James Madison (1751–1836) played a pivotal role in drafting, explaining, and ratifying the US Constitution. He was also responsible for the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment, which guaranteed religious liberty, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press. Madison's words and actions defended the Constitution, and he is often referred to as the Father of the Constitution. He believed that the Constitution's meaning was fixed and determinate, defined by the objective meaning of its text, and not the subjective interpretations of its framers. Madison's advocacy for a just public opinion and his sustained attempts to solve the problem of majority opinion demonstrated his commitment to a form of government that was consistent with the spirit of popular government. He also advocated for constitutional principles of separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism, which would limit government and protect individual liberties.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Interpretation of the Constitution | Madison believed that the Constitution's meaning was fixed and determinate, defined by the objective meaning of the words at the time of its adoption. |

| Role in Drafting the Constitution | Madison played a pivotal role in drafting the Constitution, particularly through his Virginia Plan and his collaboration on The Federalist Papers. |

| Ratification of the Constitution | Madison was a key advocate for ratifying the Constitution as it was written, arguing against amendments prior to ratification. |

| Checks and Balances | Madison supported constitutional principles of separation of powers, checks and balances, bicameralism, and federalism to limit government and protect individual liberties. |

| Veto Power | Madison sought to include a federal veto on state laws to secure individuals' rights, but this proposal was ultimately unsuccessful. |

| Religious Liberty | Madison championed religious liberty, amending language in the Virginia Declaration of Rights and advocating for religious freedom in the Virginia Statute. |

| Bill of Rights | Madison introduced constitutional amendments that formed the basis of the Bill of Rights, though he opposed the idea of conditional amendments prior to ratification. |

| National Unity | Madison prioritized strengthening the Union over addressing slavery during the Constitutional Convention. |

| Historical Legacy | Madison is widely acclaimed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his contributions to its drafting and promotion. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Madison's view of the Constitution as a public document

James Madison (1751–1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who played a pivotal role in drafting, promoting, and defending the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights. He is often referred to as the "Father of the Constitution".

Madison believed that the Constitution was a public document, enacted by "We the People", and not by the Constitutional Convention. He argued that the Constitution's meaning was fixed and determinate, defined by the objective, public meaning of its words and phrases as they would have been understood by the political community at the time of its adoption. Madison once stated:

> the legitimate meaning of the Instrument must be derived from the text itself.

Madison's focus on the public meaning of the Constitution extended to his views on interpretation. He believed that the original meaning of the words and phrases of the document was what mattered, accounting for any well-understood specialised meanings or term-of-art understandings. He rejected the idea that the meaning of the Constitution's terms changed over time, stating:

> What a metamorphosis would be produced in the code of law if all its ancient phraseology were to be taken in its modern sense!

Madison's advocacy for a public understanding of the Constitution was also evident in his opposition to the inclusion of "conditional amendments" prior to ratification. He considered these amendments a "blemish" and believed that the Constitution should be ratified as it was written. Madison's expertise on the subject and rational arguments allowed him to respond effectively to Anti-Federalist appeals during the ratification process.

In his later years, Madison became highly concerned about his historical legacy and modified letters and documents in his possession. Despite these attempts to shape his legacy, Madison's contributions to the Constitution and his view of it as a public document remain a crucial part of his enduring impact on American political thought and history.

The Constitution's Emphasis on Freedom

You may want to see also

Madison's belief in the fixed, determinate meaning of the Constitution

James Madison is often referred to as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights. Madison's belief in the fixed, determinate meaning of the Constitution was a key aspect of his constitutional interpretation.

Madison viewed the Constitution as possessing a fixed, static, and determinate meaning on most matters. He believed that the meaning of the Constitution was defined by the objective meaning of the words of the text, rather than the subjective understandings of interpreters or the intentions of its framers. Madison asserted that the "meaning of the Instrument...must be derived from the text itself," and departures from this meaning were considered violations of the Constitution. This belief was reflected in his approach to constitutional interpretation, where he emphasised the original public meaning of the text over any subjective views or interpretations.

Madison's fixed interpretation of the Constitution was also evident in his opposition to the creation of a national bank, which he considered unconstitutional. He disagreed with Alexander Hamilton's claim that the Constitution granted "implied powers" to Congress and instead argued for a strict interpretation of the Constitution's express powers. Madison's belief in a fixed Constitution was further demonstrated in his work on the Virginia Declaration of Rights, where he replaced the phrase "all men should enjoy the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion" with "all men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise of it," a triumph that foreshadowed his later work on the Bill of Rights.

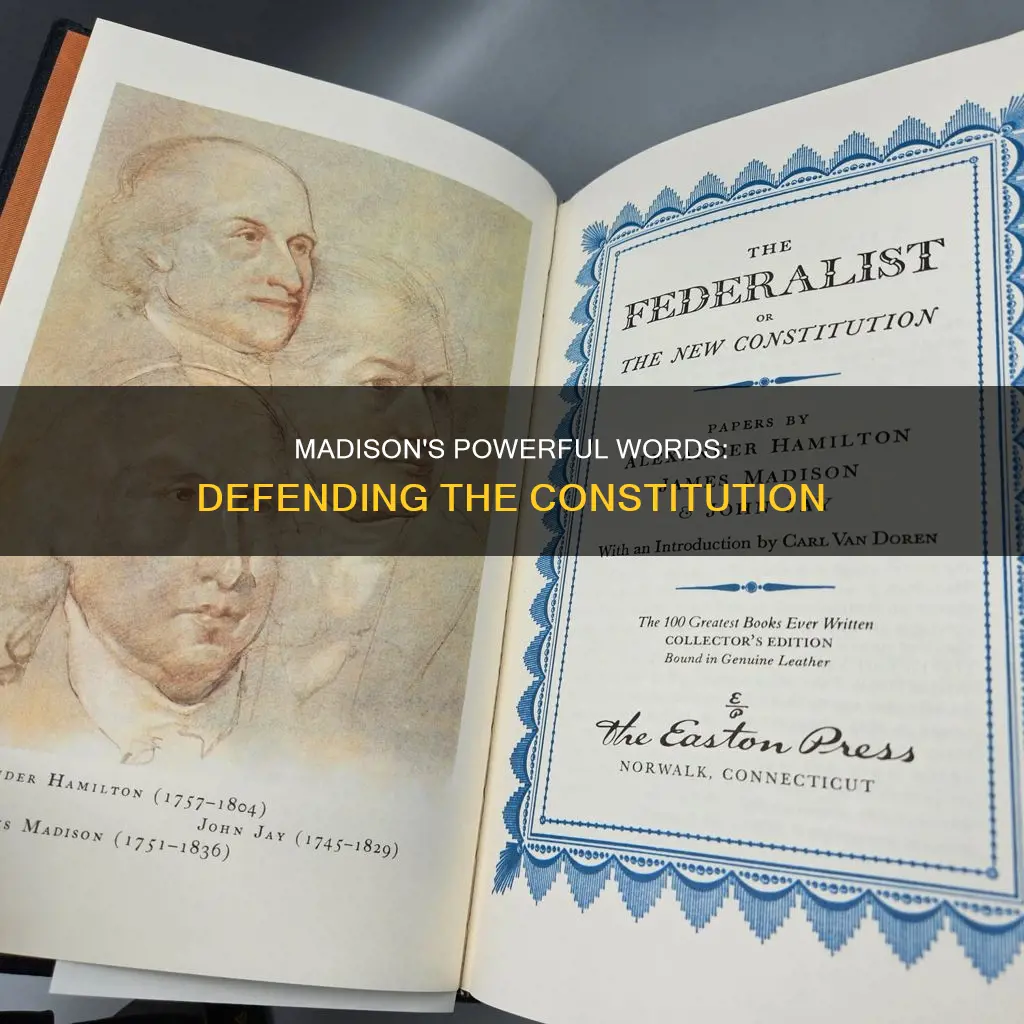

In addition to his role in drafting the Constitution, Madison also defended it through his contributions to The Federalist Papers, a series of pro-ratification essays written with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. These essays addressed concerns about the proposed federal government's size and responsiveness to the people. Madison's essay, Federalist No. 51, explained and defended the checks and balances system in the Constitution, demonstrating his commitment to preserving liberty and ensuring justice.

Exploring Election Years: Constitutional Basis and Beyond

You may want to see also

Madison's opposition to a bill of rights

James Madison, the chief drafter of the Bill of Rights, was initially opposed to the idea of adding a Bill of Rights to the US Constitution. In the early days of Anti-Federalist agitation, Madison had no way of knowing that his refusal to accept amendments would work in his favor so decisively. He feared that opening the debate up to amendments of a bill-of-rights sort could lead to alterations he did not want to consider at all. Madison believed that the Constitution was so well-crafted that it did not need any amendments. He also believed that a bill of rights would be less effective in securing the rights of the people than the structural protections provided by the constitutional order.

Madison also had other reasons for opposing a bill of rights. He believed that such documents were often just “parchment barriers” that overbearing majorities violated in the states regardless of whether written protections for minority rights existed. He also believed that a bill of rights would give the people too much authority. Madison also argued that the government could only exert the powers specified by the Constitution, and so a bill of rights was not necessary. He further contended that a bill of rights was unnecessary because the new federal government could in no way endanger the freedoms of the press or religion since it was not granted any authority to regulate either.

Despite his initial opposition, Madison eventually became a foremost advocate for adding a Bill of Rights to the Constitution. He realized that a bill of rights would cement the public's support for the Constitution and that many Americans remained suspicious that the Constitution's sponsors had been eager to establish a strong and potentially dangerous national government. He also wanted to quell the opposition of the Anti-Federalists to the new government by proposing a Bill of Rights in the First Congress. Madison was keenly aware that the Anti-Federalists were still calling for structural changes and a second constitutional convention to limit the powers of the national government and deny it power over taxation and the regulation of commerce. He feared this would lead to chaos and fought against it. He also sought greater consensus and harmony around constitutional principles by reaching out to the opponents of the new government.

Spanish Speaking Rights in New Mexico's Constitution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Madison's defence of federal veto rights

James Madison, the fourth president of the United States, is often referred to as the "Father of the Constitution" for his role in drafting and promoting the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. He was a strong advocate for federal veto rights and believed that the federal government should have the power to veto state laws.

In his defence of federal veto rights, Madison argued that the veto power was necessary to protect the executive branch from negative laws passed by the legislative branch that might encroach upon the powers of the executive. He also saw it as a final protection for the people against improper laws. Madison's view was that the Constitution had a fixed, determinate meaning that was defined by the objective meaning of the words of the text, rather than the subjective interpretations of those implementing it.

In his last official act as President, Madison vetoed the "Bonus Bill", which would have used profits from the National Bank to build roads and canals. Madison believed that building roads and canals was essential, but that it required a constitutional amendment to give Congress the authority to do so. He argued that the power to construct roads and canals was not expressly given to Congress by the Constitution and that interpreting the Constitution to give Congress such power would render the enumeration of powers in the Constitution "nugatory and improper".

The Judiciary: Constitutional Powers Explained

You may want to see also

Madison's role in the Virginia Plan

James Madison played a pivotal role in the creation and proposal of the Virginia Plan, a significant milestone in the formation of the United States government. The Virginia Plan, introduced at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, outlined Madison's vision for a strong national government.

Madison, a delegate from Virginia, believed that a robust central government was the solution to the problems facing the young nation. He drafted the Virginia Plan in anticipation of the Convention, consulting with members of the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations, including Virginia's governor, Edmund Randolph. While Madison is chiefly credited with producing the plan, Randolph contributed significantly and officially presented it to the Convention on May 29, 1787.

The Virginia Plan, also known as the Large-State Plan, proposed a national government consisting of three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. This structure aimed to address the lack of effective enforcement mechanisms in the existing Confederation government. The plan called for a bicameral legislature, divided into two bodies: the Senate and the House of Representatives, with representation based on population numbers. This feature of the plan set the agenda for debate at the Convention and highlighted the idea of population-weighted representation.

The plan's emphasis on a strong central government and its proposal for a bicameral legislature influenced the development of the U.S. Constitution. Madison's ideas were contrasted with those presented in the New Jersey Plan, which proposed a unicameral system where each state had a single vote, regardless of population size. The Virginia Plan's support for a strong national government and its provision favouring more populous states made it a preferred option for many delegates.

Religious Holiday Displays: Public Property, Constitutional?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Madison believed that the Constitution's meaning was fixed and determinate, defined by the objective meaning of the words of the text. He did not subscribe to the idea of unconstrained judicial discretion in constitutional interpretation.

Madison saw the Constitutional Convention as draftsmen of a proposal to be submitted to the people. He believed that the Constitution's meaning was derived from the text itself and not from the un-enacted, private "intentions" or subjective expectations of the framers.

Madison replaced the phrase "all men should enjoy the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion" with "all men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise of it." This reflected his strong support for religious liberty.

Madison argued that the federal government under the proposed Constitution would better protect the rights of individuals and minorities. He claimed that national legislation would be crafted by more political parties, making it difficult for any one faction to oppress minorities.

Madison was worried about the continuing strength of the Anti-Federalists, who were calling for structural changes and a second constitutional convention to limit the powers of the national government. He feared this would lead to chaos and fought against it.