The Declaration of Independence, formally The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America, is the founding document of the United States. It was adopted unanimously by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and explains why the Thirteen Colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British colonial rule. The Declaration is not divided into formal sections but is often discussed as consisting of five parts: introduction, preamble, indictment of King George III, denunciation of the British people, and conclusion. The preamble sought to inspire and unite Americans through the vision of a better life, stating the principles on which the government and identity of Americans are based.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of Declaration | July 4, 1776 |

| Author | Thomas Jefferson |

| Nature of the Document | Founding document of the United States |

| Legally Binding | No |

| Purpose | To explain why the Thirteen Colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British colonial rule |

| Target Audience | The King, the colonists, and the world |

| Main Points | All men are created equal; Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; Free and Independent States have the right to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. To secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly, all experience hath shown that mankind is more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.

Such has been the patient sufferance of these colonies, and such is now the necessity that constrains them to alter their former systems of government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over these states. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his assent to laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his governors to pass laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of representation in the legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved representative houses repeatedly, for opposing, with manly firmness, his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused, for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the legislative powers, incapable of annihilation, have returned to the people at large for their exercise, the state remaining, in the meantime, exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without and convulsions within. He has endeavored to prevent the population of these states, for that purpose obstructing the laws for naturalization of foreigners, refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new appropriations of lands. He has obstructed the administration of justice, by refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers. He has made judges dependent on his will alone, for the tenure of their offices and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of new offices, and sent hither swarms of officers to harass our people, and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, standing armies, without the consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the military independent of and superior to the civil power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution and unacknowledged by our laws, giving his assent to their acts of pretended legislation: for quartering large bodies of armed troops among us; for protecting them, by a mock trial, from punishment for any murders that they should commit on the inhabitants of these states; for cutting off our trade with all parts of the world; for imposing taxes on us without our consent; for depriving us, in many cases, of the benefits of trial by jury; for transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offenses; for abolishing the free system of English laws in a neighbouring province, establishing therein an arbitrary government, and enlarging its boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these colonies; for taking away our charters, abolishing our most valuable laws, and altering fundamentally the forms of our governments; for suspending our own legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated government here, by declaring us out of his protection and waging war against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is, at this time, transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to complete the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of cruelty and perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy of the head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow citizens taken captive on the high seas to bear arms against their country, to become the executioners of their friends and brethren, or to fall themselves by their hands. He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions. In every stage of these oppressions, we have petitioned for redress in the most humble terms; our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A prince, whose character is thus marked by every act that may define a tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have we been wanting in attention to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They, too, have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity that denounces our separation and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, enemies in war, in peace, friends.

We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the name and by the authority of the good people of these colonies, solemnly publish and declare that these united colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that, as free and independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do. And for the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honour.

People in the 15 Departments: How Long Are Their Terms?

You may want to see also

The right to dissolve political bands

The Declaration of Independence, formally "The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America", is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the Second Continental Congress, who convened in Philadelphia. The Declaration explains why the Thirteen Colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British colonial rule.

The inclusion of this right in the Declaration of Independence was influenced by the political philosophy of the time, particularly the ideas of the American Revolution. Thomas Jefferson, who drafted the Declaration, admitted that it contained no original ideas but was instead a statement of sentiments widely shared by supporters of the Revolution. The Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason in June 1776, also influenced Jefferson and included similar ideas and phrases.

The Athenian Constitution: A Historical Document of Governance

You may want to see also

The right to institute new governments

The Declaration of Independence, formally The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America, is the founding document of the United States. It was adopted unanimously on July 4, 1776, by the Second Continental Congress, who convened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Declaration explains why the Thirteen Colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British colonial rule.

Enlightenment Ideals: US Constitution's Core Principles

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The right to liberty and the pursuit of happiness

The Declaration of Independence, formally The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America, is the founding document of the United States. It was adopted unanimously by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and explained why the Thirteen Colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British colonial rule.

Congressional Powers Denied: Constitutional Limits Explored

You may want to see also

The right to levy war, conclude peace, and contract alliances

The Declaration of Independence, formally The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America, was adopted on July 4, 1776, by the Second Continental Congress, who convened in Philadelphia. The Declaration was authored by a committee comprising John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Sherman.

The Declaration is a powerful statement of the principles on which the US government and the identity of Americans are based. It is not legally binding but has had a profound influence on people around the world, inspiring them to fight for freedom and equality.

The right to "levy war, conclude peace, and contract alliances" is a critical component of the Declaration of Independence. This right is asserted in the context of declaring the independence of the thirteen colonies from Great Britain. The colonies were seeking to establish themselves as free and independent states, separate from British rule, and this right was essential for their sovereignty.

The right to levy war refers to the power of a sovereign state to engage in military conflict with another state. In the context of the Declaration, this meant that the colonies had the right to use military force to defend themselves against foreign enemies and assert their independence. This right was important as it signalled that the colonies were no longer subordinate to British military authority and could make their own decisions about engaging in war.

The right to conclude peace is the power to negotiate and enter into peace treaties with other states. This right is the corollary to the right to levy war, as it allows a state to formally end a military conflict and establish peaceful relations with another state. For the colonies, this right was crucial in asserting their ability to act independently and negotiate peace treaties without British control.

The right to contract alliances refers to the power of a state to form alliances or coalitions with other states for mutual benefit or protection. This right is significant as it allows states to establish diplomatic relations, seek support, and form strategic partnerships. By claiming this right, the colonies were signalling their intention to become active participants in international affairs and diplomacy, forming their own alliances rather than being bound by those made by Great Britain.

Together, these three rights form a crucial aspect of the colonies' assertion of independence and sovereignty. They represent the powers typically held by independent states and were essential for the colonies to act as a unified and autonomous political entity on the international stage.

The Constitution's Democracy Mentions: A Comprehensive Count

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

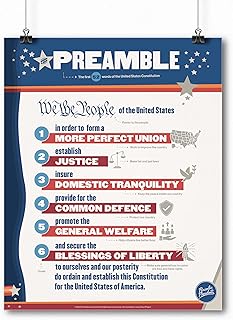

The Preamble of the Declaration of Independence is a statement of the principles on which the US government and the identity of Americans are based.

The Preamble includes the famous lines: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

No, the Preamble is not legally binding, unlike other founding documents.

The Preamble was designed to inspire and unite Americans through the vision of a better life. It was also meant to multitask and appeal to multiple audiences: the King, the colonists, and the world.

The Preamble was written by the Committee of Five: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Sherman.