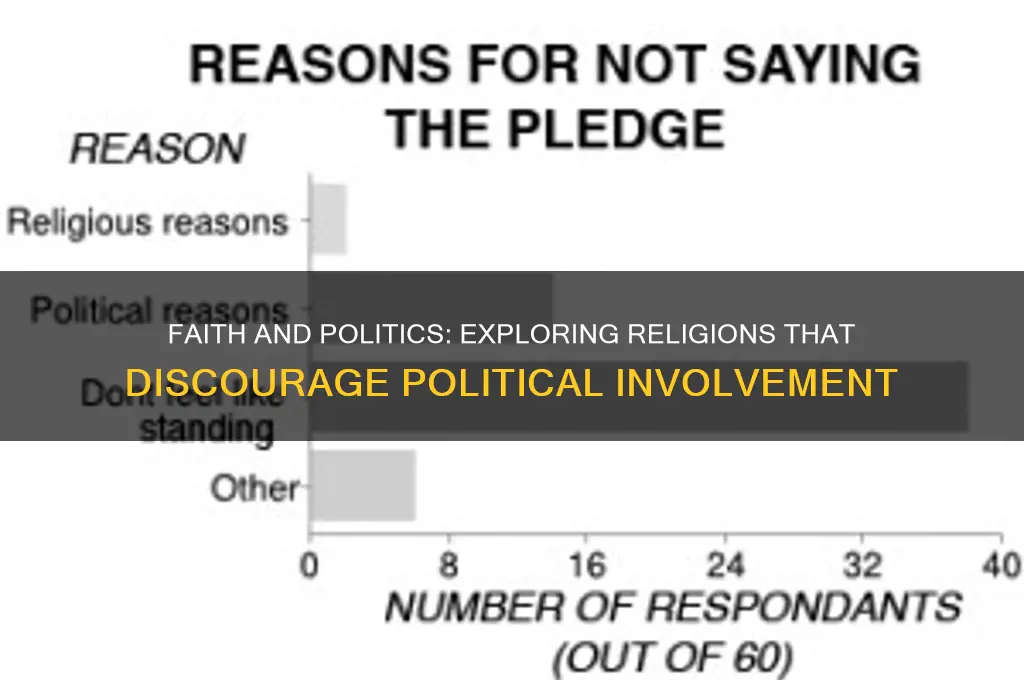

Several religions around the world impose varying degrees of restrictions on political involvement, often rooted in their theological principles or historical contexts. For instance, Jehovah’s Witnesses are well-known for their neutrality in political and secular affairs, abstaining from voting, military service, and other forms of political engagement, as they believe their allegiance belongs solely to God’s Kingdom. Similarly, some Buddhist traditions, particularly those following the Theravada school, emphasize detachment from worldly matters, including politics, to focus on spiritual liberation. In certain interpretations of Hinduism, the concept of *dharma* (righteous duty) may discourage direct political action, especially for those in monastic or ascetic paths. Additionally, some Christian denominations, such as the Amish and certain Mennonite groups, limit political participation to maintain their communal identity and focus on spiritual priorities. These prohibitions often reflect broader religious teachings about humility, non-attachment, and the separation of spiritual and secular realms.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Religious Pacifism and Non-Engagement: Beliefs promoting peace, avoiding political conflict, and focusing on spiritual matters

- Separation of Church and State: Doctrines emphasizing distinct roles for religion and government

- Apolitical Monastic Orders: Communities dedicated to spiritual life, rejecting worldly and political involvement

- Scriptural Prohibitions: Texts forbidding followers from participating in political activities or governance

- Neutrality in Secular Affairs: Teachings advocating detachment from political systems to maintain religious purity

Religious Pacifism and Non-Engagement: Beliefs promoting peace, avoiding political conflict, and focusing on spiritual matters

Religious pacifism and non-engagement are central tenets in several faith traditions that prioritize peace, spiritual growth, and the avoidance of political conflict. These beliefs often stem from interpretations of sacred texts, historical contexts, or the teachings of spiritual leaders, emphasizing a focus on inner transformation rather than external power struggles. One prominent example is Jainism, which advocates for *ahimsa* (non-violence) as a core principle. Jains believe in minimizing harm to all living beings and view political involvement as a potential source of conflict and violence. As such, they traditionally abstain from political activities, concentrating instead on personal purity and spiritual liberation. This non-engagement extends to avoiding professions or roles that might require causing harm, such as those in law enforcement or governance.

Another religion that promotes non-engagement with political action is Buddhism, particularly in its Theravada tradition. The Buddha taught that attachment to worldly matters, including political power, leads to suffering. Monks and devout lay followers often distance themselves from politics, focusing on meditation, mindfulness, and the pursuit of enlightenment. While Buddhism does not universally prohibit political participation, its core teachings encourage detachment from systems that foster division or violence. This spiritual focus aligns with the broader goal of achieving inner peace and harmony, which is seen as more valuable than external influence or control.

Christian Quakerism (the Religious Society of Friends) is a notable example within the Abrahamic traditions. Quakers believe in the inner light of God within every person and emphasize pacifism, simplicity, and integrity. Historically, Quakers have avoided political office and military service, viewing these as incompatible with their commitment to non-violence and spiritual purity. Their testimony of peace extends to advocating for social justice through non-violent means, but they generally refrain from direct political engagement, preferring to work through moral persuasion and community-based efforts. This stance reflects their belief that true change comes from individual and collective spiritual transformation rather than political power.

The Amish and Mennonite communities also embody religious pacifism and non-engagement with politics. Rooted in Anabaptist Christianity, these groups interpret Jesus’ teachings as a call to non-resistance and separation from worldly systems. They avoid voting, holding public office, or participating in military activities, believing that their primary allegiance is to God’s kingdom rather than earthly governments. This non-engagement is not passive but stems from a proactive commitment to living simply, peacefully, and in harmony with their faith. Their focus remains on building and sustaining spiritual communities rather than influencing political structures.

Finally, Taoism offers a philosophical and spiritual framework that discourages attachment to political power and conflict. Taoist teachings emphasize living in harmony with the *Dao* (the natural order of the universe) and avoiding actions that disrupt this balance. While Taoism does not explicitly prohibit political involvement, its principles of wu wei (effortless action) and humility encourage practitioners to avoid positions of power and conflict. Instead, followers are urged to cultivate personal wisdom, simplicity, and alignment with nature, viewing political struggles as distractions from the deeper spiritual path. This perspective aligns with the broader theme of religious pacifism and non-engagement, prioritizing inner peace over external influence.

In summary, religious pacifism and non-engagement are deeply rooted in traditions such as Jainism, Buddhism, Quakerism, Anabaptist Christianity, and Taoism. These faiths promote peace, spiritual growth, and detachment from political conflict, often interpreting sacred teachings as a call to focus on inner transformation rather than external power dynamics. By avoiding political action, adherents seek to live in accordance with their spiritual values, fostering harmony within themselves and their communities while minimizing harm in the broader world.

Can Canadian Political Parties Legally Own Property? Exploring the Rules

You may want to see also

Separation of Church and State: Doctrines emphasizing distinct roles for religion and government

The concept of Separation of Church and State is rooted in the idea that religious institutions and governmental bodies should operate independently, each respecting the distinct roles and boundaries of the other. This principle is not merely a modern political construct but is deeply embedded in the doctrines and practices of several religions that explicitly prohibit or discourage direct political involvement. Such religions emphasize spiritual guidance over temporal governance, advocating for a clear demarcation between faith and politics. This separation ensures that religious principles do not dictate state policies and that political power does not corrupt religious integrity.

One prominent example is Jainism, a religion that strongly emphasizes non-violence (ahimsa) and personal spiritual liberation. Jain doctrine encourages adherents to focus on individual enlightenment rather than engaging in political activities. Jains believe that political involvement could lead to violence, attachment, or harm, which contradicts their core principles. Similarly, Buddhism often promotes detachment from worldly affairs, including politics. While Buddhism does not outright forbid political participation, many Buddhist traditions encourage monks and devout practitioners to prioritize meditation, mindfulness, and spiritual growth over political engagement, viewing such involvement as a distraction from the path to enlightenment.

Quakerism (Society of Friends) is another religious tradition that historically has emphasized the separation of religious and political spheres, though in a nuanced way. Quakers advocate for pacifism, equality, and social justice, but their approach to political action is often indirect, focusing on moral persuasion rather than direct governance. Early Quakers avoided holding political office to maintain their commitment to non-violence and simplicity. This stance reflects a belief that religious values should influence personal behavior and societal norms rather than be codified into law through political power.

In Christianity, certain denominations, such as the Amish and Mennonites, practice a form of separation from political action based on their interpretation of biblical teachings. These groups often cite Jesus’ statement, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:21), to justify their focus on spiritual matters over political involvement. They believe that their primary mission is to live out their faith through community and personal piety rather than seeking political influence. This doctrine of non-conformity to the world extends to avoiding roles in government, military, or other institutions that might compromise their religious values.

Finally, Hinduism, while diverse in its practices and beliefs, includes traditions that discourage political action in favor of spiritual pursuits. Ascetics and renunciants (sannyasis) in Hinduism often withdraw from societal and political life to focus on moksha (liberation). This withdrawal is seen as a higher calling, transcending the material and political world. Though Hinduism has historically influenced political thought in India, the religion itself contains doctrines that prioritize spiritual over temporal authority, advocating for a separation between religious duties and political power.

In summary, the doctrine of Separation of Church and State finds resonance in various religions that prohibit or minimize political action. These faiths emphasize spiritual growth, non-violence, and detachment from worldly power, viewing political involvement as a potential distraction or corruption of their core principles. By maintaining distinct roles for religion and government, these traditions seek to preserve the integrity of both spheres, ensuring that faith remains a guiding light rather than a tool for political control.

Understanding the Political Center: Who Stands in the Middle?

You may want to see also

Apolitical Monastic Orders: Communities dedicated to spiritual life, rejecting worldly and political involvement

Apolitical monastic orders represent a profound commitment to spiritual life, deliberately distancing themselves from worldly and political involvement. These communities, often rooted in religions such as Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Jainism, prioritize inner transformation, prayer, meditation, and service to others over external power structures. By rejecting political engagement, they seek to maintain a singular focus on their spiritual goals, avoiding distractions that could compromise their devotion. This apolitical stance is not merely passive but a conscious choice to cultivate a life of simplicity, contemplation, and detachment from temporal concerns.

In Buddhism, certain monastic orders, such as the Theravada tradition, emphasize renunciation of worldly affairs, including politics. Monks and nuns adhere to the Vinaya, a code of discipline that discourages involvement in secular matters. Their lives revolve around meditation, study of the Dharma, and ethical conduct, with the ultimate aim of achieving Nirvana. Engaging in political activities is seen as a hindrance to this spiritual path, as it fosters attachment and conflict, which are antithetical to the teachings of the Buddha. Similarly, the Forest Tradition in Thailand exemplifies this apolitical approach, with monks living in remote areas to deepen their spiritual practice away from societal influences.

Christian monasticism, particularly in traditions like the Carthusian and Trappist orders, also embodies apolitical principles. These communities follow the Rule of Saint Benedict or other monastic rules that stress prayer, work, and silence. Trappist monks, for instance, take a vow of stability, committing to a life of seclusion and contemplation. Their focus on the "prayer of the heart" and manual labor leaves no room for political involvement. The Carthusians, known for their extreme asceticism, live in complete isolation, dedicating their lives to God without any engagement in external affairs. These orders view political participation as a distraction from their divine calling.

Hinduism and Jainism also host apolitical monastic orders that reject worldly and political involvement. In Hinduism, *sannyasis* (renunciants) abandon material possessions and societal roles to pursue *moksha* (liberation). They often live as ascetics, wandering or residing in ashrams, and are explicitly instructed to avoid political affairs. Jain monks and nuns follow strict vows of non-violence (*ahimsa*), truthfulness, and non-attachment, living a life of austerity and meditation. Their focus on spiritual purification and liberation from the cycle of rebirth leaves no space for political engagement. These traditions emphasize that true spiritual progress requires detachment from worldly power and conflict.

Apolitical monastic orders serve as a testament to the enduring value of spiritual life in a world often dominated by political and material concerns. By rejecting political involvement, these communities preserve a space for contemplation, prayer, and inner transformation. Their existence reminds society of the importance of transcending temporal conflicts to seek higher truths. In a world where politics often divides, these orders offer a unifying message of peace, compassion, and the pursuit of the divine, demonstrating that true fulfillment lies beyond the realm of worldly power.

Jeff Bezos' Political Leanings: Uncovering His Party Affiliations and Donations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Scriptural Prohibitions: Texts forbidding followers from participating in political activities or governance

While many religions encourage civic engagement, some traditions emphasize detachment from worldly power structures, including politics. This detachment is often rooted in scriptural prohibitions or interpretations that prioritize spiritual pursuits over temporal governance. Here are some examples:

Jainism and Non-Violence:

Jainism, a dharmic religion from ancient India, places absolute emphasis on *ahimsa* (non-violence). This principle extends beyond physical harm to encompass any action that might cause suffering, including involvement in systems that perpetuate violence or inequality. Jains believe that political participation, with its inherent potential for conflict and compromise, risks violating this core tenet. The *Tattvartha Sutra*, a key Jain text, emphasizes renunciation of worldly attachments, including power and influence, as essential for spiritual liberation.

Jains traditionally avoid positions of authority that might require them to make decisions leading to harm, even indirectly. This often translates to a historical and cultural aversion to active political involvement.

Early Christianity and the "Render unto Caesar" Principle:

Jesus Christ's statement in the Gospels, "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's" (Mark 12:17), has been interpreted in various ways. Some early Christian communities, particularly those facing persecution under the Roman Empire, understood this as a call to separate themselves from the political realm, focusing solely on their spiritual kingdom. This interpretation, while not universally held, led to a tradition of Christian asceticism and monasticism, where individuals withdrew from societal structures, including politics, to dedicate themselves fully to God.

The Epistles of Paul further emphasize the focus on spiritual matters, urging believers to live peacefully and avoid entanglement in worldly disputes (Romans 13:13-14).

Buddhism and the Middle Way:

Buddhism, originating in India, advocates the "Middle Way," avoiding extremes of indulgence and self-mortification. While not explicitly prohibiting political participation, the Buddha's teachings emphasize detachment from worldly desires and the pursuit of enlightenment. The *Dhammapada*, a collection of the Buddha's teachings, encourages followers to cultivate inner peace and wisdom rather than seeking external power or influence.

Some Buddhist traditions, particularly those influenced by Mahayana Buddhism, emphasize compassion and social responsibility. However, even within these traditions, the focus remains on individual transformation and alleviating suffering through personal actions rather than systemic change through political means.

The Amish and Separation from the World:

The Amish, a Christian denomination known for their simple living and resistance to modern technology, adhere to a strict interpretation of the Bible's call to be "in the world but not of it" (John 17:16). This translates to a deliberate separation from mainstream society, including its political institutions. Amish communities prioritize their internal governance structures based on biblical principles and consensus-building, avoiding involvement in external political processes.

They believe that participating in politics would compromise their commitment to pacifism, non-resistance, and the primacy of their faith community.

These examples illustrate how scriptural interpretations and core religious principles can lead to prohibitions on political action. It's important to note that these interpretations are not universal within each religion and that individuals and communities may hold varying views on the appropriate level of engagement with the political sphere.

Exploring the Political Landscape: Do Parties Dominate Philippine Politics?

You may want to see also

Neutrality in Secular Affairs: Teachings advocating detachment from political systems to maintain religious purity

Several religious traditions advocate for neutrality in secular affairs, emphasizing detachment from political systems to preserve spiritual integrity and focus on higher moral or divine principles. This stance often stems from teachings that prioritize inner transformation over external power structures, viewing political engagement as a potential distraction or corrupting influence. Below are detailed explorations of this theme across different faiths.

Jainism: Non-Violence and Non-Attachment

Jainism, an ancient Indian religion, promotes *ahimsa* (non-violence) and *aparigraha* (non-attachment) as core principles. Jains believe that involvement in political systems, which inherently involve conflict and decision-making that may cause harm, contradicts these ideals. Monks and nuns in Jainism are particularly expected to renounce worldly affairs, including politics, to focus on spiritual liberation. Even lay Jains are encouraged to minimize their engagement in political activities, as such involvement could lead to karmic entanglements that hinder spiritual progress. This detachment is seen as essential for maintaining religious purity and adhering to the path of non-violence.

Buddhism: The Middle Way and Renunciation

Buddhism teaches the Middle Way, a path that avoids extremes, including excessive involvement in worldly matters. The Buddha discouraged monks and nuns from participating in political affairs, advising them to focus on meditation, wisdom, and compassion. While lay Buddhists are not prohibited from political engagement, the teachings emphasize that such involvement should be guided by ethical principles and not driven by attachment to power or outcomes. The concept of *right livelihood* in the Noble Eightfold Path further underscores the importance of avoiding professions or activities that cause harm, including those tied to political systems. Detachment from political strife is viewed as a means to cultivate inner peace and enlightenment.

Christian Anabaptist Traditions: Separation from the World

Within Christianity, Anabaptist groups such as the Amish, Mennonites, and Hutterites advocate for separation from worldly systems, including politics. Rooted in interpretations of Jesus’ teachings about rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s (Matthew 22:21), these groups emphasize spiritual citizenship over political allegiance. They often abstain from voting, holding public office, or participating in military service, believing that their primary loyalty is to God’s kingdom rather than earthly governments. This neutrality is seen as a way to preserve their distinct religious identity and avoid compromising their faith through entanglement in secular power struggles.

Taoism: Harmony and Non-Action (*Wu Wei*)

Taoism encourages adherents to align with the natural flow of the universe, often through the principle of *wu wei*, or effortless action. This philosophy extends to political engagement, advocating for minimal interference in societal affairs. Taoist sages historically advised rulers to govern with simplicity and humility, avoiding excessive laws or force. For individual practitioners, detachment from political systems is seen as a way to maintain harmony with the Tao, or the fundamental nature of the universe. By avoiding the complexities and conflicts of politics, Taoists seek to cultivate inner balance and spiritual clarity, prioritizing personal and communal harmony over external influence.

Hindu Ascetic Traditions: Renunciation for Spiritual Liberation

Within Hinduism, ascetic traditions such as *sannyasa* emphasize renunciation of worldly attachments, including political involvement, as a path to spiritual liberation (*moksha*). Sannyasis, or renunciants, are expected to withdraw from societal roles, including those related to governance or politics, to focus on self-realization and devotion to God. This detachment is rooted in the belief that political engagement can lead to egoism, desire, and karma, which bind the soul to the cycle of rebirth. By maintaining neutrality in secular affairs, ascetics uphold their commitment to transcending material existence and attaining union with the divine.

These teachings collectively illustrate how neutrality in secular affairs is often seen as a means to safeguard religious purity, foster spiritual growth, and avoid the moral compromises inherent in political systems. While the specifics vary across traditions, the underlying principle remains consistent: detachment from worldly power structures is essential for achieving higher spiritual or ethical goals.

Why Hot Button Issues Dominate Modern Political Discourse and Divide Us

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While no major religion universally prohibits all political action, some interpretations of religions like Buddhism, Jainism, and certain Christian denominations (e.g., Anabaptists like Amish or Mennonites) emphasize non-involvement in secular governance, focusing instead on spiritual or communal matters.

No, Buddhism does not universally prohibit political action. However, some Buddhist traditions, particularly those following the Theravada school, emphasize detachment from worldly affairs, including politics, to focus on spiritual liberation.

No, Islam does not prohibit political action. In fact, many Muslims actively engage in politics, and Islamic history includes examples of political leadership and governance. However, interpretations vary, and some individuals or groups may prioritize religious duties over political involvement.

Yes, some Christian denominations, such as the Amish, Mennonites, and certain Quaker groups, discourage or limit political involvement due to their beliefs in non-conformity to the world, pacifism, and separation from secular authority. However, this is not a universal Christian stance.