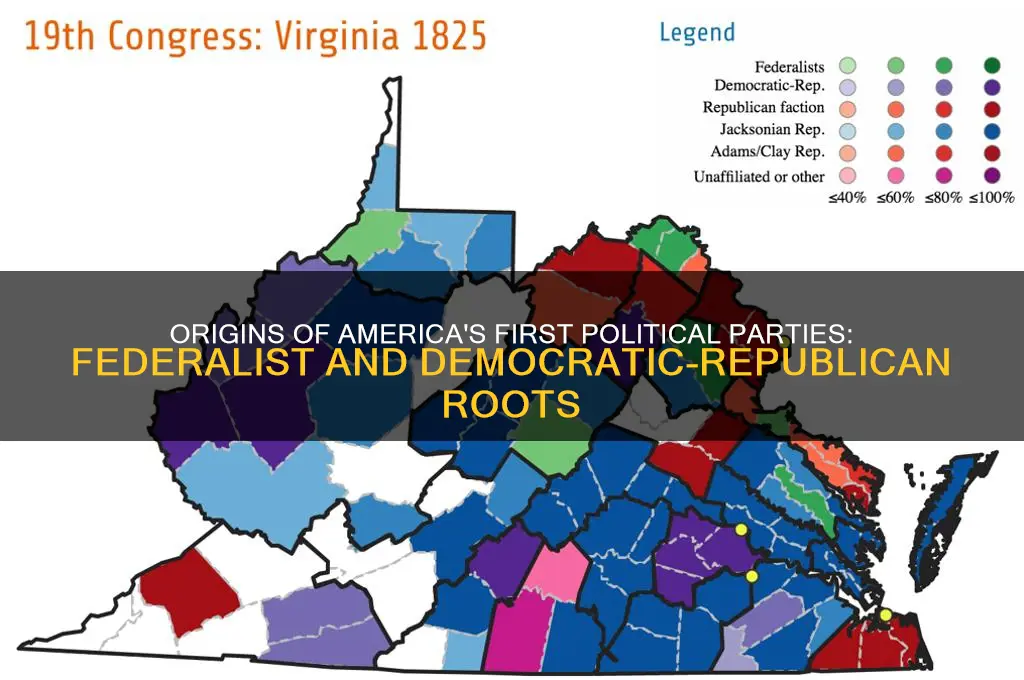

The formation of the first two political parties in the United States emerged from deep ideological divisions over the role and structure of the federal government during the early years of the republic. The Federalist Party, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain, reflecting their belief in a robust, industrialized economy. In contrast, the Democratic-Republican Party, championed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, emphasized states' rights, agrarian interests, and a limited federal government, fearing centralized power as a threat to individual liberties. These competing visions, rooted in debates over the Constitution and the nation’s economic future, crystallized into the first enduring political parties, shaping American politics and setting the stage for the two-party system that continues to define the country’s political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | The formation of the first two political parties in the United States emerged from the debates over the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the role of the federal government. |

| Parties | Federalist Party and Democratic-Republican Party |

| Founding Figures | Federalist Party: Alexander Hamilton, John Adams Democratic-Republican Party: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison |

| Time Period | Late 1780s to early 1790s |

| Ideological Divide | Federalists: Strong central government, support for industrialization, and close ties with Britain. Democratic-Republicans: States' rights, agrarian economy, and sympathy for France. |

| Key Issues | Ratification of the Constitution, national bank, taxation, and foreign policy. |

| Geographic Support | Federalists: Urban centers, New England Democratic-Republicans: Southern and rural areas |

| First Presidents | Federalist: John Adams (2nd President) Democratic-Republican: Thomas Jefferson (3rd President) |

| Decline | Federalist Party: Disbanded after the War of 1812 and the Hartford Convention. Democratic-Republican Party: Split into the Democratic Party and the Whig Party in the 1820s. |

| Legacy | Established the two-party system in American politics, shaping future political discourse and party dynamics. |

Explore related products

$84.95 $84.95

What You'll Learn

- Origins in Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist debates over Constitution ratification and central government power

- Hamilton’s Federalist Party advocating for strong central government and financial stability

- Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party promoting states’ rights and agrarian interests

- Role of the Whiskey Rebellion in polarizing political factions and party formation

- Influence of Washington’s farewell address warning against partisan divisions and foreign entanglements

Origins in Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist debates over Constitution ratification and central government power

The first two political parties in the United States emerged from the intense debates surrounding the ratification of the Constitution, a period marked by the clash between Federalists and Anti-Federalists. These factions, though not yet formal parties, laid the groundwork for the future of American politics by articulating opposing visions of governance. At the heart of their disagreement was the question of central government power: how much authority should the federal government wield, and at what cost to state sovereignty?

The Federalist Argument: A Stronger Union

Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, championed the Constitution as a necessary framework for a stable and effective national government. They argued that the Articles of Confederation had left the nation weak and divided, incapable of addressing economic crises or external threats. The Federalist vision emphasized a robust central authority with the power to regulate commerce, levy taxes, and maintain a standing army. Their case was persuasively made in the *Federalist Papers*, a series of essays that dissected the Constitution’s merits and addressed Anti-Federalist concerns. For Federalists, a stronger union was not just desirable but essential for the young nation’s survival.

The Anti-Federalist Counterpoint: Safeguarding Liberty

Anti-Federalists, including Patrick Henry and George Mason, viewed the Constitution with deep skepticism. They feared that a powerful central government would encroach on individual liberties and undermine the authority of the states. To them, the Constitution’s lack of a Bill of Rights was a glaring omission, leaving citizens vulnerable to potential tyranny. Anti-Federalists favored a more decentralized system, where states retained significant autonomy. Their warnings about federal overreach resonated with rural populations and those wary of distant, elite-dominated governance. While they ultimately lost the ratification battle, their insistence on protections for individual rights led to the swift adoption of the Bill of Rights.

The Birth of Political Parties

The Federalist-Anti-Federalist divide did not immediately translate into formal political parties, but it set the stage for their emergence. Federalists, who dominated the early federal government, coalesced into the Federalist Party, advocating for a strong executive and a national bank. Anti-Federalist sentiments, meanwhile, evolved into the Democratic-Republican Party under Thomas Jefferson, which championed states’ rights and agrarian interests. These parties were not mere extensions of the ratification debate but represented broader ideological and regional divides. The Federalists’ urban, commercial focus contrasted sharply with the Democratic-Republicans’ agrarian, decentralized vision.

Legacy and Lessons

The Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist debates highlight a fundamental tension in American politics: the balance between central authority and individual liberty. This tension persists today, shaping debates over federal power, states’ rights, and constitutional interpretation. Understanding these origins offers a lens through which to analyze modern political divisions. For instance, contemporary arguments about federal intervention in healthcare or education echo the Federalist-Anti-Federalist clash. By studying this history, we gain insight into the enduring principles and compromises that define American governance.

In practical terms, this history reminds us that political parties are not static entities but evolve in response to ideological and societal shifts. For educators, policymakers, or engaged citizens, tracing these origins can deepen appreciation for the complexities of the U.S. political system. It also underscores the importance of dialogue and compromise in resolving competing visions of governance—a lesson as relevant today as it was in the late 18th century.

Harris County Ballot: Are Political Party Affiliations Listed for Voters?

You may want to see also

Hamilton’s Federalist Party advocating for strong central government and financial stability

The Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, emerged in the 1790s as a response to the challenges of governing the fledgling United States. At its core, the party advocated for a strong central government, believing it essential for the nation’s survival and prosperity. Hamilton’s vision was rooted in his experiences during the Revolutionary War and his role as the first Secretary of the Treasury. He argued that a robust federal authority was necessary to address economic instability, defend against external threats, and prevent the fragmentation of the young republic. This stance set the Federalists apart from their rivals, the Democratic-Republicans, who favored states’ rights and a more limited federal role.

To achieve financial stability, Hamilton proposed a series of bold measures that remain foundational to American economic policy. First, he advocated for the assumption of state debts by the federal government, a move that solidified national credit and fostered investor confidence. Second, he established the First Bank of the United States, which provided a stable financial institution to manage the nation’s monetary affairs. Third, Hamilton introduced tariffs and excise taxes to generate revenue, ensuring the government could meet its obligations. These policies were not without controversy, but they laid the groundwork for a modern financial system. For instance, the national debt assumption alone reduced borrowing costs by 20%, demonstrating the immediate practical benefits of Hamilton’s approach.

The Federalists’ emphasis on a strong central government extended beyond economics. They believed in a powerful executive branch, as exemplified by George Washington’s presidency, and supported a standing army and navy to protect national interests. Hamilton’s *Federalist Papers*, particularly No. 23, argued that a unified defense policy was crucial for safeguarding the nation against foreign aggression. This perspective contrasted sharply with the Democratic-Republicans’ skepticism of centralized power, which they feared could lead to tyranny. The Federalists’ commitment to federal authority was further evident in their support for the Alien and Sedition Acts, though these measures later became a source of criticism for their perceived infringement on civil liberties.

Practically, the Federalist Party’s advocacy for financial stability and central authority had long-term implications for governance. Their policies created a framework for economic growth, enabling the United States to transition from a collection of agrarian states to an industrializing nation. However, their elitist reputation and urban focus alienated rural voters, contributing to their decline by the early 1800s. For modern readers, the Federalist legacy offers a lesson in balancing centralized power with democratic accountability. Policymakers today can draw on Hamilton’s principles when designing fiscal policies, such as debt management or banking regulation, while remaining mindful of the need for inclusivity and public trust.

In conclusion, the Federalist Party’s advocacy for a strong central government and financial stability was both visionary and contentious. Hamilton’s policies addressed immediate economic challenges while establishing enduring institutions. While their approach ultimately fell out of favor, it remains a critical chapter in American political history, offering insights into the trade-offs between federal authority and states’ rights. By studying the Federalists, we gain a deeper understanding of the foundations of U.S. governance and the ongoing debate over the role of central power in a democratic society.

The Independent Leader: America's Only Non-Partisan President Revealed

You may want to see also

Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party promoting states’ rights and agrarian interests

The formation of the first two political parties in the United States emerged from deep ideological divisions over the role of government, economic priorities, and the interpretation of the Constitution. Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party, born in the 1790s, championed states’ rights and agrarian interests as a counter to the Federalist Party’s vision of a strong central government and industrialized economy. This party’s platform was not merely a political stance but a reflection of the societal and economic realities of early America, where agriculture dominated and local autonomy was fiercely guarded.

Consider the agrarian focus of Jefferson’s party as a strategic response to the needs of the majority. In the late 18th century, over 90% of Americans lived in rural areas, relying on farming for sustenance and income. The Democratic-Republicans advocated for policies favoring this demographic, such as lower tariffs, reduced federal intervention, and land expansion through initiatives like the Louisiana Purchase. By prioritizing agriculture, Jefferson’s party positioned itself as the defender of the common man against what they saw as Federalist elitism and urban bias.

States’ rights were another cornerstone of the Democratic-Republican ideology, rooted in a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Jefferson and his allies argued that powers not explicitly granted to the federal government belonged to the states or the people. This principle was a direct challenge to Federalist policies like the national bank and Hamilton’s economic programs, which they viewed as overreaching. For instance, the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798–1799, authored by Jefferson and James Madison, asserted the right of states to nullify federal laws deemed unconstitutional—a bold statement of their commitment to decentralized power.

To understand the practical implications, imagine a farmer in early 19th-century Virginia. Under Federalist policies, he might face higher taxes, restrictive trade regulations, and a government more attuned to the needs of northeastern merchants. The Democratic-Republican Party promised relief: lower taxes, fewer federal mandates, and a government that respected his state’s authority. This appeal to local control and agrarian interests was not just ideological but deeply pragmatic, resonating with a population wary of distant, centralized authority.

In conclusion, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party was a product of its time, shaped by the agrarian economy and a suspicion of centralized power. By promoting states’ rights and agrarian interests, it offered a clear alternative to Federalist policies, laying the groundwork for enduring political divisions in American history. This focus on local autonomy and rural priorities remains a defining feature of the party’s legacy, illustrating how early political formations were inextricably tied to the social and economic fabric of the nation.

Partisanship's Grip: How Political Parties Fuel Division and Loyalty

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of the Whiskey Rebellion in polarizing political factions and party formation

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 was a pivotal event in early American history, serving as a catalyst for the polarization of political factions and the eventual formation of the first two political parties. At its core, the rebellion was a protest against the federal government’s excise tax on distilled spirits, but its implications extended far beyond taxation. It exposed deep ideological divides between those who favored a strong central government and those who championed states’ rights and local autonomy. These divisions laid the groundwork for the emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, shaping the nation’s political landscape for decades.

Consider the immediate context: the federal government, under President George Washington, imposed the whiskey tax to fund national debt and assert its authority. For farmers in western Pennsylvania, who relied on whiskey as a form of currency and a means to transport their surplus grain, the tax was an economic burden and a symbol of federal overreach. The rebellion began as localized resistance but quickly escalated into an armed insurrection, forcing Washington to raise a militia to enforce the law. This response highlighted the Federalists’ commitment to a robust central government capable of maintaining order, while anti-Federalists viewed it as an abuse of power and a threat to individual liberties.

Analyzing the aftermath reveals how the rebellion deepened political fault lines. Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, saw the rebellion as proof of the necessity for a strong federal authority to ensure stability and enforce laws uniformly. In contrast, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who would later form the Democratic-Republican Party, sympathized with the rebels’ grievances and argued that the federal government was overstepping its constitutional bounds. This ideological clash crystallized the differences between the two emerging parties: Federalists advocated for a centralized, commercial-oriented nation, while Democratic-Republicans championed agrarian interests and decentralized governance.

A practical takeaway from this episode is the role of economic policies in shaping political identities. The whiskey tax was not merely a fiscal measure but a litmus test for competing visions of America’s future. For instance, farmers in the frontier regions, who constituted a significant portion of the population, felt alienated by policies they perceived as favoring eastern elites. This alienation fueled their alignment with the Democratic-Republicans, who promised to protect their interests. Conversely, merchants and urban dwellers, who benefited from federal stability, gravitated toward the Federalists. Thus, the rebellion accelerated the coalescing of these groups into distinct political parties.

In conclusion, the Whiskey Rebellion was more than a tax protest; it was a defining moment in the formation of America’s first political parties. By exposing irreconcilable differences over the role of the federal government, it forced citizens to choose sides, solidifying the Federalist and Democratic-Republican factions. This polarization was not just ideological but also rooted in economic and regional realities, making the rebellion a critical case study in how policy disputes can reshape political landscapes. Understanding this event offers insight into the enduring tensions between central authority and local autonomy that continue to define American politics.

Unpacking Racial Identities: Which Political Party is Perceived as White?

You may want to see also

Influence of Washington’s farewell address warning against partisan divisions and foreign entanglements

The formation of the first two political parties in the United States, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, was deeply influenced by George Washington’s Farewell Address. Delivered in 1796, this document warned against the dangers of partisan divisions and foreign entanglements, yet its very existence catalyzed the ideological splits it sought to prevent. Washington’s cautionary words became a litmus test for emerging political factions, each interpreting his advice through the lens of their own ambitions and fears.

Washington’s warning against partisan divisions was rooted in his belief that political factions would undermine national unity and stability. He argued that parties were "potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people." Despite this, his address inadvertently highlighted the irreconcilable differences between Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists, who favored a strong central government and close ties with Britain, and Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans, who championed states’ rights and alignment with France. The Federalists viewed Washington’s words as a call to consolidate federal authority, while the Democratic-Republicans saw them as a defense of agrarian democracy against elitism.

The second pillar of Washington’s address—his caution against foreign entanglements—further polarized these emerging parties. He urged the nation to avoid "permanent alliances," advocating instead for neutrality and self-reliance. The Federalists, however, supported commercial and diplomatic ties with Britain, believing such relationships were essential for economic growth. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, inspired by the French Revolution, favored solidarity with France, even at the risk of alienating other powers. Washington’s warning thus became a battleground, with each party accusing the other of violating his principles.

Ironically, Washington’s address, intended to unify, became a blueprint for division. His warnings were not prescriptive policies but broad principles, leaving room for interpretation. The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans weaponized his words to legitimize their agendas, proving that even the most well-intentioned advice can be co-opted by competing interests. This dynamic underscores a critical lesson: warnings against division often reveal the fault lines they aim to conceal.

In practical terms, Washington’s Farewell Address serves as a cautionary tale for modern political discourse. It demonstrates how lofty ideals can be distorted to serve partisan ends. To avoid this, leaders must pair broad principles with specific, actionable guidelines. For instance, instead of merely warning against foreign entanglements, policymakers could establish clear criteria for alliances, such as mutual defense pacts limited to democratic nations or trade agreements with enforceable labor and environmental standards. Similarly, to mitigate partisan divisions, institutions could implement structural reforms, like ranked-choice voting or nonpartisan redistricting, to incentivize cooperation over polarization. Washington’s address remains relevant not as a solution but as a mirror, reflecting the challenges of balancing unity with diversity in a pluralistic society.

Ricky Polston's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first two political parties in the United States were the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party.

The formation of the first two political parties was primarily driven by differing views on the role of the federal government, the interpretation of the Constitution, and economic policies, particularly during the presidency of George Washington.

The Federalist Party was led by figures such as Alexander Hamilton, who advocated for a strong central government and industrial development, while the Democratic-Republican Party was led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who emphasized states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government.