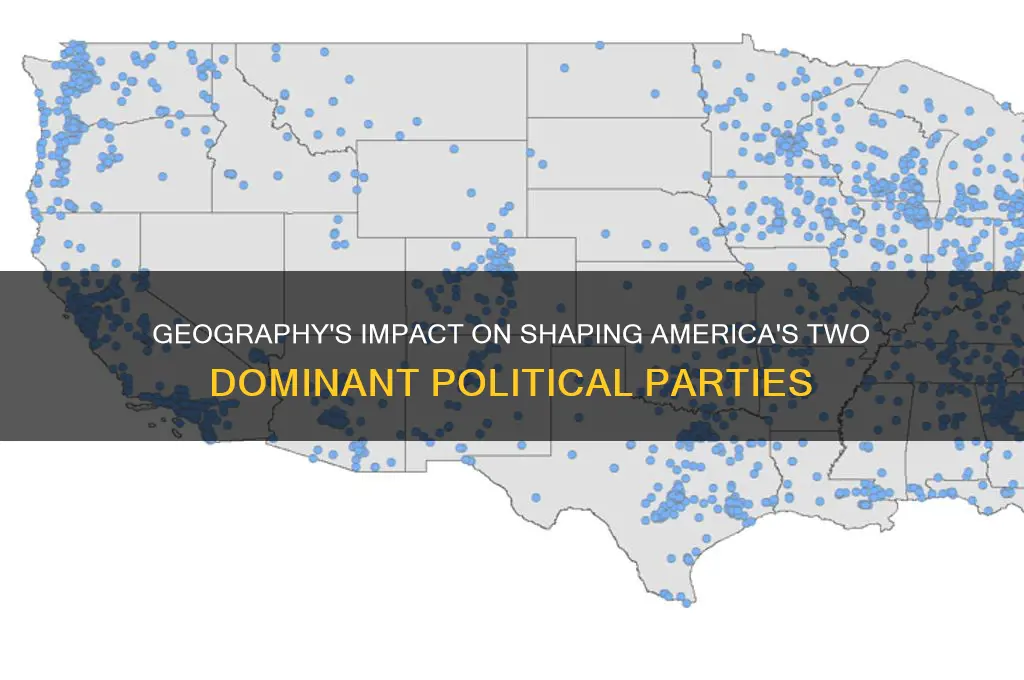

Geography has played a significant role in shaping the dynamics and ideologies of the two major political parties in the United States. The Democratic Party has traditionally found strong support in urban areas, coastal regions, and large metropolitan centers, where diverse populations and economic activities foster progressive policies focused on social welfare, environmental protection, and multiculturalism. In contrast, the Republican Party has historically drawn its base from rural areas, the South, and the Midwest, where agricultural interests, conservative values, and a focus on states' rights and limited government intervention resonate more strongly. This geographic divide reflects not only demographic and economic differences but also cultural and historical factors that continue to influence party platforms and voter preferences.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Regional Voting Patterns | Geography strongly influences voting behavior in the U.S. The Republican Party dominates rural and suburban areas, particularly in the South, Midwest, and parts of the West. The Democratic Party performs better in urban areas, coastal states, and large metropolitan regions. |

| Urban vs. Rural Divide | Urban areas tend to lean Democratic due to diverse populations, higher education levels, and emphasis on social services. Rural areas lean Republican, often prioritizing traditional values, gun rights, and local control. |

| Southern vs. Northern Politics | The South has historically been a stronghold for the Republican Party, influenced by cultural conservatism and economic policies. The North, especially the Northeast, tends to favor the Democratic Party, with a focus on progressive policies and social welfare. |

| State-Level Policies | Geographic location influences state-level policies, such as taxation, healthcare, and environmental regulations. Red states (Republican-leaning) often have lower taxes and fewer regulations, while blue states (Democratic-leaning) tend to have higher taxes and more progressive policies. |

| Electoral College Impact | Geography plays a critical role in the Electoral College, where swing states like Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin often determine presidential elections. These states' geographic and demographic characteristics make them battlegrounds for both parties. |

| Resource-Based Politics | Regions with specific industries (e.g., coal in Appalachia, oil in Texas) often align with the party that supports those industries. Republicans typically favor resource extraction, while Democrats push for environmental regulations and renewable energy. |

| Immigration and Border States | Border states like Texas, Arizona, and California have unique political dynamics due to immigration issues. Republicans often emphasize border security, while Democrats focus on immigrant rights and pathways to citizenship. |

| Cultural and Religious Influence | Geography shapes cultural and religious identities, which align with political parties. The Bible Belt in the South is strongly Republican, while more secular regions in the Northeast and West Coast lean Democratic. |

| Infrastructure and Development | Geographic needs influence infrastructure priorities. Rural areas often prioritize roads and agriculture, aligning with Republican policies, while urban areas focus on public transportation and housing, aligning with Democratic priorities. |

| Climate and Environmental Policies | Coastal states are more likely to support Democratic policies addressing climate change due to vulnerability to rising sea levels. Inland states may prioritize Republican policies that support traditional energy industries. |

Explore related products

$11.99 $19.99

$1.99 $18

What You'll Learn

Geographic influence on party formation

Geography has been a silent architect in the formation and evolution of political parties, shaping ideologies, alliances, and voter bases in profound ways. Consider the United States, where the Democratic Party’s strongholds are often urban centers like New York and Los Angeles, while the Republican Party dominates rural and suburban areas. This division isn’t arbitrary; it reflects geographic differences in economic interests, population density, and cultural values. Urban areas, with their diverse populations and reliance on service industries, tend to favor progressive policies, whereas rural regions, dependent on agriculture and natural resources, lean conservative. This geographic split isn’t unique to the U.S.—similar patterns emerge in countries like India, where regional parties thrive based on local issues tied to geography, such as water rights or land use.

To understand how geography influences party formation, examine the role of natural resources. In resource-rich regions, political parties often emerge to advocate for the exploitation or conservation of those resources. For instance, in Alberta, Canada, the Conservative Party’s dominance is tied to its support for the oil and gas industry, a cornerstone of the province’s economy. Conversely, in British Columbia, where environmental concerns are paramount, the Green Party and environmentally conscious factions of the New Democratic Party gain traction. This dynamic illustrates how geography doesn’t just shape party platforms but also determines which parties gain a foothold in specific regions. Practical tip: When analyzing party formation, always map the region’s primary industries and environmental challenges to predict political leanings.

A comparative analysis reveals that geography’s influence on party formation is particularly pronounced in federal systems. In Germany, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) has traditionally been strong in the west, while the Social Democratic Party (SPD) has roots in the industrial regions of the Ruhr Valley. Post-reunification, the former East Germany became a stronghold for the Left Party, reflecting lingering economic disparities tied to geography. Similarly, in Brazil, the Workers’ Party (PT) draws significant support from the industrialized southeast, while the agribusiness-friendly centrão coalition dominates the agricultural heartland. This pattern underscores how geographic divisions often mirror political ones, with parties forming or adapting to represent the unique needs of their regions.

Persuasively, one could argue that geography not only influences party formation but also perpetuates political polarization. When parties become geographically entrenched, they risk losing touch with voters outside their core areas, leading to policies that favor one region at the expense of another. For example, in the U.S., the urban-rural divide has deepened as parties increasingly cater to their geographic bases, exacerbating tensions over issues like gun control, healthcare, and infrastructure spending. To mitigate this, parties could adopt a more geographically inclusive approach, such as rotating national conventions across regions or prioritizing cross-regional alliances. Caution: Overemphasis on geographic representation can lead to neglect of national issues, so balance is key.

Finally, a descriptive lens reveals how geography’s influence on party formation is often intertwined with history and culture. In the American South, the Republican Party’s rise in the late 20th century was rooted in both geographic and cultural factors, as rural and suburban voters aligned with its conservative values. Similarly, in Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) gained momentum by leveraging geographic identity and historical grievances against centralization. This interplay of geography, history, and culture creates a fertile ground for party formation, as politicians tap into regional pride and local issues to build support. Takeaway: Geography isn’t just a backdrop for politics—it’s an active participant, shaping the very DNA of political parties.

Do Political Parties Control Redistricting? Power, Influence, and Gerrymandering Explained

You may want to see also

Urban vs. rural voter divides

Geography has long shaped political allegiances, and the urban-rural divide stands as one of the most pronounced fault lines in modern politics. Cities, with their dense populations and diverse demographics, tend to lean toward progressive policies, while rural areas, characterized by lower population density and homogenous communities, often favor conservative ideals. This split isn’t merely ideological; it’s rooted in the distinct economic, social, and cultural realities of these environments. Urban centers thrive on industries like technology and finance, fostering a worldview that values innovation and inclusivity. Rural regions, reliant on agriculture and manufacturing, often prioritize tradition and self-reliance. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for anyone seeking to navigate the complexities of contemporary political landscapes.

Consider the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where this divide was starkly evident. Urban counties, such as those encompassing New York City and Los Angeles, overwhelmingly supported the Democratic candidate, while rural counties across the Midwest and South leaned heavily Republican. This pattern isn’t unique to the U.S.; similar trends appear in countries like France and Brazil. In France, for instance, urban voters in Paris backed Emmanuel Macron’s centrist platform, while rural voters in regions like Burgundy favored Marine Le Pen’s nationalist agenda. These examples illustrate how geography doesn’t just influence voting behavior—it often dictates it. To bridge this gap, policymakers must address the specific needs of both urban and rural populations, from public transportation in cities to agricultural subsidies in the countryside.

The economic disparities between urban and rural areas further exacerbate this political divide. Urban voters, often benefiting from higher wages and access to services, are more likely to support progressive taxation and social welfare programs. Rural voters, facing declining industries and limited job opportunities, tend to view such policies as detrimental to their livelihoods. For instance, a study by the Pew Research Center found that 62% of rural Americans believe the economic system unfairly favors powerful interests, compared to 53% of urban residents. This perception fuels skepticism toward government intervention in rural areas, while urban voters see it as a necessary tool for equity. To mitigate this tension, initiatives like rural broadband expansion and urban job training programs could help align economic interests across geographies.

Cultural differences also play a significant role in this divide. Urban areas, with their multicultural populations, often embrace policies promoting diversity and social change. Rural communities, where traditions run deep, may view such changes as threats to their way of life. Take the issue of gun control: urban voters, living in areas with higher crime rates, often support stricter regulations, while rural voters, who rely on firearms for hunting and protection, staunchly oppose them. This cultural clash isn’t insurmountable, but it requires nuanced dialogue. For example, framing gun control as a public safety issue rather than a cultural attack could foster greater understanding between these groups.

Ultimately, the urban-rural voter divide is a symptom of broader societal fragmentation, driven by geography’s influence on economics, culture, and identity. While these differences may seem irreconcilable, they also present an opportunity for growth. By acknowledging the unique challenges faced by urban and rural communities, politicians and citizens alike can work toward policies that benefit all. Practical steps include fostering rural-urban partnerships, investing in infrastructure that connects these regions, and promoting educational exchanges to build empathy. The goal isn’t to erase differences but to create a political landscape where geography unites rather than divides. After all, the strength of any democracy lies in its ability to represent the diverse needs of its people, regardless of where they live.

Switching to Independent: A Step-by-Step Guide to Changing Political Parties

You may want to see also

Regional economic policies

Geography has long shaped the economic priorities of political parties, particularly in the United States, where regional differences in resources, industries, and demographics have driven distinct policy agendas. The Democratic and Republican parties, for instance, have historically championed economic policies that align with the needs and characteristics of their geographic strongholds. Understanding these regional economic policies reveals how geography not only influences political platforms but also perpetuates ideological divides.

Consider the Rust Belt, a region once dominated by manufacturing and heavy industry. As factories closed and jobs moved overseas, this area became a focal point for Democratic policies aimed at economic revitalization. Proposals like infrastructure investment, workforce retraining, and trade protections resonate here because they address the specific challenges of deindustrialization. In contrast, Republican policies in this region often emphasize deregulation and tax cuts to attract new businesses, reflecting a belief in market-driven solutions. The geographic concentration of economic decline in the Rust Belt has thus become a battleground for competing visions of economic recovery.

In the South and rural Midwest, agriculture plays a central role in shaping regional economic policies. Republicans have traditionally advocated for subsidies, lower taxes, and reduced environmental regulations to support farmers, aligning with the region’s reliance on commodity crops and livestock. Democrats, meanwhile, have pushed for policies like rural broadband expansion and renewable energy initiatives, aiming to diversify rural economies and address long-term sustainability. These divergent approaches highlight how geography—specifically the dominance of agriculture in certain regions—dictates the economic priorities of each party.

The West Coast and Northeast, with their tech-driven economies and urban centers, present another geographic contrast. Democrats in these regions often prioritize policies like green energy investment, public transportation, and affordable housing to address the challenges of rapid growth and high living costs. Republicans, on the other hand, tend to focus on reducing corporate taxes and minimizing government intervention to foster innovation and entrepreneurship. Here, geography influences not just the type of economic policies but also the values they embody, such as sustainability versus free-market growth.

To implement effective regional economic policies, policymakers must consider the unique geographic context of each area. For example, a one-size-fits-all approach to job creation will fail in regions with distinct economic bases. Instead, tailored strategies—such as investing in renewable energy in the Southwest or supporting maritime industries in the Pacific Northwest—can maximize impact. Caution should be taken, however, to avoid policies that exacerbate regional inequalities or neglect long-term environmental and social costs. By grounding economic policies in geographic realities, both parties can better address the diverse needs of their constituents and bridge the divides created by regional disparities.

Hobbes' Political Philosophy: Leviathan, Absolutism, and Human Nature Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of state boundaries

State boundaries have long served as invisible yet powerful architects of political identity, shaping the contours of the two major U.S. political parties. Consider the Electoral College, where the winner-takes-all system in most states amplifies the influence of geographically concentrated voter blocs. In swing states like Pennsylvania or Wisconsin, the physical boundaries of these states become battlegrounds, with parties tailoring messages to resonate with regional concerns—manufacturing jobs in the Rust Belt, for instance. This geographic focus often overshadows national issues, as candidates prioritize winning states over winning hearts and minds uniformly.

The impact of state boundaries extends beyond elections, influencing policy priorities and legislative agendas. Red and blue states often diverge sharply on issues like gun control, healthcare, and environmental regulation, reflecting the geographic distribution of industries and cultural values. For example, agricultural states like Iowa or Kansas tend to favor policies benefiting rural economies, while urbanized states like California or New York push for progressive initiatives like public transit and green energy. These boundaries create echo chambers, reinforcing partisan divides as neighboring states adopt contrasting policies that rarely bridge the physical and ideological gaps between them.

To understand the practical implications, examine how state boundaries affect resource allocation. Federal funding for infrastructure, education, or disaster relief is often distributed based on state-level data, such as population density or economic output. This system can disadvantage smaller or less populous states, whose needs may be overshadowed by larger neighbors. For instance, while Texas receives substantial funding for border security, New Mexico, sharing the same border, may receive less despite similar challenges. This geographic disparity perpetuates inequality, as state boundaries dictate who gets what, often regardless of need.

A cautionary tale lies in the gerrymandering of state boundaries to manipulate political outcomes. By redrawing district lines to favor one party, state legislatures can dilute the voting power of opposition strongholds. This practice, while legal in many states, undermines democratic principles by prioritizing geography over representation. For example, North Carolina’s congressional map has been repeatedly challenged for packing Democratic voters into a few districts, ensuring Republican dominance in others. Such tactics highlight how state boundaries, when weaponized, can distort the political landscape.

In conclusion, state boundaries are not mere administrative lines but active agents in shaping the two-party system. They dictate electoral strategies, policy agendas, resource distribution, and even the fairness of representation. To navigate this geographic influence, voters and policymakers must recognize how physical boundaries intersect with political ones, fostering a more nuanced understanding of partisan dynamics. By doing so, they can work toward bridging divides that state lines too often reinforce.

Global Safe Havens: Countries Offering Political Asylum to Refugees

You may want to see also

Geography and campaign strategies

Geography has long dictated the contours of political campaigns, shaping where candidates focus their efforts, how they tailor their messages, and which voter demographics they prioritize. Consider the Electoral College system in the United States, where swing states like Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin become battlegrounds due to their geographic position and demographic makeup. Campaigns allocate disproportionate resources to these states, often ignoring solidly red or blue states, regardless of their population size. This strategy underscores how geography forces campaigns to think tactically, optimizing for electoral votes rather than popular support.

To leverage geography effectively, campaigns must analyze regional issues and cultural nuances. For instance, a candidate campaigning in rural Iowa might emphasize agricultural policy and trade agreements, while in urban California, the focus shifts to climate change and tech industry regulation. This geographic tailoring extends to advertising, with campaigns using local media outlets and regional social media targeting. Practical tip: Campaigns should invest in geospatial data tools to map voter behavior, identify high-turnout precincts, and allocate resources efficiently. Ignoring these tools risks misaligning efforts with geographic realities.

A comparative analysis reveals how geography amplifies or diminishes campaign strategies. In sprawling states like Texas, door-to-door canvassing is less feasible, pushing campaigns toward digital outreach and large-scale rallies. Conversely, in densely populated New Hampshire, grassroots efforts yield higher returns. Caution: Over-relying on a single geographic strategy can backfire. For example, a campaign focused solely on urban centers may alienate rural voters, whose support can be pivotal in close races. Balancing geographic approaches is key to avoiding such pitfalls.

Finally, geography influences the timing and intensity of campaign efforts. Early primary states like Iowa and New Hampshire receive outsized attention, setting the tone for the entire race. Campaigns must front-load resources into these states, often at the expense of later contests. Takeaway: Geography is not just a backdrop for campaigns but an active player that demands strategic adaptation. By understanding its role, campaigns can craft more effective, geographically informed strategies that resonate with diverse electorates.

Was Alexander Hamilton a Champion of Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Geography played a significant role in shaping the early political divide between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Federalists, strong in the Northeast, favored a centralized government and industrial economy, reflecting the region's commercial interests. Democratic-Republicans, dominant in the South and West, advocated for states' rights and agrarianism, aligning with their agricultural and expansive territorial interests.

In the 19th century, the Democratic Party drew strong support from the agrarian South, emphasizing states' rights and rural interests. The Republican Party, rooted in the industrial North, focused on economic modernization and abolitionism. The North-South divide, driven by economic and social differences tied to geography, solidified these party identities.

Today, geography remains a key factor in party alignment. Democrats dominate urban areas and coastal states, reflecting diverse populations and progressive values. Republicans are stronger in rural and suburban areas, particularly in the South and Midwest, where conservative values and economic policies resonate. Regional economic disparities and cultural differences tied to geography perpetuate this divide.