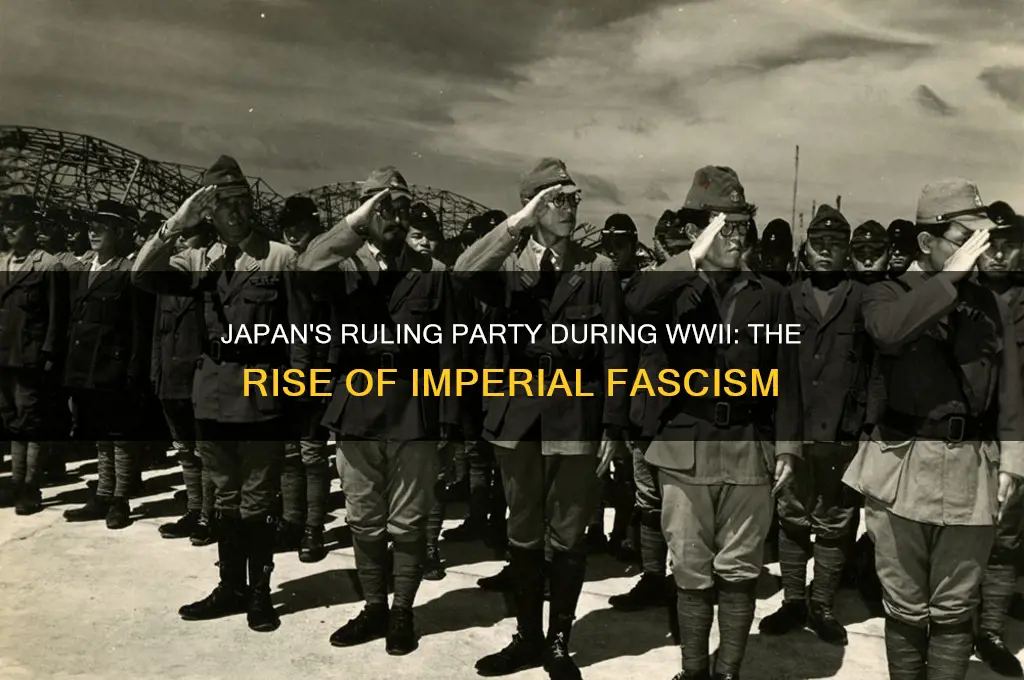

During World War II, Japan was dominated by a single-party system under the Taisei Yokusankai, or the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, established in 1940. This organization was not a traditional political party but rather a totalitarian movement designed to unify all political factions under Emperor Hirohito's authority. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe created it to eliminate dissent and consolidate power, effectively dissolving all other political parties. The Taisei Yokusankai promoted ultra-nationalism, militarism, and the war effort, reflecting the government's authoritarian control over Japanese society until the nation's surrender in 1945.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Imperial Rule Assistance Association (IRAA) / 大政翼賛会 (Taisei Yokusankai) |

| Type | Single-party dictatorship |

| Ideology | Japanese nationalism, Statism, Militarism, Fascism, Anti-communism |

| Founded | October 12, 1940 |

| Dissolved | June 13, 1945 |

| Leader | Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe (initial) |

| Successor | Various parties after WWII, including the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) |

| Political Position | Far-right |

| Key Figures | Hideki Tojo, Nobuyuki Abe, Mitsumasa Yonai |

| Goals | Totalitarian control, Expansionism, Promotion of Japanese cultural superiority |

| Role in WWII | Supported Japan's militaristic policies and war efforts |

| Relationship with Emperor | Claimed to act in the Emperor's name, though the Emperor's direct involvement was limited |

| Opposition | Suppressed all opposition parties and dissent |

| Legacy | Disbanded after Japan's surrender in WWII, viewed as a symbol of Japan's wartime authoritarianism |

Explore related products

$13.39 $22.99

$27.59 $29.99

What You'll Learn

- Rise of Militarism: Nationalist and militarist factions gained control, influencing political decisions and foreign policy

- Taisei Yokusankai: Government-sponsored party formed in 1940 to unify political organizations under authoritarian rule

- Imperial Rule Assistance Association: Promoted totalitarianism, dissolved all parties except itself, aligning with the Emperor

- Key Figures: Leaders like Hideki Tojo and Fumimaro Konoe shaped Japan’s wartime political direction

- Post-War Dissolution: Taisei Yokusankai disbanded in 1945, leading to democratic reforms under Allied occupation

Rise of Militarism: Nationalist and militarist factions gained control, influencing political decisions and foreign policy

During the lead-up to and throughout World War II, Japan’s political landscape was dominated by the rise of militarism, a phenomenon driven by nationalist and militarist factions that seized control of key institutions. These groups, often rooted in the military and ultra-nationalist organizations, systematically eroded civilian authority and reshaped foreign policy to prioritize expansionism and imperial ambitions. The Imperial Japanese Army and Navy became political power brokers, with officers influencing or outright intimidating politicians to align with their aggressive agenda. This shift was not sudden but a gradual process fueled by economic crises, ideological fervor, and a manipulated narrative of national destiny.

To understand this rise, consider the role of institutions like the *Toseiha* and *Kodoha* factions within the military. The *Kodoha* (Imperial Way) faction, in particular, advocated for a totalitarian state under the Emperor and expansion into Asia to secure resources. Their influence culminated in incidents like the 1936 February 26 coup attempt, which, though unsuccessful, demonstrated the military’s willingness to use force to shape politics. Civilian governments, weakened by corruption scandals and economic instability, were increasingly sidelined. The military’s direct representation in the cabinet, through posts like the Army and Navy Ministers, ensured their veto power over policies, effectively hijacking decision-making.

A critical turning point was the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, orchestrated by rogue elements in the Kwantung Army without approval from Tokyo. This act of insubordination was retroactively endorsed by the government, setting a precedent for military autonomy in foreign affairs. The subsequent withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933 symbolized Japan’s rejection of international norms in favor of unilateral aggression. Nationalist propaganda, disseminated through education and media, glorified military service and portrayed expansion as a sacred duty to the Emperor, further entrenching militarist ideology in public consciousness.

The practical implications of this militarist control were devastating. Resources were diverted to fund wars in China and later the Pacific, exacerbating domestic shortages. Political dissent was brutally suppressed, with laws like the Peace Preservation Act criminalizing anti-war speech. The military’s dominance also led to strategic miscalculations, such as the decision to attack Pearl Harbor, which, while a tactical success, drew the United States into the war and sealed Japan’s eventual defeat. This period underscores the dangers of allowing unelected, ideological factions to dictate national policy, a lesson relevant to any society grappling with the balance between military power and democratic governance.

Understanding the Non-Partisan Political Party: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Taisei Yokusankai: Government-sponsored party formed in 1940 to unify political organizations under authoritarian rule

During World War II, Japan's political landscape was dominated by the Taisei Yokusankai, a government-sponsored party established in 1940 with the explicit goal of unifying all political organizations under a single, authoritarian rule. This move was part of a broader effort to consolidate power and eliminate dissent as Japan deepened its militaristic expansion. The party, often translated as the "Imperial Rule Assistance Association," was not a traditional political party but rather a tool of the state, designed to mobilize the population in support of the war effort and the emperor's authority. Its creation marked the end of multiparty politics in Japan, replacing it with a system that prioritized national unity and obedience to the government's directives.

The formation of the Taisei Yokusankai was a strategic response to the perceived need for centralized control during a time of war. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, who spearheaded its creation, argued that traditional political parties were divisive and hindered Japan's ability to wage war effectively. By dissolving existing parties and merging them into a single organization, the government aimed to create a unified front that could rally the nation behind its militaristic agenda. The party's structure was hierarchical, with the emperor at its apex, and its ideology was rooted in Kokutai (national polity), emphasizing the divine nature of the emperor and the superiority of Japanese culture. This ideological framework was used to justify both domestic repression and foreign aggression.

One of the most striking aspects of the Taisei Yokusankai was its role in mobilizing the Japanese population for total war. The party established local branches across the country, infiltrating communities, workplaces, and schools to ensure compliance with government policies. It promoted slogans like "Luxury is the Enemy" and encouraged citizens to sacrifice personal comforts for the war effort. Women were organized into groups like the Greater Japan Women’s Association, where they were taught to prioritize their roles as mothers of soldiers and contributors to the home front. Even children were enlisted through organizations like the Young Men’s and Girls’ Associations, which indoctrinated them with militaristic values and prepared them for future service.

Despite its emphasis on unity, the Taisei Yokusankai faced internal challenges and contradictions. Factionalism persisted within its ranks, as conservative bureaucrats, militarists, and ultranationalists vied for influence. Additionally, the party's attempts to control every aspect of society often led to inefficiencies and resentment among the population. For example, its efforts to regulate daily life, such as dictating clothing styles and food consumption, were seen as intrusive and impractical. By the later stages of the war, as Japan's military situation deteriorated, the party's ability to maintain its grip on society weakened, and its promises of victory rang hollow.

In retrospect, the Taisei Yokusankai serves as a cautionary example of the dangers of authoritarianism and the suppression of political pluralism. Its creation was a pivotal moment in Japan's wartime history, illustrating how a government can exploit national crises to consolidate power and impose uniformity. While it achieved its short-term goal of unifying the nation under a single banner, it did so at the cost of individual freedoms and democratic institutions. The party's legacy underscores the importance of safeguarding political diversity and civil liberties, even in times of crisis, as the alternative can lead to unchecked power and devastating consequences.

Understanding Political Governance: How Parties Shape Policy and Leadership

You may want to see also

Imperial Rule Assistance Association: Promoted totalitarianism, dissolved all parties except itself, aligning with the Emperor

During World War II, Japan's political landscape was dominated by the Imperial Rule Assistance Association (IRAA), a single-party organization that epitomized the nation's slide into totalitarianism. Established in 1940 under Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, the IRAA was not merely a political party but a state-sponsored apparatus designed to consolidate power and eliminate dissent. Its primary objective was to unify the nation under the absolute authority of the Emperor, dissolving all existing political parties and suppressing opposition. This move effectively ended Japan's brief experiment with multi-party democracy, which had been in place since the Meiji era, and ushered in a regime characterized by rigid control and militaristic nationalism.

The IRAA's structure and ideology were meticulously crafted to enforce conformity and loyalty to the Emperor. It operated as a mass organization, mobilizing citizens from all walks of life—from bureaucrats to farmers—into a hierarchical system that mirrored the military. Members were required to pledge allegiance to the Emperor and adhere to the principles of *Kokutai* (national polity), which emphasized the divine nature of the Emperor and the uniqueness of the Japanese nation. By dissolving all other political parties and absorbing their members into the IRAA, the regime sought to eliminate ideological diversity and create a monolithic political entity. This was not just a political maneuver but a cultural and social reengineering effort to ensure that every Japanese citizen was a loyal subject of the Emperor.

One of the most striking aspects of the IRAA was its role in promoting totalitarianism through the suppression of individual freedoms and the centralization of power. The association controlled all aspects of public life, from education and media to labor unions and local governance. Propaganda was pervasive, glorifying the war effort and portraying dissent as treasonous. The IRAA's influence extended into households, with neighborhood associations (*tonarigumi*) acting as surveillance units to monitor and report any behavior deemed unpatriotic. This pervasive control mechanism ensured that the regime's ideology penetrated every corner of society, leaving no room for dissent or alternative viewpoints.

A comparative analysis of the IRAA with other totalitarian regimes of the era, such as Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy, reveals both similarities and unique characteristics. While all three regimes sought to centralize power and suppress opposition, the IRAA's alignment with the Emperor as a divine figure gave it a distinct religious and cultural dimension. Unlike the Führer or Duce, the Emperor was not a political leader but a spiritual symbol, which allowed the IRAA to frame its totalitarianism as a sacred duty rather than a political ideology. This spiritual underpinning made the regime's control more insidious, as it appealed to deeply ingrained cultural values and traditions.

In conclusion, the Imperial Rule Assistance Association was a cornerstone of Japan's totalitarian regime during World War II, embodying the nation's shift toward absolute militarism and Emperor-centric nationalism. By dissolving all political parties and enforcing ideological uniformity, the IRAA eliminated any semblance of democracy and established a system of total control. Its legacy serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked power and the erosion of individual freedoms in the name of national unity. Understanding the IRAA's role provides critical insights into the mechanisms of totalitarianism and the ways in which political, cultural, and spiritual elements can be manipulated to consolidate authority.

Understanding 'Bolt the Party': Political Disaffiliation and Its Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Key Figures: Leaders like Hideki Tojo and Fumimaro Konoe shaped Japan’s wartime political direction

During World War II, Japan's political landscape was dominated by the Imperial Rule Assistance Association (Taisei Yokusankai), a statist, authoritarian organization that effectively functioned as a single-party regime. At the helm of this structure were key figures whose decisions and ideologies profoundly shaped Japan's wartime trajectory. Among them, Hideki Tojo and Fumimaro Konoe stand out as pivotal leaders whose actions and visions left an indelible mark on the nation's history.

The Architect of Expansion: Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo, serving as Prime Minister from 1941 to 1944, was a staunch militarist and the embodiment of Japan's aggressive wartime policies. His rise to power coincided with Japan's deepening commitment to expansionism, culminating in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Tojo's leadership was characterized by his unwavering belief in Japan's divine mission to dominate Asia. As Army Minister and later Prime Minister, he consolidated military and political power, silencing dissent and pushing for total war mobilization. His decision to ally with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy through the Tripartite Pact further entrenched Japan in the global conflict. Tojo's relentless pursuit of victory, even in the face of overwhelming odds, exemplified the militarist ideology that drove Japan's wartime actions.

The Reluctant Facilitator: Fumimaro Konoe

Fumimaro Konoe, who served as Prime Minister in two terms before Tojo, played a different but equally critical role in Japan's wartime political direction. Konoe was a moderate who initially sought to balance Japan's expansionist ambitions with diplomatic solutions. However, his inability to rein in the military's influence led to policies that paved the way for war. Notably, Konoe's government enacted the National Mobilization Law in 1938, which centralized control over the economy and society, laying the groundwork for total war. His resignation in 1941, after failing to secure a peace agreement with the United States, marked a turning point, as it cleared the path for Tojo's hardline leadership. Konoe's legacy is one of a leader who, despite his reservations, enabled the militarists' rise to power.

Comparing Legacies: Tojo vs. Konoe

While both Tojo and Konoe were instrumental in shaping Japan's wartime policies, their approaches and legacies differ starkly. Tojo was a decisive militarist whose actions directly led to Japan's entry into World War II, earning him a reputation as a war criminal and ultimately leading to his execution in 1948. In contrast, Konoe's role was more nuanced; he was a pragmatist who sought to avoid war but lacked the political strength to counter the military's dominance. His later efforts to end the war, including his role in drafting Japan's surrender petition in 1945, highlight his complex legacy as a leader caught between competing forces.

Takeaway: Leadership and Responsibility

The roles of Tojo and Konoe underscore the profound impact of individual leadership on a nation's course during times of crisis. Tojo's unyielding militarism and Konoe's inability to challenge the status quo illustrate how leaders' ideologies and actions can either escalate or mitigate conflict. For historians and policymakers alike, their stories serve as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked militarism and the importance of strong, principled leadership in navigating global tensions. Understanding their roles provides critical insights into the complexities of Japan's wartime decisions and their enduring consequences.

1799 Political Landscape: Parties Shaping Early 19th-Century Governance

You may want to see also

Post-War Dissolution: Taisei Yokusankai disbanded in 1945, leading to democratic reforms under Allied occupation

The dissolution of the Taisei Yokusankai (Imperial Rule Assistance Association) in 1945 marked a pivotal moment in Japan's political history, signaling the end of an era dominated by militarism and authoritarianism. Established in 1940 under Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, the Taisei Yokusankai was designed to unify all political parties and organizations under a single, state-sponsored entity, effectively eliminating opposition and centralizing power. This move was a cornerstone of Japan's wartime mobilization strategy, aligning the nation under the Emperor's absolute authority and promoting ultra-nationalist ideologies. However, its disbandment following Japan's surrender in World War II was not merely an administrative act but a necessary step toward dismantling the structures that had enabled the war.

The Allied occupation forces, led by the United States, played a critical role in this transformation. Under the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers (SCAP), Japan was compelled to adopt democratic reforms that starkly contrasted with the Taisei Yokusankai's authoritarian framework. The occupation authorities prioritized the dissolution of wartime institutions, the liberation of political prisoners, and the establishment of a multiparty system. The Japanese government, now under Allied supervision, was tasked with drafting a new constitution that enshrined principles such as pacifism, popular sovereignty, and fundamental human rights. This process was not just about rewriting laws but about reshaping the nation's political culture, moving away from militarism and toward a democratic society.

One of the most significant outcomes of this period was the 1947 Constitution of Japan, often referred to as the "Peace Constitution." Article 9, in particular, renounced Japan's right to wage war and maintain military forces, a direct response to the aggressive policies enabled by the Taisei Yokusankai. This constitutional shift was accompanied by the revival of political parties, which had been suppressed during the war. The Japan Socialist Party, the Liberal Party, and other groups emerged, offering citizens alternatives to the monolithic control of the past. These reforms were not without challenges, as they required a fundamental reorientation of Japanese society, but they laid the groundwork for the democratic stability Japan enjoys today.

The disbandment of the Taisei Yokusankai also had profound social implications. The wartime regime had fostered a culture of conformity and obedience, often at the expense of individual freedoms. Post-war reforms sought to reverse this trend by promoting education, labor rights, and gender equality. For instance, women gained the right to vote in 1946, a landmark achievement that reflected the broader democratization process. Similarly, labor unions were legalized, empowering workers to negotiate for better conditions and challenge corporate dominance. These changes were not instantaneous, but they represented a deliberate effort to rebuild Japan on a foundation of equality and justice.

In retrospect, the dissolution of the Taisei Yokusankai was more than just the end of a political party; it was the beginning of Japan's journey toward democracy. The Allied occupation, while externally imposed, catalyzed reforms that aligned with the aspirations of many Japanese citizens for a peaceful and free society. The legacy of this period is evident in Japan's modern political system, which, despite its challenges, remains a testament to the transformative power of democratic ideals. For those studying political transitions, Japan's post-war experience offers valuable lessons on how authoritarian structures can be dismantled and replaced with institutions that prioritize human rights and collective well-being.

Unveiling Bongbong Marcos' Political Affiliation: A Comprehensive Party Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Japan did not have a dominant political party during World War II. Instead, it was governed by a militaristic regime led by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, with the Emperor as the symbolic head of state.

No, Japan did not have a functioning multi-party system during World War II. Political parties were largely suppressed, and the government was controlled by military leaders and bureaucrats.

The Taisei Yokusankai (Imperial Rule Assistance Association) was established in 1940 as a single, state-sponsored political organization to unify the country under the Emperor's rule. It effectively replaced political parties and promoted the militarist agenda.

No, opposition parties were virtually non-existent during World War II. The government tightly controlled political activity, and dissent was harshly suppressed.

After World War II, Japan transitioned to a democratic system under the Allied occupation. The 1947 Constitution established a parliamentary democracy, allowing for the reemergence of political parties and free elections.