American political parties face significant challenges that hinder their effectiveness, stemming from deep-rooted structural and cultural factors. Polarization has intensified, driving parties further apart ideologically and reducing opportunities for bipartisan cooperation. The influence of special interests and campaign financing often prioritizes donor agendas over public needs, while gerrymandering and the Electoral College distort representation and incentivize catering to extreme bases. Additionally, the media landscape amplifies partisan divides, and the two-party system limits diverse voices, leaving many voters alienated. These issues collectively undermine parties' ability to govern cohesively and address pressing national challenges.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Polarization | Extreme ideological divide between parties, leading to gridlock and inability to compromise. (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Gerrymandering | Manipulation of district boundaries to favor a specific party, reducing competition and incentivizing extremism. (Brennan Center for Justice, 2023) |

| Campaign Finance | Heavy reliance on wealthy donors and special interests, distorting policy priorities and limiting representation of average citizens. (OpenSecrets, 2023) |

| Primary System | Encourages candidates to appeal to extreme factions within their party during primaries, making it harder to appeal to the broader electorate in general elections. (Brookings Institution, 2022) |

| Filibuster | Senate rule requiring 60 votes to end debate, allowing a minority party to block legislation even if it has majority support. (Congressional Research Service, 2023) |

| Hyper-Partisanship | Focus on party loyalty over policy solutions, leading to a lack of trust and cooperation between parties. (Gallup, 2023) |

| Media Echo Chambers | Fragmented media landscape reinforces existing beliefs and discourages exposure to opposing viewpoints. (Pew Research Center, 2022) |

| Lack of Incentives for Bipartisanship | Political rewards often come from partisan attacks and obstruction, rather than collaboration and compromise. (American Political Science Association, 2021) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Polarization and Ideological Rigidity: Extreme partisan divides hinder compromise and collaborative governance

- Gerrymandering and Safe Seats: Manipulated districts reduce competitive elections and accountability

- Money in Politics: Campaign financing skews priorities toward donors, not voters

- Primary System Dysfunction: Extremist bases dominate primaries, sidelining moderate candidates

- Filibuster and Gridlock: Senate rules stall legislation, fostering inaction and frustration

Polarization and Ideological Rigidity: Extreme partisan divides hinder compromise and collaborative governance

American political parties are increasingly trapped in a cycle of polarization and ideological rigidity, where extreme partisan divides stifle compromise and collaborative governance. This phenomenon is not merely a symptom of political disagreement but a structural barrier to effective party operation. Consider the 2013 government shutdown, triggered by partisan deadlock over the Affordable Care Act. Such events illustrate how ideological entrenchment prioritizes party purity over legislative progress, leaving critical issues unresolved.

To understand this dynamic, examine the role of primary elections. These contests often favor candidates who appeal to their party’s most extreme factions, rewarding ideological purity over pragmatism. For instance, a moderate Republican in a deep-red district may face a primary challenger who accuses them of insufficient conservatism, pushing the party further right. This mechanism amplifies polarization, as elected officials feel compelled to adopt rigid stances to secure their base’s support. The result? A Congress where compromise is seen as betrayal rather than statesmanship.

The media ecosystem exacerbates this trend by incentivizing outrage and reinforcing echo chambers. Cable news networks and social media platforms thrive on conflict, amplifying extreme voices while marginalizing moderate perspectives. A 2021 Pew Research study found that 55% of Americans believe the other party is a threat to the nation’s well-being, a sentiment fueled by partisan media narratives. This us-versus-them mentality makes bipartisan cooperation seem not just difficult but dangerous, further entrenching ideological rigidity.

Breaking this cycle requires deliberate institutional reforms. One practical step is to adopt open or ranked-choice primaries, which encourage candidates to appeal to a broader electorate rather than just their party’s extremes. Another is to restructure legislative rules, such as eliminating the filibuster in the Senate, to reduce the power of obstructionist minorities. Additionally, politicians and citizens alike must prioritize issue-based engagement over party loyalty. For example, a voter concerned about climate change should support policies addressing it, regardless of the party proposing them.

Ultimately, polarization and ideological rigidity are self-reinforcing mechanisms that undermine American political parties’ ability to govern effectively. While reversing this trend is challenging, it is not insurmountable. By reforming institutions, rethinking media consumption, and fostering a culture of pragmatic problem-solving, parties can move beyond partisan gridlock. The alternative—continued stagnation and dysfunction—is a price no democracy can afford.

Why Political Villains Are Essential for Democracy and Progress

You may want to see also

Gerrymandering and Safe Seats: Manipulated districts reduce competitive elections and accountability

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party, has become a cornerstone of modern American politics. By manipulating district lines, parties create "safe seats" where their candidates face little to no competition in general elections. This tactic, while legally permissible in many states, undermines democratic principles by reducing the number of competitive races and diminishing voter accountability. For instance, in the 2020 House elections, only 38 races out of 435 were decided by a margin of 5% or less, a stark indicator of how gerrymandering stifles electoral competition.

Consider the mechanics of gerrymandering: it involves packing opposition voters into a few districts or cracking them across multiple districts to dilute their influence. In North Carolina, for example, Republicans drew maps in 2016 that resulted in 10 GOP seats and only 3 Democratic seats, despite a nearly even split in statewide votes. Such manipulation ensures incumbents face minimal risk of losing their seats, fostering complacency and reducing the incentive to represent diverse constituent interests. The result? Lawmakers prioritize party loyalty over responsive governance, further polarizing the political landscape.

The consequences of safe seats extend beyond individual districts. When elections are non-competitive, voter turnout plummets. Why participate when the outcome is all but predetermined? In 2018, districts with competitive races saw turnout rates 10-15% higher than those with safe seats. Low turnout disproportionately affects marginalized communities, whose voices are further silenced in a system rigged against them. This cycle of disengagement weakens the legitimacy of elected officials and erodes public trust in democratic institutions.

To combat gerrymandering, some states have adopted independent redistricting commissions. California’s commission, established in 2010, has produced maps that reflect population diversity and encourage competitive races. Similarly, Michigan’s 2018 ballot initiative transferred redistricting power from the legislature to an independent body, leading to fairer maps in 2022. These reforms demonstrate that structural changes can restore accountability and competition to elections. However, their success depends on widespread adoption, as gerrymandering in one state can offset progress in another.

Ultimately, gerrymandering and safe seats are not just technical issues but threats to the health of American democracy. They distort representation, suppress voter engagement, and entrench political power. Addressing this problem requires a multi-pronged approach: legal challenges, state-level reforms, and public pressure. Until then, the promise of "one person, one vote" remains elusive, and the effectiveness of American political parties will continue to be compromised by manipulated districts.

Copenhagen's Political Focus: Unraveling the Absence of Cultural and Social Dimensions

You may want to see also

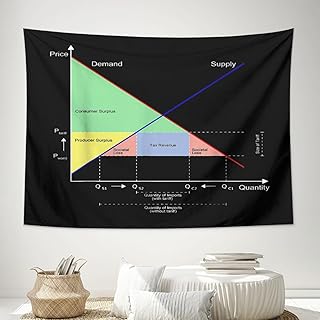

Money in Politics: Campaign financing skews priorities toward donors, not voters

The influence of money in American politics has become a pervasive force, distorting the democratic process and skewing priorities away from the needs of voters. Campaign financing, in particular, has created a system where politicians are more accountable to their donors than to the constituents they represent. This dynamic undermines the effectiveness of political parties by prioritizing narrow interests over the broader public good.

Consider the numbers: in the 2020 election cycle, nearly $14.4 billion was spent on federal elections, with a significant portion coming from wealthy individuals, corporations, and special interest groups. These donors often contribute large sums through Political Action Committees (PACs) or Super PACs, which can raise and spend unlimited amounts of money. In return, politicians may feel compelled to advance policies that benefit their financial backers, even if those policies are unpopular or detrimental to the majority of voters. For instance, a study by Princeton University found that policies supported by the wealthy are significantly more likely to become law, while those favored by lower-income voters are often ignored.

This imbalance is further exacerbated by the Supreme Court’s 2010 *Citizens United* decision, which allowed corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts on political campaigns. The ruling opened the floodgates for corporate money to dominate elections, drowning out the voices of ordinary citizens. As a result, issues like healthcare reform, climate change, and income inequality—which consistently rank high among voter concerns—often take a backseat to the agendas of wealthy donors. For example, despite overwhelming public support for universal background checks on gun purchases, legislation has repeatedly stalled due to opposition from well-funded gun rights groups.

To address this issue, several reforms could be implemented. First, public financing of elections could level the playing field by providing candidates with taxpayer-funded resources, reducing their reliance on private donors. Second, stricter campaign finance laws could limit the amount of money individuals and corporations can contribute, while increasing transparency around political spending. Third, overturning *Citizens United* through a constitutional amendment could restore balance by reining in corporate influence. These steps would not only empower voters but also enable political parties to focus on policies that genuinely serve the public interest.

Ultimately, the stranglehold of money in politics is a critical barrier to the effective operation of American political parties. By prioritizing donors over voters, the system perpetuates inequality and erodes trust in democratic institutions. Meaningful reform is essential to reclaiming a government that truly represents the people, not just the wealthiest among them.

Unveiling the Author: Who Wrote the Iconic Politics Book?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99

Primary System Dysfunction: Extremist bases dominate primaries, sidelining moderate candidates

The primary system, designed to democratize candidate selection, has inadvertently become a breeding ground for extremism. Low turnout in primaries—often below 20% of eligible voters—means a small, highly motivated faction can dominate the process. This dynamic empowers ideological purists who prioritize party orthodoxy over electability, sidelining moderates who might appeal to a broader electorate. For instance, in 2010, Tea Party-backed candidates like Christine O’Donnell won Republican primaries but lost in the general election, illustrating how extremist bases can hijack the nomination process.

Consider the mechanics of this dysfunction: primaries reward candidates who cater to the extremes. In safe districts, where the primary is the de facto general election, candidates have little incentive to moderate their views. This creates a feedback loop where politicians increasingly adopt hardline stances to secure their base’s support. The result? A Congress polarized along ideological lines, with moderates marginalized and bipartisan cooperation becoming increasingly rare. Take the 2014 defeat of House Majority Leader Eric Cantor by a Tea Party challenger—a stark reminder of how even established incumbents are vulnerable to extremist pressure.

To break this cycle, parties must rethink primary structures. One solution is open primaries, where all voters, regardless of party affiliation, can participate. This dilutes the influence of extremist bases by incorporating independent and moderate voices. Another approach is ranked-choice voting, which encourages candidates to appeal to a wider spectrum of voters rather than just their party’s fringe. States like Maine and Alaska have already implemented such reforms, offering a blueprint for others to follow.

However, caution is warranted. Open primaries risk allowing members of the opposing party to strategically vote for weaker candidates, a tactic known as “party raiding.” Similarly, ranked-choice voting can complicate the electoral process, potentially reducing voter turnout if not properly explained. Parties must balance these risks with the need to reclaim their nominating processes from extremist control.

Ultimately, the dominance of extremist bases in primaries is not an insurmountable problem but a symptom of a system in need of reform. By restructuring primaries to prioritize broad appeal over ideological purity, parties can foster a political environment where moderation and compromise thrive. The alternative—continued polarization and gridlock—undermines the very effectiveness of American political parties.

Andrew McCabe: His Political Role, Controversies, and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Filibuster and Gridlock: Senate rules stall legislation, fostering inaction and frustration

The filibuster, a Senate procedural tactic allowing a single senator to delay or block a vote on legislation, has become a symbol of legislative gridlock in American politics. This mechanism, rooted in the Senate's tradition of unlimited debate, requires a supermajority of 60 votes to invoke cloture and end debate, effectively giving a minority of senators disproportionate power to stall bills. While proponents argue it encourages bipartisanship, critics contend it paralyzes governance, preventing timely action on critical issues. For instance, the 2010 filibuster of the DREAM Act, which would have provided a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children, highlighted how a minority can thwart majority will, even on broadly supported measures.

Consider the practical implications of this rule. A senator can initiate a filibuster simply by refusing to yield the floor, forcing the majority to secure 60 votes to proceed. This process not only delays legislation but also consumes valuable floor time, often sidelining other important bills. The result is a backlog of critical measures—from healthcare reform to climate change initiatives—that languish in legislative limbo. For example, the 2013 filibuster of gun control legislation following the Sandy Hook shooting demonstrated how the filibuster can stymie even emotionally charged, public-supported reforms, leaving constituents frustrated and disillusioned with the political process.

To address this gridlock, reformers propose targeted changes to Senate rules. One suggestion is to eliminate the 60-vote threshold for cloture, replacing it with a "talking filibuster," which would require senators to actively hold the floor to sustain a filibuster. This change would increase the cost of obstruction, as senators would need to physically maintain their filibuster, potentially limiting its overuse. Another proposal is to reduce the cloture threshold to a simple majority for certain types of legislation, such as appropriations bills, to ensure essential government functions are not held hostage to partisan brinkmanship. These reforms aim to balance the need for deliberation with the imperative of effective governance.

However, implementing such changes is fraught with challenges. The filibuster is deeply entrenched in Senate culture, and altering it requires unanimous consent or a rule change via the "nuclear option," which itself carries significant political risks. Critics argue that eliminating or weakening the filibuster could lead to unchecked majority power, eroding minority rights and fostering partisan extremism. Proponents counter that the current system already marginalizes minorities by allowing a vocal minority to dictate policy, often at the expense of broader public interest. Striking a balance between protecting minority rights and ensuring legislative functionality remains a delicate and contentious task.

Ultimately, the filibuster and resulting gridlock exemplify the tension between tradition and progress in American politics. While the Senate's deliberative nature is a cornerstone of its identity, the filibuster's modern application often undermines its intended purpose, fostering inaction rather than thoughtful debate. Addressing this issue requires a nuanced approach—one that preserves the Senate's unique role while adapting its rules to meet the demands of a rapidly changing world. Without such reforms, the filibuster will continue to serve as a barrier to effective governance, perpetuating frustration and disillusionment among both lawmakers and the public they serve.

Exploring Germany's Political Landscape: A Comprehensive Guide to Its Parties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Polarization deepens ideological divides between parties, making compromise and bipartisan cooperation increasingly difficult. This leads to legislative gridlock, as neither party is willing to cede ground on key issues, hindering effective governance.

Gerrymandering allows parties to manipulate district boundaries to favor their candidates, reducing competitive elections. This creates safe seats for incumbents, discouraging moderation and incentivizing extreme positions to appeal to the party base, rather than the broader electorate.

Special interests and lobbying often prioritize narrow agendas over the public good, distorting party priorities. This can lead to policies that benefit specific groups at the expense of broader societal needs, undermining trust in political parties and their ability to govern effectively.

The two-party system marginalizes diverse viewpoints by funneling political power into two dominant parties. This excludes smaller parties and independent voices, stifling innovation and limiting the range of policy solutions available to address complex national issues.