Ernest Hemingway's politics were complex and often ambiguous, reflecting his personal experiences, disillusionment with war, and a deep-seated individualism. While he was not overtly partisan, Hemingway's works and public statements suggest a mix of conservative and progressive leanings. He admired courage, self-reliance, and traditional values, often aligning with conservative ideals, yet he also criticized imperialism, fascism, and the excesses of capitalism. His coverage of the Spanish Civil War revealed a sympathy for the Republican cause against Franco’s nationalist forces, though he grew disillusioned with ideological extremism. Hemingway’s later years saw him increasingly skeptical of government and authority, particularly during the Cold War era, when he faced scrutiny from the FBI. Ultimately, his politics were shaped by his role as an observer of human suffering and his belief in the dignity of the individual, making him difficult to categorize neatly within a single political framework.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Affiliation | Hemingway's political views were complex and not easily categorized. He was often associated with conservatism but also expressed admiration for leftist figures and movements. |

| Anti-Fascism | Strongly opposed fascism, as evidenced by his involvement in the Spanish Civil War and his novel "For Whom the Bell Tolls." |

| Skepticism of Communism | While initially sympathetic to the Soviet Union, he became disillusioned with communism, particularly after his experiences in Spain. |

| Individualism | Valued personal freedom and individualism, often reflected in his characters who embody self-reliance and resilience. |

| Criticism of Totalitarianism | Opposed all forms of totalitarianism, whether fascist or communist, viewing them as threats to individual liberty. |

| Support for the Spanish Republic | Actively supported the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War, fighting against Franco's Nationalist forces. |

| Ambivalence Toward the U.S. Government | Criticized certain U.S. policies, particularly during the Cold War, while maintaining a deep love for his country. |

| Admiration for Courage and Honor | Valued courage, honor, and integrity, often glorifying these traits in his writing and personal life. |

| Environmental Conservation | Later in life, Hemingway expressed concern for environmental conservation, particularly in his love for nature and outdoor pursuits. |

| Skepticism of Organized Religion | While not an atheist, he was skeptical of organized religion, often portraying it as hypocritical or ineffectual in his works. |

| Support for Social Justice | Showed empathy for the underprivileged and marginalized, though his views were not consistently aligned with any specific social justice movement. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Hemingway's views on fascism and totalitarianism

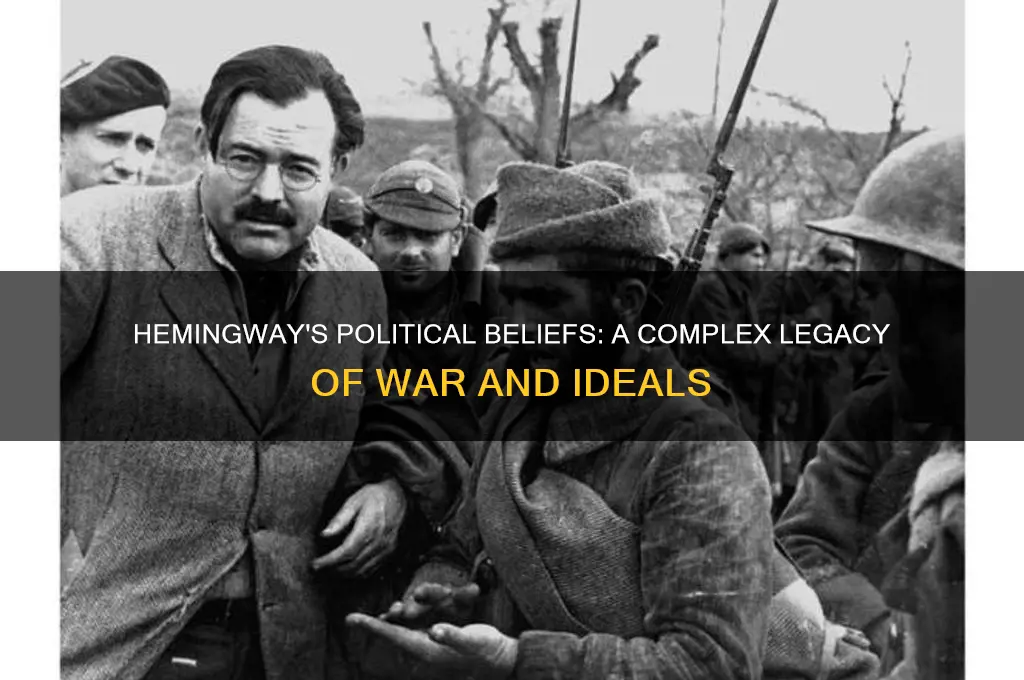

Ernest Hemingway’s views on fascism and totalitarianism were deeply shaped by his experiences as a journalist and writer during the tumultuous political events of the early 20th century, particularly the Spanish Civil War and World War II. Hemingway was an outspoken critic of fascism, which he saw as a destructive and dehumanizing force. His novel *For Whom the Bell Tolls* (1940), set during the Spanish Civil War, reflects his staunch opposition to Francisco Franco’s fascist regime, which he viewed as oppressive and antithetical to individual freedom. Hemingway aligned himself with the Republican cause, which fought against Franco’s Nationalist forces, and his portrayal of the war highlights the moral and human cost of fascism.

Hemingway’s antipathy toward fascism extended beyond Spain. During World War II, he actively supported the Allied effort against Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, both fascist regimes. His journalism and writings from this period, including his dispatches from the front lines, underscore his belief that fascism represented a grave threat to democracy and human dignity. Hemingway’s participation in the liberation of Paris in 1944 further solidified his commitment to defeating totalitarian ideologies. He saw fascism as a system that crushed individuality, suppressed dissent, and glorified violence, values that were diametrically opposed to his own.

While Hemingway was a critic of fascism, his views on totalitarianism were more nuanced. He was skeptical of all forms of authoritarianism, including communism, despite his initial sympathy for the Soviet Union’s role in fighting fascism. By the late 1940s, Hemingway grew disillusioned with the Soviet regime’s totalitarian tendencies, particularly its suppression of individual freedoms and artistic expression. This shift is evident in his later works, such as *The Old Man and the Sea* (1952), which emphasize personal resilience and independence over collective ideologies.

Hemingway’s opposition to fascism and totalitarianism was rooted in his belief in the inherent value of the individual. He admired courage, integrity, and the human spirit’s ability to endure in the face of oppression. His characters often embody these traits, standing as symbols of resistance against oppressive systems. For Hemingway, the fight against fascism and totalitarianism was not just a political struggle but a moral one, centered on preserving human dignity and freedom.

In summary, Hemingway’s views on fascism and totalitarianism were marked by a deep-seated rejection of authoritarianism and a commitment to individual liberty. His experiences in Spain and during World War II shaped his understanding of fascism as a destructive force, while his later disillusionment with the Soviet Union broadened his critique to include all forms of totalitarianism. Through his writing and actions, Hemingway articulated a vision of humanity that valued courage, freedom, and the resilience of the individual against oppressive regimes.

Equality in Politics: Why Fair Representation Shapes a Just Society

You may want to see also

His stance on the Spanish Civil War

Ernest Hemingway’s stance on the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) was deeply rooted in his antifascist beliefs and his commitment to the Republican cause. He viewed the conflict as a pivotal struggle between democracy and fascism, a perspective that aligned with his broader political sympathies. Hemingway traveled to Spain in 1937 to cover the war as a journalist for the *North American Newspaper Alliance*, but his involvement went far beyond mere observation. He became an outspoken advocate for the Republicans, who were fighting against General Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces, which were backed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Hemingway’s experiences during this period profoundly influenced his writing, most notably in his novel *For Whom the Bell Tolls*, which immortalized the war and its ideals.

Hemingway’s support for the Republicans was not just ideological but also personal. He was appalled by the rise of fascism in Europe and saw the Spanish Civil War as a critical battleground to halt its spread. He believed that the Nationalists, under Franco, represented a repressive and authoritarian regime that threatened the freedoms and rights of the Spanish people. In contrast, he admired the Republicans for their fight to preserve Spain’s democratic republic, even though the coalition included diverse factions, from socialists and communists to anarchists. Hemingway’s antifascism was uncompromising, and he saw the war as a moral imperative, a fight for justice against tyranny.

His involvement in the war extended to practical support. Hemingway helped raise funds for the Republican cause and even assisted in the production of the documentary *The Spanish Earth*, which aimed to garner international sympathy and aid for the Republicans. He also used his writing as a weapon, crafting dispatches and articles that highlighted the atrocities committed by the Nationalists and the resilience of the Republican fighters. His work during this period was not just journalistic but also propagandistic, aimed at mobilizing public opinion in favor of the Republican side.

Hemingway’s novel *For Whom the Bell Tolls* is perhaps the most enduring testament to his stance on the Spanish Civil War. Published in 1940, the book tells the story of Robert Jordan, an American volunteer fighting with the Republicans. Through Jordan’s character, Hemingway explores themes of sacrifice, solidarity, and the moral clarity of the Republican cause. The novel’s title, taken from John Donne’s meditation on interconnectedness, underscores Hemingway’s belief that the struggle in Spain was not isolated but had global implications. The book became a rallying cry for antifascists worldwide and cemented Hemingway’s reputation as a writer deeply engaged with the political and moral issues of his time.

Despite his passionate commitment, Hemingway was not blind to the complexities of the war. He recognized the internal divisions within the Republican camp and the challenges posed by the Soviet Union’s involvement, which often prioritized Stalin’s interests over the broader goals of the Spanish Republicans. However, these complexities did not diminish his conviction that the Republican cause was just. For Hemingway, the Spanish Civil War was a defining moment of the 20th century, a clash of ideologies that demanded a clear moral stance. His unwavering support for the Republicans reflected his broader antifascist politics and his belief in the necessity of resisting oppression, no matter the cost.

FDR's Political Ideology: Liberalism, Progressivism, and the New Deal Era

You may want to see also

Hemingway's relationship with Cuban politics

Ernest Hemingway’s relationship with Cuban politics was complex, deeply personal, and reflective of his broader political outlook, which was often characterized as ambiguous and evolving. Hemingway first arrived in Cuba in the 1930s and quickly fell in love with the island, eventually making it his home in 1939. During this period, Cuba was a nation in flux, grappling with political instability, corruption, and foreign influence, particularly from the United States. Hemingway’s engagement with Cuban politics was shaped by his experiences, his friendships with locals, and his observations of the socio-economic realities of the time.

Initially, Hemingway’s political stance in Cuba was not overtly ideological. He was more of an observer than an activist, though he sympathized with the struggles of the Cuban people. His novel *The Old Man and the Sea*, written in Cuba, reflects his admiration for the resilience and dignity of ordinary Cubans, particularly those in marginalized communities. However, as the 1940s and 1950s progressed, Hemingway became increasingly aware of the political tensions brewing on the island, particularly the growing resistance to the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. Hemingway’s disdain for Batista’s regime became evident in his private correspondence and conversations, though he rarely spoke out publicly.

Hemingway’s most significant political alignment in Cuba came with his support for the Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro. While he did not directly participate in revolutionary activities, Hemingway’s sympathies lay with the revolutionaries, whom he saw as fighting against corruption and imperialism. After the revolution’s success in 1959, Hemingway developed a personal relationship with Castro, whom he admired for his charisma and determination. Hemingway’s famous statement, “Now we are all Cubans,” following the revolution, underscored his solidarity with the new government. However, his support was not unconditional; he remained critical of certain aspects of the regime, particularly its treatment of dissenters.

Despite his affinity for the revolutionary cause, Hemingway’s relationship with Cuban politics was marked by a sense of detachment. He saw himself as an outsider, a role that allowed him to observe and write about Cuba without becoming entangled in its political machinery. This detachment is evident in his reluctance to fully commit to any political ideology, even as he expressed admiration for the revolutionary spirit. Hemingway’s politics in Cuba were thus characterized by a blend of empathy for the Cuban people, skepticism of authoritarianism, and a deep love for the island’s culture and landscape.

In his later years, Hemingway’s health declined, and his engagement with Cuban politics waned. However, his legacy in Cuba remains significant. The Cuban government has preserved his home, Finca Vigía, as a museum, and Hemingway is celebrated as a cultural icon who captured the essence of Cuba in his writings. His relationship with Cuban politics reflects his broader worldview: a mix of idealism, pragmatism, and a profound connection to the places and people he loved. Hemingway’s Cuba was not just a backdrop for his life and work but a source of inspiration and a testament to his enduring fascination with the human condition in times of political upheaval.

Unveiling Joe Polito: Life, Achievements, and Impact Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Views on American foreign policy

Ernest Hemingway’s views on American foreign policy were shaped by his experiences as a war correspondent, his time spent in Europe, and his disillusionment with the idealism of American interventionism. While Hemingway was not a political theorist, his writings and public statements reflect a complex and often critical perspective on U.S. foreign policy, particularly during the interwar period and World War II. Hemingway’s politics were deeply influenced by his firsthand observations of the human cost of war and his skepticism of nationalist rhetoric.

One of Hemingway’s central critiques of American foreign policy was its tendency toward moralistic interventionism. He was wary of the United States positioning itself as a global arbiter of democracy, especially when such actions were driven by self-interest rather than genuine altruism. In his novel *For Whom the Bell Tolls*, set during the Spanish Civil War, Hemingway portrays American involvement in foreign conflicts as often misguided and detached from the realities on the ground. He believed that U.S. policy frequently failed to account for the complexities of local politics and cultures, leading to unintended consequences and suffering.

Hemingway’s experiences in Spain during the 1930s profoundly shaped his views on American foreign policy. He was a staunch supporter of the Republican cause against Francisco Franco’s fascist forces, yet he was critical of the U.S. government’s neutrality, which he saw as tacit support for fascism. Hemingway’s disillusionment with American inaction in Spain foreshadowed his later skepticism of U.S. foreign policy during World War II. While he supported the Allied effort against Nazi Germany, he remained critical of the idealistic rhetoric surrounding the war, arguing that it obscured the brutal realities of conflict.

During the Cold War, Hemingway’s views on American foreign policy grew increasingly skeptical. He was critical of the U.S. government’s anti-communist crusade, which he saw as driven by paranoia and a desire for global dominance rather than a genuine commitment to freedom. In his later years, Hemingway expressed frustration with the militarization of U.S. foreign policy and its tendency to prioritize geopolitical interests over human lives. His novel *The Old Man and the Sea* can be read as a metaphor for the individual’s struggle against overwhelming forces, a theme that reflects his broader critique of power dynamics in international relations.

Hemingway’s stance on American foreign policy was also marked by a deep sense of ambiguity. While he was critical of U.S. interventionism, he was not a pacifist, and he recognized the necessity of fighting against tyranny. This tension is evident in his portrayal of war in works like *A Farewell to Arms* and *The Sun Also Rises*, where he depicts the heroism of individuals while condemning the systems that lead to conflict. Hemingway’s politics were ultimately rooted in his belief in personal integrity and the importance of bearing witness to the truth, values that often clashed with the ideological posturing of American foreign policy.

In summary, Hemingway’s views on American foreign policy were characterized by skepticism, disillusionment, and a commitment to exposing the human cost of political decisions. His experiences in war-torn Europe and his observations of U.S. actions during the 20th century led him to critique American interventionism, moralistic rhetoric, and the pursuit of global dominance. While he supported the fight against fascism, he remained wary of the idealism and self-interest that often drove U.S. foreign policy. Hemingway’s writings continue to offer a powerful critique of the complexities and contradictions inherent in America’s role on the world stage.

Who is Clear Politics? Unveiling the Platform's Role in Political Analysis

You may want to see also

His perspective on individualism and freedom

Ernest Hemingway’s perspective on individualism and freedom was deeply intertwined with his personal experiences, his writing, and the broader political and cultural contexts of his time. Hemingway, a staunch individualist, believed in the primacy of personal courage, self-reliance, and the ability to endure in the face of adversity. His characters, often solitary figures like Santiago in *The Old Man and the Sea* or Jake Barnes in *The Sun Also Rises*, embody this ethos, navigating their struggles with a quiet, unyielding determination. For Hemingway, true freedom was not merely the absence of external constraints but the internal strength to confront life’s challenges with grace and resilience.

Hemingway’s individualism was rooted in his rejection of societal expectations and conformity. He admired those who lived authentically, unapologetically charting their own course, even if it meant isolation or misunderstanding. This perspective is evident in his portrayal of expatriates in his novels, who often break away from the constraints of their home cultures to seek a more genuine existence abroad. Hemingway’s own life, marked by his travels, his rejection of traditional career paths, and his embrace of physical pursuits like hunting and bullfighting, reflects this commitment to personal freedom and self-definition.

Freedom, for Hemingway, was also tied to the idea of personal responsibility. He believed that individuals must take ownership of their actions and their fate, a theme recurrent in his works. In *For Whom the Bell Tolls*, Robert Jordan’s decision to fight in the Spanish Civil War is an act of both personal and political freedom, driven by his sense of duty and moral clarity. Hemingway’s characters often face existential crises, but their freedom lies in their ability to choose how to respond, even in the face of inevitable defeat or death.

Hemingway’s politics, while not explicitly ideological, leaned toward a conservative understanding of individualism, emphasizing personal honor and integrity over collective or state-driven solutions. He was skeptical of large-scale political movements, particularly those that sought to impose uniformity or restrict personal autonomy. His experiences in war-torn Europe and his observations of totalitarian regimes reinforced his belief in the importance of individual liberty as a bulwark against oppression. This perspective is reflected in his disdain for fascism and communism, which he saw as threats to the kind of personal freedom he valued.

Ultimately, Hemingway’s perspective on individualism and freedom was both philosophical and practical. It was about living fully, honestly, and on one’s own terms, even in a world that often demanded compromise. His writing celebrates the individual’s capacity to find meaning and dignity in a seemingly indifferent universe, a testament to his belief that true freedom is an internal state, cultivated through courage, discipline, and a refusal to yield to external pressures. In Hemingway’s worldview, the individual’s struggle for freedom is not just a personal quest but a universal one, resonating across time and circumstance.

How Political Strategies and Policies Ended the 2008 Recession

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hemingway's politics were complex and evolved over time. He was initially sympathetic to leftist causes, supporting the Republican faction during the Spanish Civil War and expressing admiration for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. However, he later became disillusioned with communism and was critical of totalitarian regimes, including both fascist and communist governments.

While Hemingway was sympathetic to leftist causes and the Soviet Union during the 1930s, he was not a committed communist. His views shifted over time, and he grew increasingly critical of Soviet policies, particularly after witnessing the suppression of individual freedoms in communist regimes.

Hemingway's political beliefs often informed his work, particularly in novels like *For Whom the Bell Tolls*, which reflects his support for the Spanish Republicans. His writing frequently explores themes of justice, resistance, and the human cost of political conflict, though he avoided overt political propaganda, focusing instead on the personal experiences of his characters.