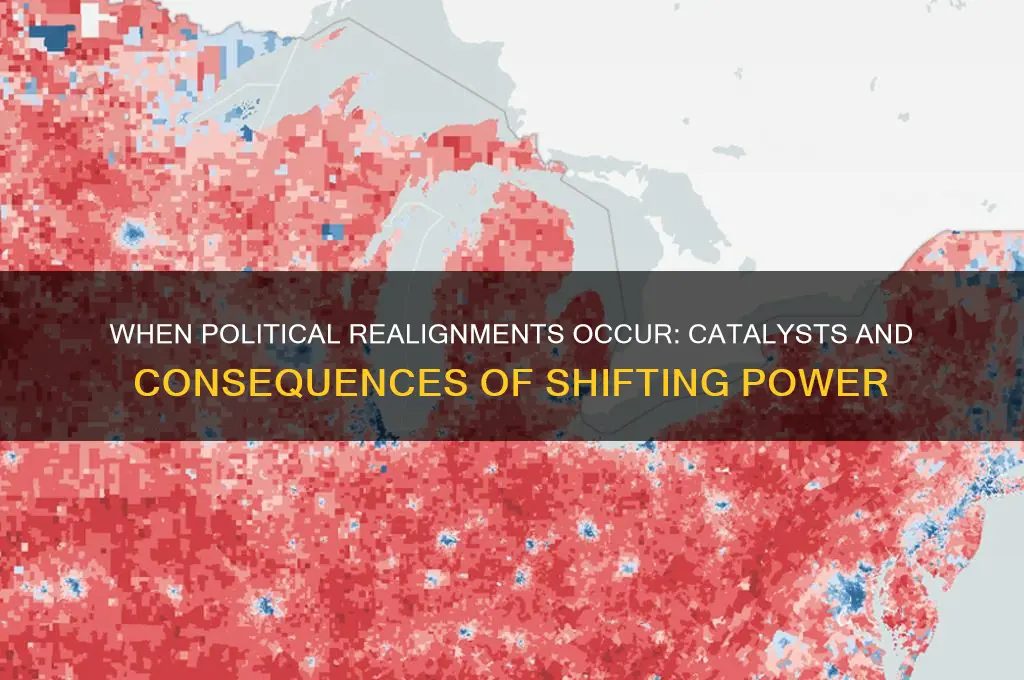

Political realignments occur when there is a significant and lasting shift in the electoral and ideological landscape of a political system, often marked by the emergence of new coalitions, the decline of old ones, and a reconfiguration of party identities. These shifts are typically driven by major societal changes, such as economic crises, cultural transformations, or technological advancements, which challenge existing political norms and force parties to adapt or risk obsolescence. Realignments are not merely temporary fluctuations in voting patterns but rather fundamental realignments of power that reshape the balance between political parties and redefine the issues that dominate public discourse. Historically, they have been associated with pivotal moments such as the Great Depression, civil rights movements, or global conflicts, which create new cleavages and priorities among voters. Understanding when and why these realignments occur is crucial for analyzing the dynamics of political systems and predicting future shifts in power.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Major Social or Economic Changes | Occur during significant shifts like industrialization, urbanization, or globalization. Example: Post-WWII economic boom reshaping party coalitions. |

| Critical Elections | Elections that mark a lasting shift in voter behavior and party dominance. Example: 1896 U.S. election solidifying GOP dominance. |

| New Issue Emergence | New issues (e.g., civil rights, climate change) polarize voters and realign party platforms. Example: 1960s civil rights movement splitting the Democratic Party. |

| Party System Collapse | Existing parties fail to address new demands, leading to realignment. Example: Whig Party collapse in the 1850s over slavery. |

| Technological Advancements | Innovations like social media or mass media reshape political communication and voter engagement. Example: 2008 Obama campaign leveraging digital tools. |

| Demographic Shifts | Changes in population (e.g., immigration, generational turnover) alter electoral landscapes. Example: Growing Latino population influencing U.S. politics since 2000. |

| External Shocks | Crises like wars, pandemics, or economic depressions accelerate realignment. Example: Great Depression leading to New Deal coalition. |

| Ideological Polarization | Increasing ideological divides between parties and voters. Example: 21st-century polarization in U.S. politics. |

| Leadership and Charisma | Transformative leaders (e.g., FDR, Reagan) redefine party identities. Example: Reagan's conservative revolution in the 1980s. |

| Institutional Changes | Reforms like voting rights expansions or campaign finance laws impact realignment. Example: Voting Rights Act of 1965 empowering minority voters. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic crises trigger shifts in voter priorities, leading to political realignments and new party dominance

- Social movements reshape public opinion, forcing parties to adapt or lose support

- Wars and conflicts often redefine national identities, causing political alliances to realign

- Technological advancements disrupt industries, altering voter demographics and political loyalties

- Demographic changes, like aging populations, push parties to redefine their platforms

Economic crises trigger shifts in voter priorities, leading to political realignments and new party dominance

Economic crises have historically been powerful catalysts for political realignments, as they fundamentally alter voter priorities and reshape the political landscape. When economies collapse, such as during the Great Depression of the 1930s or the 2008 global financial crisis, voters often lose faith in the incumbent party’s ability to manage the economy effectively. This disillusionment creates an opening for opposition parties to offer alternative solutions, often centered on new economic policies or ideologies. For instance, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the United States marked a significant realignment, as voters shifted their allegiance to the Democratic Party, which promised government intervention and social welfare programs to address the crisis. This shift not only changed party dominance but also redefined the role of government in the economy for decades.

During economic crises, voter priorities tend to pivot toward immediate concerns like job security, income stability, and social safety nets. Parties that successfully address these issues through compelling narratives and policy proposals gain a competitive edge. For example, in Europe following the 2008 financial crisis, populist and anti-austerity movements gained traction as traditional parties were perceived as failing to protect citizens from economic hardship. This led to realignments in countries like Greece and Italy, where new parties or coalitions rose to power by promising to challenge the status quo and prioritize domestic economic interests over global financial demands.

Economic crises also expose and exacerbate existing inequalities, further driving political realignments. Voters from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who are often disproportionately affected by economic downturns, may seek out parties that advocate for redistribution, labor rights, or protectionist policies. Conversely, wealthier voters might align with parties promising fiscal discipline or free-market solutions. This polarization of voter priorities can lead to the decline of centrist parties and the rise of more ideologically distinct alternatives, as seen in the United Kingdom during the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, where both the Conservative Party and the Labour Party underwent internal shifts to appeal to new voter blocs.

The duration and severity of an economic crisis play a critical role in determining the extent of political realignment. Short-lived recessions may result in temporary shifts in voter behavior, while prolonged crises often lead to more enduring changes in party dominance. For instance, the stagflation of the 1970s in the United States eroded support for the Democratic Party, paving the way for Ronald Reagan’s conservative revolution in the 1980s. Similarly, the eurozone crisis in the 2010s led to prolonged realignments in several European countries, as voters sought alternatives to the austerity measures imposed by incumbent governments.

Finally, economic crises often force parties to reinvent themselves or give rise to entirely new political movements. Established parties may adopt new platforms to remain relevant, while outsider candidates or parties can capitalize on public discontent to challenge the political establishment. The Occupy Wall Street movement in the U.S. and the rise of left-wing parties in Southern Europe during the 2010s are examples of how economic crises can catalyze the emergence of new political forces. These shifts in party systems and voter alignments underscore the transformative impact of economic crises on the political order, often leading to new eras of party dominance and governance.

The Dark Side of Democracy: Why Political News Focuses on Negativity

You may want to see also

Social movements reshape public opinion, forcing parties to adapt or lose support

Social movements play a pivotal role in reshaping public opinion by amplifying marginalized voices, challenging established norms, and redefining societal priorities. When issues like civil rights, gender equality, or environmental justice gain momentum through grassroots organizing, they often shift the Overton window—the range of policies considered politically acceptable. For instance, the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s transformed public attitudes toward racial equality, forcing political parties to address systemic racism or risk alienating a growing coalition of voters. This dynamic illustrates how social movements act as catalysts for political realignment by creating new fault lines in public opinion that parties must navigate.

As social movements gain traction, they often expose the limitations of existing party platforms, compelling parties to adapt or face electoral consequences. Parties that fail to respond to shifting public sentiment risk losing support to more agile competitors or new political formations. For example, the rise of the LGBTQ+ rights movement in the 21st century pushed many center-left parties to embrace marriage equality, while those that resisted found themselves out of step with a significant portion of their base. This adaptive process is not merely about policy shifts but also about signaling to voters that a party is responsive to their evolving concerns, a critical factor in maintaining relevance during periods of realignment.

The pressure exerted by social movements often leads to intra-party conflicts, as factions within parties debate how to respond to changing public opinion. Progressive wings may push for bold reforms, while more conservative elements resist change, creating internal tensions that can fracture party unity. This was evident in the Democratic Party during the 1960s, when its Southern conservative base clashed with Northern liberals over civil rights legislation. Such divisions can weaken a party's electoral prospects, opening the door for realignment as voters seek alternatives that better align with their values.

Social movements also reshape public opinion by framing issues in ways that resonate emotionally and morally, making it difficult for parties to ignore them. For instance, the Black Lives Matter movement reframed police brutality as a systemic issue of racial injustice, galvanizing public support and forcing politicians across the spectrum to address the topic. Parties that fail to engage with these frames risk appearing tone-deaf or out of touch, while those that embrace them can tap into powerful currents of public sentiment. This framing power is a key mechanism through which social movements drive political realignment.

Finally, social movements often create new coalitions of voters by mobilizing previously disengaged or marginalized groups. These coalitions can realign the electoral landscape by shifting the balance of power between parties. For example, the women's suffrage movement not only secured voting rights for women but also reshaped the political terrain, as women became a critical voting bloc that parties had to court. In this way, social movements not only reshape public opinion but also reconfigure the demographic and ideological bases of political parties, making realignment inevitable.

Polarization's Peril: How Divisive Politics Threatens Democracy and Society

You may want to see also

Wars and conflicts often redefine national identities, causing political alliances to realign

Wars and conflicts have historically been catalysts for profound political realignments, as they force nations to reevaluate their identities, priorities, and alliances. When a country is thrust into conflict, its citizens often experience a heightened sense of unity or division, depending on how the war is perceived and managed. This redefinition of national identity can lead to significant shifts in political landscapes. For instance, World War I reshaped the political map of Europe, leading to the collapse of empires and the rise of new nation-states. The war's aftermath saw the emergence of nationalist movements and the realignment of political parties around issues of sovereignty and self-determination, fundamentally altering the balance of power on the continent.

Conflicts often expose or exacerbate existing social and political fault lines, pushing nations to confront questions of who belongs and what values define them. During wartime, governments may adopt policies that either unite or polarize their populations, depending on how they frame the conflict. For example, the Vietnam War in the United States led to a deep political realignment as it divided the nation along ideological lines, reshaping the Democratic and Republican parties. Anti-war sentiments and civil rights movements pushed the Democratic Party toward more progressive stances, while the Republican Party capitalized on nationalist and conservative sentiments. This realignment had lasting effects on American politics, influencing party platforms and voter demographics for decades.

Wars also redefine international alliances, as nations seek new partners or distance themselves from former allies based on shared or conflicting interests. The Cold War is a prime example of how global conflicts can lead to political realignments on a massive scale. Countries around the world were forced to choose sides between the United States and the Soviet Union, leading to the formation of NATO and the Warsaw Pact. These alliances not only shaped international relations but also influenced domestic politics within member states, as governments aligned their policies with the broader goals of their respective blocs. The end of the Cold War further demonstrated how the resolution of a conflict can trigger realignment, as former adversaries sought new partnerships and redefined their national identities in a post-bipolar world.

Moreover, wars often accelerate social and economic changes that contribute to political realignment. For instance, World War II led to the decolonization of many nations, as the war weakened European powers and emboldened independence movements. This global shift in power dynamics forced political parties and leaders to adapt to new realities, often leading to the rise of socialist, nationalist, or liberal movements in newly independent countries. Similarly, the economic strain of war can lead to the rise of populist or extremist political forces, as seen in post-World War I Europe, where economic instability and national humiliation contributed to the ascent of fascist regimes.

In summary, wars and conflicts act as powerful agents of political realignment by redefining national identities and reshaping alliances. They force societies to confront existential questions, expose internal divisions, and alter international power structures. Whether through the rise of new ideologies, the formation of global blocs, or the acceleration of social change, conflicts leave indelible marks on political landscapes. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for comprehending how and when political realignments occur, as they are often rooted in the transformative power of war and its aftermath.

The Intricate Dance: Why Policy Making is Inherently Political

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Technological advancements disrupt industries, altering voter demographics and political loyalties

Technological advancements have become a significant catalyst for political realignments by fundamentally disrupting industries, reshaping labor markets, and altering voter demographics. When new technologies emerge—such as automation, artificial intelligence, or the internet—they often displace traditional jobs while creating new ones. This shift can lead to economic displacement in certain regions or sectors, causing voters to reevaluate their political loyalties. For example, the decline of manufacturing jobs due to automation has eroded the traditional working-class base of some political parties, pushing these voters toward alternatives that promise economic protection or change. Conversely, tech-driven industries like renewable energy or software development may foster new voter blocs with distinct political priorities, such as innovation-friendly policies or environmental sustainability.

The geographic concentration of tech-driven industries further exacerbates these shifts, leading to demographic and political changes. Cities and regions that become hubs for technology companies experience population growth, attracting younger, more educated, and often more progressive voters. This demographic influx can tilt traditionally conservative areas toward liberalism or vice versa, depending on the political leanings of the incoming population. For instance, the rise of Silicon Valley and other tech corridors has transformed once-conservative suburban areas into Democratic strongholds, as tech workers tend to favor policies like immigration reform, education funding, and social liberalism.

Technological advancements also reshape communication and information dissemination, which directly impacts political loyalties. Social media platforms, for instance, have democratized access to information but also enabled the spread of misinformation, polarizing electorates. Voters exposed to diverse viewpoints online may shift their allegiances, while others may double down on existing beliefs. Additionally, digital campaigns and targeted advertising allow political parties to mobilize new constituencies, often appealing to younger, tech-savvy voters who prioritize issues like digital privacy, net neutrality, or climate change. This reconfiguration of political messaging and outreach can accelerate realignments by aligning parties with emerging voter concerns.

The economic inequality exacerbated by technological disruption further fuels political realignments. As tech industries concentrate wealth in fewer hands, income disparities widen, creating resentment among those left behind. This dynamic can lead to the rise of populist movements or parties that capitalize on economic anxieties. For example, automation-driven job losses in Rust Belt regions have been linked to the rise of populist rhetoric and shifts in voting patterns. Simultaneously, affluent tech elites may advocate for policies like universal basic income or corporate regulation, pushing mainstream parties to adopt more progressive or libertarian platforms to retain their support.

Finally, technological advancements create new policy challenges that force political parties to adapt or risk obsolescence. Issues like data privacy, cybersecurity, and the ethical use of AI were once niche concerns but have now become central to political debates. Parties that fail to address these issues risk losing relevance, while those that embrace them can attract voters who prioritize technological governance. This adaptation often leads to realignments, as parties realign their platforms to reflect the realities of a tech-driven world, shedding old ideologies in favor of new ones that resonate with evolving voter demographics. In this way, technology not only disrupts industries but also reshapes the political landscape, driving realignments that redefine the balance of power.

Hitler's Political Rise: Unraveling the Motives Behind His Entry into Politics

You may want to see also

Demographic changes, like aging populations, push parties to redefine their platforms

Demographic changes, particularly the aging of populations, serve as a significant catalyst for political realignments by forcing political parties to reassess and redefine their platforms. As societies age, the priorities and needs of the electorate shift, compelling parties to adapt their policies to remain relevant. Aging populations typically demand greater emphasis on healthcare, pensions, and social security, while issues like education and job creation may take a backseat. Parties that fail to address these new priorities risk losing support, while those that successfully pivot can solidify their appeal to a changing demographic. This dynamic often leads to a realignment of political loyalties, as traditional party bases erode and new coalitions emerge.

The aging population also influences the ideological positioning of parties. For instance, older voters tend to be more conservative on fiscal issues, favoring balanced budgets and lower taxes, while being more liberal on social welfare programs that directly benefit them. This creates a tension within parties, particularly those with historically broad coalitions, as they must balance the interests of younger, more progressive voters with the demands of older, more conservative constituents. Parties that can navigate this tension by crafting nuanced policies that appeal to both groups are more likely to thrive, while those that alienate one demographic in favor of another may face fragmentation and decline.

Moreover, the aging of populations often intersects with other demographic trends, such as urbanization and immigration, further complicating the political landscape. In many countries, older voters are concentrated in rural areas, while younger voters dominate urban centers. This geographic divide can exacerbate political polarization, as parties become increasingly associated with specific regions or demographic groups. To counteract this, parties may need to adopt more localized or targeted platforms, addressing the unique concerns of aging populations in rural areas while also appealing to younger, urban voters. This strategic redefinition of party platforms is a hallmark of political realignment driven by demographic shifts.

Another critical aspect of demographic-driven realignment is the role of intergenerational equity. As aging populations place greater strain on public resources, younger voters may feel increasingly marginalized by policies that prioritize the elderly. This can lead to the rise of new political movements or parties that champion the interests of younger generations, challenging established parties to reconsider their priorities. In response, traditional parties may adopt policies aimed at fostering intergenerational solidarity, such as investments in education, affordable housing, and climate action, which appeal to younger voters while still addressing the needs of the elderly.

Ultimately, demographic changes like aging populations force political parties to engage in a process of continuous adaptation and reinvention. Parties that successfully redefine their platforms to reflect the evolving needs and values of the electorate are more likely to survive and thrive in a changing political landscape. Conversely, those that cling to outdated policies or fail to recognize the shifting demographic realities risk becoming obsolete. This dynamic underscores the importance of demographic trends in driving political realignments, as parties must constantly recalibrate their strategies to maintain relevance in an increasingly diverse and aging society.

Do Political Parties Own Issues? Exploring the Monopoly on Policy Narratives

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political realignments are typically triggered by major societal shifts, such as economic crises, wars, social movements, or significant changes in demographics and values. These events create new political cleavages and reshape voter coalitions.

Political realignments are rare and occur approximately every 30 to 50 years. They are distinct from regular election cycles and represent fundamental, lasting changes in the political landscape.

Key indicators include a shift in dominant political parties, the emergence of new issues or ideologies, significant changes in voter behavior, and the realignment of geographic or demographic groups with specific parties.

A single election rarely signifies a realignment. Instead, realignments are confirmed by consistent patterns across multiple elections, demonstrating sustained changes in party dominance and voter loyalties.

![Election (The Criterion Collection) [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71KtYtmztoL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![ELECTION - PARAMOUNT PRESENTS Volume 46 [4K UHD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61L7W9FV2nL._AC_UL320_.jpg)