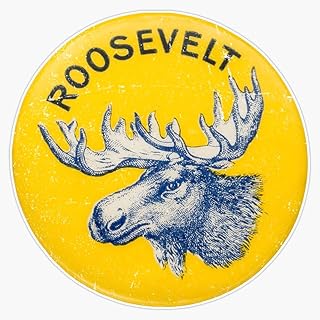

Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States, famously broke away from the Republican Party in 1912 to form the Progressive Party, often referred to as the Bull Moose Party. This move was driven by his dissatisfaction with the conservative policies of his successor, William Howard Taft, and the Republican Party's resistance to his progressive reforms. Roosevelt ran as the Progressive Party's presidential candidate in the 1912 election, advocating for a platform that included social justice, trust-busting, and labor rights. Although he did not win the presidency, his third-party campaign significantly reshaped American politics and highlighted the growing divide between progressive and conservative factions within the Republican Party.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Progressive Party (1912) |

| Nickname | Bull Moose Party |

| Founder | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Year Founded | 1912 |

| Ideology | Progressivism, Social Justice, Conservationism, Trust Busting |

| Key Platform | New Nationalism (Roosevelt's vision for active government intervention in social and economic issues) |

| Notable Candidates | Theodore Roosevelt (Presidential candidate, 1912) |

| Election Performance (1912) | 27.4% of the popular vote, 88 electoral votes (2nd place) |

| Dissolution | 1920 (effectively disbanded after 1916 election) |

| Legacy | Influenced modern progressive policies, pushed for women's suffrage, worker's rights, and environmental protection |

| Symbol | Bull Moose |

| Notable Policies | Women's suffrage, minimum wage, social security, antitrust legislation, conservation of natural resources |

| Relationship to Major Parties | Split from the Republican Party due to disagreements with William Howard Taft |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Progressive Party (Bull Moose): Roosevelt's 1912 party, formed after split from Republicans

- Presidential Campaign: Ran against Taft and Wilson, finished second with 27%

- New Nationalism Platform: Advocated progressive reforms, social justice, and government regulation

- Party Dissolution: Declined after 1912; most members rejoined Republicans or Democrats

- Legacy and Influence: Inspired future progressive movements and policies in U.S. politics

Progressive Party (Bull Moose): Roosevelt's 1912 party, formed after split from Republicans

Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party, affectionately dubbed the Bull Moose Party, emerged in 1912 as a bold response to the conservative drift of the Republican Party. Frustrated by incumbent President William Howard Taft’s failure to advance progressive reforms, Roosevelt challenged Taft for the Republican nomination. When Taft secured the nomination through what Roosevelt deemed underhanded tactics, he broke away, forming a third party that would redefine American politics. The party’s nickname originated from Roosevelt’s declaration that he felt “as strong as a bull moose,” a phrase that captured the party’s tenacity and Roosevelt’s indomitable spirit.

The Progressive Party’s platform was a radical departure from the status quo, advocating for sweeping reforms that mirrored Roosevelt’s New Nationalism. Key proposals included federal regulation of corporations, women’s suffrage, social welfare programs, and environmental conservation. The party’s convention in Chicago was a spectacle of democracy, becoming the first to allow women as delegates and to nominate a woman for vice president, though she declined. This inclusivity and forward-thinking agenda attracted a diverse coalition of reformers, labor activists, and disillusioned Republicans, positioning the party as a champion of the common man against entrenched interests.

Despite its innovative platform, the Progressive Party faced significant challenges. The 1912 election was a three-way race between Roosevelt, Taft, and Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson. While Roosevelt’s campaign energized millions, it ultimately split the Republican vote, handing the presidency to Wilson. Roosevelt himself was nearly derailed by an assassination attempt in Milwaukee, where a bullet lodged in his chest, but he famously insisted on delivering his speech before seeking medical attention. Though the party won only 27% of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes, its impact was profound, pushing progressive ideas into the national conversation.

The legacy of the Bull Moose Party lies in its ability to force both major parties to address progressive issues. Many of its proposals, such as the federal income tax, antitrust legislation, and workers’ rights, were later adopted under Wilson’s administration and beyond. The party’s short-lived existence underscores the challenges of third-party politics in a two-party system, yet it remains a testament to Roosevelt’s leadership and vision. For modern reformers, the Bull Moose Party serves as a reminder that bold ideas, even if not immediately victorious, can reshape the political landscape.

To understand the Progressive Party’s significance, consider it as a catalyst rather than a failure. Its platform was a blueprint for future reforms, and its spirit of defiance against political stagnation resonates today. For those seeking to challenge the establishment, the Bull Moose Party offers a practical lesson: organize around clear, transformative goals, build broad coalitions, and remain undeterred by setbacks. Roosevelt’s third-party experiment may not have won the White House, but it won the future, proving that sometimes, the greatest victories are not measured in elections but in the ideas they leave behind.

India's Political Landscape: Exploring Limits on Party Formation and Registration

You may want to see also

1912 Presidential Campaign: Ran against Taft and Wilson, finished second with 27%

The 1912 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, marked by Theodore Roosevelt’s bold decision to run as a third-party candidate. After a falling out with his handpicked successor, William Howard Taft, Roosevelt challenged Taft for the Republican nomination. When Taft secured the nomination, Roosevelt broke away to form the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party. This move set the stage for a three-way race against Taft and the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson. Roosevelt’s campaign was a testament to his enduring popularity and his commitment to progressive reform, but it also highlighted the risks of splitting the Republican vote.

Roosevelt’s platform was ambitious, advocating for sweeping reforms such as women’s suffrage, antitrust legislation, and social welfare programs. His campaign rallies drew massive crowds, and his energy on the trail was unmatched. One of the most dramatic moments occurred when Roosevelt was shot in Milwaukee while delivering a speech. Despite the bullet lodged in his chest, he insisted on finishing his remarks, declaring, “It takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” This incident only bolstered his image as a fearless leader, but it was not enough to secure victory. Wilson ultimately won the election with 42% of the popular vote, while Roosevelt finished second with 27%, leaving Taft with a meager 23%.

Analyzing the results reveals the strategic miscalculations of Roosevelt’s campaign. By splitting the Republican vote, he inadvertently handed the election to Wilson, a candidate whose progressive agenda aligned with many of Roosevelt’s own ideas. Taft’s weak showing underscored the depth of the Republican Party’s internal divisions, but it also demonstrated the limitations of third-party challenges in a two-party system. Roosevelt’s 27% was a remarkable achievement for a third-party candidate, yet it fell short of his goal of reclaiming the presidency. This outcome raises questions about the viability of third-party movements in American politics and the trade-offs between ideological purity and electoral pragmatism.

For those studying political strategy or considering third-party campaigns, the 1912 election offers valuable lessons. First, a charismatic candidate with a strong platform can make a significant impact, even if victory remains elusive. Second, the structural barriers of the electoral system—such as winner-take-all states and ballot access laws—favor established parties. Finally, third-party candidates must carefully weigh the potential consequences of their campaigns, as they can inadvertently benefit their ideological opponents. Roosevelt’s 1912 campaign remains a case study in both the promise and peril of challenging the two-party duopoly.

Practically speaking, anyone inspired by Roosevelt’s example should focus on building a broad coalition and securing ballot access in key states. Modern third-party candidates can leverage social media and grassroots organizing to amplify their message, but they must also navigate the financial and logistical challenges of running without major party support. While Roosevelt’s 27% finish was unprecedented, it serves as a reminder that third-party success often depends on unique historical circumstances and the ability to capitalize on widespread dissatisfaction with the major parties. His campaign remains a powerful example of what can be achieved—and what can go wrong—when a political outsider dares to challenge the status quo.

Understanding the Political Environment: Key Factors and Their Impact

You may want to see also

New Nationalism Platform: Advocated progressive reforms, social justice, and government regulation

Theodore Roosevelt's New Nationalism platform emerged as a bold vision for America, a call to arms for progressive reforms that would reshape the nation's political and social landscape. At its core, this platform advocated for a more active and interventionist government, one that would champion social justice and regulate corporate power to ensure a fair and equitable society.

The Progressive Agenda: A Comprehensive Approach

Roosevelt's New Nationalism was a comprehensive plan, addressing a wide array of issues. It proposed progressive reforms to tackle income inequality, improve labor conditions, and protect consumers. This included advocating for a minimum wage, an eight-hour workday, and the right to collective bargaining. The platform also emphasized the need for social welfare programs, such as old-age pensions and unemployment insurance, to provide a safety net for the most vulnerable citizens. These reforms were not just about economic fairness but also about empowering individuals and communities to thrive.

Social Justice: A Moral Imperative

A key aspect of New Nationalism was its commitment to social justice. Roosevelt believed in using the power of government to correct social wrongs and ensure equal opportunities for all. This meant addressing racial inequality, women's rights, and the plight of immigrants. The platform called for an end to racial discrimination, advocating for voting rights and equal access to education and employment. It also supported women's suffrage, recognizing their essential role in society and the need for their political empowerment. By promoting these social justice measures, Roosevelt aimed to create a more inclusive and just nation.

Government Regulation: Taming Corporate Power

In an era of rapid industrialization and growing corporate influence, Roosevelt's platform emphasized the necessity of government regulation. He argued that unchecked corporate power posed a threat to democracy and the well-being of citizens. New Nationalism proposed regulating interstate commerce, breaking up monopolies, and implementing antitrust laws to promote fair competition. This regulatory approach extended to environmental conservation, with Roosevelt advocating for the responsible management of natural resources. By reining in corporate excesses, the government could protect consumers, workers, and the environment, ensuring a more sustainable and equitable economy.

A Vision for a Modern America

The New Nationalism platform was a forward-thinking agenda, anticipating many of the challenges and issues that modern societies continue to grapple with. Its emphasis on progressive reforms, social justice, and government regulation offers a blueprint for addressing contemporary concerns. For instance, the platform's focus on income inequality and labor rights resonates with today's debates on living wages and workers' rights. Similarly, its commitment to social justice and government intervention provides a framework for tackling systemic racism, gender inequality, and environmental degradation. Roosevelt's vision encourages a proactive role for government in shaping a fair and just society, a principle that remains relevant in the ongoing struggle for progressive change.

In essence, Theodore Roosevelt's New Nationalism platform was a pioneering effort to redefine the role of government in American society. By advocating for progressive reforms, social justice, and strategic regulation, it sought to create a more equitable and prosperous nation. This platform's legacy continues to inspire and guide those striving for a more just and inclusive political and social order.

Vietnam War Leadership: Which Political Party Held Power?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$30.95 $16.98

Party Dissolution: Declined after 1912; most members rejoined Republicans or Democrats

The Progressive Party, often referred to as the Bull Moose Party, faced a rapid decline after the 1912 presidential election, marking a pivotal moment in American political history. Theodore Roosevelt, the party's charismatic leader, had bolted from the Republican Party to challenge incumbent President William Howard Taft, splitting the Republican vote and inadvertently aiding Democrat Woodrow Wilson's victory. Despite Roosevelt's impressive second-place finish, the party's inability to secure the presidency signaled the beginning of its unraveling. The immediate aftermath of the election revealed the fragility of the Progressive Party's coalition, which had been built on a diverse array of reformist ideals rather than a unified platform.

Several factors contributed to the party's dissolution. First, the absence of a clear legislative agenda beyond Roosevelt's New Nationalism made it difficult to sustain momentum. Second, the party lacked a robust organizational structure, relying heavily on Roosevelt's personal appeal. When he failed to win the presidency, many supporters questioned the party's viability. Third, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 shifted the nation's focus away from domestic reform, further marginalizing the Progressive Party's agenda. By 1916, the party's influence had waned significantly, and its candidates struggled to gain traction in local and national elections.

As the Progressive Party declined, its members faced a critical decision: remain loyal to a fading third party or rejoin the established Republican or Democratic Parties. Most chose the latter, driven by pragmatism and the desire to influence policy from within the two-party system. For instance, many Progressives who had left the Republican Party over Taft's conservatism returned, hoping to reshape the GOP from within. Others joined the Democratic Party, attracted by Wilson's reformist agenda, including the Federal Reserve Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act. This migration of members effectively dismantled the Progressive Party, as it lost both its base and its raison d'être.

The dissolution of the Progressive Party offers a cautionary tale for third-party movements. While they can catalyze change by pushing major parties to adopt their ideas, they often struggle to sustain themselves without a clear path to power. The Progressive Party's legacy, however, endures in the reforms it championed, such as direct primaries, women's suffrage, and antitrust legislation. For modern third-party advocates, the lesson is clear: to avoid dissolution, focus on building a durable coalition, crafting a cohesive platform, and securing incremental victories that demonstrate the party's relevance. Otherwise, the fate of the Bull Moose Party may repeat itself.

South Africa's Political Party Presidency: Strategies, Power, and Governance Explained

You may want to see also

Legacy and Influence: Inspired future progressive movements and policies in U.S. politics

Theodore Roosevelt's foray into third-party politics with the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party, in 1912 was more than a fleeting moment in American political history. It was a catalyst for progressive reform that continues to shape U.S. politics. His platform, which included social justice, environmental conservation, and economic fairness, laid the groundwork for future movements that sought to challenge the status quo and advocate for the common good.

Consider the New Deal era under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a distant cousin of Theodore. Many of the policies implemented during this period, such as the establishment of Social Security, the minimum wage, and labor rights, echo Theodore Roosevelt's progressive ideals. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), for instance, was a direct descendant of Theodore's conservation efforts, employing young men in natural resource conservation work. This example illustrates how Theodore's vision transcended his time, influencing policies that addressed the needs of a changing nation.

To understand the depth of Theodore Roosevelt's influence, examine the modern progressive movement. Issues like income inequality, healthcare reform, and environmental protection are central to contemporary progressive platforms. The push for a $15 minimum wage, universal healthcare, and the Green New Deal are modern manifestations of the progressive ideals Theodore championed. These policies are not mere echoes of the past but evolved responses to persistent and emerging challenges, demonstrating the adaptability and resilience of Roosevelt's progressive legacy.

A practical takeaway for activists and policymakers is to study the strategic alliances Theodore Roosevelt forged. He brought together labor unions, farmers, and urban reformers, creating a broad coalition that amplified the impact of his progressive agenda. Today, building diverse coalitions remains crucial for advancing progressive policies. For instance, the success of recent climate legislation has hinged on alliances between environmental groups, labor unions, and social justice organizations. By emulating Roosevelt's coalition-building approach, modern progressives can enhance their effectiveness and broaden their appeal.

Finally, Theodore Roosevelt's legacy serves as a reminder of the importance of bold leadership in driving progressive change. His willingness to challenge entrenched interests and advocate for systemic reform inspired generations of leaders. For those seeking to influence policy today, the lesson is clear: incrementalism has its place, but transformative change often requires bold vision and unwavering commitment. Whether advocating for healthcare reform, environmental justice, or economic fairness, drawing on Roosevelt's example can provide both inspiration and a strategic framework for achieving lasting impact.

Zelensky's Political Party Ban: Ukraine's Controversial Decision Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Theodore Roosevelt was a member of the Progressive Party, also known as the "Bull Moose Party," which he co-founded in 1912.

Theodore Roosevelt joined the Progressive Party after a split with the Republican Party over policy differences, particularly his progressive reform agenda, which was not fully supported by the Republican establishment.

Yes, Theodore Roosevelt ran for president in the 1912 election as the candidate of the Progressive Party, finishing second behind Democrat Woodrow Wilson and ahead of Republican William Howard Taft.

![Theodore Roosevelt'S Confession of Faith before the Progressive National Convention, August 6, 1912. 1912 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)