President William Howard Taft, who served as the 27th President of the United States from 1909 to 1913, was a member of the Republican Party. Taft’s political career was deeply rooted in Republican politics, as he had previously served as Secretary of War under President Theodore Roosevelt, a fellow Republican. His presidency continued many of the progressive policies initiated by Roosevelt, though Taft’s approach often differed, leading to tensions within the party. Despite his affiliation, Taft’s time in office was marked by challenges, including disputes over tariffs and antitrust policies, which ultimately contributed to his defeat in the 1912 election. His legacy remains tied to his Republican identity and his role in shaping early 20th-century American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Republican |

| President | William Howard Taft |

| Term in Office | 1909-1913 |

| Vice President | James S. Sherman (1909-1912), None (1912-1913) |

| Key Achievements | Established the Federal Reserve System, supported the 16th Amendment (federal income tax), promoted antitrust legislation |

| Notable Events | Payne-Aldrich Tariff, Ballinger-Pinchot Affair, breakup of Standard Oil and American Tobacco |

| Political Ideology | Progressive conservatism, supported trust-busting and regulation |

| Relationship with Theodore Roosevelt | Initially close, later strained due to policy differences |

| Post-Presidency | Served as Chief Justice of the United States (1921-1930) |

| Legacy | Only person to serve as both President and Chief Justice of the United States |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Taft's Party Affiliation: William Howard Taft was a member of the Republican Party

- Election: Taft won the presidency as the Republican nominee

- Progressive Split: Taft's policies led to a split with Progressive Republicans

- Post-Presidency: Taft later supported the Progressive Party briefly

- Chief Justice Role: Taft became Chief Justice, remaining politically unaffiliated in that role

Taft's Party Affiliation: William Howard Taft was a member of the Republican Party

William Howard Taft’s political identity was firmly rooted in the Republican Party, a fact that shaped his presidency and legacy. Elected as the 27th President of the United States in 1908, Taft succeeded Theodore Roosevelt, another Republican, and carried forward many of the party’s progressive ideals. His affiliation was not merely a label but a guiding force in his policies, which aimed to balance conservative fiscal principles with progressive reforms. Taft’s commitment to the Republican Party was evident in his efforts to lower tariffs, break up monopolies, and improve antitrust laws, all of which aligned with the party’s platform at the time.

To understand Taft’s party affiliation, consider the historical context of the early 20th century. The Republican Party was undergoing a transformation, with progressive and conservative factions vying for influence. Taft, often seen as a bridge between these groups, sought to unite the party while advancing its agenda. For instance, his support for the Federal Income Tax, established by the 16th Amendment during his presidency, reflected the party’s evolving stance on fiscal policy. This pragmatic approach, however, sometimes alienated more radical progressives, highlighting the complexities of his party loyalty.

A practical takeaway from Taft’s Republican affiliation is the importance of understanding a leader’s party ties in predicting their governance. For educators or students studying U.S. history, examining Taft’s policies through the lens of his party membership provides insight into the era’s political dynamics. For example, his antitrust actions, such as the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911, were consistent with the Republican Party’s commitment to fair competition, a principle still relevant in today’s discussions on corporate regulation.

Comparatively, Taft’s party loyalty contrasts with some modern politicians who shift affiliations or adopt independent stances. His steadfast commitment to the Republican Party, even when it led to tensions within his own administration, underscores the value of ideological consistency in leadership. This example serves as a cautionary tale for aspiring politicians: while party affiliation can provide a platform, it also demands alignment with its principles, even when doing so proves challenging.

Finally, Taft’s Republican identity offers a lens for analyzing contemporary political landscapes. In an age of polarization, his ability to navigate party divisions—albeit with mixed success—provides a historical benchmark for bipartisan cooperation. For those interested in political strategy, studying Taft’s approach reveals the delicate balance between adhering to party doctrine and pursuing pragmatic governance. His legacy reminds us that party affiliation is not just a label but a framework for action, one that can either unite or divide depending on how it is wielded.

MJ's Political Stance: Uncovering His Views and Activism

You may want to see also

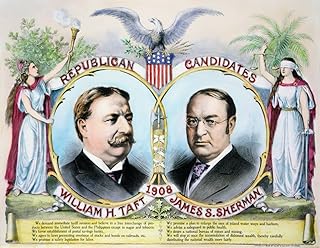

1908 Election: Taft won the presidency as the Republican nominee

The 1908 U.S. presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, solidifying the Republican Party’s dominance during the Progressive Era. William Howard Taft, handpicked by outgoing President Theodore Roosevelt, emerged as the Republican nominee, embodying continuity with Roosevelt’s policies while offering a more conservative approach. Taft’s victory over Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan—Bryan’s third and final presidential bid—highlighted the GOP’s strength in an era of economic growth and reform. This election underscored the Republican Party’s ability to balance progressive ideals with traditional conservatism, a strategy that resonated with voters.

Taft’s campaign leaned heavily on his reputation as a competent administrator and legal mind, having served as Roosevelt’s Secretary of War and a federal judge. His platform emphasized antitrust enforcement, tariff reform, and continued trust-busting, aligning with Roosevelt’s progressive agenda. However, Taft’s style differed from Roosevelt’s charismatic leadership; he favored deliberation over drama, a trait that both reassured and alienated segments of the electorate. The Republican Party’s machinery, coupled with Taft’s promise to uphold Roosevelt’s legacy, proved decisive in securing his victory.

A comparative analysis of the 1908 election reveals the GOP’s strategic advantage. While Bryan’s populist rhetoric appealed to agrarian and labor interests, his opposition to imperialism and his shifting stance on monetary policy (bimetallism) limited his appeal in an increasingly industrialized nation. Taft, by contrast, positioned himself as a unifier, appealing to both progressive Republicans and conservative business interests. The Republican Party’s ability to bridge these factions was a key factor in Taft’s landslide win, capturing 321 electoral votes to Bryan’s 162.

Practically, Taft’s presidency began with high expectations, but his tenure would later expose fractures within the Republican Party. His focus on antitrust litigation, such as the breakup of Standard Oil, initially aligned with progressive goals. However, his support for the Payne-Aldrich Tariff and perceived lack of enthusiasm for progressive reforms alienated Roosevelt and fueled the eventual split between progressive and conservative Republicans. This tension set the stage for the 1912 election, where the GOP’s unity would unravel.

In retrospect, the 1908 election serves as a case study in political succession and party dynamics. Taft’s victory demonstrated the Republican Party’s adaptability in an era of change, but also foreshadowed its internal divisions. For modern observers, the election offers a lesson in the challenges of balancing diverse party interests and the risks of over-relying on a predecessor’s legacy. Taft’s presidency, while rooted in Republican principles, ultimately became a turning point that reshaped the party’s trajectory.

Exploring Diverse Careers: Where Political Scientists Work and Thrive

You may want to see also

Progressive Split: Taft's policies led to a split with Progressive Republicans

William Howard Taft, the 27th President of the United States, was a member of the Republican Party. However, his presidency marked a significant turning point within the party, particularly among its Progressive faction. Taft’s policies and leadership style clashed with the ideals of Progressive Republicans, ultimately leading to a deep and lasting split. This division was not merely ideological but had tangible consequences for the party’s unity and electoral success.

To understand the split, consider Taft’s approach to key issues such as antitrust legislation and conservation. While Progressive Republicans, led by figures like Theodore Roosevelt, advocated for aggressive trust-busting and environmental protection, Taft pursued a more conservative and legalistic approach. For instance, his administration’s lawsuit against U.S. Steel in 1911, which sought to dissolve the company, was seen by Progressives as a half-hearted effort. Roosevelt had previously allowed the company to form, but Taft’s decision to challenge it was viewed as politically motivated rather than a genuine commitment to breaking up monopolies. This discrepancy in priorities alienated Progressive Republicans, who felt Taft was undermining their reformist agenda.

The tension escalated during the 1912 presidential election, a pivotal moment in the Progressive split. Frustrated with Taft’s leadership, Theodore Roosevelt challenged him for the Republican nomination. When Taft secured the nomination, Roosevelt and his supporters broke away to form the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party. This fracture not only weakened the Republican Party but also ensured the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson, as the Republican vote was split between Taft and Roosevelt. The election results underscored the depth of the divide: Roosevelt won more votes than Taft, highlighting the strength of the Progressive faction and the extent of their disillusionment with Taft’s policies.

Analyzing this split reveals a broader lesson about party cohesion and leadership. Taft’s inability to bridge the gap between traditional Republicans and Progressive reformers demonstrates the risks of ignoring internal factions. His focus on judicial solutions and incremental change failed to satisfy the urgent demands of Progressives, who sought bold, transformative policies. This misalignment not only led to the temporary fragmentation of the Republican Party but also reshaped the political landscape, paving the way for the Democratic Party’s dominance in the subsequent decades.

In practical terms, the Taft-Progressive split offers a cautionary tale for modern political leaders. Balancing diverse factions within a party requires more than compromise; it demands a clear vision that aligns with the core values of all groups. For those studying political strategy, the episode underscores the importance of understanding constituent priorities and communicating policies in ways that resonate across ideological lines. By examining this historical split, one can glean insights into the delicate art of maintaining party unity in the face of competing interests.

Where's the Beef in Politics? Uncovering Empty Promises and Policy Substance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Post-Presidency: Taft later supported the Progressive Party briefly

William Howard Taft's post-presidency political journey is a fascinating study in ideological evolution and the fluidity of party loyalties. After his presidency, Taft, initially a stalwart Republican, found himself drawn to the Progressive Party, albeit briefly. This shift was not merely a casual flirtation with a new political movement but a calculated alignment with principles he had begun to champion during his time on the Supreme Court. Taft's support for the Progressive Party, led by his former political rival Theodore Roosevelt, underscores the complexity of his political identity and the broader ideological shifts within early 20th-century American politics.

To understand Taft's brief alignment with the Progressive Party, consider the context of his post-presidential career. Appointed Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court by President Warren G. Harding in 1921, Taft had already transitioned from executive to judicial leadership. However, his judicial role did not silence his political voice. Taft's endorsement of the Progressive Party in 1914, following his presidential defeat in 1912, was rooted in his growing support for antitrust measures, labor rights, and government reform—core tenets of the Progressive agenda. This move was less about abandoning the Republican Party and more about advancing specific policy goals he believed were critical for the nation's future.

Taft's support for the Progressive Party was strategic rather than absolute. He did not formally switch parties, nor did he run for office under the Progressive banner. Instead, he lent his influence to the party's platform, particularly its emphasis on judicial efficiency and social welfare. For instance, Taft advocated for the creation of a federal trade commission and supported the direct election of senators, both Progressive priorities. His endorsement was a pragmatic attempt to push the Republican Party toward reform, rather than a wholesale rejection of his political roots. This nuanced approach reflects Taft's belief in incremental change within the existing two-party system.

A comparative analysis of Taft's post-presidency actions reveals a stark contrast to other former presidents. Unlike figures such as John Quincy Adams, who returned to Congress after leaving office, Taft's influence was primarily judicial and ideological. His brief alignment with the Progressive Party highlights the unique role former presidents can play in shaping political discourse without seeking elective office. Taft's actions also illustrate the challenges of maintaining party loyalty in an era of rapid political transformation. While his support for the Progressive Party was short-lived, it left a lasting imprint on his legacy, positioning him as a bridge between traditional Republicanism and progressive reform.

In practical terms, Taft's post-presidency engagement offers a blueprint for former leaders seeking to remain politically relevant. By focusing on specific issues rather than partisan loyalty, Taft demonstrated how to leverage influence effectively. For those interested in political activism post-office, Taft's example suggests aligning with movements that reflect one's core values, even if it means crossing party lines. His story is a reminder that political identities are not static and that principled flexibility can drive meaningful change. Whether you're a former leader or an engaged citizen, Taft's brief but impactful support for the Progressive Party underscores the importance of staying true to one's convictions in a dynamic political landscape.

Why Obama Chose Politics: Uncovering His Motivations and Journey

You may want to see also

Chief Justice Role: Taft became Chief Justice, remaining politically unaffiliated in that role

William Howard Taft, the 27th President of the United States, was a member of the Republican Party during his presidency. However, his political journey took a unique turn when he later became the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. This transition highlights a critical aspect of the Chief Justice role: the necessity of political impartiality. Once appointed, Taft consciously shed his partisan affiliations, embodying the judiciary’s commitment to fairness and objectivity. This shift underscores the distinct nature of the Chief Justice position, which demands a departure from political loyalties to uphold the integrity of the legal system.

To understand Taft’s transformation, consider the practical steps he took to distance himself from politics. Upon assuming the Chief Justice role in 1921, Taft ceased participating in partisan activities and publicly declared his commitment to judicial independence. For instance, he avoided endorsing political candidates or commenting on party platforms, a stark contrast to his earlier years as a Republican stalwart. This deliberate detachment serves as a model for how judicial leaders can navigate the transition from political office to the bench. For anyone in a leadership role, this example illustrates the importance of prioritizing institutional integrity over personal or partisan interests.

A comparative analysis of Taft’s dual roles reveals the inherent tension between political leadership and judicial impartiality. As President, Taft’s decisions were often shaped by Republican Party priorities, such as antitrust enforcement and tariff reform. However, as Chief Justice, his rulings were guided by constitutional principles rather than partisan agendas. This contrast highlights the judiciary’s role as a non-partisan arbiter of law, distinct from the inherently political nature of the executive branch. For those studying governance, Taft’s career offers a case study in the separation of powers and the ethical boundaries of each branch.

Persuasively, Taft’s ability to remain politically unaffiliated as Chief Justice strengthens the public’s trust in the judiciary. In an era of increasing political polarization, his example reminds us that the law must transcend party lines. Practical tips for maintaining impartiality include establishing clear boundaries between personal beliefs and professional duties, as Taft did. For judges, lawyers, or even corporate leaders, this means avoiding situations that could compromise perceived fairness. Taft’s legacy demonstrates that true leadership often requires setting aside personal or political allegiances for the greater good.

Finally, Taft’s tenure as Chief Justice provides a descriptive snapshot of how judicial leadership can shape institutional culture. He focused on administrative reforms, such as improving the Court’s efficiency and advocating for the Judiciary Act of 1925, which reduced the Court’s workload. These efforts, untainted by political bias, solidified his reputation as a transformative figure in American jurisprudence. His story serves as a guide for anyone seeking to lead with integrity, emphasizing that the most impactful roles often require leaving personal agendas behind. By studying Taft’s transition, we gain actionable insights into the art of impartial leadership.

Is Political Party Affiliation a Continuous Variable? Exploring the Spectrum

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

President William Howard Taft was affiliated with the Republican Party.

President Taft ran for office as a Republican, winning the presidency in the 1908 election.

Yes, President Taft was a Republican, the same party as his predecessor, President Theodore Roosevelt.

Yes, after his presidency, Taft later supported the Democratic Party and endorsed Democratic candidates, though he never formally switched his party affiliation.

The Republican Party nominated William Howard Taft as their candidate for the 1908 presidential election.