The Nativist political party, also known as the American Party or the Know-Nothing Party, emerged in the mid-19th century as a response to the growing influx of immigrants, particularly Irish Catholics, into the United States. Rooted in anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments, the party advocated for strict immigration laws, longer naturalization periods, and the preservation of Protestant values in American society. Members were sworn to secrecy, hence the moniker Know-Nothings, as they would claim to know nothing about the party when questioned. Despite its short-lived prominence in the 1850s, the Nativist movement reflected broader anxieties about cultural and economic changes in the United States during a period of rapid demographic transformation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A nativist political party advocates for the interests of native-born or long-established inhabitants over immigrants. |

| Historical Examples | Know Nothing Party (U.S., 1840s–1850s), National Front (France), UK Independence Party (UKIP). |

| Core Ideology | Prioritizes native citizens' rights, often at the expense of immigrants. |

| Immigration Stance | Opposes open immigration policies, supports strict immigration controls. |

| Cultural Focus | Promotes preservation of national culture, traditions, and identity. |

| Economic Policies | Often protectionist, favoring native workers over foreign labor. |

| Political Strategies | Uses populist rhetoric, appeals to national pride, and fear of outsiders. |

| Social Views | Tends to be conservative on social issues, resisting multiculturalism. |

| Global Presence | Exists in various forms across Europe, North America, and other regions. |

| Modern Examples | Alternative for Germany (AfD), Sweden Democrats, and similar parties. |

| Criticisms | Accused of xenophobia, racism, and promoting division. |

Explore related products

$9.99 $19.99

What You'll Learn

- Origins and Formation: Anti-immigrant sentiment led to the rise of the nativist political party in the 1800s

- Key Beliefs: Nativists prioritized native-born citizens, opposed immigration, and advocated for Protestant values

- Notable Parties: The Know-Nothing Party (American Party) was the most prominent nativist organization

- Political Impact: Nativist policies influenced immigration laws and fueled xenophobic rhetoric in American politics

- Decline and Legacy: The nativist movement faded by the 1860s but left a lasting impact on U.S. politics

Origins and Formation: Anti-immigrant sentiment led to the rise of the nativist political party in the 1800s

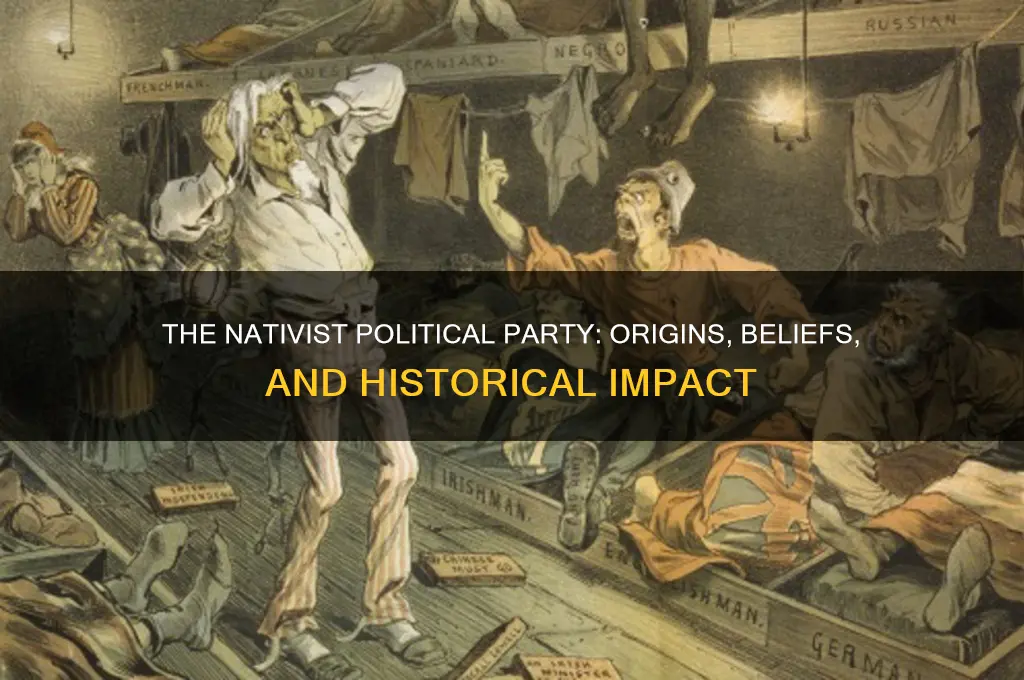

In the mid-19th century, the United States experienced a surge in immigration, particularly from Ireland and Germany, which fueled anxieties among native-born citizens. These newcomers, often Catholic and perceived as culturally distinct, competed for jobs and resources, exacerbating economic tensions. This environment of fear and competition laid the groundwork for the nativist movement, which sought to protect the interests of established citizens. The nativist political party, known as the Know-Nothing Party, emerged as a direct response to these anti-immigrant sentiments, advocating for policies that restricted immigration and prioritized the rights of native-born Americans.

The formation of the Know-Nothing Party was not merely a reaction to demographic changes but also a reflection of deeper societal insecurities. Nativists feared that immigrants, particularly Catholics, posed a threat to the nation’s Protestant values and political stability. They believed that these newcomers were loyal to foreign powers, such as the Pope, rather than the United States. This suspicion culminated in the party’s secretive nature—members were instructed to say they “knew nothing” about the organization when questioned, hence the name. This secrecy, however, did little to mask their openly anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic agenda.

To understand the party’s rise, consider the historical context: the 1840s and 1850s were marked by economic instability, including the Panic of 1857, which left many Americans jobless and desperate. Immigrants were often scapegoated for these hardships, making nativist rhetoric resonate with a broad audience. The Know-Nothing Party capitalized on this sentiment, proposing measures like extending the naturalization process from 5 to 21 years and restricting public office to native-born citizens. These policies were not just about exclusion; they were a call to preserve what nativists saw as the nation’s cultural and economic integrity.

Despite its short-lived prominence, the Know-Nothing Party’s impact was significant. It demonstrated how anti-immigrant sentiment could be weaponized for political gain, a tactic that has reappeared throughout American history. The party’s decline began when its focus on immigration failed to address the more pressing issue of slavery, which ultimately divided the nation. However, its legacy endures as a cautionary tale about the dangers of xenophobia and the fragility of unity in the face of demographic change.

In practical terms, the rise of the nativist political party serves as a reminder of the importance of addressing economic and cultural anxieties without resorting to exclusionary policies. Modern societies grappling with immigration must learn from this history, fostering dialogue and integration rather than fear and division. By understanding the origins of nativism, we can better navigate contemporary debates on immigration, ensuring that history does not repeat itself in harmful ways.

Why People Join Political Parties: Motivations and Influences Explored

You may want to see also

Key Beliefs: Nativists prioritized native-born citizens, opposed immigration, and advocated for Protestant values

Nativist political movements have historically hinged on a clear hierarchy of belonging, placing native-born citizens at the apex of societal value. This prioritization wasn’t merely symbolic; it translated into policies favoring those born within national borders for jobs, political representation, and social resources. For instance, the 19th-century Know-Nothing Party in the U.S. pushed for a 21-year residency requirement for citizenship, effectively sidelining recent immigrants from civic participation. This emphasis on nativity wasn’t just about numbers—it was about preserving a perceived cultural and economic monopoly for the "original" population.

Opposition to immigration within nativist ideologies wasn’t uniform; it often targeted specific groups deemed culturally or religiously incompatible. In the U.S., Irish and German Catholics in the mid-1800s, and later Southern and Eastern Europeans, faced the brunt of nativist hostility. The Immigration Act of 1924, influenced by nativist sentiments, established quotas favoring Northern and Western Europeans while drastically limiting arrivals from Asia and Africa. This selective opposition wasn’t just about population control—it was about maintaining a demographic status quo that nativists believed defined the nation’s identity.

Advocacy for Protestant values was a cornerstone of nativist ideology, particularly in the U.S. and parts of Europe. Nativists often equated Protestantism with patriotism, viewing it as the moral and cultural bedrock of society. For example, the American Protective Association in the late 19th century campaigned against Catholic influence in schools and government, fearing it would undermine Protestant ethics. This religious exclusivity extended to public life, with nativists pushing for policies like mandatory Bible readings in schools using the King James Version—a distinctly Protestant text.

The interplay of these beliefs—prioritizing native-born citizens, opposing immigration, and advocating for Protestant values—created a self-reinforcing ideology. By centering Protestantism, nativists justified excluding immigrants, particularly Catholics and Jews, who were portrayed as threats to the nation’s moral fabric. Simultaneously, favoring native-born citizens ensured that political and economic power remained within a tightly defined group. This trifecta of beliefs wasn’t just about exclusion; it was about constructing a homogeneous national identity, often at the expense of diversity and inclusivity.

Practical manifestations of these beliefs can be seen in historical policies and social movements. For instance, nativist-driven literacy tests for voting in the early 20th century disproportionately targeted immigrants, while the establishment of "Sunday laws" restricting commerce aimed to enforce Protestant Sabbath observance. Today, while overt religious advocacy has waned, the prioritization of native-born citizens and anti-immigration rhetoric persist in modern political discourse. Understanding these historical roots offers insight into contemporary debates on immigration, citizenship, and cultural identity, revealing how nativist beliefs continue to shape policy and public opinion.

Amy Coney Barrett's Political Affiliation: Unraveling Her Party Ties

You may want to see also

Notable Parties: The Know-Nothing Party (American Party) was the most prominent nativist organization

The Know-Nothing Party, formally known as the American Party, stands as the most prominent nativist organization in American political history. Emerging in the 1840s and peaking in the 1850s, this party capitalized on widespread anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment, particularly targeting Irish and German newcomers. Its members were sworn to secrecy about their activities, leading to the moniker "Know-Nothings" when questioned about their organization. This secretive nature, combined with their nativist agenda, made them a unique and influential force in mid-19th-century politics.

At its core, the Know-Nothing Party advocated for policies that restricted immigration, extended the naturalization process to 21 years, and barred Catholics from holding public office. These measures were framed as necessary to protect American values and institutions from what they perceived as foreign and religious threats. The party’s platform resonated strongly in urban areas experiencing rapid demographic changes due to immigration. For instance, in the 1854 elections, the Know-Nothings achieved significant victories, winning control of legislatures in several states and sending dozens of representatives to Congress. Their success demonstrated the depth of nativist sentiment in a nation grappling with cultural and economic shifts.

However, the Know-Nothing Party’s rise was as swift as its decline. Internal divisions over slavery, a contentious issue of the time, fractured the party’s unity. While some members prioritized nativism, others aligned with pro-slavery or anti-slavery factions, diluting their focus. The party’s inability to sustain a cohesive message, coupled with the outbreak of the Civil War, led to its rapid disintegration by the late 1850s. Despite its short-lived prominence, the Know-Nothings left a lasting legacy, illustrating how nativist fears can temporarily reshape the political landscape.

To understand the Know-Nothing Party’s impact, consider its role as a precursor to later nativist movements. Its tactics—such as secrecy, fear-mongering, and exclusionary policies—have reappeared in various forms throughout American history. For instance, the party’s emphasis on protecting native-born citizens from perceived outsiders echoes in modern debates about immigration and national identity. By studying the Know-Nothings, one gains insight into the cyclical nature of nativism and its enduring appeal in times of social and economic upheaval.

In practical terms, the Know-Nothing Party serves as a cautionary tale for contemporary politics. Its rise underscores the dangers of exploiting fear and division for political gain. While nativist sentiments may temporarily mobilize voters, they often lead to policies that alienate communities and undermine social cohesion. For those interested in political history or current affairs, examining the Know-Nothings offers valuable lessons on the consequences of exclusionary ideologies and the importance of inclusive governance.

Understanding France's Political Party System: Structure, Influence, and Dynamics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.91 $29.99

$21.49 $37

Political Impact: Nativist policies influenced immigration laws and fueled xenophobic rhetoric in American politics

Nativist policies have left an indelible mark on American immigration laws, shaping them in ways that often prioritized exclusion over inclusion. The Know-Nothing Party of the mid-19th century, a quintessential nativist movement, advocated for stringent restrictions on immigration, particularly targeting Irish and German Catholics. Their efforts led to the first significant legislative push for limiting immigration, setting a precedent for future policies. By framing immigrants as threats to American jobs, culture, and security, nativists successfully influenced the passage of laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred Chinese laborers from entering the country. This legislative shift demonstrated how nativist rhetoric could translate into concrete, discriminatory policies.

The political impact of nativism extends beyond legislation to the pervasive use of xenophobic rhetoric in American politics. Nativist movements have long exploited fears of the "other" to mobilize support, often portraying immigrants as invaders intent on undermining American values. This strategy was evident in the early 20th century with the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which targeted not only African Americans but also immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. By linking immigration to crime, economic hardship, and cultural decay, nativists fueled public anxiety, making it easier to justify harsh immigration policies. This rhetoric persists today, with modern politicians echoing similar sentiments to garner support for border walls and travel bans.

To understand the enduring influence of nativism, consider its role in shaping public opinion. Nativist policies often thrive during periods of economic uncertainty or social upheaval, when scapegoating immigrants becomes a convenient solution to complex problems. For instance, during the Great Depression, nativist sentiments contributed to the repatriation of Mexican immigrants, including many U.S. citizens of Mexican descent, under the guise of protecting American jobs. This historical example underscores how nativist policies can lead to inhumane outcomes, even when disguised as pragmatic solutions. By studying these patterns, we can better recognize and counter contemporary attempts to exploit xenophobia for political gain.

A practical takeaway from this analysis is the importance of critically examining political rhetoric surrounding immigration. Voters and policymakers alike must scrutinize claims that immigrants pose an existential threat to the nation, as such assertions often lack empirical evidence. Instead, focus on data-driven approaches that address the root causes of economic and social challenges. For instance, investing in education, infrastructure, and job creation can alleviate many of the issues nativists attribute to immigration. By adopting a more nuanced perspective, we can move beyond divisive policies and foster a more inclusive society that values diversity as a strength rather than a liability.

Amplify Your Voice: Best Platforms for Sharing Political Art

You may want to see also

Decline and Legacy: The nativist movement faded by the 1860s but left a lasting impact on U.S. politics

The nativist movement, embodied by the Know-Nothing Party in the 1850s, was a fiery response to rapid immigration and cultural change in the United States. Fueled by fears of Catholic influence and economic competition, it briefly captured national attention with its anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic platform. Yet, by the 1860s, the movement had all but vanished, overshadowed by the Civil War and its own internal contradictions. Despite its short-lived prominence, the nativist movement’s legacy persists, shaping American political discourse in ways both subtle and profound.

Consider the mechanics of its decline: the Know-Nothing Party fractured over the issue of slavery, a divide that mirrored the nation’s broader tensions. Leaders like Millard Fillmore, who ran as the party’s presidential candidate in 1856, failed to unite members on a cohesive agenda. Meanwhile, the outbreak of the Civil War shifted public focus away from immigration concerns, rendering nativist fears secondary to the existential crisis of the Union. This collapse wasn’t merely a failure of leadership or timing; it exposed the movement’s inability to adapt to a rapidly changing political landscape. Yet, its decline didn’t erase its influence—it merely transformed it.

The nativist movement’s legacy is most evident in its recurring themes within American politics. Anti-immigrant sentiment, once directed at Irish and German Catholics, has resurfaced in various forms, from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to contemporary debates over border security. The movement’s emphasis on "American identity" as a fixed, exclusionary concept laid the groundwork for later policies and rhetoric that sought to define who belongs and who doesn’t. For instance, the 1924 Immigration Act, which established quotas favoring Northern and Western Europeans, echoed nativist fears of "foreign" influence. This enduring legacy demonstrates how nativism’s core ideas, though dormant at times, remain embedded in the nation’s political DNA.

To understand nativism’s impact today, examine its role in shaping modern political strategies. The movement pioneered the use of fear-based messaging and identity politics, tactics still employed by politicians across the spectrum. For example, the Know-Nothings’ secret society structure, with its oaths and rituals, created a sense of exclusivity that resonated with voters. Similarly, contemporary campaigns often appeal to a narrowly defined "American" identity, leveraging anxieties about cultural or economic displacement. While the specifics have evolved, the underlying framework—us vs. them—remains a powerful tool in mobilizing support.

Finally, the nativist movement serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of exclusionary politics. Its decline wasn’t just a matter of external events; it was also a result of its own rigid ideology, which alienated potential allies and failed to address broader societal issues. Yet, its legacy reminds us that such movements, though fleeting, can leave deep imprints on a nation’s psyche. As the U.S. continues to grapple with questions of identity and belonging, the nativist movement’s rise and fall offer both a warning and a roadmap for understanding the enduring power of fear and division in politics.

Discovering Your Political Party in the USA: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Nativist political party, also known as the Know-Nothing Party, was a mid-19th-century American political movement formally called the American Party. It was characterized by its anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and nationalist sentiments, primarily targeting Irish and German immigrants.

The Nativist political party, or the American Party, was most prominent in the 1840s and 1850s. Its main goals included restricting immigration, extending the naturalization process to 21 years, and limiting the political influence of Catholics and immigrants, whom they viewed as threats to American values and Protestant dominance.

The Nativist political party declined in the late 1850s due to internal divisions, the rise of the Republican Party, and the growing focus on the slavery issue, which overshadowed nativist concerns. The party's inability to unite around a cohesive platform beyond anti-immigrant rhetoric also contributed to its downfall.