The question of when something becomes political is complex and multifaceted, as it hinges on the interplay between power, ideology, and societal structures. At its core, something is considered political when it involves or affects the distribution of power, resources, or decision-making within a community, organization, or society. This can manifest in explicit ways, such as government policies or elections, but it also extends to seemingly apolitical areas like culture, education, and personal choices, which often reflect or challenge underlying systems of authority and inequality. For instance, discussions about climate change, gender roles, or even fashion can become political when they intersect with broader debates about justice, representation, and control. Ultimately, the political nature of a topic is shaped by its potential to influence or disrupt the status quo, making it a dynamic and context-dependent concept.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Involves Power Dynamics | Relates to the distribution, exercise, or contestation of power in society or institutions. |

| Affects Public Policy | Influences laws, regulations, or government decisions impacting the public. |

| Involves Collective Action | Requires or results from group efforts, movements, or organized behavior. |

| Addresses Resource Allocation | Deals with how resources (e.g., money, land, services) are distributed or controlled. |

| Involves Ideological Conflict | Reflects competing beliefs, values, or worldviews (e.g., left vs. right, liberalism vs. conservatism). |

| Impacts Social Structures | Affects systems like class, race, gender, or institutions (e.g., education, healthcare). |

| Involves Governance | Relates to decision-making processes in public or private institutions. |

| Has Public Consequences | Affects the broader community, not just individuals or private interests. |

| Involves Representation | Deals with who speaks for or represents specific groups or interests. |

| Is Subject to Debate | Invites differing opinions, disagreements, or negotiations among stakeholders. |

| Involves Identity or Group Interests | Relates to the rights, recognition, or interests of specific social, cultural, or ethnic groups. |

| Crosses Personal and Public Spheres | Blurs the line between private life and public issues (e.g., reproductive rights, workplace policies). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Personal vs. Political: When do individual actions or beliefs become part of a larger political discourse

- Institutional Influence: How do institutions shape what is considered political in society

- Power Dynamics: When does the distribution or exercise of power make an issue political

- Public vs. Private: At what point do private matters enter the political sphere

- Collective Action: When does group behavior or advocacy transform into a political movement

Personal vs. Political: When do individual actions or beliefs become part of a larger political discourse?

The line between personal and political is often blurred, as individual actions and beliefs can intersect with broader societal structures and power dynamics. At its core, something becomes political when it relates to the organization and governance of society, involving questions of power, resources, and decision-making. Personal choices, such as how one votes, what they consume, or how they raise their children, can carry political weight when they reflect or challenge prevailing norms, policies, or systems. For instance, choosing to buy locally sourced food may seem like a personal decision, but it can align with political movements advocating for sustainability and economic fairness. Thus, the political dimension emerges when individual actions or beliefs connect to collective issues or systemic change.

Individual actions or beliefs transition into the political realm when they engage with public discourse or impact others beyond the individual. For example, a person’s stance on climate change might remain personal until they advocate for policy changes, join protests, or influence community behavior. Similarly, personal experiences, such as facing discrimination, can become political when they are framed as part of a larger struggle for equality. This shift occurs when individuals articulate their experiences in ways that highlight systemic injustices, thereby linking the personal to the political. As feminist scholar Carol Hanisch famously stated, “The personal is political,” emphasizing that private issues often stem from public, structural inequalities.

The context in which actions or beliefs are expressed also determines their political significance. In polarized societies, even seemingly neutral choices can be politicized. For instance, wearing a mask during a pandemic may be a health decision, but it can become political when it aligns with or opposes partisan views on government mandates. Similarly, religious or cultural practices can enter political discourse when they are debated in terms of national identity, rights, or public policy. This politicization often occurs when individual choices or beliefs are perceived to challenge or reinforce existing power structures, making them part of a larger ideological or policy debate.

Another critical factor is the extent to which individual actions or beliefs mobilize collective action or influence public opinion. When personal convictions inspire others to organize, protest, or demand change, they become inherently political. For example, a single person’s decision to boycott a company may have little impact, but if it sparks a widespread movement, it enters the political sphere. Social media has amplified this dynamic, allowing personal stories and beliefs to gain visibility and shape public discourse rapidly. In this way, the political nature of individual actions often depends on their ability to resonate with and mobilize broader audiences.

Ultimately, the distinction between personal and political is not fixed but fluid, shaped by societal values, historical context, and power relations. What is considered personal in one era or culture may be politicized in another. For instance, discussions of mental health were once confined to private conversations but have since become part of political agendas advocating for healthcare reform and social support. Recognizing when individual actions or beliefs become political requires understanding how they intersect with systemic issues and contribute to ongoing debates about justice, equality, and governance. By examining these intersections, we can better navigate the complex relationship between the personal and the political.

Revolutionary Change: Do Political Parties Fuel or Hinder Progress?

You may want to see also

Institutional Influence: How do institutions shape what is considered political in society?

Institutions play a pivotal role in defining and shaping what is considered political within a society. By their very nature, institutions—such as governments, legal systems, educational bodies, and media organizations—establish norms, rules, and frameworks that dictate how individuals and groups interact with power, authority, and decision-making processes. These structures inherently politicize certain issues by determining which topics are worthy of public debate, policy intervention, or legal regulation. For instance, governments often designate areas like taxation, foreign policy, and public safety as inherently political, while institutions like schools may frame civic engagement and historical narratives in ways that reflect political ideologies. Thus, institutions act as gatekeepers, deciding what enters the realm of political discourse and what remains outside it.

The influence of institutions on what is deemed political is also evident in their ability to create and enforce boundaries between the "public" and "private" spheres. For example, legal institutions often define issues like marriage, reproductive rights, or workplace conditions as political by subjecting them to legislation and judicial review. Conversely, matters traditionally considered private, such as personal beliefs or family dynamics, may be politicized when institutions intervene—as seen in debates over religious practices or parenting styles. This dynamic highlights how institutions not only reflect societal values but also actively shape them, often in ways that align with the interests of those in power. By controlling the narrative around what constitutes political action, institutions can marginalize certain voices or elevate specific agendas.

Educational institutions further contribute to this process by imparting knowledge and shaping perceptions of what is political. Curricula, textbooks, and teaching methodologies often embed political ideologies, whether explicitly or implicitly, influencing how students understand civic life, history, and societal structures. For example, the way a nation’s founding or historical conflicts are taught can either reinforce or challenge dominant political narratives. Similarly, universities and research bodies often determine which issues are studied and funded, thereby influencing which topics gain political traction. By controlling access to knowledge and framing discourse, educational institutions play a critical role in defining the parameters of political engagement.

Media institutions are another powerful force in shaping what is considered political. Through news coverage, entertainment, and social platforms, media organizations prioritize certain issues, frame debates, and influence public opinion. For instance, the decision to highlight a protest, a policy change, or a social movement as "political" can mobilize public attention and resources. Conversely, issues that receive little media coverage may be depoliticized, even if they have significant societal implications. The rise of digital media has further complicated this dynamic, as algorithms and user-generated content can both amplify and distort political discourse. Thus, media institutions act as intermediaries between events and their political interpretation, wielding considerable influence over what society perceives as politically relevant.

Finally, the interplay between institutions and societal norms ensures that the definition of "political" is not static but evolves over time. Institutions often respond to—and sometimes resist—shifts in public sentiment, technological advancements, and global trends. For example, issues like climate change, gender equality, or digital privacy have gained political prominence as institutions adapt to new challenges and demands. At the same time, institutions can entrench certain definitions of what is political, making it difficult for emerging issues to gain recognition. This tension underscores the dynamic relationship between institutions and society, where the former both reflect and shape the latter’s understanding of politics. Ultimately, institutional influence is a key determinant of how we identify, engage with, and contest what is considered political in our lives.

Did Political Parties Switch Platforms? A Peer-Reviewed Analysis

You may want to see also

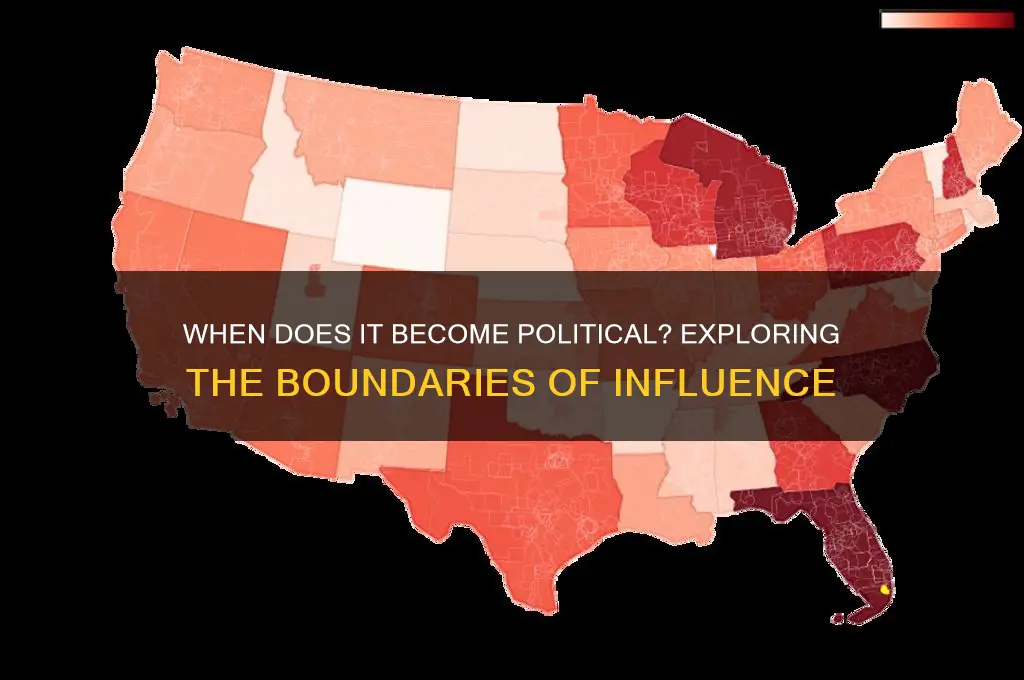

Power Dynamics: When does the distribution or exercise of power make an issue political?

The distribution and exercise of power are fundamental aspects of politics, and they play a crucial role in determining when an issue becomes political. At its core, politics involves the allocation and contestation of power, whether in the form of authority, resources, or influence. When power dynamics come into play, an issue often transcends its surface-level concerns and enters the realm of politics. This occurs because power inherently involves relationships between individuals, groups, or institutions, and these relationships are shaped by interests, hierarchies, and control. For instance, decisions about resource allocation—such as funding for education or healthcare—become political when they reflect or reinforce power imbalances between different social groups or regions. The act of deciding who gets what, when, and how is inherently political because it involves the exercise of authority and the imposition of one group’s will over another.

An issue becomes political when the distribution of power is unequal or contested. Power imbalances, whether based on class, race, gender, or other social categories, create tensions that politicize matters. For example, discussions about minimum wage are political because they involve negotiations between employers (who hold economic power) and workers (who seek fair compensation). The exercise of power by one group to maintain or challenge the status quo transforms the issue into a political struggle. Similarly, debates over voting rights become political when certain groups use their power to restrict access to the ballot, highlighting how the control of political processes themselves is a manifestation of power dynamics. In these cases, the issue is no longer just about the policy itself but about who holds the power to shape outcomes.

The exercise of power also makes an issue political when it involves coercion, exclusion, or the imposition of one group’s values on another. For example, laws regulating reproductive rights are deeply political because they reflect the power of certain ideological or religious groups to control women’s bodies. The act of legislating personal choices becomes political when it is driven by the desire to maintain or alter power structures. Similarly, environmental policies become political when corporations use their economic power to influence regulations, pitting profit motives against public welfare. The politicization arises from the conflict between different power holders and their competing interests.

Furthermore, an issue becomes political when it challenges or seeks to redistribute power. Movements for social justice, such as those advocating for racial equality or LGBTQ+ rights, are inherently political because they aim to dismantle existing power structures and create more equitable distributions of power. These movements politicize issues by framing them as struggles against oppression and domination. For instance, the fight for civil rights in the 1960s was political because it directly confronted the power of segregationist institutions and sought to redistribute political and social power to marginalized communities. The very act of challenging power dynamics ensures that the issue remains firmly within the political sphere.

Lastly, the perception of power and its legitimacy can politicize an issue. When decisions are seen as favoring certain groups at the expense of others, they become political, even if the intent was neutral. For example, urban development projects often become political when residents perceive them as benefiting wealthy investors more than local communities. The politics of perception underscores how power dynamics are not just about the reality of power but also about how it is experienced and interpreted by those involved. In this way, the distribution and exercise of power are central to understanding when and why something becomes political.

Does Indiana Require Political Party Registration? Understanding the Legal Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Public vs. Private: At what point do private matters enter the political sphere?

The distinction between public and private matters is a complex and often blurred line, especially when considering what constitutes a political issue. Private matters, by definition, pertain to individuals' personal lives, choices, and affairs, typically shielded from public scrutiny and government intervention. However, certain private issues can transcend this boundary and become political when they intersect with broader societal concerns, public policy, or collective rights. This transformation occurs when private decisions or circumstances impact the wider community, challenge established norms, or require regulatory oversight to ensure fairness and justice.

One critical point at which private matters enter the political sphere is when they involve systemic inequalities or injustices. For example, personal experiences of discrimination based on race, gender, or sexual orientation may initially seem private, but when they reflect widespread patterns of oppression, they become political. Movements like #MeToo or Black Lives Matter illustrate how individual stories of harassment or police brutality, when aggregated, expose systemic issues that demand political action, policy changes, and legal reforms. In these cases, the private becomes political because addressing these issues requires collective solutions and governmental intervention.

Another instance where private matters become political is when individual choices have public consequences or require public resources. For instance, healthcare decisions, such as vaccination or reproductive rights, are often considered private. However, they enter the political realm when they affect public health, healthcare systems, or societal norms. Debates over abortion rights or vaccine mandates highlight how personal choices can become politicized when they intersect with public policy, ethical frameworks, and the allocation of resources. The political dimension arises because these decisions impact not just the individual but also the community at large.

Private matters also become political when they challenge or reinforce existing power structures. Wealth inequality, for example, is often viewed as a private issue tied to individual success or failure. However, when extreme disparities in wealth undermine social mobility, exacerbate poverty, or influence political systems through lobbying and campaign financing, it becomes a political problem. Similarly, issues like inheritance laws or tax policies, which directly affect private wealth, are inherently political because they shape economic opportunities and societal fairness. Here, the private enters the political sphere due to its implications for power dynamics and social equity.

Lastly, private matters can become political when they involve fundamental rights and freedoms. Personal beliefs, religious practices, or lifestyle choices are typically private, but they gain political significance when they are threatened, restricted, or used to justify discrimination. For example, debates over same-sex marriage or religious freedom laws demonstrate how private convictions become political when they intersect with legal rights, equality, and the role of government in protecting or limiting individual freedoms. The political dimension emerges because these issues require balancing individual liberties with collective values and legal frameworks.

In conclusion, private matters enter the political sphere when they intersect with systemic issues, public consequences, power structures, or fundamental rights. This transformation is not automatic but depends on the context, impact, and societal implications of the issue at hand. Understanding this boundary is crucial for navigating the relationship between individual autonomy and collective responsibility, as well as for addressing the challenges of governance in an increasingly interconnected world.

Greek Theatre's Political Power: Shaping Democracy Through Performance

You may want to see also

Collective Action: When does group behavior or advocacy transform into a political movement?

Collective action, at its core, involves individuals coming together to achieve a common goal, often through coordinated efforts like protests, campaigns, or community organizing. However, not all collective action is inherently political. For group behavior or advocacy to transform into a political movement, it must engage with or challenge the structures of power, governance, or public policy. This transformation occurs when the collective action explicitly seeks to influence decision-making processes, reshape societal norms, or redistribute resources in a way that impacts the broader political landscape. For instance, a group advocating for cleaner parks in a neighborhood may start as a community initiative but becomes political when it demands policy changes or funding reallocation from local authorities.

The shift from advocacy to a political movement often hinges on the scale and scope of the group's objectives. When a collective action moves beyond localized, individual concerns and begins to address systemic issues, it enters the political realm. For example, a labor union fighting for better wages at a single factory is engaging in collective action, but when it advocates for nationwide labor laws or challenges corporate influence on government policies, it becomes a political movement. This escalation is marked by the group's recognition that their grievances are symptomatic of larger political or economic systems that require structural change.

Another critical factor is the group's interaction with formal political institutions. Collective action transforms into a political movement when it directly engages with government bodies, political parties, or international organizations. This can involve lobbying, drafting legislation, or participating in electoral processes. For instance, the civil rights movement in the United States began as localized protests and advocacy but became a full-fledged political movement by pushing for federal legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This engagement with the political system underscores the movement's intent to effect change through established power structures.

The framing and rhetoric of the collective action also play a significant role in its politicization. When a group articulates its demands in terms of justice, equality, or rights—concepts deeply embedded in political discourse—it signals a political dimension. For example, climate activism often transitions from environmental advocacy to a political movement by framing ecological issues as matters of intergenerational justice, economic policy, or global governance. This reframing broadens the appeal and relevance of the cause, mobilizing diverse stakeholders and positioning it within the political agenda.

Finally, the response from those in power can catalyze the transformation of collective action into a political movement. When authorities label a group's activities as subversive, regulate their actions, or attempt to suppress them, it often politicizes the cause. This dynamic was evident in the #MeToo movement, which began as individual stories of harassment but became a political force as it challenged institutional power dynamics and demanded legislative reforms. The very act of being treated as a political threat can solidify a group's identity as a movement with political aspirations.

In summary, collective action evolves into a political movement when it targets systemic change, engages with formal political institutions, adopts political framing, and confronts or is confronted by established power structures. This transformation is not merely about the size or visibility of the group but about its intentionality in reshaping the political and social order. Understanding this transition is crucial for recognizing when advocacy crosses the threshold into the realm of politics, where the stakes are higher, and the potential for impact is far-reaching.

Exploring Zimbabwe's Political Landscape: Do Political Parties Exist There?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not necessarily. Something is considered political when it involves power dynamics, resource allocation, or decision-making processes that affect a group or society, even if it doesn't directly involve government.

Yes, personal choices can be political if they reflect or challenge societal norms, power structures, or systemic issues. For example, choosing to boycott a product for ethical reasons is a political act.

Yes, art and entertainment can be political when they address social, cultural, or systemic issues, critique power structures, or advocate for change. Even if not explicitly intended, they can still carry political implications.