The election of 1860 was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Amidst this contentious backdrop, the Republican Party emerged victorious, with Abraham Lincoln securing the presidency. Lincoln's win was significant as it signaled a shift in national politics, as the Republicans, a relatively new party, had campaigned on a platform opposing the expansion of slavery into new territories. The election results exacerbated regional tensions, particularly in the South, where many viewed Lincoln's victory as a direct threat to their way of life, ultimately contributing to the secession of Southern states and the outbreak of the Civil War.

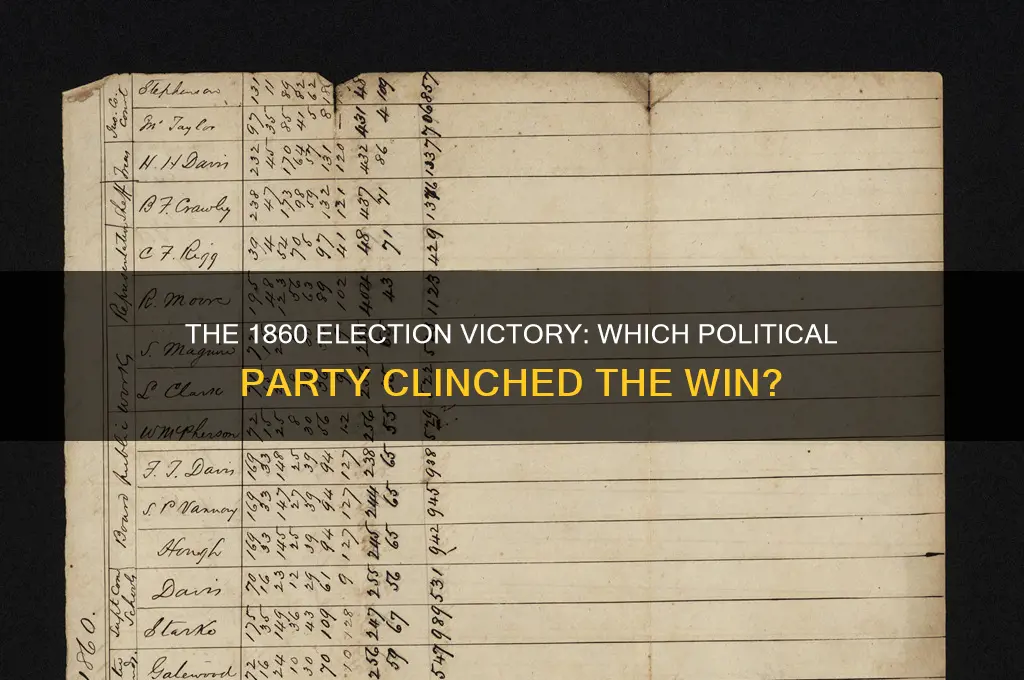

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Winning Political Party | Republican Party |

| Presidential Candidate | Abraham Lincoln |

| Vice Presidential Candidate | Hannibal Hamlin |

| Popular Vote | 1,865,908 (39.8% of total votes) |

| Electoral Votes | 180 |

| Main Opponent | Stephen A. Douglas (Democratic Party) |

| Key Campaign Issues | Opposition to the expansion of slavery, preservation of the Union |

| Historical Significance | Lincoln's victory led to the secession of Southern states and the Civil War |

| Election Date | November 6, 1860 |

| Inauguration Date | March 4, 1861 |

| Term in Office | 1861–1865 (Assassinated in 1865) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Abraham Lincoln’s Victory: Lincoln won as the Republican Party candidate in the 1860 election

- Democratic Party Split: Democrats divided into Northern and Southern factions, weakening their candidacy

- Constitutional Union Party: Formed by former Whigs and Know-Nothings, they aimed to avoid secession

- Southern Reaction: Southern states viewed Lincoln’s win as a threat, leading to secession

- Electoral College Results: Lincoln secured 180 electoral votes, winning without Southern support

Abraham Lincoln’s Victory: Lincoln won as the Republican Party candidate in the 1860 election

The 1860 U.S. presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Amidst this turmoil, Abraham Lincoln emerged victorious as the candidate of the Republican Party, a relatively young political force at the time. Lincoln's win was not just a personal triumph but a significant shift in the nation's political landscape, setting the stage for the Civil War and the eventual abolition of slavery.

The Republican Platform and Lincoln's Appeal

The Republican Party, founded in 1854, had risen to prominence on a platform opposing the expansion of slavery into new territories. Lincoln, a skilled orator and seasoned politician, embodied the party’s ideals without explicitly calling for the immediate abolition of slavery. His moderate stance appealed to Northern voters who sought to limit slavery’s reach while avoiding radical change. Lincoln’s debates with Stephen A. Douglas during the 1858 Senate campaign had already established him as a formidable figure, and his 1860 campaign capitalized on this reputation.

A Fractured Opposition

Lincoln’s victory was as much about Republican unity as it was about Democratic disarray. The Democratic Party, deeply divided over slavery, fielded two candidates: Stephen A. Douglas (Northern Democrats) and John C. Breckinridge (Southern Democrats). This split diluted the Democratic vote, allowing Lincoln to win the Electoral College with just 39.8% of the popular vote. Additionally, John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party further fragmented the opposition, appealing to moderate Southerners who opposed secession.

Regional Dynamics and Electoral Strategy

Lincoln’s path to victory relied on a strong Northern base. He swept the Northern states, securing 180 electoral votes without winning a single Southern state. This regional polarization underscored the growing divide between North and South. The Republican Party’s focus on economic modernization, such as tariffs and internal improvements, resonated with Northern industrialists and farmers, while its anti-slavery stance galvanized abolitionists.

The Aftermath: A Nation on the Brink

Lincoln’s election triggered immediate consequences. South Carolina seceded from the Union just weeks after the election, followed by six other Southern states before his inauguration. Lincoln’s victory thus became a catalyst for the Civil War, as the South viewed his presidency as a direct threat to their way of life. His administration would face the monumental task of preserving the Union while addressing the moral and constitutional questions surrounding slavery.

Practical Takeaway: Understanding Historical Context

For educators or history enthusiasts, Lincoln’s 1860 victory illustrates the power of political strategy and the dangers of ideological division. Analyzing this election offers insights into how regional interests, party platforms, and candidate personalities shape electoral outcomes. It also serves as a reminder of how political decisions can have far-reaching, transformative consequences. To deepen understanding, explore primary sources like Lincoln’s speeches or contemporary newspapers to grasp the era’s complexities.

Why We Hate Politics: A Critical Review of Public Discontent

You may want to see also

Democratic Party Split: Democrats divided into Northern and Southern factions, weakening their candidacy

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. A critical factor in the outcome was the Democratic Party’s internal fracture. Northern Democrats, who leaned toward compromise on slavery to preserve the Union, clashed with Southern Democrats, who demanded federal protection of slavery in all territories. This ideological rift led to a disastrous split at the party’s convention, where Southern delegates walked out after failing to secure a pro-slavery platform. The result? Two separate Democratic candidates: Stephen A. Douglas in the North and John C. Breckinridge in the South. This division fatally weakened the party’s electoral strength, paving the way for Abraham Lincoln’s victory with only 39.8% of the popular vote.

Consider the mechanics of this split as a cautionary tale in coalition-building. A party’s unity hinges on its ability to balance competing interests within its base. In 1860, the Democrats failed to negotiate a middle ground on slavery, a polarizing issue that directly threatened Southern economic interests. Northern Democrats’ willingness to entertain restrictions on slavery’s expansion alienated their Southern counterparts, who viewed such compromises as existential threats. This breakdown in communication and mutual understanding illustrates how internal ideological rigidity can fracture even the most established organizations. For modern political strategists, the lesson is clear: prioritize dialogue and compromise over purity tests, especially when core values are at stake.

To understand the electoral consequences, examine the numbers. In 1856, Democrat James Buchanan won with 45.3% of the popular vote and 174 electoral votes. Four years later, Douglas and Breckinridge combined for 47.6% of the popular vote but secured only 12 electoral votes. The split candidacy fragmented Democratic support, allowing Lincoln to win despite minimal Southern backing. This outcome underscores the mathematical reality of divided parties: even a slight internal fracture can redistribute power to opponents. For contemporary parties, this serves as a reminder that unity is not just a moral imperative but a strategic necessity, particularly in winner-take-all electoral systems.

Finally, the Democratic split of 1860 offers a historical lens for analyzing modern political fractures. Today’s parties often face similar challenges in balancing diverse factions. For instance, debates over climate policy, immigration, or healthcare can create internal tensions akin to the slavery divide of the 1860s. The key difference lies in how leaders manage these disagreements. Unlike the Democrats of 1860, successful modern parties employ mechanisms like caucuses, policy committees, and backroom negotiations to forge consensus. By studying this historical failure, current political actors can develop strategies to bridge divides, ensuring their party remains a viable contender rather than a cautionary example.

Is Political Party Affiliation Public Record in California?

You may want to see also

Constitutional Union Party: Formed by former Whigs and Know-Nothings, they aimed to avoid secession

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Amidst this turmoil, the Constitutional Union Party emerged as a unique political force, formed by former Whigs and Know-Nothings who sought to preserve the Union by avoiding the contentious issue of secession. Their platform was simple yet ambitious: uphold the Constitution and maintain national unity at all costs.

Analytically, the Constitutional Union Party’s strategy was a gamble. By refusing to take a firm stance on slavery, they aimed to appeal to moderate voters in both the North and South. Their candidate, John Bell, a former Whig senator from Tennessee, embodied this approach. However, this neutrality proved to be both their strength and their weakness. While it attracted Southerners wary of secession and Northerners opposed to radical abolitionism, it also alienated voters seeking clear solutions to the nation’s crises. The party’s inability to win a single electoral vote in the 1860 election underscores the limitations of their middle-ground strategy in a polarized political climate.

Instructively, the Constitutional Union Party’s formation offers a lesson in political coalition-building. To replicate their approach in modern contexts, one might:

- Identify a unifying principle (e.g., adherence to a shared document or value).

- Recruit diverse factions by emphasizing common ground over differences.

- Focus on procedural solutions rather than divisive policy specifics.

However, caution is necessary: avoiding contentious issues can lead to irrelevance, as demonstrated by the party’s failure to prevent secession or win the election.

Persuasively, the Constitutional Union Party’s legacy challenges the notion that political success requires ideological purity. In an era dominated by the Republican Party’s victory under Abraham Lincoln and the Southern Democrats’ push for secession, the Constitutional Unionists represented a third way—a plea for pragmatism over passion. Their message resonates today in debates where polarization often overshadows compromise. While their effort ultimately failed, it remains a reminder that unity, even if fleeting, is worth pursuing.

Comparatively, the Constitutional Union Party’s approach contrasts sharply with the strategies of their contemporaries. Unlike the Republicans, who championed abolition, or the Southern Democrats, who advocated secession, the Constitutional Unionists prioritized process over policy. This distinction highlights the trade-offs between principled stands and pragmatic unity. While their opponents left a more enduring mark on history, the Constitutional Unionists’ attempt to bridge divides offers a counterpoint to the rigidity of their rivals.

Descriptively, the Constitutional Union Party’s campaign was a study in restraint. Their slogan, “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was,” encapsulated their commitment to stability. Rallies and speeches focused on the sanctity of the Constitution and the dangers of disunion, avoiding the inflammatory rhetoric of the time. Yet, this measured tone could not compete with the urgency of the slavery debate. In a nation on the brink of war, their call for calm was drowned out by louder, more decisive voices. Their story is a poignant reminder of the challenges faced by moderates in times of crisis.

Understanding Political Parties: Roles, Functions, and Impact on Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.64 $29

Southern Reaction: Southern states viewed Lincoln’s win as a threat, leading to secession

The 1860 presidential election marked a seismic shift in American politics, with Abraham Lincoln’s victory as the Republican candidate triggering a chain reaction of fear and defiance in the South. Lincoln’s platform, which opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, was perceived by Southern leaders as a direct assault on their economic and social systems. This perception was not merely a political disagreement but a deeply existential threat, as slavery was the backbone of the Southern economy and a cornerstone of their way of life. The election results, therefore, were not just a transfer of power but a catalyst for secession, as Southern states began to view their place within the Union as untenable.

To understand the Southern reaction, consider the context: the South’s economy was heavily dependent on enslaved labor, particularly in agriculture. Cotton, produced by enslaved workers, accounted for over half of the nation’s exports. Lincoln’s election signaled a federal government no longer willing to protect or expand this system, leaving Southern elites convinced that their economic survival was at stake. South Carolina, the first state to secede in December 1860, issued a Declaration of the Immediate Causes, explicitly citing the "increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery" as justification. This was not an isolated sentiment; it was a widespread belief that Lincoln’s presidency would lead to the eventual abolition of slavery, prompting other Southern states to follow suit.

The secession movement was not merely a spontaneous reaction but a calculated strategy rooted in decades of growing sectional tensions. Southern leaders had long feared Northern dominance in federal politics and had fought to protect their interests through compromises like the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision. Lincoln’s election, however, shattered the illusion that these compromises could sustain the status quo. The Republican Party’s rise, with its explicit anti-slavery stance, represented a fundamental realignment of political power. For Southern states, secession became a preemptive strike to preserve their autonomy and way of life, even if it meant dismantling the Union.

Practically, the secession process was both swift and methodical. Between December 1860 and February 1861, seven states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—withdrew from the Union. They formed the Confederate States of America, electing Jefferson Davis as their president. This was not a decision made lightly; it involved mobilizing militias, seizing federal property, and preparing for potential conflict. The South’s reaction was not just ideological but logistical, as they sought to establish a new nation built on the preservation of slavery. This bold move set the stage for the Civil War, a conflict that would redefine the United States and the institution of slavery forever.

In retrospect, the Southern reaction to Lincoln’s victory was a tragic miscalculation driven by fear and a refusal to adapt to changing political realities. While secessionists believed they were protecting their interests, their actions ultimately led to the destruction of the Confederacy and the abolition of slavery. The election of 1860, therefore, was not just a political event but a turning point in American history, revealing the deep fractures within the nation and the lengths to which some would go to defend a morally bankrupt system. Understanding this reaction offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of prioritizing division over compromise and the enduring consequences of such choices.

How Political Parties Shape Congress: Influence, Power, and Legislation

You may want to see also

Electoral College Results: Lincoln secured 180 electoral votes, winning without Southern support

The 1860 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep regional divisions and the rise of Abraham Lincoln. A striking detail emerges from the Electoral College results: Lincoln secured 180 electoral votes, a decisive victory achieved entirely without Southern support. This outcome underscores the North’s consolidation behind the Republican Party and the South’s vehement rejection of Lincoln’s platform, particularly his opposition to the expansion of slavery.

Analyzing the electoral map reveals a stark divide. Lincoln swept the Northern states, winning every one except New Jersey, which split its votes. In contrast, Southern states uniformly rejected him, with not a single electoral vote cast in his favor. This regional polarization was a harbinger of the secession crisis that followed. The election effectively demonstrated that the Union was already fracturing along ideological and economic lines, with the North and South increasingly viewing their futures as incompatible.

From a strategic perspective, Lincoln’s victory highlights the importance of coalition-building within a fragmented political landscape. The Republican Party focused on mobilizing Northern voters, leveraging anti-slavery sentiment and economic interests tied to industrialization. Meanwhile, the South’s refusal to support Lincoln reflected its commitment to preserving slavery and states’ rights. This dynamic illustrates how electoral success can hinge on appealing to specific regional or ideological blocs, even at the cost of alienating others.

Practically, the 1860 election serves as a cautionary tale for modern politics. When a candidate wins without broad geographic support, it can exacerbate divisions and destabilize the nation. For those studying electoral strategies, the lesson is clear: while securing a majority is essential, fostering unity across diverse regions is equally critical. Ignoring significant portions of the electorate risks deepening rifts that may outlast any single election.

In conclusion, Lincoln’s 180 electoral votes, secured entirely without Southern support, were both a triumph and a warning. They signaled the North’s commitment to change but also exposed the fragility of the Union. This result remains a powerful reminder of how elections can reflect—and intensify—the fault lines within a society. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for anyone seeking to navigate the complexities of political campaigns or the consequences of polarization.

Unveiling Political Corruption: Whistleblowers and Activists Who Exposed the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party won the election of 1860.

Abraham Lincoln was the Republican candidate who won the 1860 presidential election.

Yes, the Democratic Party lost the 1860 election, as it was divided and ran two separate candidates.

The Republican Party won 180 electoral votes in the 1860 election.

The 1860 election was significant because it marked the first time the Republican Party won the presidency, and it led to the secession of Southern states, triggering the Civil War.