Political printmaking has its roots in the early modern period, emerging as a powerful medium for social and political commentary during the 15th and 16th centuries. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century revolutionized the dissemination of ideas, enabling artists and activists to produce and distribute prints on a scale previously unimaginable. Early examples of political printmaking can be traced to the Protestant Reformation, where artists like Lucas Cranach the Elder used woodcuts and engravings to propagate religious and political messages. By the 17th and 18th centuries, printmaking became a vital tool during revolutions and uprisings, such as the English Civil War and the French Revolution, allowing for the rapid spread of satirical, critical, and revolutionary imagery. This marked the beginning of printmaking as a distinctively political art form, shaping public opinion and challenging authority across Europe and beyond.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Earliest Evidence | Political printmaking has roots in ancient civilizations, with examples like Chinese woodblock prints from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) depicting social and political themes. |

| European Emergence | 15th century, with the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (around 1440). This enabled wider dissemination of political messages through printed materials. |

| Key Historical Periods | - Protestant Reformation (16th century): Prints played a crucial role in spreading religious and political ideas. - French Revolution (18th century): Saw a surge in political caricatures and satirical prints. - 19th & 20th Centuries: Continued growth with movements like Socialism, Anarchism, and anti-war activism utilizing printmaking for propaganda and social commentary. |

| Techniques | Woodcut, engraving, etching, lithography, and later screen printing. |

| Purpose | - Propaganda and persuasion - Social commentary and critique - Mobilizing public opinion - Documenting historical events |

| Impact | Powerful tool for political expression, shaping public discourse, and influencing social change. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins in ancient civilizations: Early political carvings and prints on clay tablets, papyrus, and stone

- Renaissance and woodcuts: Spread of political satire and propaganda through woodblock printing in Europe

- French Revolution impact: Rise of affordable, mass-produced prints to mobilize public opinion and dissent

- th-century lithography: Advancement in printing technology enabling wider distribution of political messages

- Modern movements (20th century): Role of printmaking in activism, from suffrage to anti-war protests

Origins in ancient civilizations: Early political carvings and prints on clay tablets, papyrus, and stone

The origins of political printmaking can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where early forms of visual communication served political and social purposes. Long before the invention of the printing press, societies used available materials like clay, papyrus, and stone to create carvings and prints that conveyed political messages, documented laws, and celebrated rulers. These early works laid the foundation for what would later evolve into more sophisticated forms of political printmaking.

In ancient Mesopotamia, clay tablets were a primary medium for recording political and administrative information. The Sumerians, Akkadians, and Babylonians inscribed cuneiform script onto wet clay, which was then dried or fired to create durable records. Among these tablets were decrees from kings, legal codes like Hammurabi's Code, and accounts of military victories. These inscriptions served both as historical documentation and as tools to legitimize the authority of rulers. While not "prints" in the modern sense, these clay tablets were among the earliest forms of political communication that involved reproduction and dissemination of text and imagery.

Ancient Egypt utilized papyrus and stone for political and religious carvings and inscriptions. Hieroglyphs on temple walls, tombs, and monuments often depicted pharaohs, gods, and significant events, reinforcing the divine authority of rulers. The Rosetta Stone, for example, is a political decree issued by Egyptian priests in 196 BCE, commemorating the rule of Ptolemy V. Such carvings and inscriptions were not mass-produced but were strategically placed to communicate power and ideology to both the elite and the public. Similarly, papyrus scrolls were used to document laws, treaties, and administrative records, though their production was limited due to the labor-intensive nature of the material.

In ancient China, political messages were carved onto stone steles and bronze vessels. The Stone Classics of the Qin Dynasty, for instance, were inscriptions of Confucian texts commissioned by Emperor Qin Shi Huang to standardize thought and governance. These carvings served as both educational tools and assertions of imperial authority. Additionally, seals and stamps made from stone or metal were used to imprint official documents, marking the earliest forms of political "printing" in the sense of reproducing a standardized symbol of authority.

The Indus Valley Civilization also produced political and administrative seals, often made from steatite, featuring inscriptions and images of animals or deities. While the script remains undeciphered, these seals likely served as marks of authority or ownership, possibly used in trade or governance. These early examples demonstrate that even in ancient times, societies recognized the power of visual and textual reproduction to communicate political ideas and consolidate power.

In summary, the origins of political printmaking are deeply rooted in ancient civilizations' use of clay, papyrus, and stone for carvings and inscriptions. These early forms of visual communication served political purposes, from documenting laws and celebrating rulers to asserting authority and standardizing ideology. While not prints in the modern sense, these ancient practices highlight humanity's longstanding desire to reproduce and disseminate political messages, setting the stage for the development of more advanced printmaking techniques in later centuries.

Greek Theatre's Political Power: Shaping Democracy Through Performance

You may want to see also

Renaissance and woodcuts: Spread of political satire and propaganda through woodblock printing in Europe

The origins of political printmaking can be traced back to the Renaissance period in Europe, particularly with the advent of woodblock printing. This era, marked by a resurgence of art, culture, and intellectualism, also witnessed the emergence of woodcuts as a powerful medium for disseminating political satire and propaganda. Woodblock printing, which originated in China and later spread to Europe, allowed for the mass production of images and texts, making it an ideal tool for conveying political messages to a wider audience. As the technology improved, artists and printers began to exploit the potential of woodcuts to create thought-provoking and often controversial works that commented on the social, religious, and political issues of the day.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, woodcut prints became increasingly popular in Europe, particularly in Germany, Italy, and the Low Countries. Artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder used woodcuts to create intricate and detailed images that often contained hidden political meanings. These prints were widely circulated, allowing people from various social classes to engage with political ideas and debates. The accessibility and affordability of woodcuts made them an effective medium for spreading political satire, as they could be easily reproduced and distributed in large quantities. This, in turn, enabled artists and printers to influence public opinion and shape political discourse.

One of the key factors that contributed to the spread of political satire through woodcuts was the rise of humanism and the Reformation. As scholars and thinkers began to challenge traditional authority and question established norms, artists responded by creating prints that critiqued the Church, monarchy, and other institutions. Woodcuts depicting satirical scenes, caricatures, and allegories became a popular means of expressing dissent and promoting reform. For instance, the works of German artist Hans Holbein the Younger often contained subtle political commentary, using symbolism and metaphor to convey complex ideas. Similarly, the French artist Barthélemy de Chasseneuz used woodcuts to illustrate his legal and political treatises, making them more accessible to a broader audience.

The use of woodcuts for political propaganda also became prevalent during this period, particularly in the context of religious conflicts and power struggles. Rulers and political factions commissioned artists to create prints that promoted their agendas and disparaged their opponents. These prints often depicted idealized versions of historical events, heroic leaders, or demonic enemies, using emotional and symbolic language to sway public opinion. The Protestant Reformation, in particular, saw an explosion of political printmaking, as reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin used woodcuts to disseminate their ideas and criticize the Catholic Church. The famous "Passional Christi und Antichristi" (The Passion of Christ and Antichrist), a series of woodcuts by Lucas Cranach the Elder, is a notable example of how artists used visual propaganda to promote religious and political reform.

As the Renaissance gave way to the Baroque period, the tradition of political printmaking continued to evolve, with artists experimenting with new techniques and styles. However, the foundations laid during the Renaissance – particularly the use of woodcuts for political satire and propaganda – remained a significant influence. The accessibility, affordability, and versatility of woodblock printing had democratized the dissemination of political ideas, enabling artists to play a crucial role in shaping public opinion and challenging authority. By examining the role of woodcuts in the spread of political satire and propaganda during the Renaissance, we can gain a deeper understanding of the historical roots of political printmaking and its enduring impact on art, politics, and society. The legacy of Renaissance woodcuts can still be seen today, as artists continue to use printmaking and other mediums to engage with political issues and provoke critical thought.

Political Polarization's Impact: Dividing Societies, Weakening Democracies, and Fueling Conflict

You may want to see also

French Revolution impact: Rise of affordable, mass-produced prints to mobilize public opinion and dissent

The French Revolution (1789–1799) marked a pivotal moment in the history of political printmaking, as it catalyzed the rise of affordable, mass-produced prints that became powerful tools for mobilizing public opinion and dissent. Prior to the Revolution, printmaking was largely confined to elite circles, with engravings and etchings serving religious, artistic, or monarchical purposes. However, the tumultuous social and political upheaval of the late 18th century transformed printmaking into a weapon of ideological warfare. Advances in printing technology, such as the widespread adoption of woodcut, copperplate, and later lithography, enabled the rapid and inexpensive production of images and texts. This democratization of print culture allowed revolutionary ideas to spread far beyond Paris, reaching rural areas and urban centers alike.

The affordability and accessibility of prints during the French Revolution were instrumental in shaping public discourse. Pamphlets, caricatures, and broadsheets became ubiquitous, often depicting key figures like Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and revolutionary leaders such as Robespierre and Marat. These prints were not merely informative but also highly persuasive, using symbolism, satire, and emotive imagery to sway public sentiment. For instance, the iconic image of Marianne, the personification of the French Republic, was disseminated widely to inspire patriotism and unity. Similarly, caricatures of the monarchy, such as James Gillray’s biting satires, exposed their excesses and fueled anti-royalist sentiment. The ability to produce these prints in large quantities ensured that revolutionary ideals and grievances were amplified, fostering a sense of collective identity among the populace.

The role of printmakers and publishers during this period cannot be overstated. Artists and printers aligned themselves with various factions, producing works that either supported or criticized the Revolution. Figures like Jacques-Louis David, though primarily a painter, influenced print culture through his neoclassical style, which glorified revolutionary virtues. Meanwhile, anonymous printmakers created more radical and subversive works, often distributed clandestinely to avoid censorship. The National Assembly itself recognized the power of print, commissioning works to legitimize its authority and disseminate decrees. This symbiotic relationship between political actors and printmakers underscores the medium’s centrality in shaping the Revolution’s trajectory.

The impact of mass-produced prints extended beyond France, influencing political movements across Europe and beyond. The ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity, disseminated through prints, inspired similar uprisings and reforms in other nations. The French Revolution thus served as a model for how visual media could be harnessed to challenge established power structures and mobilize the masses. This legacy laid the groundwork for the use of political printmaking in subsequent revolutions, from the 1848 uprisings to the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Revolution’s reliance on print culture marked a turning point, demonstrating the potential of affordable, widely distributed imagery to drive social and political change.

In conclusion, the French Revolution was a watershed moment in the history of political printmaking, as it popularized the use of affordable, mass-produced prints to mobilize public opinion and dissent. By leveraging advances in printing technology and the power of visual communication, revolutionaries transformed print culture into a dynamic force for change. The widespread dissemination of prints not only shaped the course of the Revolution but also established a template for future political movements to utilize visual media as a tool of resistance and propaganda. The Revolution’s impact on printmaking thus remains a testament to the enduring power of art to influence history.

Why Don’t You Practice Politeness? Exploring the Decline of Courtesy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

19th-century lithography: Advancement in printing technology enabling wider distribution of political messages

The 19th century marked a pivotal era in the history of political printmaking, largely due to the advancements in lithography, a printing technique that revolutionized the dissemination of political messages. Lithography, invented by Alois Senefelder in 1796, gained widespread adoption in the early 1800s. Unlike traditional woodcut or engraving methods, lithography allowed for more detailed and nuanced images to be produced with greater ease and at a lower cost. This technological leap enabled artists and political activists to create and distribute prints more efficiently, making it a powerful tool for political expression and propaganda.

One of the key advantages of lithography was its ability to reproduce images in large quantities without significant loss of quality. This was particularly important during a time of rising literacy rates and growing public engagement with political issues. Political cartoons, caricatures, and satirical prints became increasingly popular as they could be mass-produced and sold at affordable prices. Artists like Honoré Daumier in France and Thomas Nast in the United States used lithography to critique social injustices, corrupt politicians, and pressing issues of the day, such as slavery, industrialization, and class inequality. Their works not only entertained but also educated and mobilized public opinion.

The portability and affordability of lithographic prints made them accessible to a broader audience, including the working class. This democratization of political imagery played a crucial role in shaping public discourse during pivotal moments of the 19th century, such as the revolutions of 1848 in Europe and the American Civil War. For instance, abolitionist movements in both Europe and the United States utilized lithography to produce powerful visuals that highlighted the horrors of slavery, thereby galvanizing support for their cause. Similarly, labor movements and socialist organizations employed lithographic prints to advocate for workers' rights and social reform.

Lithography also facilitated the spread of political messages across borders, fostering international solidarity and awareness. Prints could be easily transported and translated, allowing ideas to transcend linguistic and cultural barriers. This was evident in the circulation of revolutionary imagery during the 1848 uprisings, where lithographs depicting scenes of resistance and liberation inspired similar movements in other countries. The medium's versatility and speed of production ensured that political events could be documented and disseminated almost in real-time, a significant advancement over earlier printing methods.

In conclusion, 19th-century lithography was a transformative force in the realm of political printmaking. Its technical innovations enabled the wider distribution of political messages, empowering artists and activists to reach unprecedented audiences. By making political imagery more accessible and affordable, lithography played a critical role in shaping public opinion, mobilizing social movements, and documenting the tumultuous events of the era. This period laid the foundation for the continued use of print media as a tool for political expression and advocacy in the centuries that followed.

How Political Parties Streamline Governance and Reduce Transaction Costs

You may want to see also

Modern movements (20th century): Role of printmaking in activism, from suffrage to anti-war protests

The 20th century witnessed a profound intersection between printmaking and political activism, as artists harnessed the medium's accessibility and reproducibility to amplify their messages. One of the earliest and most significant movements where printmaking played a pivotal role was the women's suffrage campaign. In the early 1900s, suffragists in the United States and the United Kingdom utilized posters, pamphlets, and postcards to advocate for women's right to vote. Artists like the British suffragette Mary Lowndes created bold, visually striking prints that were distributed widely, often featuring symbols such as the color purple, white, and green, which represented dignity, purity, and hope. These prints were not only artistic expressions but also powerful tools for mobilization, educating the public and rallying supporters to the cause.

During the mid-20th century, printmaking became a vital medium for anti-war protests, particularly in response to World War I and later the Vietnam War. Artists used techniques like woodcut, lithography, and screen printing to produce works that critiqued militarism and its consequences. For instance, the German artist Käthe Kollwitz created hauntingly powerful prints during World War I, depicting the suffering of civilians and the futility of war. Her work, such as the series *War* (1922), resonated deeply with anti-war sentiments and remains a testament to the emotional and political impact of printmaking. Similarly, during the Vietnam War, artists like American printmaker Faith Ringgold used their work to protest the conflict, often incorporating text and imagery that directly addressed the human cost of war.

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States also saw printmaking emerge as a critical tool for activism. Artists and organizers produced posters, flyers, and broadsides that highlighted issues of racial inequality and called for justice. The Black Arts Movement, in particular, embraced printmaking as a means of cultural and political expression. Artists like Emory Douglas, the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, created iconic posters and illustrations that combined bold graphics with revolutionary messages. These prints were distributed widely, often in newspapers and community spaces, serving as both art and propaganda to inspire and unite activists.

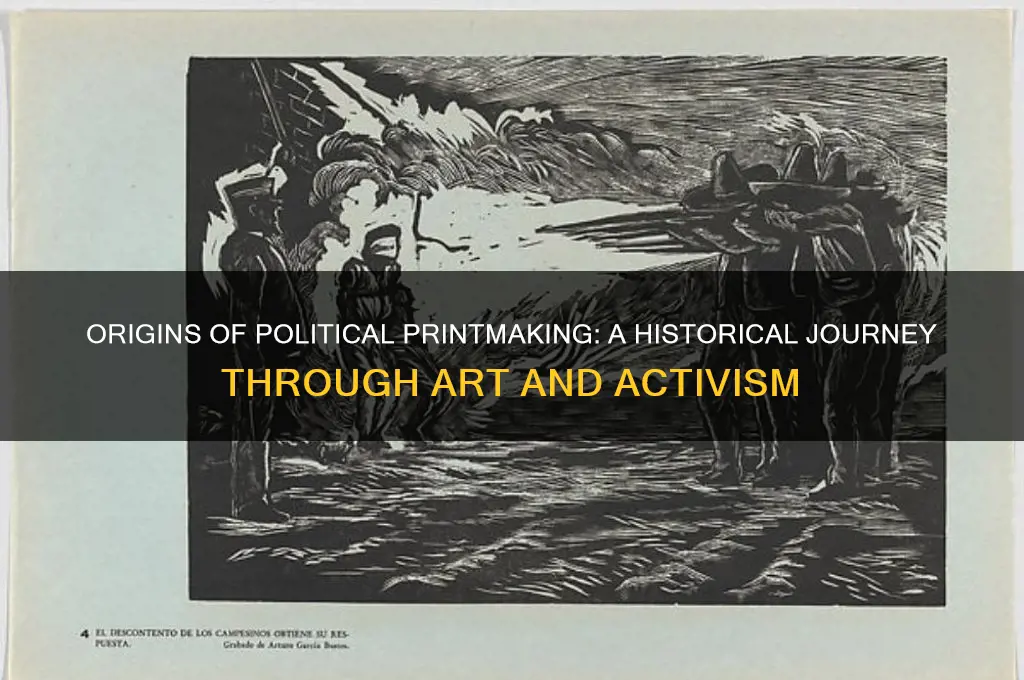

In Latin America, printmaking became a cornerstone of political resistance during the 20th century, especially in countries experiencing dictatorships and social unrest. The Mexican Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop), founded in 1937, was a collective of artists dedicated to creating prints that addressed social and political issues. Their works often depicted labor rights, indigenous struggles, and anti-imperialist themes, using accessible and affordable techniques like linoleum cuts and woodcuts. Similarly, in Chile under Augusto Pinochet’s regime, artists like Roberto Matta and others used printmaking to denounce human rights abuses and political oppression, often distributing their works clandestinely to evade censorship.

Throughout the 20th century, printmaking's role in activism was defined by its ability to reach broad audiences and convey powerful messages in a visually compelling way. Its affordability and ease of reproduction made it an ideal medium for movements that relied on grassroots mobilization. From suffrage to anti-war protests, civil rights, and anti-dictatorship struggles, printmaking served as both a mirror and a megaphone, reflecting the injustices of the time while amplifying the voices of those fighting for change. This legacy continues to inspire contemporary artists and activists who use printmaking to address the pressing issues of today.

Hitler's Rise: How He Eliminated All Political Parties in Germany

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political printmaking has its roots in the 15th century, with early examples emerging during the Renaissance. However, it gained significant traction in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly during periods of social and political upheaval such as the Protestant Reformation and the Thirty Years' War.

The earliest forms of political printmaking were used to disseminate propaganda, critique authority, and mobilize public opinion. Woodcuts and engravings were popular mediums, often depicting satirical or allegorical scenes to convey political messages to both literate and illiterate audiences.

The French Revolution (1789–1799) is often cited as a turning point for political printmaking. The period saw an explosion of prints, posters, and caricatures that supported or opposed revolutionary ideals, making printmaking a powerful tool for political expression and activism.