Campaign finance laws in the United States regulate the use of money in federal elections, including the sources, recipients, amounts, and frequency of contributions to political campaigns. The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), limits the amount of money individuals and organisations can give to a candidate running for federal office. However, there are certain loopholes that allow political candidates to circumvent these regulations. For example, a 1996 Supreme Court ruling enabled political parties to make unlimited independent expenditures without coordinating with a candidate, effectively bypassing the FECA's contribution limits. Additionally, super PACs, or independent expenditure-only committees, can accept unlimited contributions from corporations and spend unlimited sums to advocate for or against political candidates.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Regulation | Federal Election Commission (FEC) enforces the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) |

| Jurisdiction | US House, Senate, Presidency and Vice Presidency |

| Applicability | Only to candidates and groups participating in federal elections (congressional and presidential) |

| State laws | Each state enacts and enforces its own campaign finance laws for state and local elections |

| Donations | Candidates can spend their own personal funds without limits but must report the amount to FEC |

| Corporations and unions are prohibited from making direct contributions to federal candidates | |

| Super PACs can raise and spend unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, associations and individuals | |

| Social welfare groups are not required to disclose their donors | |

| Political parties can fund "mixed-purpose" activities with soft money |

Explore related products

$20.67 $29.99

What You'll Learn

Spending personal funds

Political candidates and campaigns are typically subject to strict regulations regarding finances, including contribution limits, disclosure requirements, and restrictions on how funds can be spent. However, there are certain circumstances in which candidates may be allowed to circumvent these regulations when spending their personal funds.

When it comes to spending personal funds, candidates are generally afforded more flexibility compared to the use of campaign donations. In the United States, for example, the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) and its regulations provide specific guidelines. According to the Act, a candidate may contribute unlimited amounts of personal funds to their campaign committees without facing any restrictions. This means that a candidate can essentially spend as much of their own money as they want on their campaign without violating any campaign finance regulations.

The ability to freely spend personal funds on one's campaign offers several advantages. Firstly, it allows candidates with personal wealth to demonstrate their commitment to the campaign and can attract additional contributions from donors who perceive the candidate's financial investment as a sign of dedication and seriousness. Additionally, spending personal funds provides candidates with greater control over their campaign message and strategy. They can utilize their financial resources to promote their platform and ideas without the need to rely solely on donations, which may come with certain expectations or conditions from contributors.

However, it is important to note that while there may be no legal limits on the amount of personal funds a candidate can spend, practical considerations may come into play. Candidates need to carefully consider the potential backlash or negative perception from the public if they spend excessive amounts of personal wealth on their campaigns. Additionally, personal funds spent on a campaign are not tax-deductible, and candidates must ensure that their spending does not run afoul of any other laws or regulations outside the scope of campaign finance laws.

Launching Political Campaign Careers: Getting Started and Strategies

You may want to see also

Super PACs

Federal campaign finance laws, such as the Tillman Act of 1907 and the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, aim to regulate the sources, recipients, amounts, and frequency of contributions to political campaigns. These laws require regular disclosures of contributions and expenditures by campaigns and committees to provide transparency and mitigate corruption. However, critics argue that these laws impinge on privacy and free expression rights, while others contend they do not sufficiently address the influence of undisclosed special interests.

Despite disclosure requirements, super PACs have found ways to obscure the true sources of their funding. For example, they can choose to file reports on a "monthly" or "quarterly" basis, allowing them to spend funds before voters know the identities of donors. Additionally, super PACs can report a non-disclosing nonprofit or shell company as the donor, making it difficult to trace the original source of the funds.

Kamala HQ: A Platform for Political Empowerment

You may want to see also

Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) is the primary federal law regulating political campaign fundraising and spending in the United States. The Act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on February 7, 1972, and has been amended several times since.

The FECA imposes restrictions on the amounts of monetary or other contributions that can be made to federal candidates and parties. It also mandates the disclosure of contributions and expenditures in campaigns for federal office, with quarterly reporting requirements for campaigns. The law prohibits corporations and unions from making direct contributions to federal candidates but allows groups to establish and fund political action committees (PACs). These PACs, or super PACs, can raise and spend unlimited sums of money from various sources, but they must file regular reports with the Federal Election Commission (FEC).

The FEC is an independent regulatory agency established in 1975 to enforce the FECA. The FEC's jurisdiction covers the financing of campaigns for the US House, Senate, Presidency, and Vice Presidency. The Commission's mission is to protect the integrity of the federal campaign finance process by providing transparency and fairly enforcing federal campaign finance laws. While the FEC administers these laws, it has no jurisdiction over laws relating to ballot access, voter fraud, intimidation, or the Electoral College.

The FECA has been amended multiple times, including in 1974 following the Watergate scandal, in 1976 after the Supreme Court struck down several provisions in Buckley v. Valeo, and in 1979 to allow parties to spend unlimited amounts of hard money on activities like increasing voter turnout. In 2002, the Act underwent major revisions with the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), which banned the use of soft money by parties and changed some limits on hard money contributions.

Working for Campaigns: What's the Role Like?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.15 $18.99

State laws

While federal campaign finance laws apply to candidates and groups participating in federal elections (congressional and presidential elections), state laws govern state and local elections. Each state enacts and enforces its own campaign finance laws.

In California, for example, the Political Reform Act requires candidates and committees to file campaign statements by specified deadlines, disclosing contributions received and expenditures made. These documents are public and may be audited by the FPPC and FTB to ensure that voters are fully informed and improper practices prohibited. California law also defines several types of committees subject to campaign rules under the Act, including recipient committees, independent expenditure committees, and major donor committees. A recipient committee receives contributions of $2,000 or more per year for political purposes. An independent expenditure committee makes independent expenditures of $1,000 or more per year on California candidates or ballot measures without consulting with the affected candidate or committee. A major donor committee contributes $10,000 or more per year to California candidates or ballot measures, and it can be comprised of a business, individual, or multi-purpose organization, including a nonprofit organization.

State PACs, unregistered local party organizations, and nonfederal campaign committees may, under certain circumstances, contribute to federal candidates. However, they must comply with specific requirements, such as ensuring that the funds come from permissible sources, and they may need to register with the FEC as a federal political committee, subject to federal laws and regulations.

It is important to note that the discussion of campaign finance regulations is complex and constantly evolving. While the provided information offers a glimpse into state-level regulations, it is not exhaustive, and each state may have its own unique nuances and updates to their campaign finance laws.

Wealthy Donors: Political Campaign Contributions Explained

You may want to see also

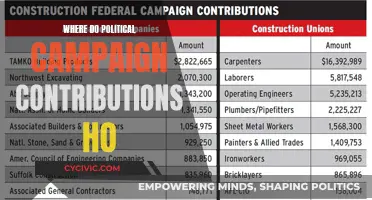

Corporate donations

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) is a key piece of legislation that sets contribution limits for individuals and organizations donating to candidates running for federal office. This act prohibits corporations and unions from making direct contributions to federal candidates. However, it allows these entities to establish and fund separate segregated funds, commonly known as political action committees (PACs). These PACs can then contribute to federal elections, providing a legal avenue for corporate donations to influence political campaigns.

Super PACs, or independent expenditure-only committees, are a notable exception to the direct contribution prohibition. Super PACs can accept unlimited contributions from corporations, unions, associations, and individuals. They can then spend this money without limits to advocate for or against political candidates. This loophole allows corporations to exert significant influence on political campaigns, as long as they do not directly contribute to the candidates themselves.

In addition to federal regulations, state laws also govern corporate donations in state and local elections. These laws vary by state, and while some may mirror federal regulations, others may have looser or stricter rules. As a result, the landscape of campaign finance regulations can be complex, with corporations needing to navigate both federal and state laws when considering political contributions.

While these regulations aim to prevent corruption and undue influence, critics argue that they do not go far enough. They contend that loopholes, such as Super PACs, still allow corporations and special interest groups to exert outsized influence on political campaigns. On the other hand, proponents of fewer regulations argue that strict disclosure requirements and donation limits infringe upon privacy and free expression rights, hindering participation in the political process.

Political Campaigns and PACs: Separate Entities?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 is a federal law that regulates campaign finance. It is enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and limits the amount of money individuals and organisations can donate to a candidate running for federal office. It also requires candidates to disclose the sources of their campaign contributions and expenditures.

The FEC is an independent regulatory agency established in 1975 to enforce the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971. The FEC's mission is to protect the integrity of the federal campaign finance process by providing transparency and enforcing federal campaign finance laws.

There are two main types of contributions: "hard money" and "soft money". Hard money refers to regulated contributions from individuals, PACs, or parties committees to a federal candidate or other PACs for a federal election. Soft money is used for "mixed-purpose" activities not directly related to a specific candidate's election or defeat, such as get-out-the-vote drives and generic party advertising.

Super PACs, or independent expenditure-only committees, can raise and spend unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, associations, and individuals. They must file regular reports with the FEC disclosing their receipts and disbursements but are not bound by contribution limits.

Candidates can spend their own personal funds on their campaigns without limits. However, they must report the amount they spend to the FEC. Additionally, in 1996, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress could not restrict the total amount of "independent expenditures" made by a political party without coordination with a candidate, effectively allowing parties and candidates to circumvent FECA's contribution limits.