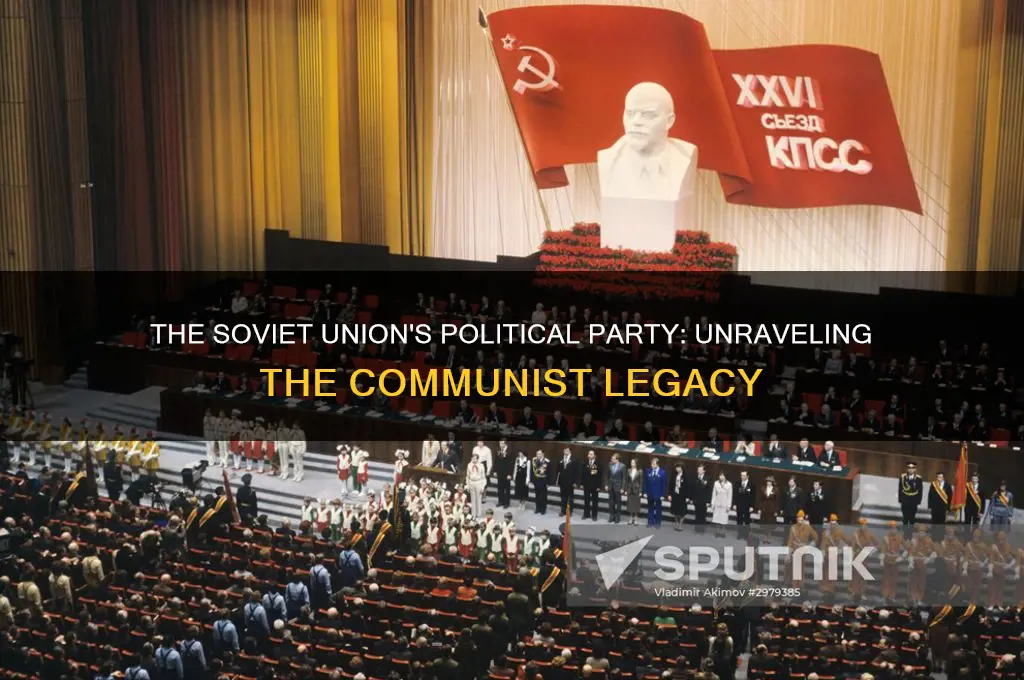

The Soviet Union, officially known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), was governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), which held a monopoly on political power from its inception in 1922 until its dissolution in 1991. Rooted in Marxist-Leninist ideology, the CPSU was the central institution of the Soviet state, controlling all aspects of political, economic, and social life. Its dominance was enshrined in the Soviet Constitution, which declared the Party the leading and guiding force of Soviet society. Under leaders like Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and later Mikhail Gorbachev, the CPSU shaped the USSR's policies, from rapid industrialization and collectivization to the Cold War and eventual reforms that led to its collapse. The Party's structure, with its Politburo and Central Committee, ensured tight control over the vast nation, making it the defining political entity of the Soviet era.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) |

| Ideology | Marxism-Leninism |

| Founded | 1912 (as the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party) |

| Dissolved | 1991 (banned following the dissolution of the Soviet Union) |

| Headquarters | Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Colors | Red |

| Symbol | Hammer and sickle |

| Anthem | "The Internationale" |

| Membership (peak) | Over 19 million (1986) |

| Role in Government | Sole ruling party under a one-party system |

| General Secretaries | Notable leaders include Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Leonid Brezhnev, and Mikhail Gorbachev |

| Political Position | Far-left |

| Economic Policy | State-controlled economy, centralized planning |

| International Affiliation | Comintern (1919–1943), Cominform (1947–1956) |

| Successor Parties | Various communist and socialist parties in post-Soviet states |

| Key Documents | The Communist Manifesto, State and Revolution, CPSU Party Program |

| Historical Significance | Central to the establishment and governance of the Soviet Union |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU): Dominant political party, Marxist-Leninist ideology, controlled government and society

- Role of CPSU: Centralized power, policy-making, leadership cult, and ideological enforcement

- Party Structure: Hierarchy from Politburo to local cells, ensuring control at all levels

- CPSU and State: Merged roles, party leadership dominated government institutions and decision-making

- Decline and Dissolution: Loss of authority, reforms, and eventual collapse in 1991

Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU): Dominant political party, Marxist-Leninist ideology, controlled government and society

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was the central force behind the Soviet Union's political, economic, and social structure from its inception in 1917 until its dissolution in 1991. As the dominant political party, the CPSU held a monopoly on power, effectively controlling all aspects of government and society. Its ideological foundation was rooted in Marxist-Leninist principles, which emphasized class struggle, the dictatorship of the proletariat, and the eventual establishment of a communist society. This ideology was not merely theoretical but served as the practical blueprint for the CPSU's governance, shaping policies, institutions, and daily life in the Soviet Union.

To understand the CPSU's dominance, consider its organizational structure. The party operated through a hierarchical system, with the Politburo at its apex, making key decisions that influenced the entire nation. Membership in the CPSU was both a privilege and a responsibility, as it granted access to political power and resources but also required strict adherence to party discipline. By the mid-20th century, the CPSU had over 19 million members, making it one of the largest political parties in history. This vast network ensured that the party's influence permeated every level of society, from local factories to the highest echelons of government.

The CPSU's control extended beyond politics into the realms of culture, education, and media. Through institutions like the Komsomol (Young Communist League) and state-controlled media outlets, the party disseminated its ideology and suppressed dissenting voices. For example, artists, writers, and intellectuals were expected to align their work with socialist realism, a style that glorified the working class and the achievements of the Soviet state. Deviations from this norm were often met with censorship or punishment, illustrating the CPSU's tight grip on societal expression.

A comparative analysis highlights the CPSU's uniqueness among political parties. Unlike multi-party systems in Western democracies, the CPSU operated within a one-party state, eliminating political competition. This structure allowed the party to implement sweeping reforms, such as the collectivization of agriculture and rapid industrialization, without the constraints of opposition. However, this concentration of power also led to inefficiencies, corruption, and a lack of accountability, ultimately contributing to the Soviet Union's decline.

In practical terms, the CPSU's dominance had profound implications for everyday life. Citizens were encouraged to participate in party-sponsored activities, such as parades and campaigns, to demonstrate loyalty. Education systems were designed to instill Marxist-Leninist values from a young age, ensuring ideological continuity. While the CPSU's control provided stability and a sense of purpose for many, it also stifled individual freedoms and innovation. For instance, career advancement often depended on party membership rather than merit, creating a system that rewarded conformity over creativity.

In conclusion, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was far more than a political organization; it was the architect and enforcer of a comprehensive ideological system. Its dominance, rooted in Marxist-Leninist principles, shaped every facet of Soviet society, from governance to culture. While the CPSU achieved significant milestones, such as rapid industrialization and the expansion of education, its rigid control and lack of accountability ultimately proved unsustainable. Understanding the CPSU's role offers valuable insights into the complexities of one-party rule and its enduring impact on history.

Political Parties: Shaping Governance, Policy, and National Leadership

You may want to see also

Role of CPSU: Centralized power, policy-making, leadership cult, and ideological enforcement

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was the central pillar of Soviet governance, wielding unparalleled authority over every facet of political, economic, and social life. Its role was not merely administrative but foundational, shaping the very identity of the Soviet state. At its core, the CPSU functioned as the embodiment of centralized power, a mechanism through which the state’s authority was concentrated and exercised. This centralization was not just structural but ideological, rooted in Marxist-Leninist principles that posited the Party as the vanguard of the proletariat. In practice, this meant that the CPSU monopolized decision-making, ensuring that no institution or individual could challenge its supremacy. From local soviets to the highest echelons of government, the Party’s directives were absolute, creating a system where power flowed unidirectionally from the CPSU to the masses.

Policy-making within the Soviet Union was synonymous with Party dictates. The CPSU’s Politburo, a select committee of top officials, served as the primary engine of policy formulation. Five-Year Plans, agricultural collectivization, and military strategies were not debated in open forums but crafted within the Party’s closed chambers. This process was deliberate and hierarchical, with lower Party organs implementing decisions handed down from above. For instance, the 1928 launch of the First Five-Year Plan, which prioritized rapid industrialization, was a direct outcome of CPSU policy. Local Party cells were tasked with mobilizing resources and labor, demonstrating how the CPSU’s centralized control translated into tangible, transformative policies. This top-down approach ensured uniformity but often stifled innovation and adaptability, as regional nuances were frequently overlooked.

The CPSU also cultivated a pervasive leadership cult, deifying figures like Lenin, Stalin, and later, Brezhnev. This cult was not merely symbolic but instrumental in consolidating the Party’s authority. Through propaganda, education, and public rituals, the leaders were portrayed as infallible, their images omnipresent in posters, statues, and textbooks. Stalin’s cult, in particular, reached unprecedented heights during the 1930s, with his name invoked in every sphere of life, from factories to farms. This personalization of power served a dual purpose: it legitimized the CPSU’s rule by associating it with revered figures, and it discouraged dissent by equating criticism of leadership with betrayal of the revolution. The cult’s psychological impact was profound, fostering a society where loyalty to the Party and its leaders was both a civic duty and a survival strategy.

Ideological enforcement was the CPSU’s final, and perhaps most insidious, tool for maintaining control. Marxism-Leninism was not just a guiding philosophy but a rigid dogma, enforced through institutions like the KGB and Party-controlled media. Deviation from orthodoxy was met with severe consequences, ranging from expulsion from the Party to imprisonment or worse. Intellectuals, artists, and even scientists were compelled to align their work with Party ideology, as seen in the suppression of abstract art and genetic research during the Stalin era. This ideological straitjacket ensured that the CPSU’s worldview remained unchallenged, but it also stifled creativity and critical thinking, contributing to the Soviet Union’s eventual stagnation. By controlling the narrative, the CPSU ensured that its version of reality was the only one that mattered, a tactic as effective as it was oppressive.

In conclusion, the CPSU’s role in the Soviet Union was multifaceted yet singular in purpose: to maintain absolute control. Through centralized power, it eliminated rivals; through policy-making, it shaped the nation’s trajectory; through the leadership cult, it legitimized its rule; and through ideological enforcement, it silenced dissent. These mechanisms were interdependent, forming a system where the Party’s authority was both omnipresent and unassailable. While the CPSU achieved remarkable feats, such as rapid industrialization and victory in World War II, its methods came at a steep cost, ultimately contributing to the Soviet Union’s demise. Understanding the CPSU’s role offers not just a window into Soviet history but a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked power and ideological rigidity.

Discover Politoed's Habitat: Best Locations to Catch This Rare Pokémon

You may want to see also

Party Structure: Hierarchy from Politburo to local cells, ensuring control at all levels

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was the ruling political party of the USSR, and its structure was designed to maintain tight control over the vast country. At the apex of this hierarchical system sat the Politburo, a powerful committee that made all significant decisions. This elite group, typically consisting of around 10 to 15 full members, was the epitome of political authority, with its members holding key positions in government, military, and state security. The Politburo's influence permeated every aspect of Soviet life, from economic planning to foreign policy, making it the ultimate arbiter of power.

The Hierarchy Unveiled:

Imagine a pyramid, with the Politburo at its pinnacle. Below this elite group was the Central Committee, a larger body of approximately 300 members, elected at party congresses. This committee served as a crucial link between the Politburo and the vast network of party organizations across the Soviet Union. Its primary role was to implement the policies decided by the Politburo, ensuring that the party's will was carried out at all levels. The Central Committee also played a key role in appointing officials and overseeing the work of various party departments, each responsible for specific areas like ideology, agriculture, or international relations.

As we descend further down the pyramid, we encounter the regional and local party committees, which formed the backbone of the CPSU's control mechanism. These committees, present in every republic, region, and district, were responsible for implementing central policies and maintaining party discipline. The local party boss, often referred to as the 'First Secretary', held immense power in their respective areas, controlling local government, industry, and media. This structure ensured that the party's influence reached every corner of the country, from the largest cities to the smallest rural communities.

Control and Compliance:

The CPSU's hierarchical structure was not just about organizational efficiency; it was a sophisticated system of control. Each level of the party hierarchy had its own set of responsibilities and reporting lines, creating a web of oversight and accountability. For instance, local party cells, the smallest units of the CPSU, were responsible for monitoring and guiding the activities of party members in factories, collective farms, and neighborhoods. These cells reported to higher-level committees, which in turn answered to the Central Committee and ultimately, the Politburo. This vertical integration ensured that any deviation from the party line could be quickly identified and rectified, maintaining ideological purity and political control.

In practice, this meant that a factory worker in Moscow or a farmer in Ukraine would be part of a local party cell, attending meetings, discussing party policies, and being evaluated on their commitment to the communist cause. Their cell leader would report to the district committee, which would then communicate with the regional and republic-level committees, all the way up to the Central Committee. This intricate system of reporting and supervision left little room for dissent or independent action, as every party member was accountable to someone higher up the chain.

The Power of Appointment:

A critical aspect of the CPSU's control was its power to appoint officials at all levels. The party's nomenklatura system gave it the authority to select and place individuals in key positions across government, industry, and public institutions. This ensured that only trusted party members occupied positions of influence, further solidifying the CPSU's grip on power. The process of appointment and promotion was carefully managed, with the Politburo and Central Committee playing a pivotal role in deciding who would lead various sectors of Soviet society.

In essence, the CPSU's hierarchical structure was a masterclass in political control, where every level of the party was interconnected and interdependent. From the all-powerful Politburo to the local party cells, this system ensured that the communist ideology and the party's authority were pervasive, leaving no room for alternative power centers to emerge. Understanding this structure provides valuable insights into how the Soviet Union was governed and how the CPSU maintained its dominance for over seven decades.

Dog Whistle Politics: Unveiling Hidden Messages in Modern Campaigns

You may want to see also

Explore related products

CPSU and State: Merged roles, party leadership dominated government institutions and decision-making

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was not merely a political party; it was the backbone of the Soviet state, with its roles so deeply intertwined that distinguishing between the two became nearly impossible. This fusion was codified in Article 6 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution, which declared the CPSU the "leading and guiding force of Soviet society and the nucleus of its political system." In practice, this meant that party leadership dominated every level of government institutions and decision-making, creating a system where the state existed to serve the party, and the party controlled the state.

Consider the structure of governance: key government positions, from ministers to local administrators, were held by CPSU members. The Politburo, the party’s highest decision-making body, effectively dictated state policy, while the Council of Ministers, nominally the executive branch, functioned as an implementer of party directives. This hierarchy was reinforced through the nomenklatura system, where the CPSU controlled appointments to thousands of positions across the state apparatus, ensuring loyalty and ideological alignment. The result was a monolithic system where party and state were not separate entities but two sides of the same coin.

To illustrate, the General Secretary of the CPSU, often referred to as the "leader of the party and the state," held more power than the Soviet president or premier. Figures like Joseph Stalin and Leonid Brezhnev exemplified this dominance, using their party positions to shape foreign policy, economic plans, and even cultural narratives. For instance, the Five-Year Plans, which dictated the Soviet economy, were drafted and approved by the CPSU Central Committee before being rubber-stamped by state institutions. This process highlights how the party’s ideological priorities consistently took precedence over bureaucratic or administrative considerations.

However, this merger of roles was not without tension. The dual loyalty required of officials—to both the state and the party—often led to inefficiencies and contradictions. While the CPSU’s dominance ensured ideological consistency, it stifled innovation and accountability. Local party bosses, for example, could override state regulations to meet party-imposed targets, leading to distortions in economic reporting and resource allocation. This dynamic underscores a critical takeaway: the CPSU’s control over the state was both its strength and its weakness, enabling centralized authority while fostering systemic rigidity.

In practical terms, understanding this merger is essential for analyzing the Soviet Union’s political legacy. It explains why reforms like Mikhail Gorbachev’s *perestroika* and *glasnost* ultimately destabilized the system: by challenging the CPSU’s dominance, they undermined the very foundation of the state. For modern observers, this serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of conflating party and state roles, as well as a reminder of the importance of institutional checks and balances in governance. The CPSU’s model was unique, but its lessons remain universally relevant.

Exploring the UK's Largest Political Party: Who Dominates British Politics?

You may want to see also

Decline and Dissolution: Loss of authority, reforms, and eventual collapse in 1991

The Soviet Union's political party, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), was the sole ruling party from its inception in 1917 until its dissolution in 1991. Its decline began with a series of internal contradictions and external pressures that eroded its authority. By the 1980s, economic stagnation, widespread inefficiency, and growing public discontent exposed the CPSU's inability to address systemic issues. Mikhail Gorbachev's introduction of *glasnost* (openness) and *perestroika* (restructuring) aimed to revitalize the system but instead accelerated its unraveling. These reforms, while intended to modernize the Soviet state, inadvertently empowered critics and exposed decades of corruption and mismanagement.

Consider the practical steps that led to this collapse. Gorbachev's reforms lifted censorship, allowing previously suppressed information to circulate freely. This transparency revealed the extent of the CPSU's failures, from the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 to chronic food shortages. Simultaneously, *perestroika* decentralized economic control, but without clear guidelines, it led to chaos rather than efficiency. Regional leaders began asserting autonomy, further weakening central authority. By 1990, the CPSU's monopoly on power was shattered as republics like Lithuania and Estonia declared independence, a direct challenge to Moscow's dominance.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between the CPSU's rigid ideology and the dynamic realities of the late 20th century. While the party clung to Marxist-Leninist principles, the global economy was shifting toward market-driven systems. The Soviet Union's inability to compete technologically or economically with the West exacerbated internal disillusionment. For instance, while the U.S. invested heavily in innovation during the 1980s, the USSR allocated a disproportionate share of its budget to military expenditures, neglecting civilian needs. This imbalance deepened public resentment and eroded faith in the CPSU's leadership.

Descriptively, the final years of the Soviet Union were marked by a palpable sense of disintegration. Strikes and protests became commonplace, with workers demanding better conditions and political reform. The August Coup of 1991, staged by hardline CPSU members opposed to Gorbachev's reforms, backfired spectacularly. It galvanized support for Boris Yeltsin and anti-communist forces, leading to the party's outright ban in Russia. On December 26, 1991, the Soviet Union officially dissolved, marking the end of the CPSU's seven-decade reign.

Instructively, the CPSU's collapse offers critical lessons for modern political systems. Centralized control, ideological rigidity, and suppression of dissent are unsustainable in an era of globalization and information accessibility. Reforms must be carefully calibrated to avoid unintended consequences, and leaders must address economic and social grievances proactively. For instance, countries today can learn from the importance of balancing military spending with investments in public welfare. The Soviet Union's downfall serves as a cautionary tale: ignoring systemic issues and public discontent can lead to irreversible decline.

How Political Parties Serve Individual Citizens: Benefits and Representation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The political party of the Soviet Union was the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

Yes, the Soviet Union was a one-party state, with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) holding absolute power and controlling all aspects of governance.

Officially, no other political parties were allowed to operate in the Soviet Union. The CPSU maintained a monopoly on political power, and opposition parties were suppressed.