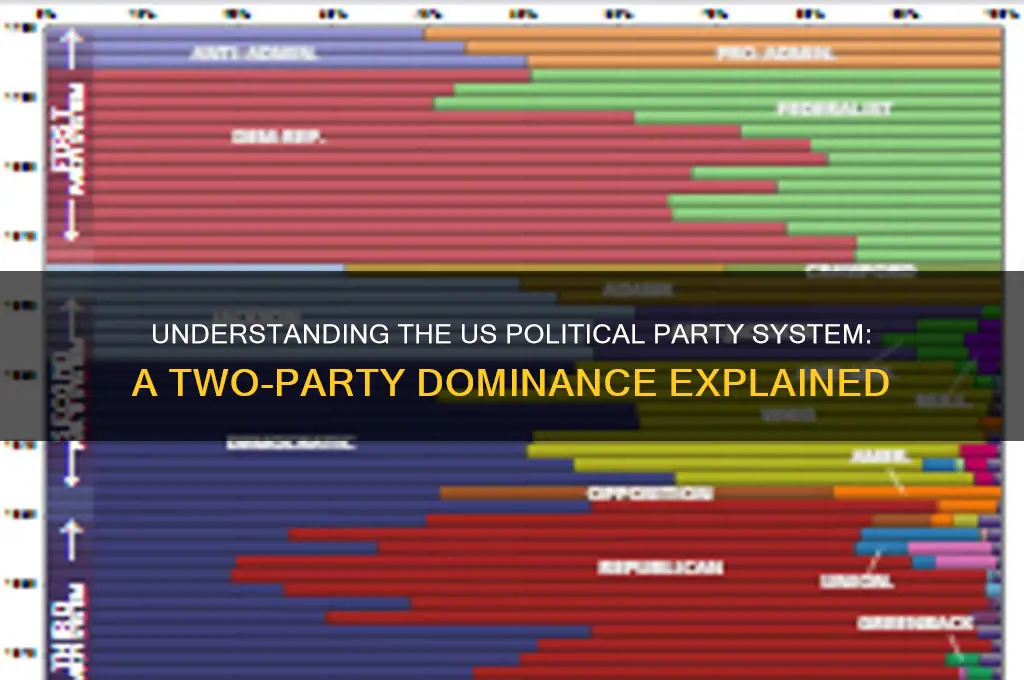

The United States operates under a two-party dominant system, where two major political parties—the Democratic Party and the Republican Party—have historically dominated electoral politics and governance. While the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly establish a two-party system, structural factors such as the winner-take-all electoral system, campaign financing laws, and historical precedents have solidified the dominance of these two parties. Smaller third parties, such as the Libertarian or Green Party, exist but face significant barriers to gaining widespread influence or winning national elections. This system contrasts with multi-party systems found in other democracies, where power is more evenly distributed among several parties. The two-party dynamic in the U.S. often leads to polarized politics, as the parties represent distinct ideological and policy positions, shaping the nation’s political discourse and governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Party System | Two-party dominant system |

| Major Political Parties | Democratic Party and Republican Party |

| Minor Parties | Exist but have limited influence (e.g., Libertarian, Green Party) |

| Electoral System | First-past-the-post (winner-takes-all) in most elections |

| Party Discipline | Relatively weak; members often vote independently |

| Ideological Spectrum | Democrats generally center-left, Republicans generally center-right |

| Role of Third Parties | Rarely win elections but can influence policy debates |

| Campaign Financing | Highly dependent on private donations and fundraising |

| Party Primaries | Closed or open primaries determine candidates for general elections |

| Federal vs. State Politics | Parties operate at both federal and state levels with varying strengths |

| Polarization | Increasing ideological divide between the two major parties |

| Voter Registration | Party affiliation required for primary voting in many states |

| Media Influence | Major parties dominate media coverage; minor parties often marginalized |

| Historical Stability | Two-party system has been dominant since the mid-19th century |

| Coalition Building | Less common due to the dominance of two major parties |

| Electoral College Role | Influences presidential elections, favoring the two-party system |

Explore related products

$11.95 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Two-Party Dominance: Republicans and Democrats dominate, marginalizing third parties despite their existence

- Pluralism vs. Elitism: Competing interests shape policy, but elites often hold disproportionate power

- Federalism’s Impact: State-level politics influence national party dynamics and policy priorities

- Electoral College Role: Shapes party strategies, focusing on swing states over popular vote

- Party Ideology Shifts: Evolving stances on issues reflect demographic and cultural changes over time

Two-Party Dominance: Republicans and Democrats dominate, marginalizing third parties despite their existence

The United States operates under a two-party system, where the Republican and Democratic parties dominate the political landscape, leaving little room for third parties to gain significant traction. This dynamic is not merely a coincidence but a structural outcome of the country's electoral system, which favors a winner-take-all approach in most elections. For instance, the Electoral College system in presidential elections and single-member districts in congressional races create high barriers for third parties to secure representation, as they must outperform one of the two major parties to win a seat.

Consider the practical implications of this dominance. Third parties, such as the Libertarian or Green Party, often struggle to secure ballot access in all 50 states, facing stringent signature requirements and filing fees. Even when they do appear on ballots, their candidates rarely receive more than a few percentage points of the vote. This marginalization is further reinforced by media coverage, which tends to focus on the horse-race dynamics between Republicans and Democrats, leaving third-party candidates with limited visibility. For example, during presidential debates, third-party candidates are frequently excluded unless they meet polling thresholds that are difficult to achieve without widespread media attention.

To understand why this two-party dominance persists, examine the psychological and strategic behaviors of voters. Many Americans engage in "strategic voting," casting their ballots for the lesser of two evils rather than supporting a third-party candidate they genuinely prefer. This phenomenon, known as Duverger's Law, predicts that plurality-rule elections in single-member districts will naturally lead to a two-party system. Voters fear "wasting" their vote on a candidate who cannot win, which perpetuates the cycle of Republican and Democratic dominance. For instance, in the 2000 presidential election, Ralph Nader's Green Party candidacy was blamed by some Democrats for siphoning votes from Al Gore, ultimately contributing to George W. Bush's victory.

Despite these challenges, third parties play a crucial role in shaping political discourse. They often introduce progressive or conservative ideas that are later adopted by the major parties. For example, the Progressive Party in the early 20th century pushed for reforms like women's suffrage and antitrust legislation, many of which were eventually embraced by Democrats and Republicans. Similarly, the Libertarian Party has influenced debates on issues like drug legalization and government spending. However, their impact remains indirect, as they rarely achieve direct representation in Congress or the presidency.

To break the cycle of two-party dominance, structural reforms could be considered. Implementing ranked-choice voting, where voters rank candidates in order of preference, could reduce the spoiler effect and encourage more third-party participation. Additionally, lowering ballot access barriers and providing public funding for third-party campaigns could level the playing field. While these changes would not guarantee third-party success, they would create a more inclusive and competitive political environment. Until such reforms are enacted, the U.S. political system will likely continue to be defined by the Republican-Democratic duopoly, with third parties relegated to the margins.

The Anti-Federalists' Push for the Bill of Rights Explained

You may want to see also

Pluralism vs. Elitism: Competing interests shape policy, but elites often hold disproportionate power

The United States operates within a two-party system, dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties, which has led to a complex interplay of pluralism and elitism in its political landscape. Pluralism suggests that power is distributed among various interest groups, each vying for influence in policy-making. In practice, this means labor unions, corporations, environmental organizations, and other stakeholders engage in a constant tug-of-war to shape legislation. For instance, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 was the result of negotiations between healthcare providers, insurance companies, and patient advocacy groups, demonstrating how competing interests can collaboratively—or contentiously—mold policy outcomes.

However, the reality often tilts toward elitism, where a small, wealthy, and well-connected group wields disproportionate power. Elites, including corporate executives, lobbyists, and political donors, have the resources to amplify their voices through campaign contributions, exclusive access to lawmakers, and sophisticated lobbying efforts. A 2014 study by Princeton and Northwestern universities found that policies aligned more closely with the preferences of economic elites and organized interest groups than with the desires of the average citizen. This imbalance is evident in areas like tax policy, where loopholes favoring the wealthy persist despite widespread public support for progressive taxation.

To illustrate, consider the influence of the National Rifle Association (NRA) versus grassroots gun control movements. Despite broad public backing for stricter gun laws, the NRA’s financial clout and targeted lobbying have consistently blocked significant federal legislation. Conversely, the #MeToo movement, a pluralistic effort, successfully pushed for policy changes in sexual harassment laws, showing that collective action can sometimes counter elite dominance. Yet, such victories are often the exception rather than the rule.

Balancing pluralism and elitism requires systemic reforms. Campaign finance reform, stricter lobbying regulations, and increased transparency in political donations could level the playing field. For instance, public financing of elections, as seen in some state-level campaigns, reduces reliance on wealthy donors. Additionally, empowering grassroots organizations through digital tools and community organizing can amplify underrepresented voices. While elites will always seek influence, fostering a more inclusive political process ensures that policy reflects the needs of all citizens, not just the privileged few.

Ultimately, the tension between pluralism and elitism is a defining feature of American politics. Recognizing this dynamic allows citizens to engage more strategically, whether by supporting reform efforts, participating in collective action, or holding elected officials accountable. The goal is not to eliminate elite influence but to ensure it does not overshadow the diverse interests of the broader population. In a healthy democracy, power should be a shared resource, not a monopoly.

Understanding Political Party Registration: What It Means and Why It Matters

You may want to see also

Federalism’s Impact: State-level politics influence national party dynamics and policy priorities

The United States operates under a two-party system, dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties, but this national framework is deeply intertwined with its federalist structure. Federalism ensures that state-level politics play a pivotal role in shaping national party dynamics and policy priorities. This interplay is not merely theoretical; it manifests in tangible ways, from campaign strategies to legislative agendas. For instance, issues like gun control, abortion, and education often emerge from state-level debates before becoming national priorities, reflecting the diverse political landscapes across the 50 states.

Consider the laboratory of democracy concept, where states act as testing grounds for policies that may later be adopted at the federal level. California’s aggressive climate change legislation, for example, has influenced Democratic Party platforms nationally, while Texas’s conservative policies on immigration and energy have shaped Republican priorities. This dynamic is further amplified by the Electoral College system, which forces national parties to tailor their messages to swing states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Arizona. As a result, state-level issues often dictate the terms of national discourse, with parties adapting their platforms to appeal to local constituencies.

However, this federalist influence is not without challenges. The decentralization of power can lead to policy fragmentation, where national cohesion is sacrificed for state-specific interests. For instance, while some states expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, others refuse, creating disparities in healthcare access. This patchwork approach complicates national party messaging, as Democrats and Republicans must balance their overarching ideologies with the diverse demands of their state-level bases. Parties must navigate this tension carefully, often adopting a one-size-fits-all approach that risks alienating certain voter blocs.

To effectively engage with this system, political strategists and policymakers must adopt a dual-level approach. First, they should monitor state-level trends to anticipate emerging issues that could gain national traction. Second, they must craft flexible platforms that resonate across diverse state contexts while maintaining a cohesive national identity. For example, Democrats might emphasize economic equality in Rust Belt states while focusing on environmental justice in the West. Republicans, meanwhile, could highlight fiscal conservatism in the South while addressing infrastructure needs in the Midwest.

Ultimately, federalism’s impact on national party dynamics underscores the importance of understanding state-level politics as a driving force in American governance. By recognizing how local issues shape national priorities, parties can better navigate the complexities of the two-party system and address the needs of a diverse electorate. This interplay between federal and state politics is not just a feature of the U.S. system—it is its defining characteristic, shaping everything from campaign strategies to policy outcomes.

KKK's Political Ties: Uncovering the Party's Disturbing Historical Connections

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Electoral College Role: Shapes party strategies, focusing on swing states over popular vote

The United States operates under a two-party system, dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties, a structure deeply influenced by the Electoral College. This mechanism, established by the Constitution, does not directly elect the president via the popular vote but through electors allocated by state. Each state’s electoral votes, equal to its congressional representation, create a winner-take-all system in all but two states (Maine and Nebraska). This design forces candidates to prioritize swing states—battlegrounds like Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—where outcomes are unpredictable, over safely red or blue states, regardless of population size.

Consider the 2020 election: Joe Biden and Donald Trump campaigned heavily in Arizona, Michigan, and Georgia, states with a combined 41 electoral votes, while largely ignoring California’s 55 or Texas’s 38, despite their larger populations. This strategy reflects the Electoral College’s distortion of campaign focus. Candidates allocate resources disproportionately to swing states, tailoring messages to local issues like auto manufacturing in Michigan or immigration in Arizona. Meanwhile, national issues affecting densely populated states, such as housing affordability in California, receive less attention, as their electoral outcomes are virtually guaranteed.

This system has profound implications for policy and representation. Candidates craft platforms to appeal to swing state demographics, often sidelining broader national concerns. For instance, agricultural policy gains outsized attention due to Iowa’s early caucus status, while urban issues in New York or Illinois are neglected. This skews governance toward the interests of a few states, undermining the principle of "one person, one vote." Critics argue this undermines democracy, as the popular vote winner can lose the election (as in 2000 and 2016), while defenders claim it protects smaller states from being overshadowed by urban centers.

To navigate this system effectively, campaigns employ data-driven strategies, focusing on voter turnout in key counties within swing states. For example, in 2016, Trump’s narrow victories in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin hinged on mobilizing rural voters and suppressing urban turnout. Democrats, in contrast, prioritize suburban areas and minority communities in these states. This tactical approach reinforces the Electoral College’s role in shaping party strategies, as candidates optimize for electoral votes rather than the national popular will.

In conclusion, the Electoral College compels parties to adopt a state-by-state, rather than national, campaign strategy. This focus on swing states distorts resource allocation, policy priorities, and voter engagement, creating a system where the path to victory is paved through a handful of states rather than a broad national coalition. Whether this strengthens federalism or weakens democracy remains a contentious debate, but its impact on party strategies is undeniable.

Bill Gates' Political Stance: Philanthropy, Advocacy, and Global Influence Explained

You may want to see also

Party Ideology Shifts: Evolving stances on issues reflect demographic and cultural changes over time

The United States operates under a two-party system, dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties, which has shaped its political landscape for nearly two centuries. This structure often limits the representation of diverse ideologies, forcing parties to adapt and evolve to remain relevant. One of the most striking examples of this adaptability is how party ideologies shift in response to demographic and cultural changes. Consider the Democratic Party’s transformation from a conservative, segregationist force in the early 20th century to a progressive, multicultural coalition today. This evolution wasn’t accidental—it was driven by the Civil Rights Movement, immigration waves, and the rise of identity politics, which reshaped the party’s base and priorities.

To understand how these shifts occur, examine the mechanics of demographic change. As younger generations, who tend to hold more liberal views on issues like LGBTQ+ rights and climate change, replace older voters, parties must adjust their platforms to appeal to this new electorate. For instance, the Republican Party’s recent emphasis on economic populism and cultural conservatism reflects its attempt to retain its base amid declining support from suburban and college-educated voters. Conversely, the Democratic Party’s embrace of policies like student debt relief and universal healthcare mirrors the priorities of millennials and Gen Z, who now constitute a significant portion of the voting population.

However, these shifts are not without risks. Parties that move too quickly or too far risk alienating their traditional supporters. The Democratic Party’s leftward shift on issues like defunding the police, for example, has sparked internal divisions between progressives and moderates. Similarly, the Republican Party’s alignment with Trumpism has led to a rift between its populist base and its traditional conservative establishment. Balancing these competing demands requires strategic finesse, as parties must navigate the tension between appealing to new demographics and retaining their core constituencies.

Practical tips for understanding these shifts include tracking polling data on key issues, analyzing voter turnout patterns by age and ethnicity, and studying the rhetoric of party leaders. For instance, the increasing use of terms like “equity” and “sustainability” in Democratic speeches reflects the party’s focus on social justice and environmental concerns. Conversely, the Republican Party’s emphasis on “freedom” and “patriotism” underscores its appeal to cultural traditionalists. By monitoring these trends, observers can predict how parties will continue to evolve in response to America’s changing demographic and cultural landscape.

In conclusion, party ideology shifts are not random but are deeply rooted in the evolving demographics and cultural values of the United States. As the nation grows more diverse and younger generations come of age, both the Democratic and Republican parties will face pressure to adapt their stances on critical issues. While this adaptability is essential for survival in a two-party system, it also carries the risk of internal division and voter alienation. By staying attuned to these dynamics, voters and analysts alike can better understand the forces shaping American politics and anticipate future changes.

Antebellum Evolution: Shaping Political Parties in a Changing America

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The US has a two-party dominant system, where the Democratic Party and the Republican Party dominate politics at the federal and state levels.

Yes, there are smaller third parties, such as the Libertarian Party and the Green Party, but they rarely win major elections due to structural and electoral barriers.

The two-party system is largely a result of the "winner-take-all" electoral system, where the candidate with the most votes wins, discouraging the growth of smaller parties.

While theoretically possible, significant changes to electoral laws, such as implementing proportional representation, would be required to facilitate a transition to a multi-party system.