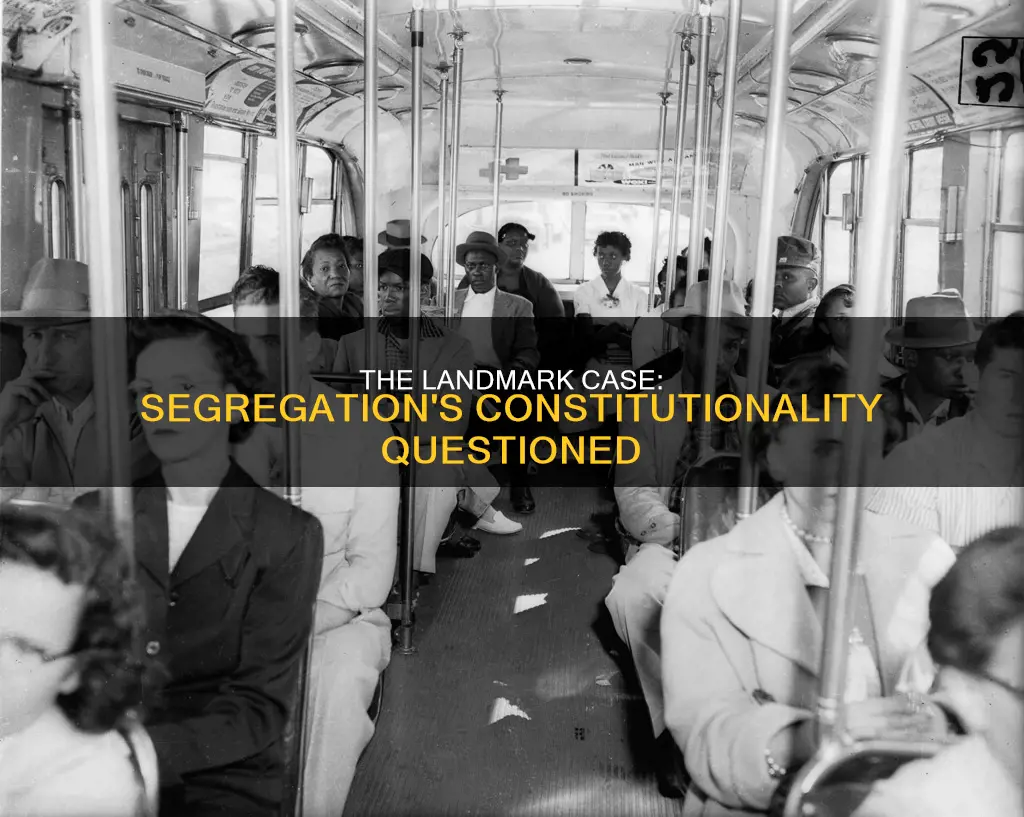

The case of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in public facilities, as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality. This “separate but equal” doctrine legitimized Jim Crow laws and led to the institutionalization of racial segregation that lasted into the 1960s. It was not until the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954 that segregation in public education was ruled unconstitutional, marking a turning point in the civil rights movement.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of the ruling | May 17,1954 |

| Case name | Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka |

| Court | U.S. Supreme Court |

| Decision | Unanimous |

| Decision details | Segregation in public education is unconstitutional and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment |

| Previous case overruled | Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) |

| Previous case decision | Racial segregation is constitutional as long as the separate facilities for the separate races were equal |

| Previous case vote | 7-1 |

| Previous case dissenting opinion author | Justice John Marshall Harlan |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

The case of Brown v. Board of Education began in 1951 as a class action lawsuit filed by 13 African American parents, including Oliver Brown, against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The lawsuit challenged the city's policy of racial segregation in public schools, which required children to attend schools based on their race. Oliver Brown's daughter, Linda Brown, was refused admission to an all-white secondary public school, prompting the lawsuit. The case combined five similar cases from Kansas, Delaware, Virginia, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia, all challenging segregation in public education.

The Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education was a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement. It signaled the end of legalized racial segregation in US schools and paved the way for integration. The Court's ruling stated that segregation in public education violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal protection of the laws to all US citizens. This ruling set a precedent for future impact litigation cases and influenced race relations, criminal justice, political processes, and the separation of church and state.

While the decision was celebrated by minority groups and civil rights activists, it faced criticism from some constitutional scholars who believed the Court had overstepped its powers by relying on data from social scientists rather than legal precedent. The absence of a specific plan for implementing the ruling also posed challenges, and further arguments were needed to determine how the decision would be enforced. Nonetheless, the Brown v. Board of Education case stands as a pivotal moment in US history, marking a step towards equality and justice for African Americans and shaping race relations for years to come.

DCBN Constitution: Fundamentals of Constitutionalism

You may want to see also

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

Plessy's attorneys argued that the state's segregation laws violated his rights under the Thirteenth Amendment, which prohibits slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal rights and protection to all U.S. citizens. However, the Supreme Court rejected these arguments, ruling that as long as the separate facilities for the separate races were equal, segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. This decision institutionalized Jim Crow laws, allowing racial segregation to persist for decades.

The lone dissenter in the Plessy case, Justice John Marshall Harlan, wrote a scathing dissent, predicting that the ruling would become as infamous as the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which denied citizenship to African Americans. Justice Harlan asserted that the Constitution is colour-blind and does not tolerate classes among citizens. Despite this dissent, the Plessy decision stood as the law of the land until it was finally overturned in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954.

The Brown v. Board case combined five similar cases from various states, challenging segregation in public schools. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favour of the plaintiffs, finding that segregation in public education was unconstitutional and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This ruling served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement and paved the way for integration in the United States.

The Constitution's Basic Framework Explained

You may want to see also

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

The Supreme Court's decision, delivered by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, stated that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and thus could not expect protection from the federal government or the courts. The Court also ruled that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from federal territories and that the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which declared all territories north of latitude 36°30′ as slave-free, was unconstitutional. This decision, made by a vote of 7-2, effectively moved the nation closer to the Civil War.

The Dred Scott decision was later overturned by the 13th and 14th Amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and declared all persons born in the United States as citizens. The case set a precedent for future Supreme Court rulings on racial segregation, such as Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which upheld the constitutionality of state laws requiring segregation in public facilities. However, the Plessy decision was later criticised by Justice John Marshall Harlan, who compared it to the infamous Dred Scott ruling. It was not until 1954, with the Brown v. Board of Education case, that the Supreme Court unanimously ruled to end segregation in public education, marking a significant step towards equality and justice for African Americans.

The President's Pardon Power: What's the Legal Basis?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents

The case of McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950) was a United States Supreme Court case that prohibited racial segregation in state-supported graduate or professional education. The plaintiff, George W. McLaurin, a Negro citizen of Oklahoma, already had a master's degree in education and was seeking a doctorate in education from the University of Oklahoma. At the time, Oklahoma law prohibited schools from instructing blacks and whites together.

McLaurin was admitted to the university and permitted to use the same classroom, library, and cafeteria as white students. However, pursuant to state law, he was subjected to segregation within these spaces. He was assigned a seat in a specific row for Negro students in the classroom, a special table in the library, and a separate table in the cafeteria.

McLaurin filed a complaint alleging that the actions of the school authorities and the state laws upon which they were based were unconstitutional and deprived him of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously held that the differential treatment given to McLaurin violated the Fourteenth Amendment, impairing his ability to study, engage in discussions, and exchange views with other students.

This case, along with Sweatt v. Painter, decided on the same day, marked the end of the "separate but equal" doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which had allowed racial segregation in public facilities to continue for decades. The McLaurin case specifically addressed segregation in graduate and professional education, signaling that the Supreme Court would no longer tolerate any separate treatment of students based on race.

Driverless Cars: Constitutional Impact

You may want to see also

Keys v. Interstate Commerce Commission (1955)

In 1952, Sarah Keys, an African-American woman and member of the Women's Army Corps (WAC), was travelling by bus from New Jersey to her hometown of Washington, North Carolina. At the Roanoke Rapids Trailways terminal, a new driver ordered her to move from her seat to the back of the bus in deference to a white Marine. Keys refused and was arrested on disorderly conduct charges. The North Carolina court system supported the arrest.

Keys and her father brought the case to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, who assigned the case to Dovey Johnson Roundtree, a former African-American WAC herself. Roundtree and her law partner, Julius Winfield Robertson, sued both Carolina Trailways and the Northern company from which Keys had bought her ticket.

On September 1, 1953, the US District Court for the District of Columbia dismissed the Keys complaint on jurisdictional grounds. Roundtree and Robertson then brought their case before the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), believing that it might be persuaded to re-evaluate its interpretation of the Interstate Commerce Act, just as the Supreme Court was then re-evaluating its interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In 1955, the ICC ruled in favour of Keys, stating:

> We conclude that the assignment of seats in interstate buses, so designated as to imply the inherent inferiority of a traveler solely because of race or color, must be regarded as subjecting the traveler to unjust discrimination, and undue and unreason [sic]

The ruling interpreted the non-discrimination language of the Interstate Commerce Act as banning the segregation of Black passengers in buses travelling across state lines. It applied the logic used in the United States Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education (1954) case, which had ended segregation in schools, to interstate transportation. The Keys v. Carolina Coach Company case was a landmark ruling that helped end racial segregation in interstate transportation.

The Supreme Court: Our Founding Fathers' Vision

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The case was brought about by Homer Plessy, a man who was 7/8ths white and 1/8th black, who challenged a Louisiana law that segregated railroad cars. The Supreme Court ruled in favour of the law, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in public facilities.

The Supreme Court ruled by a 7-1 margin that "separate but equal" public facilities could be provided to different racial groups. This decision enabled state-sanctioned segregation to remain in place for decades.

The Plessy decision institutionalised Jim Crow laws, which allowed racial segregation to continue for decades. The "separate but equal" doctrine permitted states to have separate facilities for different races as long as they were considered equal.

The Brown v. Board of Education case was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case that ruled racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. The case was brought by 13 African American parents on behalf of their children, who were being segregated in public schools.

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that segregation in public education was unconstitutional, overturning the Plessy v. Ferguson decision. The Court stated that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal".