George Orwell, the renowned author of *1984* and *Animal Farm*, was not formally affiliated with any political party, but his political beliefs were deeply rooted in democratic socialism and anti-totalitarianism. While he was a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) for a brief period in the 1930s, he later distanced himself from it due to its pacifist stance, which he found incompatible with his experiences fighting fascism during the Spanish Civil War. Orwell’s writings often critiqued both capitalism and authoritarian communism, advocating instead for a more equitable and democratic society. His political stance was shaped by his firsthand observations of inequality, imperialism, and the dangers of ideological extremism, making him a complex and independent thinker rather than a strict adherent to any single party.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Affiliation | George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair) was not formally a member of any political party, but he was closely associated with democratic socialism and was a staunch critic of totalitarianism. |

| Ideological Leanings | Democratic Socialism, Anti-Totalitarianism, Anti-Stalinism |

| Notable Works Reflecting Views | Animal Farm, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Homage to Catalonia |

| Political Activism | Fought in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side, aligned with the POUM (Workers' Party of Marxist Unification), a non-Stalinist communist party. |

| Criticisms | Criticized both capitalism and Soviet-style communism, emphasizing the importance of individual freedom and democratic principles. |

| Legacy | His writings continue to influence left-wing and libertarian thought, advocating for a democratic socialist society free from authoritarianism. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Orwell's Political Affiliation: He was a democratic socialist, not aligned with any specific political party

- Labour Party Sympathy: Orwell supported the Labour Party but was critical of its policies

- Independent Labour Party: He briefly joined the ILP, a left-wing socialist group

- Anti-Stalinism: Orwell opposed totalitarianism, including Stalinist communism

- Anarchist Influences: His views were shaped by anarchist ideas, though he never formally joined

Orwell's Political Affiliation: He was a democratic socialist, not aligned with any specific political party

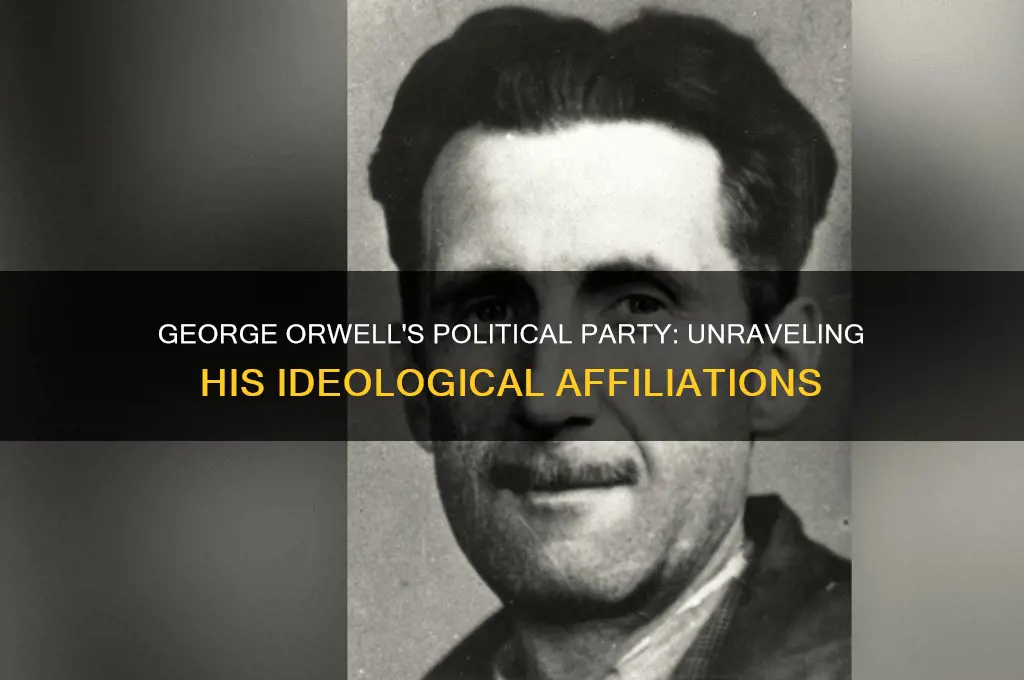

George Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair, is often associated with democratic socialism, a political philosophy that advocates for a democratically managed economy and society. However, it is crucial to note that Orwell was not formally aligned with any specific political party. This distinction is important because it highlights his independent and critical approach to politics, which often transcended party lines. Orwell’s writings, such as *Animal Farm* and *Nineteen Eighty-Four*, reflect his deep skepticism of authoritarianism and his commitment to social justice, values central to democratic socialism. Yet, his refusal to join a party underscores his belief in the importance of intellectual autonomy over ideological conformity.

To understand Orwell’s stance, consider his experiences during the Spanish Civil War, where he fought alongside the POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification), a leftist anti-Stalinist group. This period solidified his opposition to totalitarianism, whether from the right or left, and his belief in a democratic approach to socialism. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Orwell did not align with the Communist Party, which he viewed as corrupt and oppressive. Instead, he championed a vision of socialism rooted in equality, freedom, and grassroots democracy, principles he believed were betrayed by both capitalist exploitation and Stalinist authoritarianism.

Orwell’s democratic socialism was not merely theoretical; it was grounded in his lived experiences and observations. For instance, his time as a colonial officer in Burma exposed him to the injustices of imperialism, while his years living in poverty in London and Paris deepened his empathy for the working class. These experiences informed his critique of systemic inequality and his advocacy for a society where power and resources are distributed fairly. However, his refusal to join a party suggests he saw political organizations as prone to dogmatism and compromise, preferring instead to influence public discourse through his writing.

Practically speaking, Orwell’s approach offers a lesson in political engagement: it is possible to hold firm principles without becoming entrenched in partisan politics. For those inspired by his ideas, the takeaway is to prioritize values over labels. Advocate for policies that promote economic equality and democratic control, but remain vigilant against the dangers of ideological rigidity. Engage critically with political parties, recognizing that no single organization can fully embody the complexities of democratic socialism. Orwell’s legacy reminds us that true political commitment lies in the courage to think independently and act ethically, even when it means standing apart from the crowd.

In conclusion, Orwell’s democratic socialism was a deeply personal and intellectual commitment, unbound by party affiliation. His life and work demonstrate that political ideals are most powerful when they are lived and defended with integrity, rather than blindly followed. By embracing his example, individuals can navigate the complexities of modern politics with clarity and purpose, staying true to the principles of justice and freedom that Orwell held dear.

Politically Aware: Comparing Generations, Genders, and Socioeconomic Groups

You may want to see also

Labour Party Sympathy: Orwell supported the Labour Party but was critical of its policies

George Orwell, the pen name of Eric Arthur Blair, is often associated with a complex and nuanced political stance. While he is widely recognized for his critiques of totalitarianism in works like *1984* and *Animal Farm*, his relationship with the Labour Party is less straightforward. Orwell’s sympathy for the Labour Party was evident, but it was tempered by his sharp criticism of its policies and practices. This duality reflects his commitment to democratic socialism and his frustration with the party’s failures to fully embody its ideals.

Orwell’s support for the Labour Party stemmed from its alignment with his socialist principles. He believed in the party’s potential to address social inequality and empower the working class. For instance, in his essay *Why I Write* (1946), Orwell stated that every line of serious work he had written since the 1930s was “written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism.” This underscores his foundational belief in the Labour Party’s mission, which he saw as a bulwark against both fascism and unbridled capitalism. His experiences fighting in the Spanish Civil War alongside Marxist groups further solidified his commitment to leftist ideals, which the Labour Party nominally represented.

However, Orwell’s sympathy for the Labour Party was not blind. He was acutely critical of its policies, particularly its tendency to compromise socialist principles for political expediency. In *The Road to Wigan Pier* (1937), he lambasted the party’s leadership for failing to genuinely connect with the working class, whose interests they claimed to represent. Orwell argued that the Labour Party often prioritized maintaining power over implementing radical reforms, a critique that remains relevant today. His disillusionment was also evident in his disdain for the party’s bureaucratic tendencies, which he believed stifled grassroots activism and diluted its revolutionary potential.

Orwell’s critique extended to the Labour Party’s foreign policy, especially its stance during World War II. While he supported the war effort against Nazi Germany, he was critical of the party’s alliance with Stalin’s Soviet Union, which he viewed as another form of totalitarianism. This tension highlights Orwell’s intellectual honesty: he refused to let ideological loyalty overshadow his commitment to truth and justice. His essay *Second Thoughts on James Burnham* (1946) further illustrates his skepticism of the Labour Party’s ability to resist the allure of power and maintain its socialist integrity.

In practical terms, Orwell’s relationship with the Labour Party offers a lesson in critical engagement with political institutions. His approach suggests that supporting a party does not require unconditional loyalty; instead, it demands vigilance and a willingness to challenge its shortcomings. For those inspired by Orwell’s ideals, this means advocating for policies that genuinely serve the working class while holding the party accountable for its actions. Orwell’s legacy encourages us to remain skeptical, to question authority, and to strive for a socialism that is both principled and practical. His nuanced stance reminds us that true political commitment lies not in blind allegiance but in the relentless pursuit of justice and equality.

Exploring Panama's Political Landscape: Parties, Ideologies, and Influence

You may want to see also

Independent Labour Party: He briefly joined the ILP, a left-wing socialist group

George Orwell, the renowned author and political commentator, had a complex relationship with political parties, often aligning himself with socialist ideals. Among his various affiliations, his brief membership in the Independent Labour Party (ILP) stands out as a significant, albeit short-lived, chapter. The ILP, a left-wing socialist group, offered Orwell a platform that resonated with his anti-authoritarian and pro-working-class sentiments during the 1930s. This period marked a critical phase in his political evolution, as he sought to reconcile his ideals with practical political engagement.

To understand Orwell’s attraction to the ILP, consider the historical context. The 1930s were a time of economic hardship, rising fascism, and ideological polarization. The ILP, founded in 1893, had long advocated for democratic socialism, workers’ rights, and international solidarity. Unlike the mainstream Labour Party, the ILP maintained a staunchly pacifist stance and emphasized grassroots activism. Orwell, disillusioned by the failures of capitalism and the rise of totalitarian regimes, found in the ILP a group that mirrored his commitment to social justice and his skepticism of centralized power. His experiences in the Spanish Civil War, where he fought alongside ILP-affiliated militants, further solidified his temporary alignment with the party.

However, Orwell’s membership in the ILP was short-lived, lasting only from 1938 to 1940. His disillusionment stemmed from what he perceived as the party’s ideological rigidity and ineffectiveness in confronting fascism. Orwell believed that the ILP’s pacifism, while principled, was impractical in the face of Hitler’s aggression. This critique foreshadowed his later arguments in works like *Homage to Catalonia* and *Nineteen Eighty-Four*, where he warned against the dangers of dogmatic thinking and the betrayal of revolutionary ideals. His departure from the ILP marked a turning point, as he increasingly focused on individual freedoms and the critique of all forms of authoritarianism, whether from the right or the left.

For those interested in Orwell’s political journey, studying his ILP phase offers valuable insights. It highlights the tension between ideological purity and pragmatic action, a dilemma many activists face. To engage with this aspect of Orwell’s life, start by reading his essays from this period, such as *“Why I Joined the ILP”* (1938). Pair this with historical accounts of the ILP’s role in the Spanish Civil War to grasp the broader context. Practical tip: Use primary sources to avoid oversimplifying Orwell’s views, as his relationship with the ILP was nuanced, reflecting both his hopes and frustrations with organized politics.

In conclusion, Orwell’s brief stint in the Independent Labour Party was more than a footnote in his biography; it was a critical experiment in aligning his ideals with political action. While he ultimately moved away from the ILP, this phase underscores his enduring commitment to social justice and his relentless critique of power structures. By examining this period, readers can better appreciate Orwell’s evolution from a partisan activist to a universal critic of oppression, offering lessons for anyone navigating the complexities of political engagement today.

Understanding Evangelicals' Political Influence: Beliefs, Impact, and Modern Role

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Anti-Stalinism: Orwell opposed totalitarianism, including Stalinist communism

George Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair, was not formally affiliated with any political party, but his writings and actions reveal a deep commitment to democratic socialism and a fierce opposition to totalitarianism. His experiences during the Spanish Civil War, where he witnessed the brutal suppression of Trotskyist and anarchist factions by Stalinist forces, crystallized his anti-Stalinist stance. Orwell’s novel *Animal Farm* is a scathing allegory of the Russian Revolution and Stalin’s betrayal of its ideals, illustrating how totalitarian regimes corrupt revolutionary movements. This work underscores his belief that Stalinism was not merely a flawed implementation of communism but a perversion of its core principles.

Orwell’s anti-Stalinism was rooted in his broader rejection of totalitarianism, which he saw as the antithesis of individual freedom and democratic values. In *Nineteen Eighty-Four*, he depicted a dystopian society under the control of a totalitarian regime, drawing heavily from his observations of Stalinist practices. The novel’s Party, led by the omnipresent Big Brother, employs surveillance, propaganda, and historical revisionism—tactics Orwell associated with Stalin’s Soviet Union. By highlighting these mechanisms, Orwell warned of the dangers of unchecked state power and the erosion of truth in totalitarian systems.

To understand Orwell’s anti-Stalinism, consider his essay *“Second Thoughts on James Burnham”*, where he critiques Burnham’s pessimistic view of socialism while reaffirming his own commitment to democratic socialism. Orwell argued that socialism must be rooted in grassroots democracy and economic equality, contrasting it with the authoritarianism of Stalinism. He believed that Stalinist regimes, despite their claims of representing the proletariat, ultimately served the interests of a new ruling class. This analysis underscores his conviction that true socialism could never coexist with totalitarian methods.

Practically, Orwell’s anti-Stalinism offers a cautionary tale for modern political movements. His works encourage readers to scrutinize regimes that claim to act in the name of the people while suppressing dissent and consolidating power. For instance, Orwell’s emphasis on the importance of intellectual honesty and resistance to propaganda remains relevant in an era of misinformation. Activists and policymakers can draw from his example by advocating for transparency, protecting civil liberties, and fostering open debate—principles antithetical to totalitarianism.

In conclusion, Orwell’s anti-Stalinism was not merely a reaction to Stalin’s policies but a principled rejection of totalitarianism as a system. His writings serve as a timeless warning against the dangers of authoritarianism, regardless of its ideological label. By championing democratic socialism and individual freedom, Orwell provided a blueprint for resisting oppressive regimes and safeguarding the values of equality and justice. His legacy reminds us that the fight against totalitarianism is ongoing and requires vigilance, courage, and a commitment to truth.

Exploring Global Politics: How Many Countries Have Republican Parties?

You may want to see also

Anarchist Influences: His views were shaped by anarchist ideas, though he never formally joined

George Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair, was deeply influenced by anarchist ideas, though he never formally aligned himself with any anarchist organization. His experiences during the Spanish Civil War, particularly his time fighting alongside the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista), exposed him to anarchist principles in practice. The POUM, while Marxist, shared many anarchist ideals, such as decentralization and worker autonomy, which resonated with Orwell. This period was pivotal in shaping his skepticism of authoritarian structures, a theme that permeates his works like *Homage to Catalonia* and *1984*.

Anarchist thought emphasizes the rejection of hierarchical power and the belief in voluntary association. Orwell’s critique of totalitarianism in *Animal Farm* and *1984* reflects this anarchist ethos, as he exposes how centralized authority corrupts and oppresses. His portrayal of the pigs in *Animal Farm* seizing control and mimicking human tyranny mirrors anarchist warnings about the dangers of unchecked power. While Orwell’s political philosophy was complex, his distrust of state power and his advocacy for individual freedom align closely with anarchist principles.

To understand Orwell’s anarchist leanings, consider his practical advice in *Homage to Catalonia*: he praises the egalitarian spirit of anarchist militias, where officers and soldiers shared equal status. This firsthand observation contrasts sharply with the rigid hierarchies of traditional armies. For those exploring anarchist ideas, Orwell’s works serve as a cautionary tale about the fragility of freedom in the face of authoritarianism. His writing encourages readers to question power structures and advocate for decentralized, community-driven solutions.

While Orwell never identified as an anarchist, his views were undeniably shaped by anarchist ideals. His emphasis on personal liberty, opposition to tyranny, and critique of state control reflect core anarchist tenets. For modern readers, Orwell’s work offers a bridge between anarchist theory and practical resistance to oppression. By studying his writings, one can glean actionable insights into how anarchist principles can inform contemporary struggles for justice and equality. Orwell’s legacy reminds us that the fight against authoritarianism is timeless and universal.

Where to Buy Political Shirts: Top Stores for Statement Tees

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Orwell was not formally affiliated with any political party, but he was a democratic socialist and supported the Labour Party in the UK, particularly during the 1945 general election.

No, George Orwell never joined the Communist Party. He was highly critical of totalitarianism, including Stalinism, as evidenced in his works like *Animal Farm* and *Nineteen Eighty-Four*.

Yes, George Orwell briefly joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in the 1930s, a left-wing socialist party in the UK, but he later distanced himself from it due to ideological differences.

![By George Orwell QIAO ZHI AO WEI ER Politics and the English Language [Paperback]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41ipWGFhDkL._AC_UY218_.jpg)