The concept of political parties flipping refers to the historical shift in the United States when the Democratic and Republican parties essentially swapped their ideological positions and voter bases. This transformation, often referred to as the party realignment, occurred primarily during the mid-20th century, with the most significant changes taking place in the 1960s. Before this period, the Democratic Party was largely associated with conservative, Southern interests, while the Republican Party was more aligned with progressive and Northern ideals. However, the Civil Rights Movement and the subsequent passage of landmark legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 catalyzed a dramatic shift. Southern conservatives, who had traditionally supported the Democratic Party, began to align with the Republican Party, which increasingly embraced states' rights and conservative policies. Conversely, the Democratic Party became the primary advocate for civil rights and progressive social policies, attracting a more liberal voter base. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, this realignment was largely complete, fundamentally altering the political landscape of the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Year of Party Flip | Late 19th to early 20th century (primarily completed by the 1930s) |

| Key Event | Southern states shifted from Democratic to Republican dominance |

| Primary Cause | Civil Rights Movement and Democratic support for racial equality |

| Geographic Focus | Southern United States (e.g., Deep South and border states) |

| Political Figures | Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon (Southern Strategy) |

| Impact on Parties | Democrats became more liberal; Republicans gained conservative base |

| Modern Alignment | Republicans dominate the South; Democrats dominate urban and coastal areas |

| Historical Context | Post-Reconstruction era and Jim Crow laws |

| Long-Term Effect | Polarization of U.S. politics along regional and ideological lines |

| Notable Elections | 1964 (Civil Rights Act), 1968 (Nixon's Southern Strategy) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Party Flip: Early 1800s, Democratic-Republicans and Federalists shifted, laying groundwork for future changes

- Civil War Impact: Post-1865, Southern Democrats became Republicans, Northern Republicans turned Democrats

- New Deal Era: 1930s, FDR’s policies realigned parties, solidifying Democrats as progressive, Republicans conservative

- Civil Rights Shift: 1960s, Southern Democrats moved to GOP over racial policies, flipping regional dominance

- Modern Polarization: Post-1990s, ideological divides deepened, parties became more distinct and adversarial

Origins of Party Flip: Early 1800s, Democratic-Republicans and Federalists shifted, laying groundwork for future changes

The early 1800s marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as the Democratic-Republicans and Federalists began a transformation that would lay the groundwork for future party realignments. This period, often overlooked, is crucial for understanding the origins of the party flip phenomenon. The Democratic-Republicans, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson, initially championed states' rights and agrarian interests, while the Federalists, under Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government and industrial growth. However, by the 1820s, these distinctions began to blur, as issues like westward expansion and the role of the federal government in economic development reshaped political alliances.

To illustrate, consider the Missouri Compromise of 1820, a key event that exposed fractures within both parties. Democratic-Republicans from the North and South clashed over the issue of slavery in new states, while Federalists struggled to maintain relevance in a rapidly changing political landscape. This compromise temporarily resolved the issue but highlighted the growing divide within the Democratic-Republican Party, which would later split into the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. The Federalists, meanwhile, faded into obscurity, their decline accelerated by their inability to adapt to emerging national concerns.

Analyzing this shift reveals a critical lesson: party identities are not static but evolve in response to societal and economic changes. The early 1800s demonstrated that when parties fail to address new issues or adapt to shifting demographics, they risk fragmentation or obsolescence. For instance, the Democratic-Republicans’ internal divisions over slavery and economic policies foreshadowed the eventual rise of the Republican Party in the 1850s. This period underscores the importance of flexibility and responsiveness in political organizations.

A comparative perspective further illuminates the significance of this era. Unlike later party flips, such as the post-Civil War realignment or the mid-20th-century shift of the South from Democratic to Republican, the early 1800s changes were more gradual and less tied to a single cataclysmic event. Instead, they were driven by a series of incremental shifts in ideology and coalition-building. This makes the period a unique case study in how political parties can transform organically, setting a precedent for future realignments.

For those interested in understanding modern political dynamics, studying this era offers practical insights. First, track how parties respond to emerging issues—whether it’s climate change, technological advancements, or economic inequality. Parties that fail to address these concerns risk alienating voters, much like the Federalists did in the 1820s. Second, observe coalition-building strategies. The Democratic-Republicans’ ability to unite diverse interests initially gave them an advantage, but their eventual splintering shows the challenges of maintaining such coalitions over time. Finally, recognize that party flips are not sudden but are often the culmination of decades of gradual change, rooted in earlier shifts like those of the early 1800s.

Mike Bloomberg's Political Party Affiliation: Unraveling His 2020 Campaign Platform

You may want to see also

Civil War Impact: Post-1865, Southern Democrats became Republicans, Northern Republicans turned Democrats

The American Civil War (1861–1865) reshaped the nation’s political landscape in ways that defy modern party alignments. Post-1865, the Democratic Party, once dominant in the slaveholding South, began to fracture. Southern Democrats, who had championed states’ rights and agrarian interests, found themselves at odds with the Republican Party’s Reconstruction policies, which aimed to protect the rights of freed slaves and rebuild the South under federal oversight. This ideological clash set the stage for a dramatic realignment. By the late 19th century, many Southern Democrats, disillusioned with Republican dominance, began to shift their allegiance, though the full flip would take decades to materialize.

To understand this transition, consider the role of the Solid South. From the 1870s to the 1960s, the South remained staunchly Democratic, a reaction to the Republican Party’s association with Reconstruction and Northern industrial interests. However, the seeds of change were sown during this period. As the national Democratic Party embraced progressive policies and civil rights in the mid-20th century, Southern Democrats felt increasingly alienated. Meanwhile, the Republican Party, once the party of Lincoln and abolition, began courting Southern voters by emphasizing states’ rights and economic conservatism. This ideological convergence laid the groundwork for the eventual flip.

The tipping point came during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 alienated many Southern Democrats, who viewed these measures as federal overreach. In contrast, Republicans like Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon capitalized on Southern discontent through the “Southern Strategy,” appealing to voters opposed to racial integration and federal intervention. By the 1980s, the South had largely flipped to Republican control, while Northern Republicans, increasingly aligned with urban and progressive interests, began drifting toward the Democratic Party.

This realignment was not merely a geographic shift but a fundamental reordering of party ideologies. The Republican Party, once the champion of abolition and federal authority, became the party of states’ rights and social conservatism in the South. Conversely, the Democratic Party, once the defender of Southern agrarian interests, evolved into the party of civil rights and federal activism. Practical examples abound: states like Texas and Georgia, solidly Democratic in the early 20th century, are now Republican strongholds, while Northern states like Massachusetts and Illinois have become reliably Democratic.

In conclusion, the Civil War’s impact on party realignment was neither immediate nor linear, but its echoes are unmistakable. The flip was driven by a complex interplay of race, economics, and regional identity, culminating in the modern political divide. For those studying political history or seeking to understand contemporary partisanship, this post-1865 transformation offers a critical lens. It underscores how historical events can reshape ideologies and alliances, leaving a legacy that endures over a century later.

Do Political Parties Still Matter to American Voters Today?

You may want to see also

New Deal Era: 1930s, FDR’s policies realigned parties, solidifying Democrats as progressive, Republicans conservative

The 1930s marked a seismic shift in American politics, as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies not only reshaped the nation’s economic landscape but also permanently realigned the political parties. Before this era, the Democratic Party was largely associated with agrarian interests and limited government intervention, while the Republican Party championed business and industrial growth. However, the Great Depression demanded bold federal action, and FDR’s expansive programs—such as Social Security, the Works Progress Administration, and the National Recovery Administration—repositioned the Democrats as the party of progressive reform. This transformation was not merely ideological but also demographic, as the New Deal coalition drew in labor unions, urban voters, African Americans, and Southern whites, creating a broad base of support for Democratic policies.

To understand the mechanics of this realignment, consider the strategic appeal of the New Deal to diverse constituencies. For urban workers, programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps provided jobs and relief. For farmers, the Agricultural Adjustment Act offered financial stability. For the elderly, Social Security promised a safety net. These policies were not just economic interventions but also moral commitments to fairness and opportunity, which resonated deeply with voters. Meanwhile, the Republican Party, initially resistant to such expansive federal programs, found itself increasingly associated with opposition to these popular reforms. This resistance solidified their image as the party of fiscal conservatism and limited government, a contrast that persists to this day.

A comparative analysis of the 1936 presidential election illustrates the extent of this realignment. FDR’s landslide victory, winning every state except Maine and Vermont, demonstrated the broad appeal of his progressive agenda. The election also marked a turning point for African American voters, who had historically aligned with the Republican Party due to its role in abolishing slavery. The New Deal’s inclusionary policies, coupled with the GOP’s perceived indifference to their struggles during the Depression, led to a significant shift in Black voters’ allegiance to the Democratic Party. This demographic shift was a critical component of the New Deal coalition and remains a defining feature of American politics.

However, the realignment was not without its challenges or critics. Some argued that the New Deal’s expansive federal programs overstepped constitutional boundaries, while others within the Democratic Party resisted the inclusion of marginalized groups, particularly in the South. Yet, despite these tensions, the New Deal era established a new political paradigm. It framed the Democrats as the party of active government intervention and social welfare, while the Republicans became the defenders of free markets and individualism. This ideological divide, born in the 1930s, continues to shape American political discourse.

For those studying or teaching this period, it’s essential to emphasize the long-term consequences of the New Deal realignment. Practical tips for understanding its impact include examining primary sources like FDR’s fireside chats, which humanized his policies, and analyzing voting patterns from the 1930s to the present. Additionally, comparing the New Deal to contemporary policy debates—such as healthcare reform or climate change initiatives—can highlight the enduring legacy of this era. By focusing on the specifics of FDR’s policies and their effects, one can grasp how the 1930s fundamentally altered the identities of the Democratic and Republican parties, setting the stage for modern American politics.

Party Loyalty vs. Issues: How Many Voters Prioritize Political Affiliation?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.96 $35

Civil Rights Shift: 1960s, Southern Democrats moved to GOP over racial policies, flipping regional dominance

The 1960s marked a seismic shift in American politics, as the Democratic Party's staunch support for civil rights legislation alienated many Southern conservatives. This ideological rift didn't happen overnight; it was a slow burn fueled by decades of racial tension and competing visions for the nation's future. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both championed by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson, became the tipping point. These landmark laws, while morally imperative, were seen by many Southern Democrats as federal overreach and a threat to their way of life.

Example: Strom Thurmond, a staunch segregationist and former Democratic governor of South Carolina, switched to the Republican Party in 1964, declaring, "The Democrats have abandoned the people."

This mass exodus wasn't merely a symbolic gesture. It represented a fundamental realignment of political power. The "Solid South," a reliably Democratic stronghold since Reconstruction, began to crumble. Republican strategists, recognizing the opportunity, actively courted these disaffected Southern Democrats, leveraging their opposition to civil rights and playing on fears of social change. This "Southern Strategy" proved remarkably effective, gradually transforming the South into a Republican bastion.

Analysis: The shift wasn't solely about race, though it was the primary catalyst. Economic anxieties and cultural conservatism also played a role. However, the GOP's willingness to capitalize on racial resentment was a key factor in their success.

The consequences of this flip were profound and long-lasting. The Democratic Party, once dominant in the South, found itself increasingly confined to urban centers and coastal states. The Republican Party, on the other hand, solidified its hold on the South, a region that would become crucial to their electoral success for decades to come. This realignment reshaped the political landscape, influencing everything from legislative priorities to the tone and tenor of national discourse.

Takeaway: The civil rights movement, while a triumph for justice and equality, also triggered a political earthquake. The Southern Democrats' defection to the GOP wasn't just a party switch; it was a fundamental reordering of American politics, with repercussions still felt today.

Mass-Based Party Politics: The Rise in Multi-Party Systems

You may want to see also

Modern Polarization: Post-1990s, ideological divides deepened, parties became more distinct and adversarial

The 1990s marked a turning point in American politics, setting the stage for the intense polarization we witness today. This era saw the beginnings of a shift where political parties moved from occasional cooperation to entrenched opposition, transforming the political landscape into a battleground of ideologies. The post-1990s period is characterized by a deepening of ideological divides, with parties becoming more distinct and adversarial, a trend that has only accelerated in recent decades.

The Rise of Partisan Media and Echo Chambers

One of the key drivers of modern polarization is the proliferation of partisan media outlets and the rise of social media. In the 1990s, cable news networks like Fox News and MSNBC began catering to specific ideological audiences, reinforcing existing beliefs rather than challenging them. By the 2000s, the internet and social media platforms created echo chambers where individuals were exposed primarily to information that aligned with their views. For example, a study by the Pew Research Center found that 64% of U.S. adults sometimes or often get their news from social media, where algorithms prioritize content that generates engagement, often at the expense of factual accuracy. This media environment has exacerbated polarization by reducing exposure to opposing viewpoints and fostering confirmation bias.

Legislative Gridlock and Partisan Identity

As ideological divides deepened, legislative cooperation became increasingly rare. The 1994 Republican Revolution, which gave the GOP control of Congress, marked the beginning of a more confrontational approach to governance. By the 2010s, tactics like the filibuster and government shutdowns became commonplace, paralyzing legislative progress. For instance, the 2013 government shutdown, driven by partisan disagreements over the Affordable Care Act, cost the U.S. economy an estimated $24 billion. This gridlock has reinforced partisan identities, with voters increasingly viewing politics as a zero-sum game where compromise is seen as betrayal.

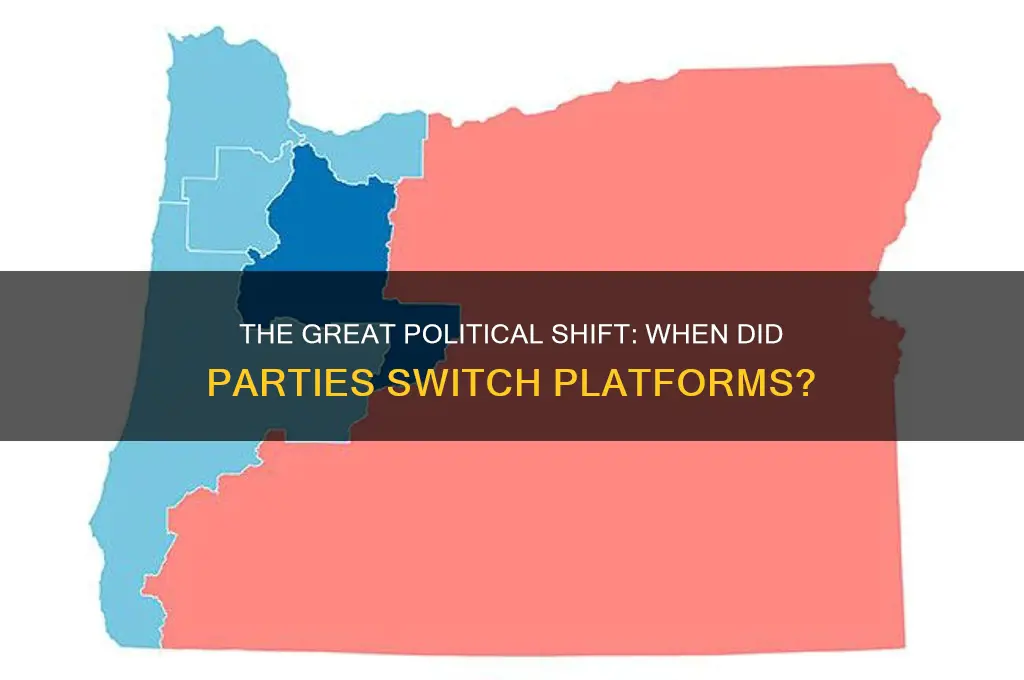

Geographic Sorting and Cultural Divides

Another factor in modern polarization is the geographic sorting of Americans into politically homogeneous communities. Since the 1990s, urban areas have become more liberal, while rural areas have grown more conservative. This trend is evident in voting patterns: in the 2020 election, 90% of counties with a population over 1 million voted Democratic, while 95% of rural counties voted Republican. This geographic divide is compounded by cultural differences, such as attitudes toward gun rights, abortion, and climate change. For example, a 2021 Gallup poll found that 80% of Republicans believe gun ownership makes the U.S. safer, compared to just 29% of Democrats. These cultural and geographic divides have made it harder for Americans to find common ground.

Practical Steps to Bridge the Divide

While the trends of polarization seem daunting, there are actionable steps individuals and institutions can take to mitigate its effects. First, diversify your media diet by seeking out news sources with differing perspectives. Tools like AllSides or Ground News can help identify the ideological leanings of outlets. Second, engage in constructive dialogue with those who hold opposing views, focusing on shared values rather than differences. For example, a study by the University of Pennsylvania found that structured conversations between Democrats and Republicans reduced partisan animosity by 20%. Finally, support institutions that foster bipartisanship, such as the Bipartisan Policy Center or No Labels, which work to find common ground on key issues. By taking these steps, individuals can play a role in reversing the tide of polarization.

Modern polarization is a complex phenomenon rooted in media, politics, and culture, but it is not insurmountable. Understanding its origins and taking proactive steps to bridge divides can help rebuild a more cooperative and functional political system.

The Origins of America's Political Parties: A Historical Journey

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The major political party realignment, often referred to as the "party flip," occurred primarily during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but the most significant shift happened in the 1960s and 1970s, when the Democratic and Republican parties largely switched their regional and ideological bases.

The flip was driven by several factors, including the Civil Rights Movement, the Southern Strategy, and shifting attitudes on social and economic issues. The Democratic Party's support for civil rights alienated many Southern conservatives, who moved to the Republican Party, while the GOP embraced more conservative policies.

The party flip reshaped the political landscape, with the Republican Party becoming dominant in the South and the Democratic Party strengthening its hold in urban and coastal areas. This realignment continues to influence modern political divisions and party platforms.