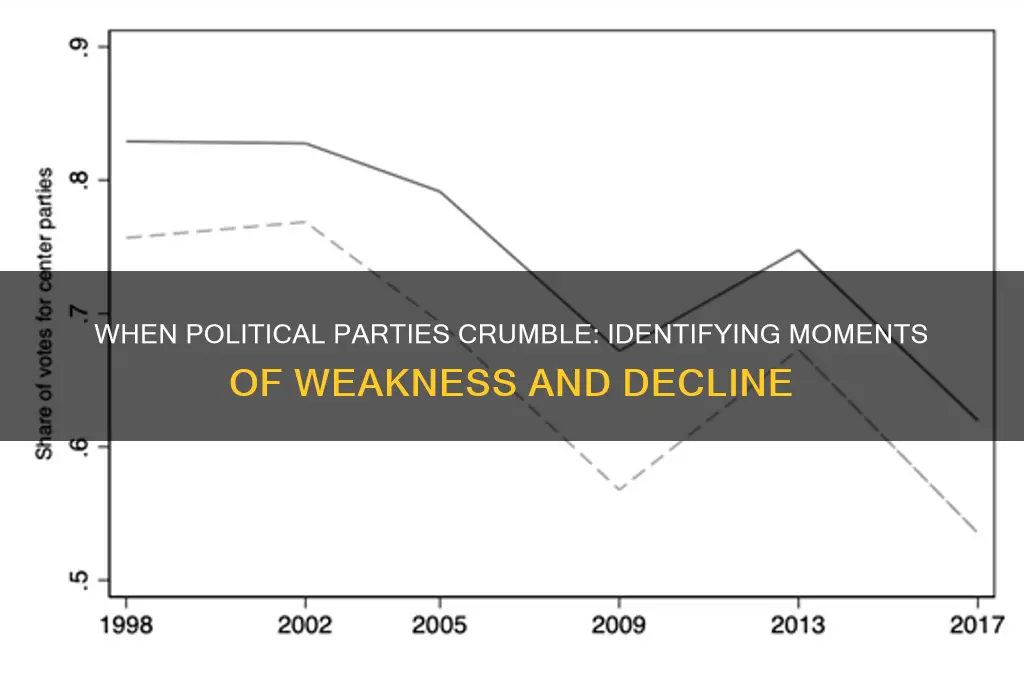

Political parties are often at their weakest during periods of significant internal division, external crises, or shifts in public sentiment. Internal conflicts, such as ideological splits or leadership disputes, can erode party unity and diminish their ability to effectively mobilize supporters or craft coherent policies. Externally, parties may weaken during economic downturns, scandals, or when they fail to address pressing societal issues, leading to a loss of public trust and electoral support. Additionally, rapid changes in the political landscape, such as the rise of populist movements or the emergence of new issues like climate change, can render traditional party platforms outdated and less appealing. These moments of vulnerability often coincide with declining membership, reduced fundraising, and poor electoral performance, forcing parties to either adapt or risk becoming marginalized in the political arena.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Low Public Approval | Approval ratings below 40% (e.g., U.S. Congress approval at 20% in 2023). |

| Internal Divisions | Frequent leadership challenges or public infighting (e.g., UK Labour Party in 2023). |

| Election Defeats | Significant losses in national or local elections (e.g., BJP in Indian state elections, 2023). |

| Loss of Core Supporters | Decline in traditional voter base (e.g., Democrats losing rural voters in the U.S.). |

| Scandals or Corruption | High-profile scandals affecting party leadership (e.g., ANC in South Africa, 2023). |

| Economic Downturn | Governing parties blamed for economic crises (e.g., inflation in the Eurozone, 2023). |

| Rise of Populism/Third Parties | Increased support for populist or independent candidates (e.g., France's National Rally, 2023). |

| Policy Failures | Major policy initiatives failing or unpopular (e.g., healthcare reforms in Germany, 2023). |

| Leadership Vacuum | Lack of strong, unifying leadership (e.g., Conservative Party in the UK post-Boris Johnson). |

| External Shocks | Global crises weakening party credibility (e.g., COVID-19 response criticism in multiple countries). |

Explore related products

$43.89 $48.59

What You'll Learn

- Post-Scandal Fallout: Public trust plummets after corruption or ethical breaches within party leadership

- Election Defeats: Consecutive losses weaken party influence, funding, and member morale significantly

- Internal Divisions: Factionalism and ideological splits fragment party unity and decision-making power

- Policy Failures: Failed policies or unfulfilled promises erode voter confidence and support

- Leadership Vacuum: Absence of strong, charismatic leaders leaves parties directionless and vulnerable

Post-Scandal Fallout: Public trust plummets after corruption or ethical breaches within party leadership

Scandals involving corruption or ethical breaches within party leadership can be devastating, eroding public trust and leaving political parties vulnerable. The aftermath of such events often reveals a party at its weakest, struggling to regain credibility and support. Consider the case of the 2017 "Cash-for-Honors" scandal in the UK, where the Conservative Party faced allegations of offering peerages in exchange for financial contributions. The fallout led to a significant decline in public trust, with polls showing a 10-point drop in approval ratings within weeks of the scandal breaking. This example illustrates how swiftly and severely public opinion can turn against a party when its leadership is implicated in unethical behavior.

To mitigate the damage, parties must act decisively and transparently. A three-step approach can be effective: first, acknowledge the breach and take responsibility; second, implement immediate corrective measures, such as leadership resignations or policy reforms; and third, engage in sustained public outreach to rebuild trust. For instance, after the 2013 "Whitewater" scandal in the United States, the Democratic Party faced intense scrutiny over financial dealings involving Bill and Hillary Clinton. While the scandal did not lead to criminal charges, the party’s slow response exacerbated public distrust. In contrast, the swift and comprehensive reforms enacted by the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan following the 2010 political funds scandal helped them recover more quickly, demonstrating that proactive measures can limit long-term damage.

Comparatively, parties that fail to address scandals effectively often face prolonged weakness. The African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa provides a cautionary tale. Despite numerous corruption allegations, including the 2016 "State Capture" scandal, the ANC’s leadership has often denied wrongdoing or delayed accountability. This approach has led to a steady decline in electoral support, with the party losing its majority in key municipalities for the first time in 2021. This example underscores the importance of not just addressing scandals but doing so in a manner that reassures the public of genuine reform.

Persuasively, it’s clear that the public’s memory of scandals is long, and parties cannot afford to underestimate the impact of ethical breaches. A practical tip for party leadership is to establish independent ethics committees before scandals arise, ensuring swift and impartial investigations when issues emerge. Additionally, parties should invest in regular training for members on ethical standards and transparency practices. These proactive steps can reduce the likelihood of scandals and position a party to respond more effectively if one occurs.

In conclusion, post-scandal fallout is a critical period that tests a party’s resilience and commitment to integrity. By learning from past examples, implementing structured responses, and prioritizing transparency, parties can minimize the erosion of public trust and work toward recovery. The weakest moments for political parties often arise from their handling of scandals, but they also present opportunities to demonstrate accountability and rebuild stronger foundations for the future.

Climbing the Political Ladder: Strategies for Rising in Your Party

You may want to see also

Election Defeats: Consecutive losses weaken party influence, funding, and member morale significantly

Consecutive election defeats act as a political stress test, exposing vulnerabilities and accelerating decline within a party's infrastructure. Each loss chips away at the foundation of influence, eroding public trust and diminishing the party's ability to shape policy narratives. The Democratic Party in the United States during the 1920s, for instance, suffered a series of defeats that relegated them to a minority status, allowing the Republican Party to dominate both legislative and executive branches. This period illustrates how repeated failures at the polls can marginalize a party's voice in critical national debates.

Funding, the lifeblood of political operations, dries up rapidly in the wake of consecutive losses. Donors, both individual and corporate, are results-driven and tend to redirect resources toward parties or candidates with higher winning probabilities. The UK's Liberal Democrats experienced this stark reality after their coalition with the Conservatives in 2010 led to a series of electoral setbacks. By 2015, their parliamentary representation plummeted from 57 to 8 seats, and their funding base shrank dramatically as donors shifted allegiance to more viable parties. This financial hemorrhage cripples campaign capabilities, limiting outreach, advertising, and grassroots mobilization efforts.

Member morale, often overlooked, is a critical yet fragile component of a party's resilience. Consecutive defeats foster a culture of pessimism and disillusionment among volunteers, activists, and even elected officials. The Australian Labor Party's experience in the late 1990s and early 2000s exemplifies this dynamic. After losing multiple federal elections, internal factions began to blame each other, leading to leadership spills and policy incoherence. Such infighting not only weakens the party's external appeal but also discourages new talent from joining, creating a cycle of decline that is difficult to reverse.

To mitigate the impact of consecutive losses, parties must adopt a multi-pronged strategy. First, conduct a thorough post-election analysis to identify structural weaknesses and policy misalignments with voter priorities. Second, diversify funding sources by cultivating small-dollar donors and exploring innovative fundraising platforms. Third, invest in leadership development programs to groom a new generation of candidates who can reconnect with disaffected voters. Finally, prioritize internal unity through transparent decision-making processes and inclusive policy formulation. While these steps cannot guarantee immediate success, they provide a roadmap for rebuilding strength and relevance in the aftermath of electoral setbacks.

Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists: Were They America's First Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Internal Divisions: Factionalism and ideological splits fragment party unity and decision-making power

Political parties, much like living organisms, thrive on unity and cohesion. Yet, internal divisions—driven by factionalism and ideological splits—can cripple their strength, rendering them ineffective in both governance and opposition. Consider the Labour Party in the UK during the 1980s, when the rift between the centrists and the hard-left faction led by figures like Tony Benn paralyzed decision-making and alienated voters. This example illustrates how internal strife can erode a party’s ability to function as a cohesive unit, leaving it vulnerable to external challenges.

Factionalism often arises when competing groups within a party prioritize their narrow interests over the collective good. These factions may disagree on policy priorities, leadership styles, or even the party’s core identity. For instance, the Republican Party in the U.S. has grappled with divisions between moderate conservatives and the far-right, exemplified by the Tea Party and later the Trumpist wing. Such splits dilute the party’s message, making it difficult to rally supporters or present a unified front during elections. The result? A weakened party that struggles to articulate a clear vision or mobilize its base effectively.

Ideological splits compound these challenges by creating irreconcilable differences over fundamental values. Take the Democratic Party in the U.S., where progressives and moderates frequently clash over issues like healthcare reform, climate policy, and economic inequality. These divisions not only hinder legislative progress but also create opportunities for opponents to exploit the party’s disarray. When a party’s ideological core is fractured, its ability to make decisive choices—whether in crafting policy or selecting leaders—is severely compromised.

To mitigate the impact of internal divisions, parties must adopt proactive strategies. First, fostering open dialogue between factions can help bridge gaps and identify common ground. Second, establishing clear mechanisms for resolving disputes—such as democratic voting processes or mediation—can prevent conflicts from escalating. Finally, leaders must prioritize inclusivity, ensuring that all factions feel represented and valued within the party structure. Without such measures, internal divisions will continue to sap a party’s strength, leaving it ill-equipped to navigate the complexities of modern politics.

Rob Rosenstein's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Policy Failures: Failed policies or unfulfilled promises erode voter confidence and support

Failed policies and unfulfilled promises act as political kryptonite, draining parties of their most vital resource: voter trust. This erosion occurs incrementally, each broken pledge or botched implementation chipping away at the credibility painstakingly built during campaigns. Consider the 2010 UK coalition government’s pledge to abolish tuition fees, a promise that not only went unfulfilled but was followed by a near-tripling of fees to £9,000 annually. The resulting backlash among students and their families exemplified how policy failures can alienate core demographics, transforming supporters into skeptics.

The mechanics of this trust erosion are straightforward yet devastating. Voters, particularly in an era of information saturation, possess near-instantaneous access to fact-checks and historical records. When a party’s policy collapses—whether due to poor design, inadequate funding, or external shocks—the discrepancy between rhetoric and reality becomes glaringly apparent. For instance, the 2017 rollout of the American Healthcare Act, intended to replace the Affordable Care Act, was marred by legislative chaos and public confusion, culminating in a 38% approval rating for congressional Republicans by year-end. Such failures do not merely reflect incompetence; they signal a disconnect between a party’s priorities and the electorate’s needs.

To mitigate the fallout from policy failures, parties must adopt a three-pronged strategy. First, transparency during implementation is non-negotiable. Admitting setbacks early, as New Zealand’s Labour Party did in 2020 when acknowledging delays in their KiwiBuild housing program, can soften public censure. Second, parties should pivot toward demonstrable, short-term wins to rebuild credibility. For example, after the failure of the 2003 Iraq War rationale, Tony Blair’s government refocused on domestic initiatives like the National Minimum Wage increase, a tangible policy that resonated with voters. Lastly, parties must avoid over-promising during campaigns. The 2019 Liberal Democrats’ pledge to revoke Article 50 without a referendum, which alienated both Leave and Remain voters, illustrates the dangers of staking political capital on polarizing, unattainable goals.

Comparatively, parties that recover from policy failures share a common trait: they reframe their narrative around accountability and adaptability. Canada’s Liberal Party, after the 2019 blackface scandal involving Justin Trudeau, did not merely apologize but implemented diversity training and policy reforms, signaling a commitment to change. Conversely, parties that double down on failed strategies, like the Republican Party’s continued defense of the 2017 tax bill despite its regressive impact, risk prolonging their weakness. The takeaway is clear: policy failures need not be terminal, but they demand swift, sincere, and strategic responses to reclaim voter confidence.

Post-1824 Political Landscape: Rise of New Parties and Factions

You may want to see also

Leadership Vacuum: Absence of strong, charismatic leaders leaves parties directionless and vulnerable

A political party without a strong, charismatic leader is like a ship without a rudder, adrift in a sea of competing ideologies and public opinion. The absence of such leadership creates a vacuum that can leave a party directionless, vulnerable to internal factions, and unable to articulate a clear vision to the electorate. This phenomenon is not merely theoretical; history is replete with examples where the lack of a unifying figure has led to a party’s decline. Consider the British Labour Party in the early 1980s, when the departure of Harold Wilson and the subsequent leadership struggles left the party fractured and electorally weak, paving the way for Margaret Thatcher’s dominance.

To understand the mechanics of this weakness, imagine a party as a complex organism where the leader serves as the central nervous system, coordinating actions and responses. Without a strong leader, decision-making becomes decentralized, often leading to policy incoherence. For instance, in the absence of a charismatic figure, party members may prioritize personal agendas over collective goals, resulting in a diluted platform that fails to resonate with voters. This internal disarray is exacerbated during crises, when swift and decisive action is required. A party without a clear leader is often paralyzed, unable to respond effectively to external challenges, whether economic downturns or geopolitical shifts.

The vulnerability of a leaderless party is not just internal; it extends to its external perception. Charismatic leaders serve as the face of the party, embodying its values and aspirations. They are the bridge between the party and the public, translating complex policies into relatable narratives. Without such a figure, a party risks becoming abstract and distant, struggling to connect with voters on an emotional level. Take the case of the Republican Party in the post-Reagan era, where the absence of a unifying leader led to a fragmentation of the party’s identity, making it susceptible to populist takeovers and ideological shifts.

To mitigate the effects of a leadership vacuum, parties must adopt strategic measures. First, they should focus on cultivating a pipeline of potential leaders through mentorship and training programs. This ensures that when a leader steps down, there are capable successors ready to take the helm. Second, parties should embrace collective leadership models, where decision-making is shared among a group of trusted figures. While this approach may lack the immediacy of a single charismatic leader, it fosters unity and reduces the risk of internal power struggles. Finally, parties must invest in branding and messaging that transcends individual leaders, creating a narrative that endures regardless of who is at the top.

In conclusion, a leadership vacuum is one of the most critical vulnerabilities a political party can face. It leaves the party directionless, internally divided, and disconnected from the electorate. However, by proactively cultivating leadership talent, embracing collective decision-making, and building a strong party brand, parties can minimize the impact of such vacuums. The lesson is clear: in the absence of a strong leader, the party itself must become the leader, embodying the vision and values that sustain it through turbulent times.

Robert Heinlein's Political Party: Unraveling the Author's Ideological Affiliation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties are often at their weakest during primary elections, as internal divisions and competition among candidates can expose fractures within the party.

External factors like economic crises, scandals involving key party figures, or significant policy failures can severely weaken political parties by eroding public trust.

A lack of unified leadership can weaken a political party by creating confusion among members, diluting the party’s message, and reducing its ability to mobilize supporters effectively.

Political parties often experience their weakest moments during periods of major ideological shifts, such as after significant social movements or when they fail to adapt to changing voter demographics.