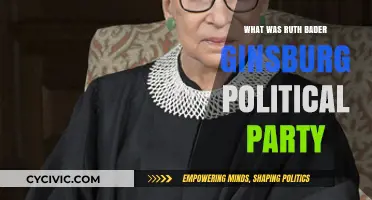

Pol Pot's political party was the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), also known as the Khmer Rouge, which rose to power in Cambodia in 1975 following a brutal civil war. Under Pol Pot's leadership, the Khmer Rouge implemented a radical agrarian socialist regime, aiming to create a classless society by forcibly relocating urban populations to rural areas and abolishing private property, religion, and education. This extreme ideology led to the Cambodian Genocide, during which an estimated 1.5 to 3 million people perished due to executions, forced labor, starvation, and disease. The regime's oppressive policies and widespread atrocities ended in 1979 when Vietnam invaded Cambodia and ousted the Khmer Rouge from power.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), also known as the Khmer Rouge |

| Ideology | Maoism, Agrarian socialism, Ultranationalism, Totalitarianism |

| Leader | Pol Pot (Saloth Sar) |

| Founding Date | 1951 (as the Kampuchean People's Revolutionary Party), later renamed CPK |

| Dissolution | 1997 (officially disbanded after Pol Pot's death) |

| Political Goals | Establishment of a classless, agrarian socialist society |

| Methods | Mass killings, forced labor, re-education, and elimination of intellectuals |

| Rule Period | 1975–1979 (Democratic Kampuchea regime) |

| Key Policies | Year Zero policy, abolition of religion, currency, and private property |

| Human Rights Record | Genocide (Killing Fields), estimated 1.5 to 3 million deaths |

| International Relations | Supported by China, opposed by Vietnam and the West |

| Legacy | Widely condemned for crimes against humanity and genocide |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Khmer Rouge Origins: Founded in 1951 as the Communist Party of Kampuchea, later renamed Khmer Rouge

- Ideology: Marxist-Leninist with extreme agrarian socialism, aiming to create a classless society

- Leadership: Pol Pot became leader in 1963, consolidating power through purges and terror

- Year Zero Policy: 1975: Society reset, cities evacuated, and mass killings began

- Fall and Legacy: Regime collapsed in 1979; trials for genocide followed decades later

Khmer Rouge Origins: Founded in 1951 as the Communist Party of Kampuchea, later renamed Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge, a name that evokes images of extreme brutality and a nation scarred by genocide, emerged from a political party with a seemingly innocuous beginning. Founded in 1951 as the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), it was initially a small, clandestine group operating in the shadows of Cambodia's political landscape. This early incarnation was a far cry from the ruthless regime it would become, but its origins reveal the seeds of an ideology that would later justify unimaginable atrocities.

The CPK's formation was a response to the post-World War II political climate in Cambodia, then a French colony. Inspired by Marxist-Leninist principles and the success of communist revolutions in China and Vietnam, a group of Cambodian intellectuals and students sought to establish a similar movement. Among them was Saloth Sar, who would later adopt the nom de guerre Pol Pot. These early members were idealistic, driven by a desire to liberate Cambodia from colonial rule and establish a classless, agrarian society. Their initial activities were limited to clandestine meetings, propaganda distribution, and recruiting like-minded individuals, primarily from the country's small urban intelligentsia.

The party's transformation into the Khmer Rouge was gradual, marked by a series of ideological shifts and power struggles. In the 1960s, as the Vietnam War spilled over into Cambodia, the CPK began to radicalize. Pol Pot and his allies, who had received training in China, embraced a more extreme form of communism, emphasizing self-reliance, agrarian socialism, and a deep-seated nationalism. They renamed themselves the Khmer Rouge, a term that reflected their commitment to a purely Khmer (Cambodian) identity and their willingness to use violence to achieve their goals. This period saw the party's shift from a small, urban-based movement to a rural insurgency, as they established bases in the jungles and began to attract support from the peasant population.

The Khmer Rouge's rise to power was swift and brutal. By 1975, they had overthrown the US-backed Lon Nol government and established Democratic Kampuchea, a regime that would rule Cambodia with unparalleled savagery. Pol Pot's vision of a classless society was realized through forced labor, mass executions, and the systematic destruction of education, religion, and family structures. The party's origins as a small communist group in 1951 seem almost inconsequential when compared to the scale of the horrors they perpetrated. Yet, understanding this history is crucial. It highlights how extreme ideologies, when combined with charismatic leadership and a volatile political environment, can lead to catastrophic outcomes. The Khmer Rouge's origins serve as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked extremism and the importance of vigilance in safeguarding democratic values.

England's Anti-Slavery Political Party: Uncovering the Historical Stance

You may want to see also

Ideology: Marxist-Leninist with extreme agrarian socialism, aiming to create a classless society

Pol Pot's political party, the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), was driven by an ideology that fused Marxist-Leninist principles with extreme agrarian socialism, aiming to create a classless society. This ideology was not merely theoretical; it was implemented with ruthless precision during the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979. At its core, the CPK sought to dismantle all existing social structures and rebuild society from the ground up, prioritizing rural, agrarian labor as the foundation of a new, egalitarian order.

To understand this ideology, consider its dual roots. Marxist-Leninism provided the framework for a revolutionary overthrow of the bourgeoisie and the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat. However, the CPK’s interpretation was uniquely radical. They rejected urban industrialization, viewing cities as corrupt and exploitative. Instead, they embraced agrarian socialism, glorifying peasant farmers as the true proletariat. This shift was not just economic but cultural, as the regime sought to erase all remnants of modern society, including education, religion, and even family structures, to achieve their vision of a classless utopia.

The implementation of this ideology was brutal and methodical. Cities were evacuated, and millions were forcibly relocated to rural labor camps. The regime abolished money, private property, and markets, replacing them with collective farming and state-controlled distribution. Anyone deemed part of the old elite—intellectuals, professionals, or even those who wore glasses—was targeted for execution. The goal was purity: a society stripped of class distinctions, where everyone was a peasant-worker. However, this extreme approach led to widespread famine, disease, and genocide, with an estimated 1.5 to 2 million deaths.

Comparatively, while other Marxist-Leninist regimes prioritized industrialization, the CPK’s focus on agrarian socialism was unprecedented. This deviation from orthodoxy was both ideological and practical. Cambodia’s largely rural population made agrarian socialism seem feasible, but the regime’s refusal to adapt to reality—such as ignoring crop failures and refusing foreign aid—exacerbated the suffering. The CPK’s ideology was not just about equality; it was about purification through suffering, a dangerous belief that justified unimaginable cruelty.

In practice, the CPK’s vision of a classless society was unattainable. Instead of equality, they created a new hierarchy, with party cadres wielding absolute power over the masses. The regime’s extreme measures alienated the very people it claimed to liberate, leading to widespread resistance and ultimately its downfall. The legacy of this ideology is a cautionary tale: the pursuit of utopia, when taken to extremes, can lead to dystopia. For those studying political ideologies, the CPK serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked radicalism and the importance of balancing idealism with pragmatism.

Is the Supreme Court Affiliated with Any Political Party?

You may want to see also

Leadership: Pol Pot became leader in 1963, consolidating power through purges and terror

Pol Pot's rise to leadership in 1963 marked the beginning of a brutal and calculated consolidation of power within the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), later known as the Khmer Rouge. His ascent was not merely a political transition but a strategic takeover, characterized by a series of meticulously orchestrated purges and a reign of terror that silenced dissent and solidified his authority. This period underscores a chilling truth: leadership, when wielded without moral restraint, can become a tool for systemic destruction.

To understand Pol Pot's methods, consider the mechanics of his power grab. He exploited ideological purity as a pretext, systematically eliminating rivals within the party and anyone perceived as a threat—intellectuals, ethnic minorities, and even fellow cadres. The purges were not random but followed a precise logic: by removing potential challengers, he created a vacuum of power that only he could fill. This approach was both ruthless and effective, turning the CPK into a monolithic entity loyal solely to him. For those studying leadership dynamics, this serves as a cautionary tale: unchecked authority, combined with a culture of fear, can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

The terror Pol Pot employed was not just physical but psychological, designed to break the will of the populace. His regime weaponized paranoia, using propaganda and surveillance to ensure compliance. For instance, the Khmer Rouge’s slogan, "To keep you is no benefit; to destroy you is no loss," encapsulated their dehumanizing ideology. This method of control is a stark reminder of how leadership can distort societal norms, turning communities into instruments of their own oppression. Practical insight: in analyzing leadership, always examine the mechanisms of control and their impact on collective psychology.

Comparatively, Pol Pot’s leadership style contrasts sharply with democratic models, where power is distributed and accountability is built into the system. His regime thrived on centralization and secrecy, eliminating transparency and dissent. This comparison highlights the importance of institutional checks and balances in preventing authoritarian abuses. For leaders or aspiring leaders, the takeaway is clear: power must be balanced with accountability to avoid its misuse.

Finally, the legacy of Pol Pot’s leadership serves as a grim case study in the dangers of extreme ideology coupled with unchecked authority. His reign resulted in the deaths of approximately 1.5 to 2 million Cambodians through executions, forced labor, and starvation. This historical example is not just a reminder of the past but a warning for the present: leadership, when divorced from ethical considerations, can lead to unimaginable suffering. To avoid such outcomes, leaders must prioritize empathy, inclusivity, and the well-being of those they govern.

How Political Parties Shape Presidential Power and Policy Decisions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.14 $18.95

Year Zero Policy: 1975: Society reset, cities evacuated, and mass killings began

Pol Pot's Year Zero Policy, implemented in 1975, was a radical attempt to reshape Cambodian society by erasing its past and rebuilding it from scratch. This policy, driven by the Khmer Rouge’s extremist interpretation of Maoist and Marxist ideologies, sought to create an agrarian utopia by dismantling urban centers, abolishing currency, and eliminating class distinctions. The immediate evacuation of cities, forced labor in rural cooperatives, and the prohibition of religion, education, and family structures were its core tenets. However, this vision of a classless society was enforced through brutal means, including mass executions, starvation, and forced marches, resulting in the deaths of approximately 1.7 million Cambodians.

To understand the Year Zero Policy, consider it as a societal reset button—a violent erasure of history and culture. Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, was emptied within days, with its 2 million residents forcibly relocated to rural areas. Urban professionals, intellectuals, and anyone deemed a threat to the regime were targeted for extermination. The Khmer Rouge’s slogan, “To keep you is no benefit; to destroy you is no loss,” encapsulated their ruthless approach. This policy was not merely about relocation but about annihilating perceived enemies of the revolution, often through arbitrary killings at sites like the Killing Fields.

The implementation of Year Zero was marked by a chilling efficiency. Families were separated, children were indoctrinated into the regime, and traditional social structures were dismantled. The Khmer Rouge’s obsession with purity led to the persecution of ethnic minorities, religious groups, and anyone with ties to the previous government. Even wearing glasses or speaking a foreign language could result in execution, as these were seen as signs of intellectualism or foreign influence. This extreme social engineering aimed to create a homogeneous, obedient population, but it instead fostered widespread suffering and resistance.

A comparative analysis reveals the Year Zero Policy’s divergence from other revolutionary movements. While Mao’s Cultural Revolution and Stalin’s collectivization campaigns were similarly destructive, they retained some semblance of state infrastructure. Pol Pot’s regime, however, sought to obliterate all existing systems, including hospitals, schools, and religious institutions. This total rejection of modernity, coupled with the regime’s paranoia, made the Khmer Rouge’s rule uniquely devastating. Unlike other communist regimes, which often prioritized industrialization, Pol Pot’s focus on agrarian self-sufficiency led to economic collapse and widespread famine.

In practical terms, surviving the Year Zero Policy required conformity, resilience, and often sheer luck. Those who concealed their education or urban backgrounds had a slim chance of survival. Others joined the regime’s ranks, participating in its atrocities to protect themselves. For historians and educators, studying this period offers a stark reminder of the dangers of extremist ideologies and the fragility of human rights. It underscores the importance of preserving historical memory, as the Khmer Rouge attempted to erase Cambodia’s past entirely. The Year Zero Policy remains a cautionary tale about the catastrophic consequences of attempting to rebuild society through violence and coercion.

Pol Pot's Political Affiliation: Uncovering the Party He Joined

You may want to see also

Fall and Legacy: Regime collapsed in 1979; trials for genocide followed decades later

The Khmer Rouge regime, led by Pol Pot and his Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), met its demise in 1979, marking the end of a brutal four-year rule that left Cambodia scarred. This collapse was not merely a political event but a liberation for a nation held hostage by extreme ideology. Vietnamese forces, alongside Cambodian rebels, invaded and overthrew the regime, forcing Pol Pot and his followers into the jungles. The fall was swift, but the aftermath was a protracted struggle to rebuild a shattered society and seek justice for unimaginable atrocities.

Decades passed before the international community and Cambodia itself could confront the genocide head-on. The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), established in the 2000s, became the stage for long-delayed trials. These proceedings aimed to hold surviving Khmer Rouge leaders accountable for crimes against humanity, including mass murder, forced labor, and ethnic cleansing. The trials were not without controversy, plagued by political interference, funding issues, and the advanced age of the accused, which raised questions about the timing and efficacy of justice.

Analyzing the legacy of Pol Pot’s regime reveals a paradox: while the CPK sought to create a utopian agrarian society, it instead engineered a dystopia of suffering. The trials, though belated, served as a symbolic reckoning, offering survivors a measure of closure and a historical record of the regime’s crimes. However, they also highlighted the challenges of prosecuting genocide decades after the fact, particularly in a nation still grappling with trauma and political instability.

Practical lessons from this chapter of history emphasize the importance of timely intervention and robust international legal frameworks. For nations emerging from conflict, establishing truth commissions or hybrid courts early can prevent impunity and foster reconciliation. Additionally, preserving historical documentation and survivor testimonies is critical for future accountability efforts. Cambodia’s experience underscores that justice, though delayed, can still serve as a deterrent and a means of healing.

Instructively, the fall of Pol Pot’s regime and the subsequent trials offer a blueprint for addressing mass atrocities. First, prioritize the collection of evidence during and immediately after conflicts. Second, engage local communities in transitional justice processes to ensure their needs are met. Third, advocate for sustained international support to overcome political and logistical hurdles. These steps, while not foolproof, can help societies move from devastation to recovery with greater integrity and purpose.

Understanding the Primary Role of Political Parties in Democracy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Pol Pot's political party was called the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), also known as the Khmer Rouge.

The Communist Party of Kampuchea was officially established in 1951, though it gained prominence in the 1960s and 1970s.

The CPK adhered to a radical form of agrarian communism, influenced by Marxism-Leninism and Maoist principles, aiming to create a classless, rural society.

The Khmer Rouge seized power in April 1975 after a prolonged civil war against the U.S.-backed Lon Nol government, establishing Democratic Kampuchea.

The Khmer Rouge regime (1975–1979) led to the Cambodian Genocide, resulting in the deaths of approximately 1.5 to 3 million people through executions, forced labor, and starvation.