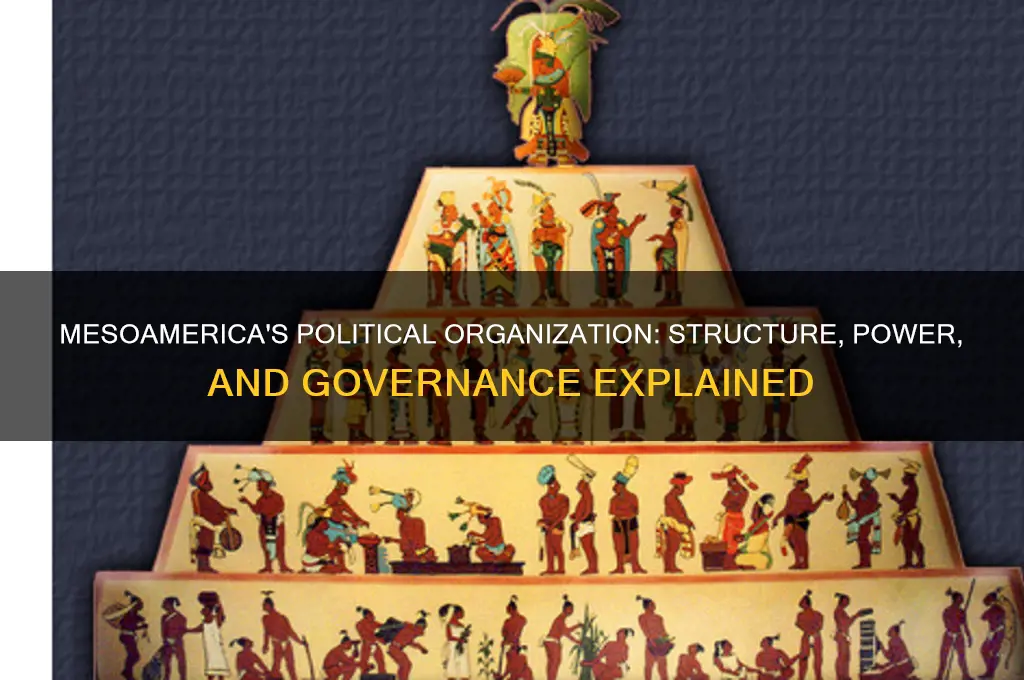

Mesoamerica, a cultural region encompassing parts of modern-day Mexico and Central America, was characterized by a complex and diverse political organization that evolved over millennia. From the early Olmec civilization to the mighty Aztec Empire, Mesoamerican societies developed sophisticated systems of governance, often centered around city-states, kingdoms, or empires. These political entities were typically ruled by divine kings or emperors, who claimed authority through their perceived connection to the gods. The region’s political structures were deeply intertwined with religion, social hierarchy, and economic systems, with rulers overseeing tribute collection, warfare, and monumental architecture. Alliances, rivalries, and conquests shaped the political landscape, as seen in the rise and fall of powers like Teotihuacan, the Maya city-states, and the Triple Alliance of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. Understanding Mesoamerica’s political organization offers insights into the ingenuity and complexity of pre-Columbian societies in the Americas.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Structure | Mesoamerica was organized into city-states or small kingdoms, often ruled by a divine king or ruler (tlatoani). |

| Centralized Authority | Power was centralized in the hands of an elite class, including priests, nobles, and military leaders. |

| Divine Kingship | Rulers were often considered divine or semi-divine, legitimizing their authority through religious ties. |

| Tribute Systems | Conquered territories paid tribute in goods, labor, or resources to the ruling city-state. |

| Military Expansion | Political power was often expanded through warfare and conquest of neighboring regions. |

| Administrative Bureaucracy | Complex administrative systems managed resources, taxation, and public works projects. |

| Religious Integration | Religion and politics were deeply intertwined, with rulers often serving as intermediaries between gods and people. |

| Urban Centers | Political power was concentrated in large urban centers like Tenochtitlan, Teotihuacan, and Monte Albán. |

| Alliances and Rivalries | City-states formed alliances or engaged in rivalries, leading to shifting political landscapes. |

| Social Hierarchy | Society was stratified, with rulers, nobles, priests, commoners, and slaves forming distinct classes. |

| Symbolism and Rituals | Political power was reinforced through elaborate rituals, monuments, and symbolic displays of authority. |

| Trade Networks | Political entities controlled trade routes and resources, enhancing their economic and political influence. |

| Succession Practices | Leadership often passed through hereditary lines, though merit and military success could also play a role. |

| Decentralized Regions | Some areas, like the Maya, had more decentralized political systems with multiple city-states coexisting. |

| Foreign Influence | Later periods saw external influences, such as the Aztec Empire's dominance over smaller polities. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- City-States and Kingdoms: Independent polities with distinct rulers, often competing for resources and influence

- Theocratic Leadership: Priests or divine rulers held political power, merging religion and governance

- Tribute Systems: Conquered regions paid resources to dominant empires like the Aztecs or Maya

- Military Conquest: Expansion through warfare to control territories and secure wealth and labor

- Administrative Divisions: Hierarchical structures with local governors overseeing provinces for centralized empires

City-States and Kingdoms: Independent polities with distinct rulers, often competing for resources and influence

Mesoamerica, a region encompassing modern-day Mexico and parts of Central America, was characterized by a diverse array of political organizations, with city-states and kingdoms being among the most prominent. These independent polities were governed by distinct rulers who wielded significant authority over their territories. Each city-state or kingdom functioned as a self-contained political entity, often with its own capital city, religious centers, and administrative systems. Examples include the city-states of Teotihuacan, Monte Albán, and Tikal, each of which flourished as a center of power during different periods in Mesoamerican history. These polities were not unified under a single empire but instead operated as autonomous units, each with its own identity and interests.

The rulers of these city-states and kingdoms, often referred to as kings or lords, held both political and religious authority. They were seen as intermediaries between the divine and the mortal world, which legitimized their rule. These leaders were responsible for maintaining order, overseeing religious ceremonies, and managing the economy, which was often based on agriculture, trade, and tribute systems. Their power was frequently reinforced through monumental architecture, such as pyramids and palaces, which served as symbols of their authority and the prosperity of their polities. The ability to mobilize labor for such projects was a key indicator of a ruler's strength and influence.

Competition among city-states and kingdoms was a defining feature of Mesoamerican politics. Resources such as fertile land, water, and trade routes were limited, leading to frequent conflicts and alliances. Warfare was common, with polities vying for dominance and control over neighboring territories. Victories in battle often resulted in the imposition of tribute systems, where the defeated polity was forced to provide goods, labor, or captives to the victor. This dynamic created a complex web of relationships, with some polities rising to regional prominence while others fell into decline. For instance, the expansion of the Aztec Empire in the late post-classic period was built on the conquest and subjugation of numerous city-states in the Valley of Mexico.

Despite their independence, city-states and kingdoms often engaged in diplomatic interactions, including marriage alliances, trade agreements, and religious exchanges. These interactions helped mitigate conflict and foster stability in certain regions. However, the absence of a centralized authority meant that Mesoamerica remained politically fragmented, with no single polity achieving long-term hegemony over the entire region. This fragmentation allowed for cultural and political diversity to flourish, as each city-state or kingdom developed its own unique traditions, languages, and systems of governance.

The decline of these independent polities often came through external conquest, internal strife, or environmental factors. For example, the collapse of Teotihuacan around 600 CE led to a power vacuum that allowed smaller city-states to emerge and compete for influence. Similarly, the Spanish conquest in the 16th century marked the end of indigenous political systems, as colonial rule replaced the autonomous city-states and kingdoms that had defined Mesoamerica for centuries. Understanding these polities provides insight into the complexity and dynamism of Mesoamerican political organization, highlighting the interplay between independence, competition, and cooperation in shaping the region's history.

Changing Political Party Affiliation: How, When, and Why It's Possible

You may want to see also

Theocratic Leadership: Priests or divine rulers held political power, merging religion and governance

In Mesoamerica, theocratic leadership was a defining feature of political organization, particularly in civilizations such as the Olmec, Maya, Aztec, and Zapotec. Under this system, priests or rulers who claimed divine authority held significant political power, effectively merging religious and governmental functions. These leaders were often seen as intermediaries between the divine and the mortal world, which legitimized their rule and centralized authority. Theocratic leadership ensured that religious rituals, cosmology, and moral codes were deeply intertwined with the administration of the state, creating a unified system of control.

Priests and divine rulers in Mesoamerica were not merely spiritual figures but also key decision-makers in matters of state. They oversaw the construction of monumental architecture, such as temples and pyramids, which served both religious and political purposes. These structures symbolized the ruler's divine connection and reinforced their authority. Additionally, priests were responsible for maintaining the ritual calendar, which dictated agricultural cycles, ceremonies, and sacrifices. By controlling these aspects, theocratic leaders ensured societal stability and the continued favor of the gods, which was believed to be essential for the prosperity of the community.

The divine status of rulers was often reinforced through elaborate rituals, iconography, and mythology. For example, Aztec emperors were considered living embodiments of the god Huitzilopochtli, while Maya kings claimed descent from celestial deities. This divine lineage granted them the right to rule and exempted them from the same laws as their subjects. Public ceremonies, such as coronations, sacrifices, and processions, further solidified their sacred authority and demonstrated their role as protectors of cosmic order.

Governance under theocratic leadership was also characterized by a hierarchical structure that mirrored religious beliefs. Below the divine ruler were nobles and priests who administered regions, collected tribute, and enforced laws. These officials were often selected based on their lineage or religious knowledge, ensuring loyalty to the central authority. The integration of religion into governance meant that dissent was not only a political act but also a religious transgression, which discouraged opposition and maintained social cohesion.

Economically, theocratic leadership played a crucial role in resource distribution and public works. Rulers often controlled surplus goods, such as maize, cacao, and textiles, which were redistributed during religious festivals or used to fund construction projects. These acts of generosity reinforced the ruler's divine mandate and ensured the loyalty of the populace. Furthermore, the construction of religious monuments and infrastructure projects provided employment and fostered a sense of communal identity, further solidifying theocratic rule.

In summary, theocratic leadership in Mesoamerica was a complex system where priests or divine rulers held political power, merging religion and governance into a single, cohesive structure. This model ensured that spiritual and administrative functions were inseparable, with rulers acting as both political leaders and religious figures. Through rituals, mythology, and hierarchical organization, theocratic leadership maintained order, legitimized authority, and shaped the cultural and social fabric of Mesoamerican societies. Its enduring legacy is evident in the monumental architecture, intricate art, and religious practices that continue to fascinate scholars and the public alike.

Washington's View: Were Political Parties Necessary for American Governance?

You may want to see also

Tribute Systems: Conquered regions paid resources to dominant empires like the Aztecs or Maya

Mesoamerica’s political organization was deeply intertwined with tribute systems, a cornerstone of how dominant empires like the Aztecs and Maya maintained control over conquered regions. These systems were not merely about extracting wealth but were structured mechanisms that reinforced political, economic, and social hierarchies. Conquered territories were obligated to provide regular payments in the form of resources, goods, or labor to the ruling empire. This practice ensured a steady flow of essential materials—such as food, textiles, precious metals, and exotic items—to the imperial center, sustaining its elite class, military, and religious institutions.

The Aztecs, for example, perfected a highly organized tribute system under the Triple Alliance, which consisted of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. Their tribute records, known as *matlatli*, were meticulously documented on codices, detailing the types and quantities of goods owed by each subject province. These goods ranged from agricultural products like maize and cacao to luxury items such as feathers, jade, and gold. The Aztecs used tribute not only to enrich their capital but also to demonstrate their power and integrate diverse ethnic groups into their empire. Failure to pay tribute often resulted in military intervention, ensuring compliance through a combination of coercion and diplomacy.

Similarly, the Maya city-states employed tribute systems to consolidate their authority over neighboring regions. Unlike the Aztecs, the Maya political landscape was more fragmented, with multiple city-states vying for dominance. Tribute in Maya society often included human resources, as captives from warfare were forced into labor or sacrificed in religious rituals. Material goods, such as quetzal feathers, copal incense, and textiles, were also collected to support the elite and fund public works like temples and palaces. The Maya tribute system was less centralized than the Aztec model but equally effective in maintaining regional control and projecting power.

Tribute systems served multiple purposes beyond resource extraction. They were a means of political integration, binding conquered regions to the imperial core through economic interdependence. By demanding specific goods unique to certain regions, empires like the Aztecs and Maya fostered specialization and trade networks, which in turn strengthened their economies. Additionally, tribute payments symbolized the submission of subject peoples to the ruling elite, reinforcing the ideological legitimacy of the empire. This was often tied to religious narratives, where rulers were seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people, further justifying the tribute demands.

The administration of tribute systems required sophisticated bureaucratic structures. Both the Aztecs and Maya developed complex institutions to manage the collection, storage, and redistribution of resources. Aztec tribute officials, known as *calpixque*, were stationed in subject territories to oversee the process and ensure compliance. The Maya, too, relied on a hierarchy of officials and scribes to maintain records and coordinate logistics. These systems were not static; they evolved over time in response to changing political and economic conditions, reflecting the adaptability of Mesoamerican empires in managing their vast territories.

In conclusion, tribute systems were a fundamental aspect of Mesoamerica’s political organization, enabling empires like the Aztecs and Maya to exert control, extract resources, and integrate diverse populations. These systems were not merely exploitative but were integral to the functioning of imperial economies and the projection of power. Through tribute, Mesoamerican empires maintained their dominance, fostered economic specialization, and reinforced their ideological authority, leaving a lasting legacy in the region’s history.

Munich Massacre's Political Aftermath: Birth of a New Party?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Military Conquest: Expansion through warfare to control territories and secure wealth and labor

Military conquest was a central mechanism of political organization and expansion in Mesoamerica, where warfare served as a primary means to control territories, secure resources, and consolidate power. Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Aztecs, Maya, and Zapotecs employed military campaigns to extend their influence, subjugate neighboring polities, and extract wealth and labor. Warfare was not merely about territorial gain but also about asserting dominance, securing tribute, and capturing prisoners for sacrifice or forced labor. The Aztecs, for instance, built their empire through relentless military campaigns, using their formidable army to conquer city-states across central Mexico. Their expansion was driven by the need to sustain their capital, Tenochtitlan, with resources like food, raw materials, and human labor.

The organization of military conquest in Mesoamerica was highly structured and often tied to the political and religious leadership. Rulers, such as the Aztec tlatoani or the Maya ajaw, frequently led or directed military campaigns to demonstrate their prowess and divine favor. Military success was closely linked to religious ideology, with victories attributed to the favor of gods who demanded offerings, including human sacrifices. Armies were composed of professional warriors, levied troops, and allies, with ranks and rewards based on valor and success in battle. Capturing enemy warriors was particularly prized, as prisoners could be used for sacrificial rituals to honor the gods or as laborers to support the conqueror’s economy.

Territorial control through military conquest was often formalized through tribute systems. Conquered polities were required to provide regular payments of goods, resources, and labor to the dominant power. For example, the Aztec Empire established a sophisticated tribute network, with detailed records of what each subject city owed. This system not only ensured a steady flow of wealth to the capital but also reinforced political control by integrating conquered regions into the empire’s administrative framework. Tribute items included agricultural products, luxury goods, and crafted items, which were redistributed to maintain the elite’s power and support the military apparatus.

Warfare in Mesoamerica was also a means of social and political mobility for individuals. Warriors who distinguished themselves in battle could rise through the ranks, gaining prestige, land, and access to elite privileges. For the Aztecs, the warrior class (eagle and jaguar warriors) held a privileged position in society, and military service was a pathway to honor and wealth. Similarly, rulers used military campaigns to solidify their legitimacy, as successful conquests were seen as evidence of their divine right to rule. This interplay between warfare, religion, and social hierarchy was a defining feature of Mesoamerican political organization.

Finally, the legacy of military conquest in Mesoamerica is evident in the enduring structures and systems left by empires like the Aztecs and Maya. Fortresses, ceremonial centers, and administrative hubs served as symbols of power and control, while the tribute and labor systems sustained the economic foundations of these civilizations. The collapse of Mesoamerican empires, such as the Aztec Empire following Spanish conquest, highlights the fragility of systems built on continuous military expansion and exploitation. Yet, the strategies and ideologies of military conquest remain a critical aspect of understanding Mesoamerica’s political organization and its impact on the region’s history.

Missouri's Political Party Registration: What Voters Need to Know

You may want to see also

Administrative Divisions: Hierarchical structures with local governors overseeing provinces for centralized empires

Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Aztec Empire, Maya city-states, and the Zapotec kingdom, developed sophisticated administrative divisions to manage their territories effectively. These systems were characterized by hierarchical structures where centralized empires appointed local governors to oversee provinces, ensuring political control, resource distribution, and tribute collection. At the apex of these hierarchies were rulers or emperors who held ultimate authority, while regional governors acted as intermediaries between the central power and local communities. This organizational model allowed Mesoamerican empires to govern vast and diverse territories efficiently, integrating conquered peoples into a cohesive political framework.

The Aztec Empire provides a prime example of this administrative system. It was divided into provinces known as *altepetl*, each governed by a local ruler or *tlatoani* who was often a vassal to the emperor in Tenochtitlan. These local rulers retained a degree of autonomy but were responsible for maintaining order, collecting tribute, and providing labor or military support to the central empire. Above them were high-ranking officials appointed by the emperor, such as the *calpixque*, who supervised tribute collection and ensured compliance with imperial decrees. This layered hierarchy facilitated the integration of diverse ethnic groups into the Aztec political system while maintaining centralized control.

In the Maya civilization, administrative divisions were less uniform due to the fragmented nature of Maya city-states, but hierarchical structures still played a crucial role. Powerful city-states like Tikal or Calakmul exerted influence over smaller polities through alliances, vassalage, or conquest. Local rulers, often drawn from the nobility, governed their territories while acknowledging the supremacy of the dominant city-state. These rulers were responsible for managing resources, organizing labor for public works, and participating in regional political networks. The Maya system, though less centralized than the Aztec model, relied on a similar principle of hierarchical oversight to maintain political cohesion.

The Zapotec kingdom of Monte Albán also employed a hierarchical administrative system to govern its territories in the Valley of Oaxaca. The Zapotec rulers established a network of provincial centers, each headed by a governor who administered local affairs and ensured the flow of tribute to the capital. These governors were often members of the elite class, appointed for their loyalty and administrative skills. The Zapotec system emphasized the integration of diverse communities through a combination of political control, economic interdependence, and cultural assimilation, mirroring the broader Mesoamerican trend of centralized empires relying on local governors to manage their provinces.

Across Mesoamerica, the success of these administrative divisions hinged on the ability of centralized empires to balance local autonomy with imperial authority. Local governors played a pivotal role in this dynamic, serving as the empire’s representatives in the provinces while also acting as advocates for their communities’ interests. This dual role helped maintain stability and ensured the efficient functioning of the political system. The hierarchical structures of Mesoamerican empires, therefore, were not merely tools of domination but also mechanisms for integrating diverse populations into a unified political and economic framework.

In conclusion, the administrative divisions of Mesoamerican centralized empires were built on hierarchical structures where local governors oversaw provinces under the authority of a central ruler. This system allowed empires like the Aztecs, Maya, and Zapotecs to manage extensive territories, collect resources, and maintain political control. By delegating authority to trusted local leaders while retaining ultimate power, Mesoamerican civilizations created resilient political organizations that endured for centuries, shaping the region’s history and legacy.

Polarized Perspectives: How Politics Creates Deep Divides in Society

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mesoamerica featured diverse political systems, including city-states, empires, and tributary states. City-states, like Teotihuacan and Monte Albán, were independent political units centered around a capital city. Empires, such as the Aztec Empire, were larger, centralized systems that controlled multiple regions through military conquest and tribute. Tributary states were smaller polities that paid resources or labor to a dominant power in exchange for protection or autonomy.

The Aztec Empire was organized as a hierarchical, centralized state with the emperor (tlatoani) at the top, ruling from the capital city of Tenochtitlan. Below the emperor were nobles and priests who administered provinces and cities. The empire expanded through military campaigns, integrating conquered territories into a system of tribute and labor. Local rulers were often allowed to retain power as long as they pledged loyalty and paid tribute to the Aztec capital.

Religion was deeply intertwined with politics in Mesoamerica, legitimizing rulers' authority and justifying political structures. Rulers often claimed divine descent or a mandate from the gods, reinforcing their power. Religious institutions, such as temples and priesthoods, were central to governance, and major political decisions were often tied to religious rituals or prophecies. Additionally, religious calendars and ceremonies helped maintain social order and political control.

![Sid Meier's Civilization VII Deluxe - PC [Online Game Code]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/916xC0qTKsL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Civilization [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91Y6yepZCaL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Sid Meier's Civilization® VII Standard - PC [Online Game Code]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81iJV77IRrL._AC_UY218_.jpg)