The Supreme Court of the United States is the country's highest judicial body, with one Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices. The Supreme Court's decisions have a profound impact on society, shaping history and influencing civil rights and liberties. Its power of judicial review ensures that each branch of government recognises its limits and that laws do not violate the Constitution. This includes landmark cases such as Brown v. Board of Education, which ended racial segregation in schools, and Miranda v. Arizona, which established the requirement for police to inform suspects of their rights before questioning. The Supreme Court also hears cases on a wide range of issues, from students' rights to abortion and affirmative action, shaping the legal landscape of the nation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | May 17, 1954 |

| Case Name | Brown v. Board of Education |

| Holding | Separate schools are not equal |

| Overturned | Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) |

| Landmark Status | Yes |

| Importance | Helped lay the ground for the civil rights movement and integration across the country |

| Issue | Constitutionality of segregation in public education |

| Decision | Segregation of children in public schools on the basis of race was unconstitutional |

| Majority Opinion Author | Earl Warren |

| Jurisdiction | Original jurisdiction |

| Court Composition | One Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices |

Explore related products

$7.99 $7.99

What You'll Learn

Students' free speech rights

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects the right to free speech, stating that "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech...". This right is also extended to students, albeit with certain limitations. The Supreme Court has played a significant role in defining the boundaries of students' free speech rights, particularly in public schools.

Tinker v. Des Moines (1969)

One of the most significant cases regarding students' free speech rights is Tinker v. Des Moines. In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the First Amendment rights of students, stating that they do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate". The case involved students who were suspended for wearing black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. The Court ruled that school officials may not punish or prohibit student speech unless it causes a substantial disruption to school activities or infringes on the rights of others. This case set a precedent for evaluating the constitutionality of restrictions on student speech in public schools.

Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986)

In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that public school officials can prohibit offensive student speech. The case involved a student, Matthew Fraser, who made a speech at a mandatory high school assembly with sexually suggestive double entendres. The Court held that Fraser's speech was offensive and "inconsistent with the 'fundamental values' of public school education".

Morse v. Frederick

The Court reviewed a high school's restriction on student speech in this case. A student displayed a banner reading "BONG HiTS 4 JESUS" at a school-sponsored event. The Court upheld the restriction, even though the banner did not cause substantial disruption, indicating that schools may restrict speech that promotes illegal drug use.

Bell v. Itawamba County School Board (2012)

In this case, the court ruled that school officials did not violate the First Amendment by punishing a student for posting a rap song online that criticized two football coaches. This case highlights the evolving landscape of student free speech in the digital age, with schools grappling with the question of their authority to regulate student speech on social media.

Other Notable Cases

- Healy v. James (1972): The Court affirmed college students' First Amendment rights of free speech and association.

- Norton v. Discipline Committee of East Tennessee State University (1970): Involved college students' First Amendment rights to distribute "inflammatory" pamphlets on campus.

- Beussink v. Woodland School District (1998): The First Amendment was used to protect a student's right to maintain a critical website about their school.

- Burnside v. Byars (1966): Protected students' First Amendment rights on school grounds, setting a precedent for Tinker v. Des Moines.

While these cases represent important milestones in upholding students' free speech rights, it is essential to recognize that the legal landscape is ever-evolving, particularly with the increasing influence of social media and digital communication. The ongoing struggle to balance free speech rights with the objectives of the public education system demonstrates the complexity of this issue.

The Secret to Best-Selling Book Status Revealed

You may want to see also

Random drug testing of students

One notable case is Vernonia School District v. Acton (1995), where the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a school district's policy of random drug testing for student athletes. The Court ruled that the policy did not violate the Fourth Amendment, considering the athletes' diminished expectation of privacy and the government's interest in promoting student safety and a drug-free environment. This case set a precedent for balancing students' privacy rights with the government's goal of drug deterrence.

In 2002, the Supreme Court extended its decision in Vernonia to a broader context in Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls. In this case, the Court upheld the constitutionality of randomly drug testing students who participated in competitive, non-athletic extracurricular activities. The Court found that such a policy was a reasonably effective means of addressing the school district's concerns in preventing and detecting drug use.

Lower courts have also weighed in on random drug testing of students. For example, in Joy v. Penn Harris Madison School Corporation (2000), the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a suspicionless drug testing program for student athletes, while acknowledging potential Fourth Amendment concerns. Additionally, state supreme courts in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Indiana have ruled on similar cases, with varying outcomes depending on state law and specific circumstances.

Overall, the legality of random drug testing of students depends on a complex interplay between students' constitutional rights, the government's interest in deterring drug use, and the specific circumstances of each case. While some courts have upheld random drug testing policies, others have found them to violate privacy protections guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment and state constitutions.

Swearing In: Bible Required?

You may want to see also

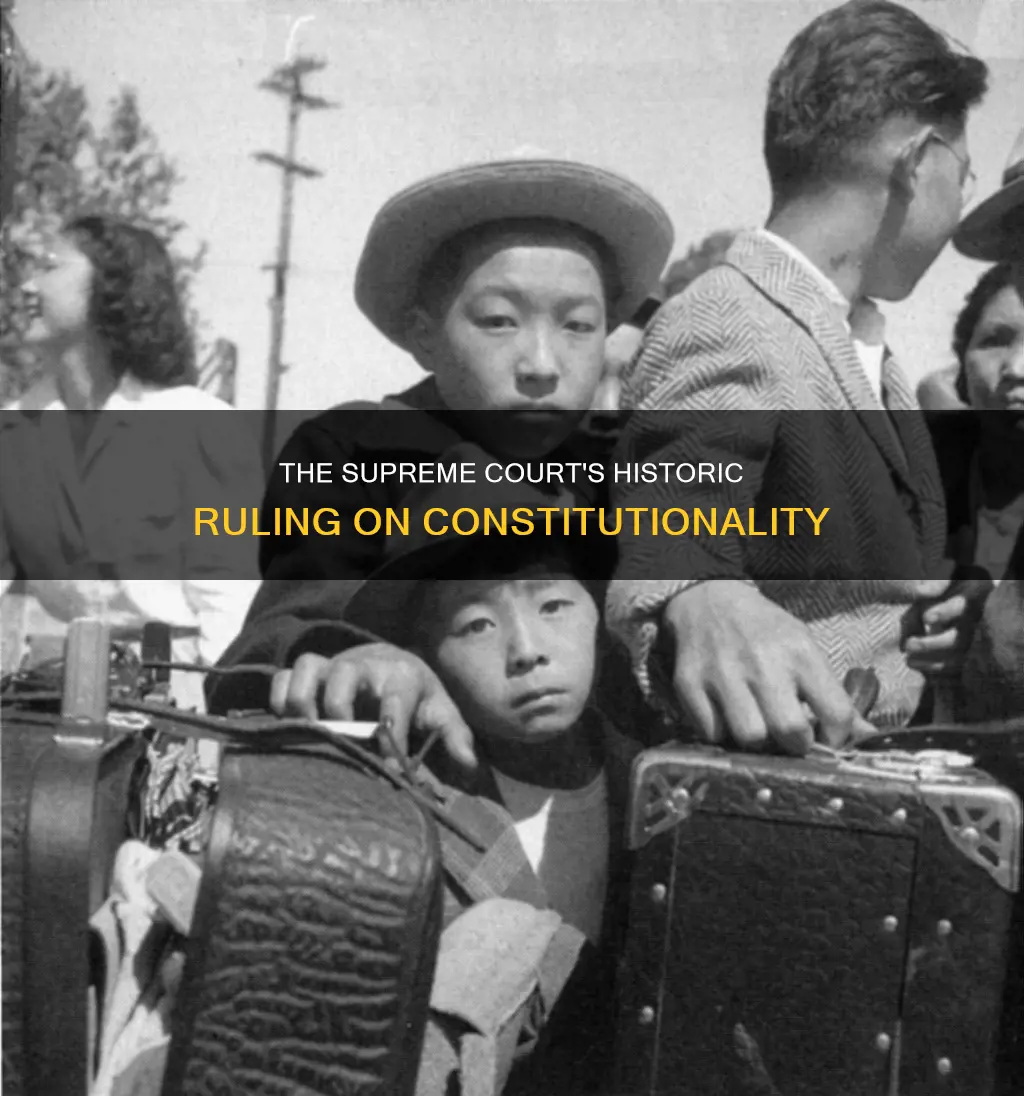

Racial segregation in schools

In the United States, racial segregation in schools was a dominant feature of race relations for much of the 60 years preceding the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954. Such state policies had been endorsed by the United States Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which held that as long as the separate facilities for different races were equal, state segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. This "separate but equal" doctrine was rejected by proponents of judicial activism, who believed the Supreme Court should adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times.

In 1951, a class-action lawsuit was filed against the Board of Education of the City of Topeka, Kansas, in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas. The plaintiffs were thirteen Topeka parents on behalf of their 20 children. The suit called for the school district to reverse its policy of racial segregation, which was based on an 1879 law that allowed for separate elementary schools for white and African-American students in communities with more than 15,000 residents. Each of the families attempted to enrol their children in the closest school, which were designated for whites, and were refused admission, being directed to the African-American schools, which were much further away.

The Topeka Board of Education's segregation policy was alleged to be unconstitutional, and the case was heard by a three-judge court of the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas, which ruled against the plaintiffs, relying on the precedent of Plessy v. Ferguson and its "separate but equal" doctrine. The plaintiffs, represented by NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, appealed the ruling directly to the Supreme Court.

In May 1954, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous 9-0 decision in favour of the plaintiffs, ruling that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal" and that laws imposing them violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This decision marked a reversal of the Court's earlier endorsement of "separate but equal" in Plessy v. Ferguson and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement. The Brown v. Board of Education case was a combination of five cases involving segregation at public schools in Kansas, Delaware, Virginia, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia.

Health Insurance: Joining Outside Open Enrollment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Suspects' rights to counsel

Ernesto Miranda, the defendant in this case, confessed to rape and kidnapping after hours of police interrogation. At his trial, Miranda sought to suppress his confession, arguing that he had not been advised of his rights to counsel and to remain silent. The Supreme Court agreed with Miranda, establishing that police must inform suspects of their rights before any questioning.

The Miranda ruling was based on the Sixth Amendment right to assistance of counsel and the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. The Court held that these rights apply to criminal state trials and that "lawyers in criminal court are necessities, not luxuries." This decision expanded public defender systems across the country.

Subsequent Supreme Court cases have further clarified suspects' rights to counsel. For example, in New York v. Quarles (1984), the Court ruled that roadside questioning during a routine traffic stop does not constitute "custodial interrogation" for Miranda purposes. In Oregon v. Bradshaw (1983), the Court held that police may continue questioning a suspect after they have invoked their right to counsel if the suspect initiates further conversation and waives their right. In Davis v. U.S. (1994), the Court clarified that law enforcement officers may continue questioning a suspect after they have waived their Miranda rights, unless the suspect explicitly requests an attorney.

The Massachusetts Constitution: Supporting Freedom and Democracy

You may want to see also

States' powers to regulate commerce

The Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, gives Congress the power to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes". The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has been a source of ongoing controversy regarding the balance of power between the federal government and the states.

Early Supreme Court cases, including Gibbons v. Ogden in 1824, primarily viewed the Commerce Clause as limiting state power, rather than as a source of federal power. In Gibbons, the Supreme Court held that intrastate activity could be regulated under the Commerce Clause. In United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co. (1942), the Court upheld federal price regulation of intrastate milk commerce, asserting that the commerce power extends to intrastate activities that affect interstate commerce.

In the 1930s, the Court began to recognise broader grounds upon which the Commerce Clause could be used to regulate state activity. In NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp (1937), the Supreme Court held that any activity with a “substantial economic effect” on interstate commerce could be regulated as commerce. From 1937 to 1995, the Supreme Court did not invalidate a single law on the basis of overstepping the Commerce Clause’s grant of power.

In United States v. Lopez (1995), the Supreme Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad legislative mandate under the Commerce Clause by returning to a more conservative interpretation of the clause. The Court confined its regulatory authority to intrastate economic activity. In Gonzales v. Raich (2005), a medical marijuana case, the Supreme Court rejected the argument that the ban on growing medical marijuana for personal use exceeded the powers of Congress under the Commerce Clause. The Court found that there could be an indirect effect on interstate commerce.

The Dormant Commerce Clause refers to the prohibition, implicit in the Commerce Clause, against states passing legislation that discriminates against or excessively burdens interstate commerce. For example, in West Lynn Creamery Inc. v. Healy, the Supreme Court struck down a Massachusetts state tax on milk products because the tax impeded interstate commercial activity by discriminating against non-Massachusetts citizens and businesses.

Due Diligence: Searching for the Decedent's Will

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Board of Education of Independent School District #92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls (2002).

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

Miranda v. Arizona (1966).