The first organized political party in the United States emerged during the early years of the nation’s independence, as leaders began to coalesce around differing visions for the country’s future. The Federalist Party, founded in the early 1790s by Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and other proponents of a strong central government, is widely recognized as the first formal political party in American history. Advocating for policies such as a national bank, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, the Federalists sought to stabilize the young nation and promote economic growth. Their formation marked the beginning of partisan politics in the U.S., setting the stage for the development of the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, which championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government. This early party system laid the foundation for the enduring two-party dynamic that continues to shape American politics today.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Federalist Party |

| Founded | 1789-1791 (exact date debated) |

| Founding Leaders | Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, John Jay |

| Ideology | Federalism, strong central government, pro-business, pro-Bank of the United States |

| Base of Support | Merchants, bankers, urban professionals, New England |

| Key Achievements | Ratification of the Constitution, establishment of the First Bank of the United States, Jay Treaty |

| Notable Opponents | Democratic-Republican Party (led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison) |

| Decline | Early 1800s, after the War of 1812 and the rise of the Democratic-Republicans |

| Dissolution | 1820s |

| Legacy | Laid the groundwork for the American two-party system, shaped early American political discourse |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Democratic-Republican Party Formation

The Democratic-Republican Party, formed in the late 18th century, emerged as a direct response to the Federalist Party’s centralized policies and the perceived threat to individual liberties. Led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, this party championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Its formation marked the beginning of the first party system in the United States, setting the stage for organized political opposition and democratic debate.

To understand the party’s creation, consider the ideological clash between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. While Federalists favored a strong central government, national banking, and industrialization, Democratic-Republicans advocated for decentralized power, agrarian economy, and limited federal intervention. This divide was not merely philosophical; it had practical implications for governance, taxation, and the role of the common citizen. For instance, the Democratic-Republicans opposed the Federalist-backed Jay Treaty with Britain, arguing it compromised American sovereignty.

The party’s formation was a strategic move to counter Federalist dominance. Jefferson and Madison, initially part of George Washington’s administration, grew disillusioned with Federalist policies like the Alien and Sedition Acts, which restricted civil liberties. They mobilized supporters through newspapers, public meetings, and legislative alliances, leveraging grassroots support to challenge Federalist control. By 1800, their efforts culminated in Jefferson’s election as president, a victory that demonstrated the power of organized political opposition.

A key takeaway from the Democratic-Republican Party’s formation is its role in shaping American political culture. It introduced the concept of a loyal opposition, where competing parties could peacefully transition power. This model remains a cornerstone of U.S. democracy. Practical lessons include the importance of clear ideological stances, effective communication strategies, and coalition-building in political organizing. For modern activists, studying this era offers insights into mobilizing diverse groups toward a common goal.

Finally, the Democratic-Republican Party’s legacy extends beyond its time. Its emphasis on states’ rights and limited government influenced later movements, including the modern Republican Party. However, its agrarian focus became less relevant as the nation industrialized. Today, while the party no longer exists, its principles continue to resonate in debates over federalism, individual freedoms, and the balance of power. Understanding its formation provides a historical lens to navigate contemporary political challenges.

Political Parties: Uniting Government Branches or Dividing Their Efforts?

You may want to see also

Federalist Party Origins

The Federalist Party, emerging in the early 1790s, stands as the first organized political party in the United States, born from the contentious debates over the ratification of the Constitution. Its origins trace back to the leadership of Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, who championed a strong central government and a robust financial system. Hamilton’s vision, outlined in his economic policies, including the establishment of a national bank and the assumption of state debts, became the ideological cornerstone of the Federalists. This party coalesced around the belief that a centralized authority was essential for the young nation’s stability and prosperity, setting the stage for America’s first partisan divide.

To understand the Federalist Party’s formation, consider the steps that led to its creation. First, the ratification debates of 1787–1788 divided Americans into Federalists, who supported the Constitution, and Anti-Federalists, who feared centralized power. Second, Hamilton’s economic programs, particularly his 1790 *Report on Public Credit*, polarized Congress and the public. Third, the party formalized its structure through newspapers like *The Gazette of the United States*, which disseminated Federalist ideas and rallied supporters. These steps illustrate how ideological and practical concerns converged to create the nation’s first political party.

A comparative analysis highlights the Federalists’ unique position in early American politics. Unlike the Anti-Federalists, who favored states’ rights and agrarian interests, the Federalists prioritized industrialization, commerce, and a strong federal government. This distinction was not merely philosophical but had tangible implications: Federalists advocated for tariffs to protect domestic industries, while their opponents resisted measures seen as burdensome to farmers. The party’s urban, merchant-class base further differentiated it from the more rural Anti-Federalists, underscoring the socioeconomic fault lines of early American politics.

Practically speaking, the Federalist Party’s origins offer a cautionary tale about the challenges of governing a diverse nation. Their emphasis on central authority alienated many, particularly in the South, where states’ rights sentiment ran strong. For instance, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, former allies in the fight for independence, became staunch opponents of Federalist policies, eventually forming the Democratic-Republican Party. This opposition highlights the difficulty of balancing unity with regional interests—a lesson relevant to modern political organizers. When building a party, consider not only your core principles but also how they resonate across different constituencies.

In conclusion, the Federalist Party’s origins reveal the transformative power of ideas in shaping political movements. From Hamilton’s economic vision to the strategic use of media, the Federalists pioneered tactics still employed in American politics today. Their rise underscores the importance of clear ideology, effective communication, and adaptability in organizing a political party. While their dominance was short-lived, their legacy endures in the structure and dynamics of the two-party system. For anyone studying or engaging in politics, the Federalist Party’s story is a masterclass in the interplay of ideas, interests, and institution-building.

Key Traits of Political Parties: Identifying Their Defining Characteristics

You may want to see also

Key Founders: Jefferson & Madison

The Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, dominated early American politics, but it was the opposition to Federalist policies that sparked the formation of the first organized political party in the United States. This opposition coalesced around two towering figures: Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Their collaboration not only challenged Federalist dominance but also laid the groundwork for the Democratic-Republican Party, which would become a cornerstone of American political history.

The Ideological Spark: Jefferson’s Vision

Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, brought a distinct ideological framework to the nascent party. He championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Jefferson viewed the Federalist emphasis on centralized power and industrial growth as a threat to individual liberty and republican virtues. His 1798 Kentucky Resolutions, co-authored with Madison, articulated the principle of nullification, arguing that states could resist federal overreach. This philosophy became a rallying cry for those who feared the Federalists’ expansive vision of government.

Madison’s Strategic Genius

While Jefferson provided the ideological foundation, James Madison supplied the strategic and organizational acumen. As a key framer of the Constitution and author of the Bill of Rights, Madison understood the mechanics of political power. He recognized that opposition to the Federalists required more than just ideas—it needed structure. Madison’s efforts in Congress, particularly his role in exposing the flaws of Federalist policies like the Alien and Sedition Acts, galvanized public sentiment. His ability to build coalitions and mobilize supporters transformed Jefferson’s vision into a viable political movement.

A Partnership Forged in Opposition

The collaboration between Jefferson and Madison was rooted in their shared opposition to Federalist policies, but it also reflected their complementary strengths. Jefferson’s charisma and broad appeal made him the face of the movement, while Madison’s tactical brilliance ensured its organizational success. Their correspondence during the 1790s, particularly their discussions on the dangers of centralized power, reveals a partnership driven by both principle and pragmatism. Together, they crafted a platform that resonated with a diverse coalition of farmers, planters, and western settlers who felt marginalized by Federalist policies.

Legacy and Takeaway

The Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Jefferson and Madison, not only ended Federalist dominance but also established a template for two-party politics in the United States. Their emphasis on states’ rights, limited government, and individual liberty continues to influence American political thought. For modern political organizers, the Jefferson-Madison partnership offers a lesson in the power of combining ideological clarity with strategic organization. By focusing on shared principles and leveraging complementary strengths, they created a movement that reshaped the nation’s political landscape.

Unions and Politics: Which Party Truly Champions Workers' Rights?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

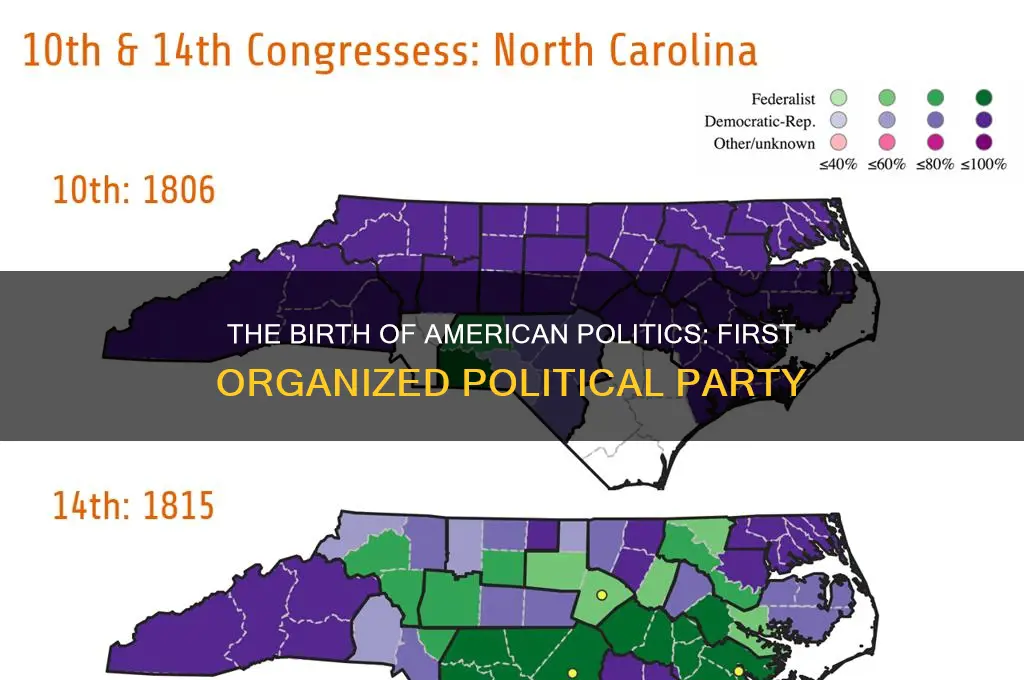

1790s Political Divide

The 1790s marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as the young nation’s leaders grappled with the question of how to govern a sprawling, diverse republic. This decade saw the emergence of the first organized political parties, a development that crystallized the ideological divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. At the heart of this split were competing visions of the nation’s future: centralized authority versus states’ rights, industrial growth versus agrarian stability, and alignment with Britain versus revolutionary France. This divide was not merely a policy disagreement but a fundamental clash over the identity and direction of the United States.

Consider the Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. They championed a strong central government, believing it essential for economic stability and national unity. Hamilton’s financial plans, including the establishment of a national bank and the assumption of state debts, were designed to consolidate federal power and foster industrial development. Federalists also favored close ties with Britain, viewing it as a stabilizing force in a turbulent world. Their vision was one of order, hierarchy, and modernization, often appealing to urban merchants and elites.

In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, advocated for a more decentralized government, emphasizing states’ rights and the preservation of agrarian society. They saw Hamilton’s policies as a threat to individual liberty and feared the rise of an American aristocracy. Jeffersonians idealized the yeoman farmer as the backbone of the nation and were sympathetic to the French Revolution’s ideals of equality and popular sovereignty. Their skepticism of centralized power and distrust of Britain set them apart from the Federalists, creating a sharp ideological rift.

This divide was not confined to policy debates; it permeated public discourse, media, and even personal relationships. Newspapers became partisan tools, with Federalist papers like *The Gazette of the United States* and Democratic-Republican papers like the *National Gazette* trading barbs and shaping public opinion. The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, passed by the Federalist-controlled Congress, further inflamed tensions by criminalizing dissent and targeting Jeffersonian supporters. This period laid the groundwork for the two-party system, but it also revealed the fragility of unity in a nation still defining itself.

Practical takeaways from this era remain relevant today. The 1790s political divide underscores the importance of balancing central authority with local autonomy, a tension that continues to shape American governance. It also highlights the dangers of partisan polarization, as ideological differences can quickly escalate into bitter conflicts. For modern policymakers and citizens, understanding this history offers a cautionary tale: while political parties can organize and mobilize public opinion, they must also strive to bridge divides rather than deepen them. The 1790s remind us that the health of a democracy depends on its ability to navigate competing visions without losing sight of shared national goals.

The Birth of American Politics: Founders of the First Political Party

You may want to see also

First Party System Era

The First Party System Era, spanning roughly from 1792 to 1824, marked the emergence of organized political parties in the United States, a development that reshaped the nation’s governance. At its core were the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, whose rivalry defined early American politics. The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, championed a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, advocated for states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal role. This period laid the groundwork for the two-party system, a structure that remains central to American democracy today.

To understand the dynamics of this era, consider the key issues that divided the parties. Federalists pushed for policies like the National Bank and protective tariffs, which they believed would stabilize the economy and foster national unity. Democratic-Republicans, however, saw these measures as favoring the elite and undermining individual liberty. The debate over the Jay Treaty of 1794, which resolved lingering issues with Britain but alienated France, further polarized the parties. These conflicts were not merely ideological; they reflected competing visions of America’s future—one urban and industrial, the other rural and agrarian.

A practical takeaway from this era is the importance of political organization in shaping policy outcomes. The Federalists’ ability to pass their agenda during George Washington’s and John Adams’ presidencies demonstrated the power of a unified party structure. Conversely, the Democratic-Republicans’ rise to dominance under Jefferson highlighted the effectiveness of grassroots mobilization and appeals to popular sovereignty. For modern political organizers, this period offers a lesson in the value of clear messaging and coalition-building, as both parties successfully rallied diverse constituencies around their core principles.

Comparatively, the First Party System Era stands in stark contrast to the earlier, more informal political alignments of the 1780s. Before this period, factions like the Federalists and Anti-Federalists lacked formal party structures, relying instead on personal networks and ad hoc alliances. The emergence of organized parties introduced discipline and consistency to political competition, though it also heightened polarization. This shift underscores the double-edged nature of party politics: while it provides a framework for coherent governance, it can also deepen ideological divides.

In analyzing the legacy of the First Party System, it’s crucial to note its role in democratizing American politics. The Democratic-Republicans’ emphasis on expanding suffrage and reducing property qualifications for voting laid the foundation for broader political participation. However, this democratization was limited, excluding women, enslaved Africans, and many free Black Americans. For historians and political scientists, this era serves as a reminder that the expansion of democracy is often incremental and uneven, shaped by the compromises and conflicts of its time. By studying this period, we gain insight into the enduring tensions between elite and popular interests in American politics.

Katherine Clark's Political Affiliation: Unveiling Her Party Membership

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first organized political party in the United States was the Federalist Party, founded in the early 1790s by Alexander Hamilton and other supporters of the Constitution.

The key figures behind the formation of the first political party, the Federalist Party, included Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and other proponents of a strong central government and the Constitution.

The Federalist Party aimed to promote a strong federal government, support the Constitution, encourage industrialization, and foster close ties with Britain, reflecting their vision for the nation’s future.