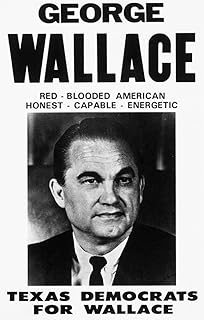

George Wallace, a prominent and controversial figure in American politics, was primarily associated with the Democratic Party during his early political career. Serving as the Governor of Alabama for four terms, Wallace became a symbol of segregationist policies and states' rights, famously declaring segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever in his 1963 inaugural address. Despite his deep ties to the Democratic Party, Wallace later ran for president multiple times, including as an independent in 1968 and as a Democrat in 1972, before briefly switching to the Republican Party in 1980 in an unsuccessful bid for the presidency. His political journey reflects the complex and evolving nature of American political affiliations during the mid-20th century.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Early Political Affiliation | Democratic Party |

| Governorships | Elected as Governor of Alabama (1963–1967, 1971–1979, 1983–1987) as a Democrat |

| 1968 Presidential Campaign | Ran as the candidate of the American Independent Party (third-party) |

| 1972 Presidential Campaign | Initially sought Democratic nomination, later ran as a Democrat in primaries |

| Ideological Stance | Known for segregationist policies and "states' rights" rhetoric |

| Later Political Affiliation | Remained a Democrat throughout his political career, despite third-party presidential runs |

| Legacy | Associated with the Democratic Party, but his views aligned with conservative Southern Democrats |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Early Political Career: Wallace started as a Democrat, initially supporting moderate policies before shifting rightward

- Presidential Campaign: Ran as an independent, advocating segregation and states' rights, winning five Southern states

- American Independent Party: Founded to support Wallace's 1968 campaign, emphasizing conservative populism and anti-establishment views

- Return to Democratic Party: Rejoined Democrats in 1975, moderating his views and seeking reconciliation in later campaigns

- Legacy and Impact: Wallace's party shifts reflect evolving Southern politics and the realignment of the Democratic Party

Early Political Career: Wallace started as a Democrat, initially supporting moderate policies before shifting rightward

George Wallace's early political career is a study in ideological transformation, marked by a notable shift from moderate Democratic policies to a more conservative stance. Initially, Wallace aligned himself with the Democratic Party, a decision that reflected the political landscape of the American South during the mid-20th century. At this stage, his views were characterized by a pragmatic approach to governance, focusing on issues like industrial development and education reform. This period of his career is often overlooked, yet it provides crucial context for understanding his later, more controversial positions.

To grasp Wallace's evolution, consider the political climate of Alabama in the 1950s. As a young state legislator and later as a circuit judge, he supported policies that were, by the standards of the time and place, relatively progressive. For instance, he refused to endorse the "Southern Manifesto," a document opposing racial integration in schools, and even spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan. These early stances were not radical by national standards but were significant within the deeply segregated South. Such positions suggest a politician attuned to the complexities of his constituency, willing to navigate the tensions between tradition and change.

However, Wallace's trajectory took a sharp turn during his first gubernatorial campaign in 1958, which he lost to a more segregationist candidate. This defeat served as a political awakening, leading him to adopt a more hardline stance on racial issues. The shift was strategic, aimed at appealing to the conservative base of the Democratic Party in Alabama. By the time he ran again in 1962, Wallace had fully embraced the rhetoric of states' rights and segregation, famously declaring in his inaugural address, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever." This marked the beginning of his transformation from a moderate Democrat to a symbol of Southern resistance to federal civil rights policies.

Understanding this transition requires examining the broader political and social forces at play. The Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum, and federal interventions, such as the Brown v. Board of Education decision, were challenging the status quo in the South. Wallace's shift rightward was not merely a personal evolution but a response to these external pressures. By aligning himself with the fears and frustrations of white Southerners, he secured a powerful political base that would sustain his career for decades.

In retrospect, Wallace's early career as a moderate Democrat offers valuable insights into the fluidity of political identities and the influence of context on ideology. His initial support for pragmatic, centrist policies contrasts sharply with his later reputation as a staunch segregationist. This duality highlights the complexities of political adaptation and the ways in which leaders can reshape their beliefs to align with shifting electoral landscapes. For those studying political strategy or the history of the American South, Wallace's early years serve as a cautionary tale about the potential for ideological drift in response to political expediency.

How to Form a Political Party in Florida: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

1968 Presidential Campaign: Ran as an independent, advocating segregation and states' rights, winning five Southern states

George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign stands as a stark example of how regional grievances and divisive rhetoric can resonate in a fractured political landscape. Running as an independent candidate, Wallace championed a platform rooted in segregation and states' rights, tapping into the anxieties of a South resistant to federal intervention in racial matters. His campaign was not merely a symbolic gesture but a calculated strategy to exploit the tensions between national progressivism and local autonomy. By framing his candidacy as a defense of Southern heritage and sovereignty, Wallace successfully mobilized a coalition of voters who felt alienated by the mainstream parties.

Wallace's appeal was both ideological and emotional, leveraging the cultural and racial fears of the time. His rhetoric often invoked the specter of federal overreach, painting a picture of a distant government imposing its will on local communities. This narrative resonated particularly in the Deep South, where memories of Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement had left a legacy of resentment toward federal authority. Wallace's ability to articulate these sentiments in a compelling, if inflammatory, manner allowed him to win five Southern states—Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi—and secure 46 electoral votes. This outcome underscored the enduring power of regional identity in American politics.

Analytically, Wallace's campaign reveals the limitations of the two-party system in addressing deep-seated regional and ideological divides. By running as an independent, he circumvented the constraints of party platforms and appealed directly to voters who felt unrepresented by either the Democrats or Republicans. His success also highlights the strategic use of wedge issues in political campaigns. Segregation and states' rights were not just policy positions for Wallace; they were tools to galvanize a base and differentiate himself from his opponents. This approach, while effective in the short term, had long-term consequences, further polarizing the nation along racial and regional lines.

From a practical standpoint, Wallace's 1968 campaign offers lessons for modern politicians navigating complex electoral landscapes. It demonstrates the importance of understanding regional dynamics and tailoring messages to specific audiences. However, it also serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of exploiting division for political gain. While Wallace's strategy yielded immediate results, it contributed to a legacy of racial and political polarization that continues to shape American politics. For those studying campaign strategies, Wallace's independent run underscores the potential impact of third-party or independent candidacies in disrupting traditional party dominance.

In conclusion, George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign as an independent candidate advocating segregation and states' rights was a pivotal moment in American political history. His success in winning five Southern states reflected the enduring strength of regional identity and resistance to federal authority. While his campaign was a tactical triumph, it also exposed the fragility of national unity in the face of divisive rhetoric. Understanding this chapter of history provides valuable insights into the complexities of American politics and the enduring challenges of balancing local autonomy with national progress.

Understanding the Sunbelt's Political Significance in Modern American Politics

You may want to see also

American Independent Party: Founded to support Wallace's 1968 campaign, emphasizing conservative populism and anti-establishment views

George Wallace, the fiery governor of Alabama, was a political maverick whose 1968 presidential campaign demanded a vehicle outside the two-party system. Enter the American Independent Party (AIP), a third-party creation explicitly founded to support Wallace’s bid for the presidency. This party wasn’t merely a platform for Wallace’s personal ambitions; it was a deliberate rejection of the establishment, both Democratic and Republican, which Wallace and his supporters viewed as out of touch with the concerns of ordinary Americans. The AIP’s formation marked a strategic effort to channel conservative populism, a movement characterized by its appeal to working-class voters disillusioned with the status quo.

The AIP’s platform mirrored Wallace’s own rhetoric, emphasizing states’ rights, law and order, and opposition to federal overreach. These themes resonated deeply in the South and among blue-collar workers in the North, who felt abandoned by the civil rights and social reforms of the 1960s. By framing itself as the anti-establishment alternative, the AIP sought to capitalize on widespread frustration with the Vietnam War, racial integration, and the perceived elitism of Washington. Wallace’s campaign, backed by the AIP, became a rallying cry for those who believed their voices were being silenced by the political elite.

However, the AIP’s success was both its strength and its limitation. While it successfully mobilized millions of voters—Wallace won 13.5% of the popular vote and 46 electoral votes—the party struggled to outlive its candidate. The AIP’s identity was so tightly bound to Wallace that it lacked a broader, sustainable vision. After 1968, the party floundered, eventually becoming a minor player in American politics, though it continued to exist in various forms. This raises a critical question: Can a third party built around a single figure ever transcend its origins and become a lasting force?

For those interested in political strategy, the AIP offers a cautionary tale. While it effectively harnessed conservative populism in the short term, its failure to evolve beyond Wallace’s persona underscores the challenges of single-issue or personality-driven parties. Practical advice for modern third-party organizers? Focus on building a coalition around shared principles rather than a single charismatic leader. The AIP’s legacy reminds us that anti-establishment sentiment alone, without a robust organizational structure and inclusive platform, is insufficient for long-term political relevance.

Ethics Exploited: How Political Parties Manipulate Voter Morality

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$29.95

Return to Democratic Party: Rejoined Democrats in 1975, moderating his views and seeking reconciliation in later campaigns

George Wallace's political journey was marked by a dramatic shift when he rejoined the Democratic Party in 1975, a move that signaled a significant moderation of his previously hardline stances. This return was not merely a bureaucratic change but a strategic realignment that reflected his evolving political philosophy. By the mid-1970s, Wallace had begun to distance himself from the segregationist rhetoric that defined his earlier career, instead focusing on populist economic issues and seeking to appeal to a broader, more diverse electorate. This pivot was both a response to the changing political landscape and a personal recalibration, as Wallace sought to redefine his legacy.

To understand the impact of this shift, consider the context of the era. The civil rights movement had achieved major legislative victories, and public opinion was increasingly intolerant of overt racism. Wallace’s earlier campaigns, which had leaned heavily on states' rights and segregationist appeals, were no longer politically viable. By rejoining the Democratic Party, Wallace positioned himself within the mainstream of American politics, allowing him to reframe his message around economic populism and anti-elitism. This strategic moderation was not just about survival; it was about relevance in a post-segregationist America.

A key aspect of Wallace’s return to the Democratic Party was his effort to seek reconciliation, particularly with African American voters. In his later campaigns, he made overtures to Black communities, acknowledging past mistakes and expressing a desire to move forward. For instance, during his 1982 gubernatorial campaign in Alabama, Wallace actively sought the support of Black voters, even appearing at historically Black colleges and universities. While these efforts were met with mixed reactions, they underscored a deliberate attempt to bridge divides and rebuild trust. This approach was not without its critics, who viewed it as politically expedient rather than genuinely transformative, but it marked a clear departure from his earlier stance.

Practical lessons can be drawn from Wallace’s moderation and reconciliation efforts. For politicians seeking to pivot from controversial positions, authenticity is crucial. Wallace’s success in later campaigns was partly due to his willingness to publicly acknowledge his past errors, a step that humanized him in the eyes of many voters. Additionally, focusing on tangible issues like economic inequality and healthcare allowed him to connect with a broader audience. For those in leadership roles, this underscores the importance of adaptability and the need to align with the values of the electorate, even if it means abandoning long-held positions.

In conclusion, George Wallace’s return to the Democratic Party in 1975 was more than a party switch; it was a calculated effort to moderate his views and seek reconciliation in a changing America. By refocusing his message and acknowledging past mistakes, he managed to extend his political career and leave a more nuanced legacy. This chapter of his journey offers valuable insights into the complexities of political reinvention and the power of strategic moderation in an evolving political landscape.

Understanding Socialist Political Economy: Principles, Practices, and Global Impact

You may want to see also

Legacy and Impact: Wallace's party shifts reflect evolving Southern politics and the realignment of the Democratic Party

George Wallace's political party shifts—from Democrat to American Independent Party candidate to Republican—mirror the seismic changes in Southern politics and the broader realignment of the Democratic Party during the 20th century. His journey encapsulates the South's transition from a solidly Democratic stronghold to a Republican bastion, driven by racial politics, economic shifts, and cultural divides. Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign as the American Independent Party candidate, built on segregationist rhetoric, exploited the growing rift between the Democratic Party's conservative Southern wing and its increasingly progressive national platform. This move highlighted how the South's resistance to civil rights reforms was reshaping party loyalties.

To understand Wallace's impact, consider the "Southern Strategy," a Republican tactic to appeal to white voters disillusioned with the Democratic Party's embrace of civil rights. Wallace's campaigns, particularly his 1968 run, acted as a trial run for this strategy, demonstrating the political viability of racial backlash. His ability to win five Southern states as a third-party candidate signaled to the GOP that the South was fertile ground for conservative, racially charged messaging. By the 1980s, when Wallace ran for governor as a Democrat again, the party's Southern base had already begun to fracture, with many conservative Democrats defecting to the Republican Party.

Wallace's legacy also underscores the Democratic Party's ideological realignment. His opposition to federal intervention in state affairs, particularly on racial issues, clashed with the national Democratic Party's growing commitment to civil rights and social justice. This tension forced the party to confront its internal contradictions, ultimately marginalizing its conservative Southern wing. Wallace's shift to the Republican Party in his final gubernatorial campaign in 1982 symbolized the completion of this realignment, as the South became increasingly Republican and the Democratic Party solidified its position as the party of liberalism.

Practical takeaways from Wallace's party shifts include the importance of understanding regional political dynamics. For instance, modern politicians can learn from how Wallace's ability to tap into local grievances—whether racial, economic, or cultural—shaped electoral outcomes. Additionally, his story serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of divisive politics, as his segregationist policies left a lasting scar on Alabama and the nation. To navigate today's polarized landscape, leaders must balance regional interests with national unity, avoiding the pitfalls of exploiting division for short-term gain.

In conclusion, George Wallace's party shifts were not just personal political maneuvers but reflections of deeper structural changes in American politics. His journey from Democrat to third-party candidate to Republican illustrates the South's political transformation and the Democratic Party's ideological evolution. By studying Wallace, we gain insight into how regional issues, racial politics, and party realignment intersect, offering lessons for addressing contemporary political challenges. His legacy reminds us that the choices of individual leaders can reshape the political landscape for generations.

How Political Parties Shape Legislation: Power, Influence, and Policy Outcomes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Wallace was primarily associated with the Democratic Party for most of his political career.

Yes, George Wallace ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1964, 1972, and 1976.

No, George Wallace was not a member of the Republican Party, though he did appeal to some conservative Republican voters during his campaigns.

Yes, in 1968, George Wallace ran for president as the candidate of the American Independent Party, a third-party movement.

George Wallace was a staunch segregationist, and his pro-segregation views were often at odds with the national Democratic Party's shift toward civil rights in the 1960s.

![Encyclopedia of the Kennedys: The People and Events That Shaped America [3 volumes]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/918nI+jqJrL._AC_UL320_.jpg)