Joseph Stalin's political philosophy was deeply rooted in Marxism-Leninism, which he adapted to consolidate his power and shape the Soviet Union into a totalitarian state. While nominally adhering to the principles of communism, Stalin's ideology was characterized by his emphasis on rapid industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and the centralization of authority under his personal dictatorship. His policies, such as the Five-Year Plans and the Great Purge, were driven by a ruthless pragmatism aimed at modernizing the Soviet Union and eliminating perceived threats, both internal and external. Stalin's interpretation of socialism in one country prioritized national strength and self-sufficiency over international revolution, marking a significant departure from Lenin's earlier focus on global proletarian uprising. His legacy remains contentious, as his regime achieved significant economic and military advancements but at the cost of millions of lives and the suppression of individual freedoms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Marxism-Leninism | Stalin adhered to the principles of Marxism-Leninism, emphasizing class struggle, dictatorship of the proletariat, and the eventual transition to communism. |

| Socialism in One Country | Focused on building socialism within the Soviet Union rather than relying on global revolution, as advocated by Trotsky. |

| Centralized Control | Strong emphasis on centralized state control over all aspects of society, including economy, politics, and culture. |

| Collectivization | Forced collectivization of agriculture to eliminate private ownership and modernize rural areas, often with brutal consequences. |

| Five-Year Plans | Implemented rapid industrialization through Five-Year Plans to transform the Soviet Union into a major industrial power. |

| Cult of Personality | Cultivated a cult of personality, portraying himself as an infallible leader and the embodiment of the Soviet state. |

| Political Repression | Used widespread political repression, including purges, show trials, and the Gulag system, to eliminate perceived enemies. |

| Nationalism | Promoted Russian nationalism and a sense of Soviet patriotism, often at the expense of other ethnic groups within the USSR. |

| Anti-Imperialism | Opposed Western imperialism and sought to expand Soviet influence globally through proxy wars and support for communist movements. |

| Totalitarianism | Established a totalitarian regime with complete control over media, education, and dissent, suppressing individual freedoms. |

| Rapid Modernization | Prioritized rapid modernization and industrialization, often at the cost of human lives and living standards. |

| Ideological Orthodoxy | Enforced strict adherence to his interpretation of Marxism-Leninism, purging dissenters and deviants from the party. |

| Military Buildup | Strengthened the Soviet military to defend against perceived external threats and project power globally. |

| Cultural Control | Controlled cultural expression through socialist realism, ensuring art, literature, and media aligned with state ideology. |

| Economic Autarky | Pursued economic self-sufficiency to reduce dependence on capitalist nations and strengthen the Soviet economy. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Marxism-Leninism Foundation: Stalin's adherence to Marxist-Leninist principles as the core of his ideology

- Socialism in One Country: Focus on building socialism within the Soviet Union before global revolution

- Totalitarian Control: Centralized power, repression, and state control over all aspects of society

- Collectivization Policies: Forced agricultural collectivization to modernize and control rural economy

- Cult of Personality: Promotion of Stalin as an infallible leader to solidify authority

Marxism-Leninism Foundation: Stalin's adherence to Marxist-Leninist principles as the core of his ideology

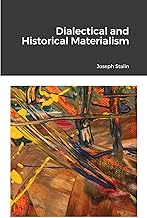

Joseph Stalin's political philosophy was deeply rooted in Marxism-Leninism, which he adhered to as the foundational core of his ideology. Marxism-Leninism, a synthesis of Marxist theory and Leninist practice, provided Stalin with a framework for understanding class struggle, the role of the proletariat, and the necessity of a vanguard party to lead the revolution. Stalin's commitment to these principles was unwavering, though his interpretation and application often diverged from the orthodoxy established by Marx and Lenin. At its core, Stalin's ideology emphasized the dictatorship of the proletariat, the centralization of power, and the rapid industrialization and collectivization of the Soviet Union as essential steps toward achieving socialism and, ultimately, communism.

Stalin's adherence to Marxist-Leninist principles is evident in his belief in the historical materialist perspective, which posits that economic and class relations are the driving forces of history. He viewed the Soviet Union as a proletarian state engaged in a global struggle against capitalism and imperialism. This perspective justified his policies of rapid industrialization, as he believed that a strong industrial base was necessary to defend the socialist state and lay the groundwork for communism. Stalin's Five-Year Plans, which prioritized heavy industry and centralized economic control, were direct applications of Marxist-Leninist principles, aiming to transform the Soviet Union into a modern industrial power capable of competing with capitalist nations.

Another key aspect of Stalin's Marxist-Leninist foundation was his emphasis on the vanguard role of the Communist Party. Following Lenin's teachings, Stalin argued that the Party was the embodiment of the proletariat's revolutionary consciousness and the only force capable of leading the masses toward socialism. Under Stalin, the Party became increasingly centralized and authoritarian, with him at its helm as the undisputed leader. This centralization was justified as a means to ensure unity and discipline in the face of internal and external threats, reflecting the Leninist principle of democratic centralism. However, Stalin's interpretation of this principle often led to the suppression of dissent and the consolidation of his personal power.

Stalin's interpretation of proletarian internationalism also remained firmly within the Marxist-Leninist framework. He saw the Soviet Union as the global bastion of socialism and sought to support revolutionary movements worldwide. The Comintern (Communist International), though initially established by Lenin, became a tool for Stalin to extend Soviet influence and promote his vision of socialism. While this aligned with Marxist-Leninist ideals of global revolution, Stalin's policies were often pragmatic, prioritizing Soviet interests over the broader goals of international socialism.

Finally, Stalin's concept of socialism in one country marked a significant, though controversial, adherence to Marxist-Leninist principles. Building on Lenin's ideas, Stalin argued that the Soviet Union could achieve socialism independently of a global revolution, given its vast resources and the strength of its proletarian state. This approach allowed Stalin to focus on internal development while still maintaining the ideological framework of Marxism-Leninism. Critics, however, argued that this policy contradicted the internationalist spirit of Marx and Lenin. Despite these debates, Stalin's commitment to Marxism-Leninism as the foundation of his ideology remained unshaken, shaping his policies and the trajectory of the Soviet Union.

In conclusion, Stalin's political philosophy was firmly grounded in Marxism-Leninism, which he interpreted and applied to suit the specific challenges of the Soviet Union. His adherence to principles such as historical materialism, the vanguard role of the Party, proletarian internationalism, and socialism in one country demonstrates the centrality of Marxist-Leninist ideology to his worldview. While his methods were often harsh and his interpretations controversial, Stalin's policies were consistently framed within the theoretical framework of Marxism-Leninism, making it the cornerstone of his ideological legacy.

How COVID-19 Polarized Politics: A Deep Dive into the Divide

You may want to see also

Socialism in One Country: Focus on building socialism within the Soviet Union before global revolution

Joseph Stalin's political philosophy was deeply rooted in Marxist-Leninist ideology, but he adapted it to the specific conditions of the Soviet Union, leading to the development of the concept of "Socialism in One Country." This theory, formulated in the late 1920s, marked a significant shift in Soviet strategy, prioritizing the consolidation of socialism within the USSR over the immediate pursuit of global revolution. Stalin argued that the Soviet Union could and should build a socialist society independently, even if the proletarian revolution had not yet succeeded in other countries. This approach was a pragmatic response to the challenges faced by the young Soviet state, including economic backwardness, international isolation, and the need to strengthen its internal structures.

The core idea behind "Socialism in One Country" was that the Soviet Union could achieve socialism by industrializing and modernizing its economy, collectivizing agriculture, and eliminating capitalist elements within its borders. Stalin believed that by focusing on internal development, the USSR could become a strong, self-sufficient socialist state capable of defending itself against external threats. This strategy was in contrast to Leon Trotsky's theory of "Permanent Revolution," which emphasized the necessity of continuous global revolution to sustain socialism in any single country. Stalin's approach was more inward-looking, aiming to create a stable socialist foundation within the Soviet Union before considering broader revolutionary goals.

Stalin's implementation of "Socialism in One Country" involved rapid industrialization and the Five-Year Plans, which aimed to transform the USSR from an agrarian economy into an industrial powerhouse. The First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932), for instance, focused on heavy industry, such as steel, coal, and machinery production, laying the groundwork for economic self-sufficiency. Collectivization of agriculture was another key component, as Stalin sought to eliminate the kulaks (wealthier peasants) and reorganize farming into state-controlled collectives. While these policies led to significant economic growth, they also resulted in immense human suffering, including famine, forced labor, and widespread repression.

Politically, "Socialism in One Country" reinforced Stalin's consolidation of power and the centralization of authority. The focus on internal development allowed Stalin to justify his authoritarian rule as necessary for achieving socialist goals. The Communist Party, under Stalin's leadership, became the sole arbiter of progress, and dissent was ruthlessly suppressed. This period also saw the cult of personality surrounding Stalin grow, as he was portrayed as the indispensable leader guiding the Soviet Union toward socialism. The ideology of "Socialism in One Country" thus became intertwined with Stalin's personal dictatorship, shaping the political and social landscape of the USSR for decades.

Internationally, Stalin's policy had significant implications. While the Soviet Union continued to support communist movements abroad, the emphasis on internal development meant that global revolution took a backseat. The Comintern (Communist International) shifted its focus to defending the USSR and promoting its interests rather than actively fomenting revolution in other countries. This pragmatic approach allowed the Soviet Union to navigate complex international relations, particularly during the rise of fascism in Europe, but it also alienated some leftist groups who saw Stalin's policies as a betrayal of revolutionary ideals.

In conclusion, "Socialism in One Country" was a defining aspect of Stalin's political philosophy, reflecting his focus on building a strong, self-reliant socialist state within the Soviet Union. This strategy shaped the USSR's economic, political, and social development during Stalin's rule, leaving a lasting impact on its history. While it achieved rapid industrialization and modernization, it also came at a tremendous human cost and solidified Stalin's authoritarian regime. The theory remains a controversial and pivotal element in understanding Stalinism and its legacy.

Australian Ballot: Does It Favor One Political Party Over Others?

You may want to see also

Totalitarian Control: Centralized power, repression, and state control over all aspects of society

Joseph Stalin's political philosophy was deeply rooted in the principles of totalitarianism, characterized by centralized power, widespread repression, and pervasive state control over all aspects of society. Under Stalin's leadership, the Soviet Union became a quintessential example of a totalitarian regime, where the state's authority was absolute and all dissenting voices were systematically silenced. Stalin's ideology, often referred to as Stalinism, was a rigid and authoritarian interpretation of Marxism-Leninism, emphasizing the necessity of a strong, centralized state to achieve socialist goals.

Centralized power was the cornerstone of Stalin's totalitarian control. He consolidated authority in his own hands, eliminating any potential rivals within the Communist Party and the government. The Politburo, the highest policy-making body, became a mere rubber stamp for Stalin's decisions. The state apparatus was reorganized to ensure that all institutions, from the military to the judiciary, were under his direct command. This concentration of power allowed Stalin to dictate policies without opposition, fostering a cult of personality that portrayed him as the infallible leader of the proletariat.

Repression was a key tool in maintaining Stalin's totalitarian regime. The secret police, first the OGPU and later the NKVD, were instrumental in enforcing loyalty and suppressing dissent. Mass surveillance, arbitrary arrests, and show trials became commonplace. The Great Purge of the 1930s exemplifies this repression, as millions of people, including party members, military officers, and ordinary citizens, were executed, imprisoned, or sent to forced labor camps (Gulags) on trumped-up charges of treason or counter-revolutionary activities. This reign of terror instilled fear and ensured compliance, as no one was beyond the reach of the state's punitive measures.

State control over all aspects of society was another hallmark of Stalin's totalitarianism. The economy was fully nationalized and centralized through a series of Five-Year Plans, which prioritized rapid industrialization and collectivization of agriculture. Private enterprise was virtually eradicated, and all economic activities were directed by the state. Cultural and intellectual life was also tightly controlled, with the promotion of socialist realism as the only acceptable artistic and literary form. Education, media, and propaganda were used to indoctrinate the population with the regime's ideology, suppressing any alternative viewpoints. Even personal freedoms were curtailed, as the state dictated where people could live, work, and travel.

The totalitarian control exerted by Stalin's regime extended to the family and individual life. Collectivization destroyed traditional rural communities, uprooting millions of peasants and forcing them into collective farms. The state also sought to redefine family structures, promoting communal living and discouraging religious practices. Surveillance and informants were pervasive, creating an atmosphere of mistrust even within families. This all-encompassing control aimed to mold Soviet citizens into obedient subjects of the state, devoid of independent thought or dissent.

In conclusion, Stalin's political philosophy was defined by totalitarian control, manifested through centralized power, relentless repression, and state domination over every facet of society. His regime employed fear, propaganda, and coercion to maintain absolute authority, transforming the Soviet Union into a society where individual freedoms were subjugated to the state's ideological and political objectives. The legacy of Stalinism serves as a stark reminder of the dangers inherent in unchecked power and the suppression of human rights.

Dan McCready's Political Party Affiliation: Unraveling His Political Identity

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Collectivization Policies: Forced agricultural collectivization to modernize and control rural economy

Joseph Stalin's political philosophy was deeply rooted in Marxism-Leninism, emphasizing rapid industrialization, centralized control, and the transformation of the Soviet Union into a socialist state. A cornerstone of his policies was forced agricultural collectivization, a radical measure aimed at modernizing the rural economy and consolidating state control over agriculture. This policy, implemented in the late 1920s and early 1930s, sought to replace the traditional peasant-based farming system with large, state-controlled collective farms known as *kolkhozes* and *sovkhozes*. Stalin viewed collectivization as essential for achieving socialism, ensuring food security for urban industrialization, and eliminating the kulaks, the wealthier peasants whom he considered a threat to socialist ideals.

The collectivization process was brutal and coercive, characterized by the forced confiscation of land, livestock, and agricultural tools from peasants. Peasants were compelled to join collective farms under the threat of violence, deportation, or execution. The state set unrealistic grain procurement quotas, which often left peasants with insufficient food for themselves. Resistance to collectivization was widespread, particularly among the kulaks, who were labeled "class enemies" and subjected to brutal repression. Millions of kulaks were deported to remote regions of the Soviet Union, where they faced harsh living conditions and high mortality rates. This campaign of dekulakization was not only a means of eliminating opposition but also a way to redistribute resources and labor to the collective farms.

Stalin's collectivization policies had profound economic and social consequences. While the goal was to modernize agriculture and increase productivity, the immediate results were disastrous. The forced relocation and resistance of peasants led to a significant decline in agricultural output, contributing to widespread famine, particularly in Ukraine (the Holodomor), Kazakhstan, and parts of Russia. The famine of 1932–1933 alone resulted in millions of deaths, highlighting the human cost of Stalin's policies. Despite these setbacks, collectivization did achieve its political objective of bringing the rural economy under state control, eliminating the peasant class as an independent force, and redirecting agricultural surplus to support industrialization.

From a political perspective, collectivization was a tool for strengthening the Soviet state's authority over rural areas. By dismantling the traditional peasant economy, Stalin aimed to create a more obedient and dependent rural population. Collective farms were integrated into the state's centralized planning system, allowing the government to dictate crop production, distribution, and procurement. This control was crucial for financing industrialization, as the state could extract resources from the countryside to fuel urban development. Collectivization also served ideological purposes, as it was presented as a necessary step toward building a classless, socialist society.

In conclusion, Stalin's collectivization policies were a central component of his political philosophy, reflecting his commitment to rapid modernization, state control, and the eradication of perceived class enemies. While the policies achieved their goal of centralizing the rural economy, they came at an immense human cost and caused long-term damage to Soviet agriculture. Collectivization remains a stark example of the tension between ideological ambition and practical consequences in Stalin's rule, illustrating the extreme measures he was willing to take to transform Soviet society according to his vision of socialism.

Understanding SNP's Role and Impact in British Politics Explained

You may want to see also

Cult of Personality: Promotion of Stalin as an infallible leader to solidify authority

Joseph Stalin's political philosophy was deeply intertwined with the consolidation of power and the creation of a totalitarian state. Central to this was the Cult of Personality, a systematic campaign to promote Stalin as an infallible, almost divine leader. This cult was not merely a propaganda tool but a cornerstone of his regime, designed to solidify his authority and ensure unquestioning loyalty from the Soviet populace. By deifying Stalin, the regime aimed to eliminate dissent, foster unity, and legitimize his policies, no matter how brutal or misguided.

The Cult of Personality was meticulously constructed through state-controlled media, art, and education. Stalin's image was omnipresent, appearing in newspapers, posters, and public monuments. He was portrayed as the "Father of Nations," a benevolent leader who single-handedly guided the Soviet Union toward prosperity and strength. His role in the Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent industrialization of the USSR was exaggerated, while his mistakes and atrocities were erased from public discourse. This constant reinforcement of his greatness created an aura of invincibility, making it nearly impossible for citizens to question his decisions without feeling unpatriotic or disloyal.

Stalin's infallibility was further cemented through the rewriting of history and the suppression of dissenting narratives. Historians and writers were compelled to glorify his contributions, while any mention of his rivals, such as Leon Trotsky, was purged from textbooks and archives. The cult extended to personal adoration, with songs, poems, and even religious-like rituals dedicated to him. Schools and youth organizations indoctrinated children from a young age, teaching them to revere Stalin as a hero and a savior. This pervasive worship was not just encouraged but enforced, with severe consequences for those who failed to participate.

The Cult of Personality also served to justify Stalin's authoritarian rule and the harsh policies of his regime. By presenting himself as the embodiment of the Soviet Union's ideals, Stalin could claim that any opposition to his leadership was tantamount to treason. This allowed him to carry out mass purges, forced collectivization, and other brutal measures under the guise of protecting the nation and its revolutionary spirit. The cult effectively merged Stalin's personal authority with the legitimacy of the Communist Party, making him the ultimate arbiter of truth and morality in Soviet society.

In essence, the Cult of Personality was a masterstroke in political manipulation, transforming Stalin from a politician into a symbol of the Soviet Union itself. By promoting him as infallible, the regime not only solidified his authority but also created a psychological barrier against dissent. This cult was a key element of Stalin's political philosophy, reflecting his belief in the necessity of absolute power and the use of propaganda to maintain control. Its legacy remains a stark reminder of how personality-driven leadership can distort ideology and subjugate an entire nation.

Understanding Value Politics: Core Principles, Impact, and Modern Relevance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Stalin's political philosophy was rooted in Marxism-Leninism, emphasizing the dictatorship of the proletariat, rapid industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and the centralization of power under the Communist Party. He also promoted the idea of "Socialism in One Country," focusing on building a socialist state in the Soviet Union rather than global revolution.

While both Stalin and Lenin adhered to Marxism-Leninism, Stalin's approach was more authoritarian and focused on rapid industrialization and collectivization, often using brutal methods to achieve his goals. Lenin, on the other hand, emphasized flexibility (e.g., the New Economic Policy) and prioritized the survival of the revolutionary state. Stalin's policies also shifted away from Lenin's vision of a global revolution to a more nationalist focus on the Soviet Union.

Terror was a central tool in Stalin's political philosophy, used to eliminate perceived enemies, consolidate power, and enforce ideological conformity. The Great Purge of the 1930s, for example, targeted millions of people, including party members, military leaders, and ordinary citizens. Stalin justified this as necessary to protect the socialist state and ensure the purity of the revolution, viewing terror as a means to achieve his vision of a communist society.