the seating arrangement in the National Assembly—radicals on the left, conservatives on the right—that provided the spatial metaphor for political division. By the 1800s, this division evolved beyond mere seating into distinct philosophical camps. The left, associated with liberalism, socialism, and demands for equality, emerged as a response to the exploitation of the working class and the rigid hierarchies of the ancien régime. The right, rooted in conservatism and traditionalism, sought to preserve established institutions, often aligning with monarchy, aristocracy, and religious authority.

Industrialization acted as a catalyst, exacerbating the divide. The rise of factories and urban centers created a new proletariat, whose dire conditions fueled left-wing movements advocating for labor rights, universal suffrage, and economic redistribution. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ *Communist Manifesto* (1848) became a rallying cry for the left, while conservatives on the right warned of the dangers of upheaval and championed free-market capitalism as a bulwark against radical change. The revolutions of 1848, sweeping across Europe, exemplified this clash: leftists pushed for democratic reforms, while right-wing forces suppressed these uprisings to maintain order.

Nationalism further complicated the left-right spectrum in 19th-century Europe. While often associated with the right due to its emphasis on cultural homogeneity and state power, nationalism could also be co-opted by the left, as seen in movements for national self-determination in Italy and Germany. This duality highlights the fluidity of these ideologies, which were not yet rigidly defined. For instance, Giuseppe Mazzini’s Young Italy movement blended left-wing republicanism with nationalist fervor, blurring the lines between the two camps.

Practical tip: To understand this era, examine primary sources like parliamentary debates, pamphlets, and newspapers. These reveal how terms like “left” and “right” were used in context, showing their evolving meanings. For instance, the British Reform Act of 1832, which expanded suffrage, was championed by Whigs (early liberals) but opposed by Tories (conservatives), illustrating the left-right divide in action.

By the late 19th century, the left-right framework had become a dominant lens for political discourse, though its meanings varied by country. In France, the left was synonymous with republicanism and secularism, while in Germany, it was tied to social democracy. The right, meanwhile, ranged from moderate conservatives to reactionaries seeking a return to pre-revolutionary order. This diversity underscores the complexity of 19th-century Europe’s political evolution, where the concepts of left and right were not static but dynamic, shaped by the era’s unique challenges and opportunities.

The Great Shift: Did Political Parties Switch Positions After 1912?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Global Spread Post-World War II

The aftermath of World War II reshaped the global political landscape, accelerating the spread of left and right political ideologies beyond their European origins. Decolonization movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America sought self-governance, often aligning with socialist or communist principles (left) as a reaction to colonial exploitation. Simultaneously, Western powers, particularly the United States, promoted capitalist and democratic models (right) through economic aid and alliances like NATO. This ideological tug-of-war, known as the Cold War, became the framework for the global adoption of left-right political divisions.

Consider the case of India, which gained independence in 1947. The Indian National Congress, led by figures like Jawaharlal Nehru, embraced a mixed economy with socialist leanings, reflecting left-wing ideals of state intervention and social welfare. In contrast, Pakistan’s early alignment with the United States and its adoption of free-market policies exemplified a right-wing approach. Such patterns repeated across newly independent nations, where the choice between left and right often hinged on historical grievances, economic strategies, and Cold War allegiances.

However, the global spread of these ideologies was not uniform. In Latin America, left-wing movements like Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution directly challenged U.S.-backed right-wing dictatorships. Meanwhile, in Western Europe, social democratic parties (center-left) and Christian democratic parties (center-right) dominated, blending elements of both ideologies to create welfare states. This hybridization highlights how left-right distinctions adapted to local contexts, often losing their original European rigidity.

A critical takeaway is that the post-WWII era institutionalized the left-right spectrum as a global political language. The Cold War forced nations to align with either the socialist (left) or capitalist (right) blocs, even if these labels oversimplified complex domestic realities. For instance, African nations like Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah adopted left-wing pan-Africanism, while others, like South Africa, entrenched right-wing apartheid regimes. This polarization, though often artificial, cemented the left-right framework as a tool for understanding global politics.

Practical tip: When analyzing post-WWII political movements, avoid reducing them solely to left or right labels. Instead, examine how these ideologies interacted with local histories, economic needs, and Cold War pressures. For example, the Non-Aligned Movement sought to reject both blocs, illustrating the limitations of a binary framework in a multipolar world. Understanding this nuance is key to grasping the era’s political dynamics.

Understanding Cadre Political Parties: Structure, Role, and Influence Explained

You may want to see also

Modern Left-Right Spectrum Shifts

The traditional left-right political spectrum, rooted in the seating arrangements of the French National Assembly during the 18th century, has undergone significant shifts in recent decades. Once defined by economic policies—left favoring redistribution and right advocating free markets—the spectrum now incorporates a broader range of issues, including social justice, environmentalism, and cultural identity. These shifts reflect evolving global priorities and the rise of new political movements that challenge conventional categorizations.

Consider the Green parties, which emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, blending left-wing economic policies with a focus on environmental sustainability. While traditionally aligned with the left, their emphasis on ecological responsibility has attracted voters from across the spectrum, blurring the lines between left and right. Similarly, the rise of populist movements, such as those led by figures like Bernie Sanders in the U.S. and Marine Le Pen in France, has further complicated the spectrum. Sanders champions left-wing economic policies but appeals to working-class voters who might otherwise lean right, while Le Pen combines right-wing nationalism with left-leaning economic protectionism.

To navigate these shifts, it’s instructive to examine how issues like immigration and globalization have reshaped political identities. In Europe, for instance, left-wing parties historically supportive of open borders now face internal divisions as working-class constituents express concerns about job competition. Conversely, some right-wing parties have softened their stance on immigration to appeal to urban, liberal-minded voters. This fluidity underscores the need to reassess the left-right spectrum as a dynamic framework rather than a static one.

A comparative analysis of the U.S. and Europe highlights further nuances. In the U.S., the Democratic Party has shifted leftward on social issues like LGBTQ+ rights and racial justice, while the Republican Party has embraced cultural conservatism and economic populism. In contrast, European politics often sees left-wing parties advocating for stronger EU integration, while right-wing parties push for national sovereignty. These differences illustrate how the left-right spectrum adapts to regional contexts, making it a versatile yet complex tool for understanding political ideologies.

For practical application, individuals can use these shifts to better engage with political discourse. Start by identifying core values rather than rigidly adhering to a single party or label. For example, if environmental sustainability is a priority, explore how both left and right parties address this issue. Similarly, when discussing contentious topics like immigration, recognize the economic and cultural factors driving diverse perspectives. By embracing the spectrum’s fluidity, voters can make more informed decisions and contribute to a more nuanced political dialogue.

Roman Polanski's Political Affiliations: Unraveling the Director's Party Ties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The concepts of left and right political parties originated during the French Revolution in the late 18th century, specifically in the National Assembly of 1789.

The terms were derived from the seating arrangement in the National Assembly, where radicals sat on the left side, advocating for revolutionary change, while conservatives sat on the right, supporting the monarchy and traditional order.

Over time, "left" came to represent progressive, egalitarian, and socialist ideals, while "right" became associated with conservatism, free markets, and traditional values. These meanings have adapted to cultural and historical contexts globally.

No, the concepts spread internationally as nations adopted parliamentary systems. They became universal shorthand for political ideologies, though their specific meanings vary by country.

While still widely used, the terms are increasingly seen as oversimplifications, as modern politics often involves complex issues that don't fit neatly into left or right categories. However, they remain foundational in political discourse.