Political comics, as a distinct form of satirical expression, trace their origins back to the 18th century, with early examples appearing in European publications during the Enlightenment. One of the earliest notable works is William Hogarth’s *A Rake’s Progress* (1735), a series of engravings that critiqued societal vices and moral decay. However, the more recognizable form of political cartoons emerged in the 19th century, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars, when artists like James Gillray in Britain used caricatures to lampoon political figures and events. In the United States, political cartoons gained prominence during the 1800s, with publications like *Harper’s Weekly* featuring artists such as Thomas Nast, who famously targeted political corruption and the Tammany Hall machine. These early works laid the foundation for political comics as a powerful tool for social and political commentary, blending humor, art, and critique to engage audiences and challenge authority.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Earliest Known Examples | 16th Century (e.g., Thomas Rowlandson's caricatures in Britain, William Hogarth's satirical prints) |

| Formalization of Political Cartoons | 18th Century (during the Enlightenment and the American and French Revolutions) |

| Key Publications | The London Magazine (1732), Punch (1841), Harper's Weekly (1857) |

| Pioneering Cartoonists | James Gillray, Thomas Nast, Honoré Daumier |

| Technological Influence | Printing press enabled mass production and distribution |

| Major Themes | Political corruption, social inequality, war, and power struggles |

| Cultural Impact | Shaped public opinion, influenced political discourse, and documented historical events |

| Global Spread | 19th Century (spread to Europe, the Americas, and beyond) |

| Modern Era | 20th Century (digital media expanded reach and formats, e.g., webcomics, social media) |

| Notable Modern Examples | Doonesbury, Calvin and Hobbes, The Onion, xkcd |

Explore related products

$112.95 $31.95

What You'll Learn

Early Political Cartoons in 18th Century

The origins of political cartoons can be traced back to the 18th century, a period marked by significant social, political, and cultural transformations. This era, often referred to as the Age of Enlightenment, saw the rise of new ideas about governance, individual rights, and the role of the press. It was within this intellectual and political ferment that early political cartoons began to emerge as a powerful tool for commentary and critique. The 18th century laid the groundwork for what would become a staple of political discourse, combining art with satire to influence public opinion.

One of the earliest and most influential figures in the development of political cartoons was William Hogarth, an English artist active in the first half of the 18th century. Although Hogarth is best known for his moralizing series of paintings and engravings, his works often contained political undertones. For instance, his series *A Rake’s Progress* (1735) critiqued the excesses of the upper class, while *Gin Lane* (1751) highlighted the social issues caused by widespread gin consumption, indirectly criticizing government policies. Hogarth’s visual narratives set a precedent for using art to comment on societal and political issues.

The latter half of the 18th century saw the rise of James Gillray, often regarded as the father of the modern political cartoon. Gillray’s caricatures, published in the 1780s and 1790s, were sharply satirical and targeted prominent political figures of the time, including King George III and Napoleon Bonaparte. His work *The Plumb-pudding in Danger* (1805) is a classic example, depicting Britain and France carving up the world like a pudding, satirizing their imperial ambitions. Gillray’s cartoons were widely circulated and played a significant role in shaping public opinion during a tumultuous period of European history.

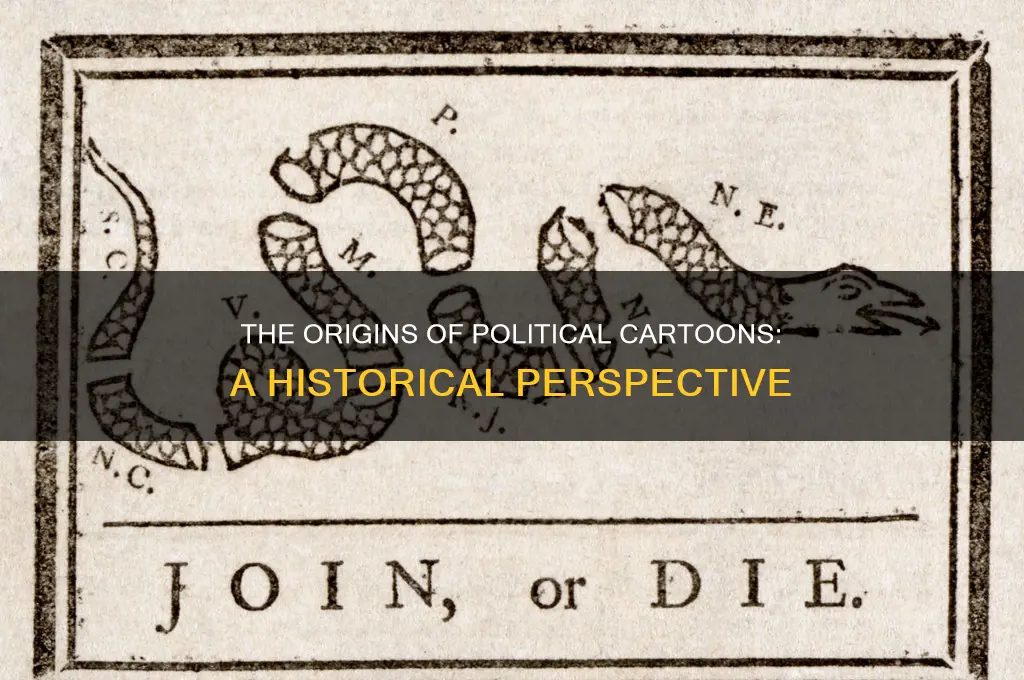

Political cartoons also flourished in the American colonies during the 18th century, particularly in the lead-up to and during the American Revolution. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers, created one of the earliest American political cartoons, *Join, or Die* (1754), which depicted a snake cut into segments, each labeled with the name of a colony, to advocate for unity against the French and their Native American allies. This image became a powerful symbol of colonial solidarity and was later repurposed during the Revolutionary War. Similarly, cartoons criticizing British policies, such as the Stamp Act and the Tea Act, were widely distributed in newspapers and pamphlets, helping to galvanize public support for independence.

The 18th century’s political cartoons were not limited to Europe and America; they also appeared in other parts of the world, though less prominently. In France, for example, satirical prints known as *charges* gained popularity during the reign of Louis XVI and played a role in the build-up to the French Revolution. These prints often mocked the monarchy and the aristocracy, contributing to the growing discontent among the populace. Across the globe, the medium of visual satire proved to be a versatile and effective means of political expression.

In conclusion, the 18th century marked the beginning of political cartoons as a distinct and influential form of communication. Artists like Hogarth and Gillray in Britain, and figures like Benjamin Franklin in America, pioneered the use of visual satire to critique power, shape public opinion, and mobilize political movements. Their work not only reflected the issues of their time but also established a tradition that continues to thrive in modern political discourse. The early political cartoons of the 18th century were more than just humorous drawings; they were powerful tools of resistance, education, and social change.

When Are Political Polls Conducted and Why Timing Matters

You may want to see also

Role of Newspapers in Popularizing Comics

The role of newspapers in popularizing comics, particularly political cartoons, is a pivotal chapter in the history of visual satire. Political comics, as we understand them today, began to take shape in the 18th century, with early examples appearing in European publications. However, it was the advent of mass-circulation newspapers in the 19th century that truly democratized access to these artworks, embedding them into the daily lives of readers. Newspapers provided a platform for artists to comment on political and social issues, reaching a broad audience that spanned various socioeconomic classes. This accessibility was crucial in elevating political comics from niche, elite publications to a widely recognized medium for public discourse.

Newspapers not only disseminated political comics but also played a key role in shaping their style and content. Editors often commissioned cartoons that aligned with their publication’s political stance, fostering a symbiotic relationship between artists and newspapers. For instance, iconic cartoonists like Thomas Nast in the United States used platforms like *Harper's Weekly* to critique corruption and influence public opinion during the Gilded Age. Nast’s cartoons, such as those targeting Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall machine, demonstrated the power of visual satire in holding those in power accountable. This editorial support allowed political comics to become a staple of journalistic commentary, blending entertainment with incisive critique.

The serialization of comics in newspapers further contributed to their popularity. Daily or weekly strips became a highly anticipated feature, encouraging reader loyalty and engagement. Political cartoons, in particular, thrived in this format, as they could respond swiftly to current events. Newspapers like *Punch* in the UK and *Le Charivari* in France set the standard for satirical publications, inspiring similar ventures globally. The ability to publish timely, relevant content ensured that political comics remained a dynamic and influential medium, capable of shaping public perception on pressing issues.

Technological advancements in printing also played a significant role in the newspaper-comics relationship. The introduction of lithography and later, photomechanical reproduction, allowed for more detailed and visually appealing cartoons. This not only enhanced the artistic quality of political comics but also made them more accessible to a wider audience. Newspapers could now print cartoons in larger quantities and at a lower cost, further cementing their place in popular culture. The visual impact of these cartoons often transcended language barriers, making them a universal tool for political expression.

Finally, newspapers acted as a launching pad for many cartoonists who would go on to become household names. By providing a steady income and exposure, newspapers enabled artists to refine their craft and develop distinctive styles. This, in turn, elevated the status of political comics from mere illustrations to a respected form of journalism. The legacy of this partnership is evident in the continued presence of editorial cartoons in modern newspapers and digital media, proving that the role of newspapers in popularizing comics was not just historical but foundational to the medium’s enduring relevance.

Why Young Americans Are Turning Away from Politics

You may want to see also

Influence of the American Revolution on Satire

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a pivotal moment in history that not only reshaped political landscapes but also profoundly influenced the development of satire, including political comics. As tensions between the American colonies and Britain escalated, satire emerged as a powerful tool for expressing dissent, critiquing authority, and mobilizing public opinion. Political cartoons, in particular, became a popular medium for conveying complex ideas in a visually accessible and impactful way. The Revolution marked one of the earliest instances where satire was systematically used to challenge established power structures, laying the groundwork for the modern political comic.

One of the most significant figures in this context was Benjamin Franklin, whose satirical writings and cartoons predated the Revolution but set the stage for its use as a political weapon. Franklin’s famous "Join, or Die" cartoon (1754), depicting a fragmented snake representing the colonies, was repurposed during the Revolution to advocate for unity against British rule. This visual metaphor exemplifies how satire could simplify political arguments and rally support. The success of such imagery during the Revolution demonstrated the potential of comics to influence public sentiment, making them an essential tool in the fight for independence.

British cartoonists also played a role in shaping satirical discourse during this period. Artists like James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, though based in Britain, created works that commented on the American Revolution, often mocking both British leadership and the colonial rebels. These cartoons, circulated across the Atlantic, highlighted the global reach of satire and its ability to transcend borders. The Revolution thus fostered a transatlantic dialogue through satire, where political comics became a means of both resistance and ridicule, depending on the perspective.

The American Revolution’s impact on satire extended beyond its immediate context, influencing the emergence of political comics as a distinct genre. The use of caricatures, symbolism, and humor to critique authority became a hallmark of political satire worldwide. For instance, the Revolutionary-era practice of depicting King George III as a tyrant set a precedent for portraying leaders in unflattering ways. This tradition continued in the decades following the Revolution, inspiring future generations of cartoonists to use their craft to hold power to account.

In conclusion, the American Revolution was a catalyst for the evolution of political satire, particularly in the form of comics. It demonstrated the power of visual humor to shape public opinion, challenge authority, and mobilize movements. The techniques and themes developed during this period—such as the use of symbolism, caricature, and biting humor—became foundational elements of political comics. Thus, the Revolution not only marked the beginning of a new nation but also the rise of satire as a critical and enduring force in political discourse.

Understanding the Structure and Organization of Political Parties Worldwide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Development of British Political Caricatures

The origins of political caricatures in Britain can be traced back to the 18th century, a period marked by significant social, political, and cultural changes. The emergence of a vibrant print culture, coupled with the rise of a more engaged and literate public, created a fertile ground for the development of satirical artwork. One of the earliest and most influential figures in this realm was William Hogarth, often regarded as the father of British political satire. Hogarth's works, such as his series of engravings titled "A Rake's Progress" (1735) and "Marriage à-la-mode" (1745), used visual storytelling to critique societal morals and political corruption, setting a precedent for the use of art as a tool for social commentary.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the proliferation of political caricatures, driven by the tumultuous political landscape of the time, including the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Napoleonic Wars. Artists like James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson became prominent figures, their works widely circulated in print shops and coffeehouses. Gillray, in particular, is celebrated for his sharp wit and biting satire, often targeting prominent political figures such as King George III and Napoleon Bonaparte. His caricature "The Plumb-pudding in danger" (1805) is a quintessential example of his ability to capture the complexities of international politics in a single, humorous image.

The development of British political caricatures was also closely tied to advancements in printing technology. The introduction of wood engraving and later, lithography, made it possible to produce and distribute satirical prints more efficiently and affordably. This democratization of political satire allowed a broader audience to engage with these works, fostering a culture of political discourse and critique. Newspapers and periodicals began to incorporate caricatures, further embedding them into the public consciousness. Publications like *Punch*, founded in 1841, played a pivotal role in popularizing political cartoons, with artists like John Leech and Sir John Tenniel contributing iconic works that continue to influence political satire today.

The Victorian era witnessed the maturation of British political caricatures, as artists began to explore more nuanced and symbolic approaches to their work. The rise of the Liberal and Conservative parties provided ample material for satirists, who often depicted political leaders and policies through exaggerated and humorous visuals. Artists like George Du Maurier and Harry Furniss expanded the scope of political caricature, addressing not only national politics but also social issues such as poverty, industrialization, and women's suffrage. This period also saw the emergence of female caricaturists, though they were fewer in number, contributing to a more diverse and inclusive satirical landscape.

In the 20th century, British political caricatures continued to evolve, adapting to new mediums and technologies. The advent of photography and later, television, posed challenges to traditional print-based satire, but also opened up new avenues for expression. Cartoonists like David Low and Gerald Scarfe became household names, their works appearing in major newspapers and magazines. Low's depiction of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin in "All Behind You, Winston! He's Going to Do It!" (1940) is a powerful example of how political caricatures could influence public opinion during wartime. The latter half of the century saw the rise of digital media, enabling political cartoons to reach global audiences instantaneously, ensuring their continued relevance in the modern political discourse.

Throughout its development, British political caricature has remained a dynamic and essential component of the nation's cultural and political identity. From Hogarth's moral critiques to the digital satires of today, these artworks have provided a mirror to society, reflecting its virtues, vices, and complexities. The tradition of British political caricature not only entertains but also educates, encouraging critical thinking and engagement with the issues that shape our world. Its evolution is a testament to the enduring power of visual storytelling in the realm of political commentary.

Can Political Parties Expel Members? Understanding Party Discipline and Removal

You may want to see also

Emergence of Comics During the French Revolution

The emergence of political comics can be traced back to the late 18th century, with the French Revolution serving as a pivotal moment in their development. During this tumultuous period, visual satire and caricature became powerful tools for expressing political dissent and shaping public opinion. The French Revolution, which began in 1789, created a fertile ground for the rise of political comics, as artists sought to capture the chaos, ideals, and conflicts of the era in a format accessible to a broad audience.

One of the key figures in this early wave of political comics was James Gillray, a British caricaturist whose work often commented on French revolutionary events. However, it was in France itself that the medium truly flourished as a political tool. French artists like Honoré Daumier and, earlier, artists inspired by the Revolution, began creating images that critiqued the monarchy, the clergy, and the emerging political factions. These works were not yet in the form of sequential art or comic strips as we know them today, but they laid the groundwork for visual storytelling with a political edge.

The French Revolution's emphasis on liberty, equality, and fraternity also inspired artists to use their work to educate and mobilize the masses. Broadside prints and caricatures were widely distributed in public spaces, coffeehouses, and markets, making them an effective means of communication in a largely illiterate society. These images often depicted revolutionary figures like Robespierre and Marat, as well as allegorical representations of the Revolution's ideals and its enemies. The visual nature of these works allowed them to transcend language barriers and resonate with a diverse audience.

The period also saw the emergence of serialized publications that included political cartoons, though they were not yet structured as modern comics. Journals like *Le Père Duchesne*, edited by Jacques Hébert, combined text with bold, provocative images to attack the monarchy and promote revolutionary ideals. These publications were instrumental in shaping public discourse and fostering a culture of political engagement through visual means. The combination of text and image in these early works marked a significant step toward the development of comics as a distinct medium.

By the end of the French Revolution, the use of visual satire and caricature had become an established part of political communication. While the term "comic" in its modern sense did not yet exist, the foundations were laid for the political comic as a form of art and activism. The Revolution's legacy in this regard is undeniable, as it demonstrated the power of visual storytelling to influence political thought and action. This period thus marks a crucial chapter in the history of political comics, setting the stage for their evolution in the centuries to come.

Does MADD's Advocacy Favor One Political Party Over Another?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political comics date back to ancient civilizations, with examples found in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Roman graffiti, but they gained prominence in the 18th century during the Enlightenment.

British artist William Hogarth is often credited as a pioneer, but Thomas Nast, an American cartoonist in the 19th century, is widely regarded as the father of modern political cartoons for his influential work in publications like *Harper's Weekly*.

Political comics became a staple in newspapers during the 19th century, particularly in the 1840s and 1850s, as printing technology advanced and newspapers sought engaging ways to comment on current events.