Political protest, as a form of collective expression against perceived injustices or oppressive systems, has roots that stretch back to the earliest recorded civilizations. While the specific forms and motivations have evolved, the essence of protest can be traced to ancient societies where individuals or groups challenged authority, often in response to economic exploitation, social inequality, or political tyranny. One of the earliest documented instances is the strike by Egyptian tomb builders in the 12th century BCE, who protested unpaid wages under Pharaoh Ramses III. Similarly, ancient Greece and Rome witnessed public demonstrations and riots against rulers or policies deemed unfair. These early acts of dissent laid the groundwork for the more structured and ideologically driven protests that emerged in later centuries, particularly during the Enlightenment and the rise of modern nation-states. Thus, political protest is not a modern invention but a timeless human response to power imbalances and the quest for justice.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Earliest Recorded Protests | Ancient civilizations (e.g., Egypt, Rome, Greece) around 2000 BCE to 500 BCE |

| Notable Early Examples | Egyptian workers' strike during the reign of Ramses III (12th century BCE) |

| Medieval Period | Peasant revolts in Europe (e.g., Peasants' Revolt in England, 1381) |

| Renaissance and Reformation | Religious and political uprisings (e.g., German Peasants' War, 1524–1525) |

| 17th Century | English Civil War (1642–1651), Levellers' movement for political rights |

| 18th Century | American Revolution (1765–1783), French Revolution (1789–1799) |

| 19th Century | Labor movements, Chartist movement in the UK, abolitionist protests |

| 20th Century | Civil rights movements, anti-war protests (e.g., Vietnam War), global uprisings |

| 21st Century | Arab Spring (2010–2012), Black Lives Matter, climate strikes (e.g., Fridays for Future) |

| Common Themes | Resistance to oppression, demands for rights, economic grievances |

| Methods | Strikes, marches, petitions, civil disobedience, digital activism |

| Global Spread | Protests have occurred across continents, often inspired by shared ideals |

| Impact | Led to political reforms, regime changes, and shifts in societal norms |

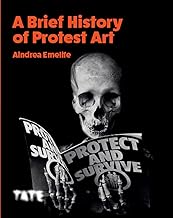

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ancient Civilizations: Early protests against rulers in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome

- Medieval Rebellions: Peasant uprisings, such as the Peasants' Revolt in 14th-century England

- Enlightenment Era: Protests inspired by ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy in the 18th century

- Industrial Revolution: Worker protests against poor conditions and exploitation in the 19th century

- Modern Movements: 20th-century protests for civil rights, anti-war, and environmental causes

Ancient Civilizations: Early protests against rulers in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome

The roots of political protest can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where early forms of dissent against rulers emerged in response to oppression, exploitation, and injustice. In Mesopotamia, one of the earliest cradles of civilization, protests took shape as collective actions by laborers and citizens against their rulers. The Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) provides indirect evidence of social unrest, as it includes provisions to address grievances such as debt slavery and unfair labor practices. Workers in temples and palaces occasionally staged strikes or revolts, refusing to work until their demands for better treatment or relief from excessive taxes were met. These actions, though not always documented in detail, demonstrate that even in ancient societies, people sought to challenge authority when their basic needs were ignored.

In ancient Egypt, protests were less frequent due to the highly centralized and divine authority of the pharaohs, but instances of resistance still occurred. During periods of economic hardship or oppressive rule, such as the reign of Pharaoh Pepi II (2278–2184 BCE), there are records of civil unrest and labor strikes. Workers building royal tombs in Deir el-Medina, for example, went on strike during the New Kingdom (circa 13th century BCE) to demand better living conditions and payment. These actions, though localized, highlight the universal human impulse to resist exploitation, even in a society where the ruler was considered a god.

Ancient Greece saw more formalized expressions of political protest, particularly in city-states like Athens, where democratic principles began to take root. Citizens could voice their grievances through public assemblies, and philosophers like Socrates and Aristotle debated the nature of justice and governance. However, even in oligarchic or tyrannical regimes, protests occurred. For instance, the Athenian tyrant Peisistratus faced opposition from rival factions, and his rule was marked by periodic uprisings. The concept of *isonomia* (equality under the law) inspired citizens to challenge leaders who abused their power, laying the groundwork for later democratic movements.

In ancient Rome, protests took various forms, from plebeian uprisings to organized strikes. The Conflict of the Orders (5th century BCE) was a prolonged struggle between the patrician elite and the plebeian class, culminating in the establishment of the Twelve Tables, Rome's first written law code. Later, during the Republic and Empire, citizens and slaves alike staged protests against taxation, corruption, and oppressive rulers. The famous revolt of Spartacus (73–71 BCE) was a large-scale slave rebellion against Roman authority, though it was ultimately crushed. These events demonstrate that even in a highly militarized society, marginalized groups sought to challenge the status quo and demand justice.

Across these ancient civilizations, protests were often driven by economic hardship, oppressive governance, or the denial of basic rights. While the methods and outcomes varied, the underlying motivation was consistent: to resist authority that threatened the well-being of individuals or communities. These early forms of dissent laid the foundation for the concept of political protest, showing that the struggle for justice and equality is as old as civilization itself.

Can Fresh Faces Revitalize the Democratic Party's Future?

You may want to see also

Medieval Rebellions: Peasant uprisings, such as the Peasants' Revolt in 14th-century England

The roots of political protest can be traced back to ancient civilizations, but medieval rebellions, particularly peasant uprisings, mark a significant chapter in the history of collective dissent. Among these, the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 in 14th-century England stands as one of the most notable examples. This uprising was a direct response to the socio-economic and political oppression faced by the lower classes under the feudal system. The revolt was sparked by the introduction of the third poll tax in 15 years, which disproportionately burdened the peasantry. Led by figures like Wat Tyler and John Ball, the rebels demanded an end to serfdom, lower rents, and the abolition of the poll tax. Their actions were not merely spontaneous but were fueled by long-standing grievances and a growing awareness of social injustice.

The Peasants' Revolt was characterized by its organized nature and the radical ideas it espoused. John Ball, a radical priest, famously questioned the divine right of the nobility with his sermon asking, "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?" This rhetoric challenged the hierarchical structure of medieval society and inspired thousands to march on London. The rebels targeted symbols of authority, burning court records and attacking the homes of tax collectors and nobles. Their demands, though ultimately suppressed, reflected a nascent form of political consciousness among the lower classes, demonstrating that even in the rigid feudal system, the oppressed could mobilize against their exploiters.

Peasant uprisings were not unique to England; they occurred across medieval Europe as a response to similar conditions. For instance, the Jacquerie in France (1358) and the Ciompi Revolt in Florence (1378) were both driven by economic exploitation and the desire for greater rights. These rebellions often arose during periods of crisis, such as famines, plagues, or heavy taxation, which exacerbated the plight of the peasantry. While most of these uprisings were brutally suppressed, they underscored the fragility of feudal authority and the potential for collective action to challenge established power structures.

The medieval peasant uprisings also highlight the role of communication and leadership in organizing political protest. Rebels often used networks of villages, churches, and markets to spread their message and coordinate actions. Leaders like Wat Tyler emerged from within the peasant ranks, demonstrating that even in a society with limited literacy and mobility, individuals could inspire and mobilize large groups. These movements, though often short-lived, laid the groundwork for future protests by demonstrating the power of collective action and the possibility of challenging unjust systems.

In conclusion, medieval rebellions, particularly peasant uprisings like the Peasants' Revolt, represent an early form of political protest rooted in resistance to oppression and exploitation. These movements, while often crushed, revealed the capacity of the lower classes to organize and demand change. They also marked a shift in the perception of authority, as rebels began to question the legitimacy of the feudal order. By studying these uprisings, we gain insight into the origins of political dissent and the enduring human desire for justice and equality.

Political Parties: Essential for Governance or Hindrance to Progress?

You may want to see also

Enlightenment Era: Protests inspired by ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy in the 18th century

The Enlightenment Era, spanning the 18th century, marked a pivotal moment in the history of political protest, as the ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy began to challenge the established monarchies and feudal systems of Europe. This intellectual movement, driven by philosophers like John Locke, Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, laid the groundwork for a new understanding of individual rights and governance. Their writings emphasized the importance of reason, natural rights, and the social contract, inspiring ordinary people to question authority and demand political change. These ideas did not remain confined to scholarly circles; they permeated public discourse, fueling discontent among the masses and setting the stage for organized protests.

One of the most significant manifestations of Enlightenment-inspired protests was the American Revolution (1765–1783). Colonists in British North America, influenced by Enlightenment ideals, began to resist what they saw as unjust taxation and tyranny by the British Crown. Protests such as the Boston Tea Party in 1773 symbolized the growing defiance against colonial rule. Pamphlets like Thomas Paine’s *Common Sense* (1776) further galvanized public opinion, arguing for independence and self-governance based on Enlightenment principles. The Declaration of Independence in 1776 explicitly echoed these ideas, asserting that "all men are created equal" and endowed with unalienable rights to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." This revolution not only established the United States as an independent nation but also demonstrated the power of Enlightenment ideals to mobilize populations against oppression.

Across the Atlantic, the French Revolution (1789–1799) stands as another monumental example of Enlightenment-inspired protest. The storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, was a direct response to the economic and political inequalities of the Ancien Régime. Influenced by Rousseau’s concept of the general will and Montesquieu’s advocacy for the separation of powers, the French people demanded an end to absolute monarchy and the establishment of a republic. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789) codified Enlightenment principles, proclaiming equality before the law and the sovereignty of the people. Mass protests, such as the Women’s March on Versailles in 1789, highlighted the role of ordinary citizens, including women, in driving revolutionary change.

The Enlightenment also inspired protests beyond Europe and North America. In Haiti, the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) was fueled by Enlightenment ideals of liberty and equality, as enslaved Africans and free people of color rose up against French colonial rule. Leaders like Toussaint Louverture drew upon Enlightenment philosophy to justify their struggle for freedom and independence. This revolution not only abolished slavery in Haiti but also sent shockwaves across the Atlantic world, challenging the institution of slavery and colonial domination.

In conclusion, the Enlightenment Era played a transformative role in the history of political protest by providing a philosophical framework for challenging authority and demanding rights. Protests during this period were not merely reactions to immediate grievances but were deeply rooted in the ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy. From the American and French Revolutions to the Haitian struggle for freedom, the 18th century demonstrated the power of Enlightenment ideals to inspire mass movements and reshape political systems. These protests laid the foundation for modern democratic principles and continue to influence political activism to this day.

Key Roles of Political Parties: Five Essential Functions Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Industrial Revolution: Worker protests against poor conditions and exploitation in the 19th century

The Industrial Revolution, which began in the late 18th century and accelerated throughout the 19th century, brought about profound economic and social changes. While it spurred technological advancements and increased productivity, it also led to widespread exploitation and poor working conditions for the burgeoning working class. Factories, mines, and mills became the epicenters of labor, where workers, including women and children, endured long hours, hazardous environments, and meager wages. This stark disparity between industrial profits and worker welfare ignited a wave of protests that marked a significant chapter in the history of political dissent.

Worker protests during the Industrial Revolution were often spontaneous and localized, driven by immediate grievances such as wage cuts, unsafe conditions, or excessive working hours. One of the earliest and most notable examples was the Luddite movement in England (1811–1816). Skilled textile workers, known as Luddites, protested against the introduction of machinery that threatened their livelihoods. They sabotaged factories and destroyed machines, demanding better conditions and job security. Although the movement was suppressed by the government, it highlighted the growing tension between technological progress and worker rights.

As industrialization spread across Europe and North America, protests became more organized and politically charged. The Chartist movement in Britain (1838–1848) was a landmark in worker activism, advocating for political reforms to address economic exploitation. Chartists demanded universal suffrage, fair wages, and improved working conditions through petitions and mass rallies. Although their immediate goals were not fully realized, the movement laid the groundwork for future labor rights campaigns and demonstrated the power of collective action.

In the United States, the 1830s and 1840s saw a surge in worker protests, particularly in response to the rise of factories and the decline of artisanal labor. The Lowell Mill Girls in Massachusetts, for instance, organized strikes and petitions to protest low wages and harsh working conditions in textile mills. Their efforts, though met with resistance, inspired broader labor movements and underscored the importance of solidarity among workers. Similarly, the 10-Hour Movement gained momentum as workers demanded a reduction in the standard workday from 12 to 10 hours, culminating in legislative changes in several states.

The mid-to-late 19th century witnessed the rise of trade unions and international labor organizations, which formalized worker protests into sustained campaigns for rights and protections. The Paris Commune of 1871 stands as a radical example of worker uprising, where laborers seized control of the city to demand social and economic reforms. Although short-lived, it symbolized the growing militancy of the working class in the face of exploitation. These protests were not merely reactions to immediate hardships but also reflected a broader struggle for dignity, fairness, and political representation in an era of rapid industrialization.

In conclusion, the Industrial Revolution catalyzed worker protests that challenged the exploitative practices of the time and laid the foundation for modern labor rights movements. From the Luddites to the Chartists, and from the Lowell Mill Girls to the Paris Commune, these protests were pivotal in shaping the discourse on economic justice and political participation. They demonstrated that political protest is not only a response to oppression but also a force for systemic change, echoing through history as a testament to the resilience and solidarity of the working class.

The Largest Political Party in the US: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

Modern Movements: 20th-century protests for civil rights, anti-war, and environmental causes

The 20th century witnessed a surge in political protests, marking a pivotal era in the evolution of modern movements advocating for civil rights, peace, and environmental preservation. These protests were characterized by their global reach, diverse methodologies, and profound impact on societal and political structures. One of the most influential movements was the Civil Rights Movement in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. Led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr., this movement employed nonviolent resistance, including marches, boycotts, and sit-ins, to challenge racial segregation and discrimination. The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–1956) and the March on Washington (1963) were landmark events that galvanized public support and led to significant legislative changes, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Simultaneously, the anti-war movement gained momentum, particularly in response to the Vietnam War. Protests against the war began in the early 1960s and escalated as the conflict intensified. The movement was global, with demonstrations occurring in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Iconic moments included the 1967 March on the Pentagon and the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests in Chicago. Activists like Jane Fonda and organizations such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) played crucial roles in mobilizing opposition. The anti-war movement not only criticized the war itself but also questioned the broader policies of militarism and imperialism, influencing public opinion and contributing to the eventual withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam.

The environmental movement also emerged as a significant force in the 20th century, driven by growing concerns about pollution, deforestation, and resource depletion. The publication of Rachel Carson's *Silent Spring* in 1962 is often cited as a catalyst for modern environmentalism. Protests and advocacy efforts led to the establishment of Earth Day in 1970, which mobilized millions of people worldwide. Environmental organizations like Greenpeace and the Sierra Club gained prominence, advocating for policies to protect natural habitats and combat climate change. The movement’s successes include the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the U.S. and international agreements like the Kyoto Protocol.

These modern movements were interconnected, often drawing inspiration and tactics from one another. For instance, the civil rights movement's emphasis on nonviolent resistance influenced anti-war and environmental activists. Similarly, the anti-war movement's focus on systemic critique resonated with environmentalists addressing corporate and governmental accountability. The 20th century's protests were not confined to specific regions; they were part of a global wave of activism that challenged established power structures and advocated for justice, equality, and sustainability.

Technological advancements, such as television and later the internet, played a crucial role in amplifying these movements. Media coverage of events like the Selma to Montgomery marches or the Kent State shootings brought the struggles and injustices to a global audience, fostering solidarity and support. The legacy of these movements continues to shape contemporary activism, with modern protests for racial justice, climate action, and peace drawing on the strategies and ideals of their 20th-century predecessors. Through their resilience and innovation, these movements redefined the possibilities of political protest and left an indelible mark on history.

Are Political Parties Still Relevant in Today's Globalized Society?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political protest has roots in ancient civilizations, with one of the earliest recorded instances being the Kesh Temple Hymn in Sumer (modern-day Iraq) around 2500 BCE, which criticized social inequality and injustice.

In 404 BCE, Athenian women staged a protest against the oligarchical rule of the Thirty Tyrants, demanding the restoration of democracy and the rights of citizens.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw the rise of large-scale political protests, such as the French Revolution (1789) and the Chartist movement in Britain (1838–1848), which demanded political reforms and workers' rights.

The Boston Tea Party in 1773 is often considered one of the first major political protests in the United States, where colonists protested British taxation policies by dumping tea into Boston Harbor.

The 20th century saw significant global protest movements, such as the Russian Revolution (1917), the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. (1950s–1960s), and the anti-Vietnam War protests (1960s–1970s), which shaped modern political activism.