The political rivalry between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, two of America’s Founding Fathers, was deeply rooted in their differing visions for the young nation. Adams, a Federalist, championed a strong central government, believed in a hierarchical social order, and favored close ties with Britain. In contrast, Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, advocated for states’ rights, agrarian democracy, and alignment with France. Their ideological clash during the 1790s and early 1800s not only defined the early American political landscape but also set the stage for the emergence of the first political parties in the United States, shaping the nation’s future governance and political discourse.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| John Adams' Party | Federalist Party |

| Thomas Jefferson's Party | Democratic-Republican Party |

| Ideological Focus | Adams: Strong central government, pro-commerce, pro-British |

| Jefferson: States' rights, agrarianism, pro-French | |

| Economic Policies | Adams: Supported industrialization and tariffs |

| Jefferson: Favored agriculture and opposed centralized banking | |

| Foreign Policy | Adams: Neutrality but leaned toward Britain |

| Jefferson: Supported France and opposed British influence | |

| Key Legislation | Adams: Alien and Sedition Acts |

| Jefferson: Louisiana Purchase, reduction of national debt | |

| Support Base | Adams: Urban merchants, New England elites |

| Jefferson: Farmers, Southern and Western states | |

| Philosophical Influence | Adams: Enlightened conservatism |

| Jefferson: Liberalism, natural rights, and limited government | |

| Legacy | Adams: Laid groundwork for strong federal institutions |

| Jefferson: Championed democracy and individual liberties |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Federalist Party: Adams' party, favored strong central government, supported by merchants, bankers, and New England elites

- Democratic-Republican Party: Jefferson's party, advocated states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal power

- Election of 1800: Adams (Federalist) vs. Jefferson (Democratic-Republican), a bitter and divisive contest

- Ideological Differences: Federalists (nationalism) vs. Democratic-Republicans (republicanism and individual liberties)

- Legacy and Impact: Shaped early U.S. politics, established two-party system, and defined political ideologies

Federalist Party: Adams' party, favored strong central government, supported by merchants, bankers, and New England elites

The Federalist Party, led by John Adams, emerged as a pivotal force in early American politics, championing a vision of a robust central government. This stance was not merely ideological but deeply rooted in the economic and social interests of its primary supporters: merchants, bankers, and the elite of New England. These groups saw a strong federal authority as essential for fostering commerce, stabilizing the economy, and maintaining order in a rapidly expanding nation.

Consider the context of the late 18th century. The United States, freshly independent, faced challenges such as state debts, trade disputes, and internal divisions. Federalists argued that only a centralized government could address these issues effectively. For instance, they supported the creation of a national bank, proposed by Alexander Hamilton, to regulate currency and credit. This institution was particularly beneficial to bankers and merchants, who relied on financial stability for their livelihoods. Similarly, Federalists favored tariffs and treaties that protected domestic industries, aligning with the interests of New England’s commercial class.

However, the Federalist Party’s emphasis on central authority was not without controversy. Critics, notably Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, accused them of undermining states’ rights and favoring the wealthy elite. The Federalists’ support for measures like the Alien and Sedition Acts further alienated those who valued individual liberties and local autonomy. Yet, for their core constituency, these policies were seen as necessary to safeguard the nation’s integrity and economic prosperity.

To understand the Federalist Party’s appeal, examine its regional focus. New England, with its thriving ports and burgeoning industries, stood to gain the most from federal policies. Merchants in Boston and bankers in Providence viewed a strong central government as a bulwark against chaos and a catalyst for growth. In contrast, agrarian regions in the South and West, where Jefferson’s party found its base, were skeptical of such concentration of power. This regional divide highlights how the Federalist Party’s agenda was tailored to the specific needs and aspirations of its supporters.

In practical terms, the Federalist Party’s legacy offers lessons for modern political movements. By aligning policy goals with the interests of key constituencies, they demonstrated the power of targeted advocacy. However, their downfall also serves as a cautionary tale: overemphasis on centralization and elitism can alienate broader segments of the population. For anyone studying political strategy, the Federalists’ rise and fall underscore the importance of balancing ideological vision with inclusivity. Their story reminds us that while a strong government can drive progress, it must also reflect the diverse needs of its people.

Understanding Emmanuel Macron's Political Affiliation: La République En Marche!

You may want to see also

Democratic-Republican Party: Jefferson's party, advocated states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal power

The Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the late 18th century, emerged as a direct response to the Federalist Party led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. This party, often referred to as Jefferson’s party, championed a vision of America rooted in states’ rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal power. At its core, the Democratic-Republican Party sought to counter what it perceived as the Federalist overreach in centralizing authority and favoring industrial and financial elites. By advocating for a decentralized government, Jefferson and his allies aimed to protect the liberties of individual states and the rural, farming majority that constituted the nation’s backbone.

To understand the Democratic-Republican Party’s appeal, consider its focus on agrarian interests. Jefferson idealized the yeoman farmer as the cornerstone of American democracy, believing that self-sufficient farmers were more likely to uphold republican virtues than urban merchants or bankers. This emphasis on agriculture was not merely ideological but practical, as the majority of Americans at the time were engaged in farming. The party’s policies, such as opposing tariffs that burdened Southern and Western farmers and resisting the establishment of a national bank, were designed to safeguard the economic interests of this demographic. For modern readers, this serves as a reminder that political movements often succeed by aligning with the material concerns of their constituents.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists. While the Federalists supported a strong central government, national economic policies, and close ties with Britain, Jefferson’s party favored states’ rights, strict interpretation of the Constitution, and diplomatic neutrality. This ideological divide was not merely academic; it shaped critical decisions, such as Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase, which expanded the nation’s agrarian frontier despite constitutional ambiguities. Such actions underscore the party’s willingness to prioritize its principles over rigid legalism, a strategy that both advanced its agenda and sparked debates about the balance of power in the young republic.

For those studying early American politics, the Democratic-Republican Party offers a cautionary tale about the challenges of balancing unity and diversity in a federal system. While its advocacy for states’ rights and agrarian interests resonated with many, it also contributed to regional divisions that would later escalate into the Civil War. Modern policymakers can draw lessons from this history: decentralization can empower local communities, but it must be balanced with mechanisms to ensure national cohesion. Practical steps, such as fostering dialogue between federal and state authorities and designing policies that address both urban and rural needs, can help navigate this tension effectively.

In conclusion, the Democratic-Republican Party’s legacy lies in its bold reimagining of American governance. By championing states’ rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal power, Jefferson’s party not only shaped the political landscape of its time but also left enduring questions about the role of government in a diverse society. Its successes and shortcomings remind us that political ideologies, while powerful, must be continually reassessed to meet the evolving needs of a nation. For historians, educators, and citizens alike, the Democratic-Republican Party remains a vital case study in the complexities of democracy.

Political Influence on Judicial Interpretation of Constitutional Law

You may want to see also

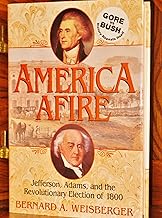

Election of 1800: Adams (Federalist) vs. Jefferson (Democratic-Republican), a bitter and divisive contest

The Election of 1800 stands as a pivotal moment in American history, marking the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing political parties. John Adams, the incumbent Federalist president, faced off against Thomas Jefferson, the leader of the Democratic-Republican Party. This contest was not merely a battle of ideologies but a bitter, deeply personal struggle that exposed the fragilities of the young nation’s political system. At its core, the election was a clash between two visions for America: Adams’ centralized, industrial future versus Jefferson’s agrarian, states’ rights ideal.

To understand the divisiveness, consider the tactics employed. Federalists painted Jefferson as an atheist and radical, claiming his election would lead to chaos and moral decay. Democratic-Republicans, in turn, portrayed Adams as a monarchist bent on undermining democracy. Newspapers, the primary medium of the era, became battlegrounds of slander and misinformation. For instance, the *Aurora General Advertiser*, a Democratic-Republican paper, accused Adams of being a "repulsive pedant," while Federalist publications labeled Jefferson a "howling atheist." This toxic rhetoric polarized the electorate, making compromise nearly impossible.

The election’s mechanics further exacerbated tensions. Under the original Electoral College system, each elector cast two votes, with the winner becoming president and the runner-up vice president. Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, tied with 73 electoral votes, throwing the election to the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives. For 36 ballots, Federalists blocked Jefferson’s victory, fearing his party’s rise. Only after Alexander Hamilton’s intervention, who distrusted Burr’s ambition, did Jefferson secure the presidency. This deadlock exposed the flaws in the electoral system, leading to the 12th Amendment’s ratification in 1804.

The takeaway from this bitter contest is twofold. First, it demonstrated the resilience of American democracy, as the nation survived a contentious election without descending into violence. Second, it highlighted the dangers of partisan extremism and the need for institutional safeguards. The Election of 1800 serves as a cautionary tale, reminding modern voters that divisive rhetoric and procedural vulnerabilities can threaten the very foundations of governance. To avoid such crises, citizens must prioritize informed discourse over partisan loyalty and support reforms that strengthen electoral integrity.

Nazis' Political Spectrum: Unraveling Their Extreme Right-Wing Ideology

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.41 $19

Ideological Differences: Federalists (nationalism) vs. Democratic-Republicans (republicanism and individual liberties)

The late 18th century in the United States was marked by a profound ideological divide between the Federalists, led by figures like John Adams, and the Democratic-Republicans, championed by Thomas Jefferson. At the heart of this division was a clash between nationalism and republicanism, each side advocating for a distinct vision of America’s future. Federalists prioritized a strong central government, believing it essential for national stability and economic growth, while Democratic-Republicans championed decentralized power, individual liberties, and agrarian ideals. This tension was not merely academic; it shaped policies, alliances, and the very structure of the young nation.

Consider the Federalist vision: they advocated for a robust federal government, exemplified by Alexander Hamilton’s financial policies, such as the establishment of a national bank and the assumption of state debts. These measures aimed to consolidate economic power and foster industrial growth. Federalists viewed a strong central authority as a safeguard against chaos, ensuring unity and progress. For instance, the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, passed under Adams’s administration, reflected their willingness to curb dissent in the name of national security. This nationalist approach, however, alarmed many who feared it would undermine state sovereignty and individual freedoms.

In contrast, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans embraced republicanism, emphasizing local governance, agrarian society, and the protection of individual liberties. They saw the Federalist agenda as elitist and a threat to the common man’s rights. Jefferson famously declared, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” His party championed the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798–1799, which asserted states’ rights to nullify federal laws deemed unconstitutional. This ideological stance resonated with farmers and rural populations, who felt marginalized by Federalist policies favoring urban and commercial interests.

The practical implications of these differences were stark. Federalists supported tariffs and infrastructure projects to bolster industry, while Democratic-Republicans opposed such measures, arguing they disproportionately benefited the wealthy. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 exemplified this divide: Federalists criticized it as unconstitutional, while Jefferson, though initially hesitant, embraced it as an opportunity to expand agrarian democracy. These contrasting approaches highlight how ideology translated into tangible policy outcomes, shaping the nation’s trajectory.

In navigating this ideological rift, modern observers can draw lessons on the enduring tension between centralized authority and individual freedoms. The Federalist-Democratic-Republican debate underscores the importance of balancing national unity with local autonomy, a challenge still relevant today. By examining these historical perspectives, we gain insight into the roots of contemporary political divides and the complexities of governing a diverse society. Understanding this era reminds us that ideological differences, while divisive, are also the bedrock of democratic discourse.

Decoding Political Language: How Parties Craft Messages to Shape Public Opinion

You may want to see also

Legacy and Impact: Shaped early U.S. politics, established two-party system, and defined political ideologies

The rivalry between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, leaders of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, respectively, laid the groundwork for the two-party system that continues to dominate American politics. Their ideological clash over the role of government, economic policy, and individual liberties crystallized into distinct political platforms, offering voters clear choices and fostering a competitive political environment. This early polarization not only structured political discourse but also ensured that diverse perspectives were represented in governance, a principle that remains central to American democracy.

Consider the practical impact of their ideological divide: Adams’ Federalists advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, while Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans championed states’ rights, agrarianism, and alignment with France. These contrasting visions forced citizens to engage with fundamental questions about the nation’s identity and direction. For instance, the Federalist push for a national bank and protective tariffs directly opposed the Democratic-Republican emphasis on decentralized power and agrarian self-sufficiency. This ideological clarity made political participation more accessible, as voters could align themselves with a party based on tangible policy differences rather than abstract principles.

To understand their legacy, examine how their parties shaped political tactics. The election of 1800, a bitter contest between Adams and Jefferson, marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties in U.S. history. This set a precedent for democratic transitions, demonstrating that political rivals could compete fiercely yet respect the electoral process. However, the campaign also highlighted the dangers of partisan extremism, as both sides engaged in personal attacks and misinformation. Modern political operatives often study this election as a cautionary tale, balancing aggressive campaigning with the need to preserve institutional integrity.

A comparative analysis reveals how their ideologies continue to influence contemporary politics. Federalist priorities, such as federal authority and economic modernization, resonate in today’s conservative emphasis on national security and corporate interests. Conversely, Democratic-Republican ideals of local control and individual freedoms echo in modern progressive calls for grassroots democracy and social equity. This enduring divide underscores the parties’ role in defining political identities, with Americans still debating the balance between centralized power and individual autonomy.

Finally, their impact extends beyond policy to the very structure of political engagement. By establishing a two-party system, Adams and Jefferson created a framework that encourages coalition-building, compromise, and accountability. While this system has its flaws—often limiting third-party viability and exacerbating polarization—it has proven resilient, adapting to societal changes while maintaining core democratic functions. For those seeking to navigate today’s political landscape, understanding this legacy provides historical context for current debates and strategies for fostering constructive dialogue across ideological lines.

The National Party's Role in South Africa's Apartheid Regime

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

John Adams was a member of the Federalist Party, while Thomas Jefferson was a leader of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Adams and Jefferson belonged to different parties due to their contrasting views on the role of government, with Adams favoring a strong central government (Federalist) and Jefferson advocating for states' rights and limited federal power (Democratic-Republican).

The Federalists supported a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, while the Democratic-Republicans favored states' rights, agrarian interests, and closer relations with France.

Yes, Adams and Jefferson ran against each other in the 1796 and 1800 presidential elections. Adams won in 1796, and Jefferson won in 1800.

Their rivalry highlighted the ideological divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, shaping the two-party system and influencing debates over the Constitution, federal power, and foreign policy in early America.

![Earth Party! An Early Introduction to the Linnaean System of Classification of Living Things Unit Study [Teacher's Book]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61PqBE09giL._AC_UY218_.jpg)