When one political party draws voting districts, a practice known as gerrymandering, it can significantly skew electoral outcomes in their favor by manipulating the boundaries of districts to dilute the voting power of opponents or concentrate their supporters. This strategic redistricting often results in oddly shaped districts that prioritize partisan advantage over fair representation, undermining democratic principles and reducing competitive elections. Critics argue that gerrymandering disenfranchises voters, distorts political accountability, and perpetuates one-party dominance, while proponents may claim it reflects legitimate political strategy. Efforts to combat this practice include independent redistricting commissions and legal challenges, but its persistence highlights ongoing tensions between partisan interests and equitable electoral systems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Term | Gerrymandering |

| Definition | The practice of drawing voting district boundaries to favor one political party. |

| Primary Purpose | To consolidate power by creating districts that dilute opposition votes. |

| Methods | - Cracking: Splitting opposition voters across multiple districts. |

| - Packing: Concentrating opposition voters into a few districts. | |

| Legal Status | Legal but subject to judicial review if deemed discriminatory. |

| Impact on Elections | Often results in uncompetitive elections and skewed representation. |

| Recent Examples (U.S.) | - North Carolina (2020s): Republican-drawn maps challenged in court. |

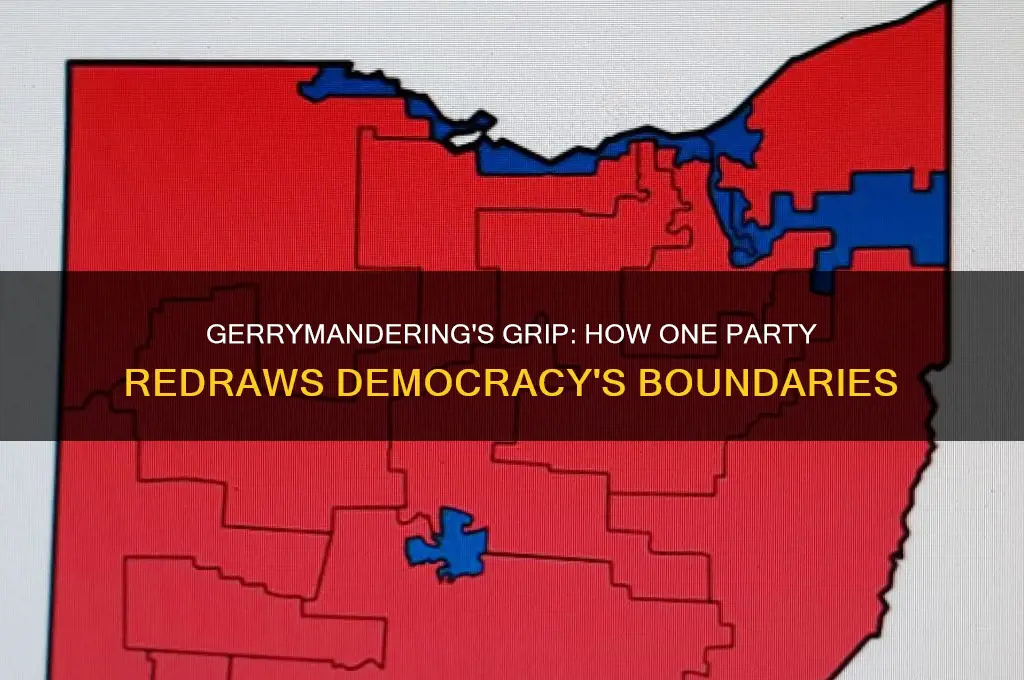

| - Ohio (2020s): Republican-drawn maps struck down for partisan bias. | |

| Countermeasures | - Independent redistricting commissions. |

| - Judicial intervention to enforce fairness. | |

| Public Opinion | Majority of Americans support nonpartisan redistricting. |

| Technological Influence | Advanced mapping software enables precise partisan advantage. |

| Global Prevalence | Common in countries with winner-takes-all electoral systems. |

| Historical Origin | Named after Elbridge Gerry (1812), whose district resembled a salamander. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Gerrymandering Techniques: How districts are shaped to favor a party’s electoral outcomes

- Legal Challenges: Court cases and laws addressing unfair redistricting practices

- Impact on Elections: Effects on voter representation and election results

- Independent Commissions: Role of non-partisan groups in drawing fair districts

- Historical Examples: Notable instances of gerrymandering in U.S. history

Gerrymandering Techniques: How districts are shaped to favor a party’s electoral outcomes

The practice of gerrymandering involves manipulating the boundaries of electoral districts to favor one political party over another. This is achieved through strategic shaping of districts, often resulting in bizarre, non-compact shapes that dilute the voting power of the opposing party. One common technique is "cracking," where voters from the opposing party are spread across multiple districts, ensuring they are always in the minority and unable to win a seat. For example, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Democratic voters were divided into several districts, preventing them from achieving a majority in any single one. This method effectively minimizes the opposing party’s representation, even if they have significant statewide support.

Another technique is "packing," which concentrates voters from the opposing party into a single district, allowing them to win that seat overwhelmingly while reducing their influence in surrounding districts. This was evident in Maryland’s 6th congressional district, where Republican voters were packed into one district, making neighboring districts safer for Democrats. While packing guarantees a win for the opposing party in one district, it maximizes the gerrymandering party’s wins in others. The trade-off? A single district with a lopsided victory margin but a broader electoral advantage for the party in power.

"Hijacking" is a more sophisticated method where a district’s boundaries are redrawn to include a small number of voters from the gerrymandering party’s strongholds, tipping the balance in their favor. This technique often involves appending geographically unrelated areas to a district, such as connecting urban and rural regions with no natural connection. For instance, in Illinois’s 4th congressional district, the district was drawn in a narrow, winding shape to connect heavily Democratic areas, ensuring a Democratic win while isolating Republican voters in adjacent districts.

To combat these techniques, courts and reformers often rely on metrics like the "efficiency gap," which measures the difference between the two parties’ "wasted votes"—votes cast for a losing candidate or surplus votes for a winning candidate. A high efficiency gap suggests gerrymandering, as seen in Wisconsin’s 2010 redistricting, where Republicans secured a supermajority despite winning only 48.6% of the statewide vote. Practical tips for identifying gerrymandering include examining district compactness, checking for unnatural shapes, and comparing election results to statewide voter preferences.

Ultimately, gerrymandering undermines democratic principles by distorting representation and silencing minority voices. While it’s a legal practice in many jurisdictions, its ethical implications are profound. Voters can protect their rights by advocating for independent redistricting commissions, supporting transparency in the redistricting process, and using data tools to analyze district maps. By understanding these techniques, citizens can better recognize and challenge efforts to manipulate electoral outcomes.

How Political Parties Select and Nominate Their Candidates

You may want to see also

Legal Challenges: Court cases and laws addressing unfair redistricting practices

Unfair redistricting, often termed gerrymandering, has sparked numerous legal battles across the United States, as courts grapple with the delicate balance between political power and constitutional rights. One landmark case, *Gill v. Whitford* (2018), brought the issue to the forefront of national attention. The Supreme Court, in a 9-0 decision, declined to rule on the merits of the case but established a critical framework for future challenges. The Court emphasized that plaintiffs must demonstrate concrete and particularized harm, a standard that has since shaped how gerrymandering cases are litigated. This ruling underscored the judiciary’s role in policing the boundaries of partisan mapmaking while leaving room for further legal evolution.

To challenge unfair redistricting effectively, plaintiffs often rely on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and the First Amendment’s freedom of association. In *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019), the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts lack authority to address partisan gerrymandering claims, deeming them nonjusticiable political questions. However, this decision did not preclude state courts from intervening under state constitutions. For instance, in *Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania* (2018), the state’s highest court struck down a Republican-drawn map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, redrawing districts to ensure fairness. This highlights the importance of state-level litigation as a viable pathway for reform.

Legislative efforts to curb gerrymandering have also gained traction, with several states adopting independent redistricting commissions. California’s Proposition 11 (2008) and Proposition 20 (2010) transferred redistricting authority from the legislature to a 14-member commission, comprising Democrats, Republicans, and independents. This model has been replicated in states like Arizona and Michigan, where voter-approved initiatives have minimized partisan influence in mapmaking. Such commissions are not without flaws—critics argue they can be susceptible to political appointments—but they represent a practical step toward depoliticizing the process.

Despite progress, legal challenges to gerrymandering remain complex. Courts must navigate the tension between respecting legislative authority and safeguarding democratic principles. In *Moore v. Harper* (2023), the Supreme Court rejected the independent state legislature theory, affirming that state courts can review redistricting plans under state constitutions. This decision preserved a crucial check on partisan excesses, ensuring that state judiciaries remain active participants in the fight against unfair maps. As litigation continues, advocates must focus on building robust legal arguments, leveraging state-level reforms, and fostering public awareness to drive meaningful change.

Will County IL Politics: Local Leaders, Issues, and Community Impact

You may want to see also

Impact on Elections: Effects on voter representation and election results

The practice of one political party drawing voting districts, known as gerrymandering, has profound implications for voter representation and election outcomes. By strategically reshaping district boundaries, the dominant party can dilute the voting power of opponents and consolidate its own support base. This manipulation often results in districts that are either overwhelmingly favorable to one party or so evenly split that they become battlegrounds, distorting the principle of "one person, one vote." For instance, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Republicans drew maps that secured them 10 out of 13 congressional seats despite winning only 53% of the statewide vote, illustrating how gerrymandering can amplify a party’s power beyond its actual voter support.

Consider the mechanics of how gerrymandering affects voter representation. When districts are drawn to pack opposition voters into a few districts, their influence is minimized, as those districts become safe seats for the opposing party. Simultaneously, cracking—spreading opposition voters across multiple districts—dilutes their ability to sway election results. This undermines the concept of proportional representation, where the number of seats a party wins should roughly reflect its share of the popular vote. For example, in Maryland, Democrats have historically drawn districts that pack Republican voters into one district, ensuring Democratic dominance in the remaining seats. Such tactics disenfranchise voters by making their ballots less impactful in determining election outcomes.

The consequences of gerrymandering extend beyond individual elections, shaping long-term political landscapes. When one party consistently controls redistricting, it can entrench its power for a decade or more, stifling competition and reducing incentives for politicians to appeal to a broad electorate. This polarization can lead to more extreme policies, as representatives focus on pleasing their party’s base rather than moderates or independents. In states like Ohio, gerrymandered maps have contributed to a lack of competitive races, with incumbents often running unopposed or facing token opposition. This diminishes voter engagement and perpetuates a cycle of political stagnation.

To mitigate these effects, reforms such as independent redistricting commissions have been proposed. States like California and Arizona have adopted such bodies, which remove partisan influence from the map-drawing process. These commissions prioritize criteria like compactness, contiguity, and adherence to existing political boundaries, resulting in fairer representation. For instance, California’s 2020 redistricting led to more competitive races and a closer alignment between statewide vote share and seat distribution. Voters and advocates can push for similar reforms by supporting ballot initiatives, lobbying legislators, and participating in public hearings during the redistricting process.

Ultimately, the impact of gerrymandering on elections underscores the need for transparency and fairness in redistricting. When one party draws voting districts, it distorts voter representation, skews election results, and undermines democratic principles. By understanding these effects and advocating for impartial redistricting processes, citizens can help restore balance to electoral systems and ensure that every vote counts equally. Practical steps include staying informed about redistricting timelines, engaging with local advocacy groups, and using tools like redistricting simulations to visualize the potential impact of proposed maps.

Ricky Polston's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Independent Commissions: Role of non-partisan groups in drawing fair districts

The practice of gerrymandering, where one political party manipulates voting district boundaries to favor their electoral outcomes, has long undermined democratic principles. Independent commissions, composed of non-partisan or bipartisan members, emerge as a critical countermeasure. These groups are tasked with redrawing district lines based on objective criteria such as population equality, geographic contiguity, and respect for communities of interest, rather than partisan advantage. By removing the self-dealing incentive from the process, independent commissions aim to restore fairness and public trust in electoral systems.

Consider the case of California, which established its Citizens Redistricting Commission in 2008. This 14-member body, comprising five Democrats, five Republicans, and four members from neither party, successfully redrew state and congressional districts following the 2010 census. The commission’s transparency—holding public meetings and accepting input from citizens—ensured accountability. Studies show California’s districts became more competitive, with a 15% increase in "swing" seats compared to previous maps. This example illustrates how independent commissions can break the cycle of partisan manipulation and foster more representative outcomes.

However, establishing effective independent commissions is not without challenges. Selection processes must be rigorous to prevent partisan infiltration. For instance, Arizona’s Independent Redistricting Commission uses a multi-step process involving a bipartisan legislative committee and a state commission to appoint members. Critics argue that even non-partisan members may harbor implicit biases, but evidence suggests these commissions still outperform partisan-led efforts. A 2020 Brennan Center analysis found states with independent commissions had significantly fewer gerrymandered districts than those drawn by legislatures.

To maximize the impact of independent commissions, certain best practices should be adopted. First, clear, non-partisan criteria must guide map-drawing, such as minimizing county and city splits. Second, public participation should be encouraged through accessible hearings and digital platforms for submitting map proposals. Third, commissions should be adequately funded to ensure they can operate without external influence. For instance, Michigan’s Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission received $4 million in 2020, enabling it to conduct extensive outreach and hire expert staff.

In conclusion, independent commissions represent a proven solution to the problem of partisan gerrymandering. By prioritizing fairness over political gain, these non-partisan groups can redraw districts that better reflect the will of the electorate. While challenges remain, the success of commissions in states like California and Arizona demonstrates their potential to transform electoral integrity. As more states adopt this model, the hope is that democracy itself will be strengthened, one fair district at a time.

Jason Kelce's Political Party: Unraveling His Political Affiliations and Views

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: Notable instances of gerrymandering in U.S. history

The practice of gerrymandering, where one political party manipulates voting district boundaries to gain an unfair advantage, has deep roots in U.S. history. One of the earliest and most infamous examples dates back to 1812 in Massachusetts. Governor Elbridge Gerry signed a redistricting bill that created a district resembling a salamander, sparking the term "gerrymander." This district was so contorted that it blatantly favored the Democratic-Republican Party, illustrating how early politicians exploited cartographic creativity to secure political dominance. This case set a precedent for future manipulations, demonstrating that even the Founding Fathers’ contemporaries were not immune to such tactics.

Fast forward to the post-Civil War era, and gerrymandering became a tool to suppress African American voting rights. In the late 19th century, Southern states used redistricting to dilute the political power of newly enfranchised Black voters. For instance, in North Carolina, districts were drawn to pack Black voters into a few areas, minimizing their influence in state and federal elections. This strategic segregation of voters laid the groundwork for Jim Crow laws and underscores how gerrymandering has historically been intertwined with racial disenfranchisement.

The 20th century saw gerrymandering evolve into a more sophisticated and partisan practice. One notable example is the 1960s redistricting in Illinois, where Democrats drew a district so convoluted it was dubbed the "earmuff district" due to its shape. This design aimed to protect incumbent representatives by packing Republican voters into a single district, ensuring Democratic dominance in surrounding areas. This case highlights how gerrymandering can be used to entrench political power, often at the expense of fair representation.

In recent decades, the 2000s redistricting in Texas exemplifies modern gerrymandering’s boldness. In 2003, Republicans, led by Congressman Tom DeLay, redrew the state’s districts mid-decade, a highly unusual move. This effort resulted in a significant shift of power, allowing Republicans to gain several seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. The Supreme Court later struck down parts of the plan for violating the Voting Rights Act, but the episode demonstrated the lengths to which parties will go to secure electoral advantages.

These historical examples reveal a recurring theme: gerrymandering is a persistent and adaptable tool for political manipulation. From its early days in Massachusetts to its modern iterations in Texas, it has been used to suppress minority voices, protect incumbents, and skew electoral outcomes. Understanding these cases not only sheds light on past injustices but also serves as a cautionary tale for addressing gerrymandering in contemporary politics.

The Origins of Political Parties in the United States: A Historical Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The term is "gerrymandering," which refers to the practice of manipulating the boundaries of electoral districts to favor one political party or group.

Gerrymandering can dilute the voting power of opposition supporters by spreading them across multiple districts or concentrate them into a few districts, ensuring the party in power wins more seats than their vote share would otherwise justify.

While gerrymandering is not explicitly illegal, it can be challenged in court if it violates constitutional principles, such as the Equal Protection Clause or the Voting Rights Act, particularly if it discriminates based on race.

Solutions include establishing independent or bipartisan redistricting commissions, using algorithmic or mathematical models to draw districts, and implementing stricter legal standards to ensure fairness and transparency in the process.