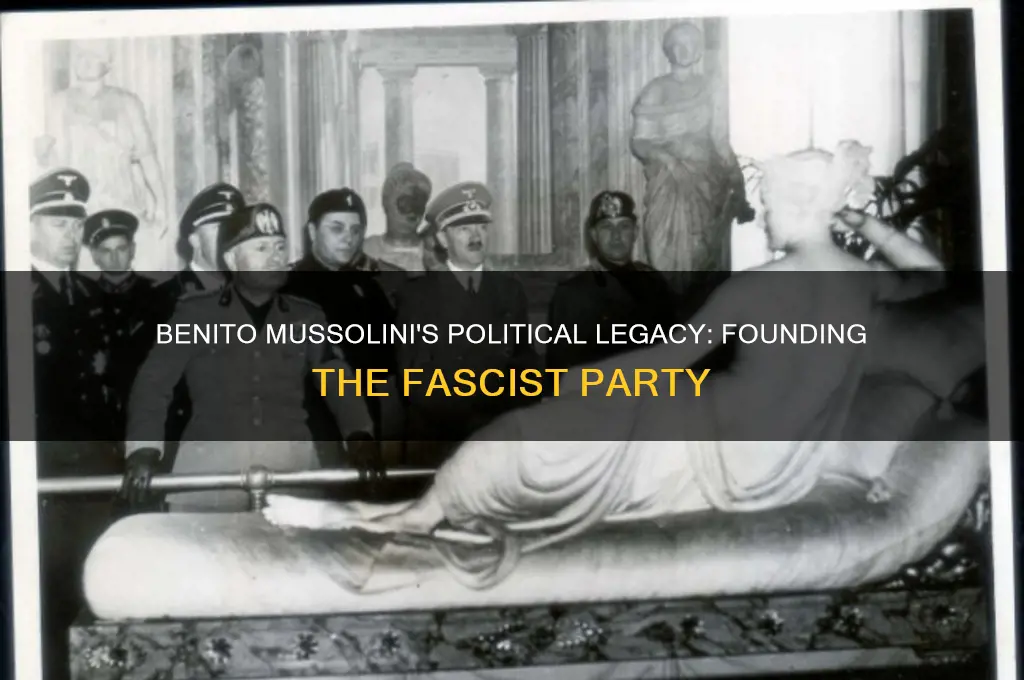

Benito Mussolini, a prominent figure in 20th-century history, founded the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) in Italy. Established in 1921, the party emerged from the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, a nationalist movement Mussolini had created in 1919. The PNF advocated for a totalitarian, authoritarian regime, emphasizing extreme nationalism, militarism, and the suppression of opposition. Under Mussolini's leadership, the party rose to power in 1922 following the March on Rome, marking the beginning of Fascist rule in Italy. The PNF played a central role in shaping Italy's political landscape until its dissolution in 1943, following Mussolini's ousting during World War II.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) |

| Founder | Benito Mussolini |

| Founded | November 9, 1921 |

| Dissolved | July 27, 1943 (officially banned in 1945) |

| Ideology | Fascism, Italian nationalism, Corporatism, Totalitarianism, Anti-communism, Anti-liberalism, Ultranationalism |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Symbol | Fasces (a bundle of rods with an axe) |

| Colors | Black |

| Newspaper | Il Popolo d'Italia (The People of Italy) |

| Youth wing | Opera Nazionale Balilla (later Gioventù Italiana del Littorio) |

| Notable members | Benito Mussolini, Achille Starace, Roberto Farinacci, Giuseppe Bottai |

| Key policies | Centralized authoritarian state, suppression of opposition, corporatist economic model, aggressive foreign policy, promotion of Italian cultural supremacy |

| Historical context | Rose to power in Italy after the March on Rome in 1922, ruled Italy as a dictatorship until 1943, closely allied with Nazi Germany during World War II |

| Legacy | Banned and dissolved after Italy's surrender in WWII, fascism remains a controversial and widely condemned ideology |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fascist Movement Origins: Mussolini's role in founding the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919

- National Fascist Party: Transformation into the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF) in 1921

- Ideological Foundations: Combining nationalism, totalitarianism, and anti-communism as core principles

- March on Rome: PNF's rise to power through the 1922 political demonstration

- Legacy and Dissolution: PNF's demise in 1943 after Mussolini's fall from power

Fascist Movement Origins: Mussolini's role in founding the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919

Benito Mussolini's role in founding the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Combat Fasci) in 1919 marked the inception of the Fascist movement in Italy. This organization, established in Milan, emerged from Mussolini's disillusionment with the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and his evolving political ideology. The Fasci Italiani di Combattimento was not merely a political party but a radical movement that blended nationalism, anti-communism, and authoritarianism, setting the stage for Fascism's rise in Europe.

The Catalyst for Change: Mussolini's Break from Socialism

Mussolini's expulsion from the PSI in 1914 for advocating Italy's entry into World War I was a pivotal moment. His wartime experiences and the subsequent social unrest in Italy fueled his shift from socialism to a more aggressive, nationalist stance. By 1919, he had coalesced a group of disaffected veterans, nationalists, and anti-communist activists. The Fasci Italiani di Combattimento was their vehicle to oppose the perceived weaknesses of liberal democracy and the growing threat of socialism, which Mussolini now viewed as a danger to national unity.

Ideological Foundations: The Fascist Manifesto

The movement's ideology was outlined in the Fascist Manifesto of 1919, which called for a strong, centralized state, corporatism, and the suppression of class conflict. Mussolini's vision was not fully formed at this stage, but the manifesto laid the groundwork for Fascism's core principles. It emphasized national revival, militarism, and the rejection of parliamentary politics, appealing to those who felt betrayed by Italy's post-war political and economic failures.

Strategic Mobilization: The Use of Violence and Propaganda

Mussolini's Fasci Italiani di Combattimento employed paramilitary tactics and propaganda to gain influence. The "Blackshirts," as they became known, used violence to intimidate opponents, particularly socialists and communists. This strategy, combined with Mussolini's charismatic leadership and his newspaper *Il Popolo d'Italia*, helped the movement gain traction among disillusioned Italians. By framing Fascism as a revolutionary force against both capitalism and communism, Mussolini positioned himself as a savior of the nation.

Legacy and Transformation: From Fasci to Fascism

The Fasci Italiani di Combattimento evolved into the National Fascist Party (PNF) in 1921, solidifying Mussolini's leadership and the movement's trajectory. The March on Rome in 1922 marked the Fascists' seizure of power, culminating in Mussolini's appointment as Prime Minister. While the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento was short-lived, it was the crucible in which Italian Fascism was forged, shaping the political landscape of Italy and influencing authoritarian movements worldwide.

Practical Takeaway: Understanding Fascist Origins

Studying the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento offers insight into how extremist movements exploit societal crises. Mussolini's ability to pivot from socialism to nationalism, coupled with his use of violence and propaganda, demonstrates the adaptability and danger of ideological extremism. For historians and political analysts, this period underscores the importance of addressing economic and political grievances before they fuel authoritarian responses.

Exploring the Pirate Party: A Global Political Movement for Digital Freedom

You may want to see also

National Fascist Party: Transformation into the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF) in 1921

Benito Mussolini founded the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919, a movement that would evolve into the National Fascist Party (PNF) by 1921. This transformation was not merely a rebranding but a strategic shift to consolidate power and appeal to a broader base. The PNF emerged as a disciplined, hierarchical organization, distinct from its earlier, more chaotic incarnation. Mussolini’s vision was to create a party that could dominate Italian politics through a combination of nationalism, authoritarianism, and populist rhetoric.

The restructuring into the PNF in 1921 was marked by several key changes. First, the party adopted a centralized leadership model, with Mussolini at its apex. This eliminated internal rivalries and ensured unity of purpose. Second, the PNF formalized its paramilitary wing, the Blackshirts, which became a tool for intimidation and control. These squads were deployed to suppress opposition, particularly socialists and communists, and to enforce Fascist ideology through violence. Third, the party expanded its membership by appealing to diverse groups, including veterans, industrialists, and rural landowners, who were drawn to its promises of order and national revival.

Analytically, the transformation into the PNF reflects Mussolini’s understanding of the political landscape. By 1921, Italy was in turmoil, with economic instability, social unrest, and a weak liberal government. The PNF positioned itself as the solution, offering a strong, centralized authority that could restore Italy’s greatness. Mussolini’s ability to adapt the Fascist movement to these conditions was crucial. He recognized that a loosely organized revolutionary group would not suffice; a structured, disciplined party was needed to seize and maintain power.

Instructively, the PNF’s success offers lessons in political strategy. To replicate such a transformation, one must first identify the weaknesses of existing systems and exploit them. Second, building a loyal, hierarchical organization is essential for control. Third, combining ideological appeal with practical solutions—such as the PNF’s focus on law and order—can attract a wide following. However, caution is necessary: the PNF’s methods, particularly its reliance on violence and suppression of dissent, are morally reprehensible and unsustainable in democratic societies.

Comparatively, the PNF’s evolution contrasts with other authoritarian movements of the time. While the Nazi Party in Germany also emphasized nationalism and hierarchy, it emerged from a defeated nation and capitalized on economic collapse. The PNF, by contrast, arose in a post-war Italy that, though unstable, was not as devastated. Mussolini’s ability to co-opt existing institutions, such as the monarchy and the Catholic Church, further distinguishes the PNF’s strategy. This pragmatic approach allowed Fascism to gain legitimacy and consolidate power incrementally.

In conclusion, the transformation of Mussolini’s movement into the PNF in 1921 was a pivotal moment in Fascist history. It exemplified how a political party could adapt to seize power in a turbulent environment. While the PNF’s methods are not to be emulated, its strategic insights into organization, appeal, and power consolidation remain a subject of study for understanding authoritarian regimes. The PNF’s legacy serves as a reminder of the dangers of unchecked nationalism and the importance of safeguarding democratic institutions.

Climbing the Political Ladder: Strategies for Rising in a Party

You may want to see also

Ideological Foundations: Combining nationalism, totalitarianism, and anti-communism as core principles

Benito Mussolini founded the National Fascist Party in Italy, a movement that distilled its ideological vigor from a potent blend of nationalism, totalitarianism, and anti-communism. These principles were not merely decorative elements but the very scaffolding of Fascist doctrine, each reinforcing the others to create a rigid, authoritarian structure. Nationalism provided the emotional core, totalitarianism the organizational framework, and anti-communism the adversarial purpose. Together, they formed a trinity of ideas that justified Mussolini’s rise to power and his regime’s brutal policies.

Consider nationalism as the lifeblood of Fascism. Mussolini harnessed Italy’s post-World War I disillusionment—the so-called *vittoria mutilata* (mutilated victory)—to stoke a fervent pride in Italian identity. He promised to restore Italy’s greatness, not through diplomacy, but through aggressive expansionism and cultural homogenization. This nationalism was exclusionary, glorifying the state above the individual and demanding absolute loyalty. Practical examples include the regime’s emphasis on Roman symbolism, the cult of personality around Mussolini, and the suppression of regional languages and cultures. For those seeking to understand Fascist ideology, note how nationalism served as both a rallying cry and a tool for erasing dissent.

Totalitarianism was the machinery that turned Fascist ideology into reality. Unlike mere authoritarianism, totalitarianism seeks to control every aspect of public and private life. Mussolini’s regime infiltrated schools, workplaces, and even leisure activities to ensure conformity. The Doctrine of Fascism, co-written by Mussolini, explicitly stated, “The Fascist conception of the State is all-embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value.” To implement this, the Fascists established organizations like the Opera Nazionale Balilla, a youth group designed to indoctrinate children from as young as 8 years old. For modern readers, this serves as a cautionary tale: totalitarianism thrives by dismantling individual autonomy, often under the guise of unity or security.

Anti-communism was the ideological adversary that gave Fascism its sense of purpose. Mussolini, once a socialist himself, pivoted sharply to the right, positioning Fascism as the bulwark against Bolshevism. This was not merely a theoretical opposition but a practical strategy to win support from industrialists, landowners, and the Catholic Church. The March on Rome in 1922, which cemented Mussolini’s power, was framed as a preemptive strike against a communist uprising. For those analyzing political movements, observe how anti-communism allowed Fascism to present itself as a protector of traditional values, even as it dismantled democratic institutions.

In combining these principles, Mussolini created a self-sustaining ideology. Nationalism provided the emotional fuel, totalitarianism the control mechanisms, and anti-communism the external threat. Together, they formed a closed system that brooked no opposition and demanded total adherence. For historians and political theorists, the Fascist Party’s ideological foundations offer a case study in how abstract ideas can be weaponized to reshape societies. For the general reader, it’s a reminder that the fusion of nationalism, totalitarianism, and anti-communism is not merely a historical curiosity but a blueprint that has reappeared in various forms across the globe.

Is 'Would You Mind' Truly Polite? Exploring Etiquette and Respect

You may want to see also

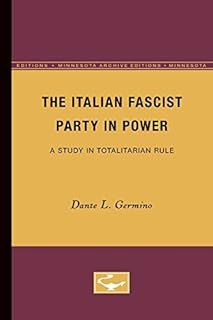

Explore related products

$11.99

$8.97 $9.99

March on Rome: PNF's rise to power through the 1922 political demonstration

The March on Rome in 1922 was a pivotal event that catapulted Benito Mussolini’s National Fascist Party (PNF) to power in Italy. It was not a spontaneous uprising but a carefully orchestrated political demonstration designed to exploit the nation’s instability. Mussolini, who had founded the PNF in 1921, leveraged widespread discontent with the liberal government, economic turmoil, and fear of socialist uprisings to position himself as a strong alternative. The march itself was more symbolic than militant; only a few thousand blackshirt supporters gathered outside Rome, while Mussolini remained in Milan, ready to negotiate rather than fight. This strategic blend of intimidation and political maneuvering proved effective, as King Victor Emmanuel III, fearing civil war, appointed Mussolini as Prime Minister, marking the beginning of Fascist rule in Italy.

To understand the march’s success, consider its tactical brilliance. Mussolini’s PNF capitalized on Italy’s post-World War I fragility, where the government’s failure to address economic crises and social unrest created a vacuum of authority. The Fascists framed themselves as the only force capable of restoring order, using paramilitary squads to suppress strikes and leftist opposition. The march was the culmination of this strategy, a dramatic display of strength that forced the monarchy to choose between chaos and Fascist control. Unlike a traditional coup, it relied on psychological pressure rather than outright violence, showcasing Mussolini’s ability to manipulate both public fear and elite indecision.

A comparative analysis highlights the march’s uniqueness in the context of 20th-century power grabs. While other regimes rose through revolution or electoral means, the PNF’s ascent was a hybrid of political theater and coercion. It differed from Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution, which relied on mass mobilization and armed insurrection, or Hitler’s later rise, which combined electoral success with paramilitary intimidation. The March on Rome was a masterclass in leveraging symbolism—the image of blackshirts marching on the capital resonated far beyond their actual numbers, creating an illusion of unstoppable momentum. This approach underscored the Fascists’ understanding of propaganda and its role in shaping political outcomes.

For those studying political movements, the March on Rome offers critical lessons in the dynamics of power. First, it demonstrates how a minority group can seize control by exploiting societal divisions and institutional weaknesses. Second, it highlights the importance of timing; Mussolini acted during a moment of peak instability, when the government was too weak to resist. Finally, it serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of appeasing authoritarian movements. The monarchy’s decision to appoint Mussolini, hoping to contain him, instead legitimized Fascist rule and paved the way for dictatorship. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for recognizing and countering similar tactics in modern contexts.

Practically speaking, the March on Rome provides a framework for analyzing contemporary political demonstrations. Organizers of protests or movements can learn from the Fascists’ use of symbolism and timing, though ethical considerations must always guide such strategies. For policymakers, the event underscores the need to address underlying social and economic grievances before they escalate into crises. By studying the PNF’s rise, we gain insights into how fragile democracies can be manipulated and the importance of robust institutions in safeguarding against authoritarianism. The march remains a stark reminder of the consequences when fear and division are allowed to dictate political outcomes.

Pakistan's Political Turmoil: Unraveling the Roots of Instability and Conflict

You may want to see also

Legacy and Dissolution: PNF's demise in 1943 after Mussolini's fall from power

Benito Mussolini founded the National Fascist Party (PNF), which became the dominant political force in Italy from 1922 to 1943. The PNF's rise was marked by its authoritarian ideology, centralized control, and Mussolini's cult of personality. However, its demise in 1943 was a direct consequence of Mussolini's fall from power, precipitated by Italy's disastrous involvement in World War II and growing internal dissent.

The Catalysts for Collapse

By 1943, Italy's military failures on multiple fronts—from North Africa to the Eastern Front—had eroded public confidence in the Fascist regime. The Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943 exposed the regime's vulnerability, while economic hardship and food shortages fueled widespread discontent. The Grand Council of Fascism, once a rubber-stamp body, turned against Mussolini, voting to remove him from power on July 25, 1943. This internal betrayal, coupled with King Victor Emmanuel III's decision to arrest Mussolini, marked the beginning of the PNF's dissolution.

The Mechanisms of Disintegration

Following Mussolini's ousting, the PNF's organizational structure crumbled rapidly. The party's reliance on Mussolini's leadership left it without a clear successor or coherent ideology. The new government, led by Marshal Pietro Badoglio, disbanded the PNF and outlawed Fascism, dismantling its institutions and propaganda apparatus. Regional party branches, once tightly controlled by Rome, dissolved into chaos as members either fled, defected, or were arrested. The party's demise was not just political but also symbolic, as the Fascist regime's collapse signaled the end of an era.

The Aftermath and Legacy

While the PNF ceased to exist in 1943, its legacy persisted in the form of the Italian Social Republic, a puppet state established by Mussolini with German support later that year. However, this was a shadow of the former regime, lacking legitimacy and control. The PNF's dissolution paved the way for Italy's post-war transition to democracy, but it also left a complex legacy of authoritarianism and nationalism that continues to influence Italian politics. The party's rise and fall serve as a cautionary tale about the dangers of centralized power and the fragility of ideological regimes.

Practical Takeaways for Understanding Political Collapse

To analyze the dissolution of parties like the PNF, focus on three key factors: leadership dependency, external pressures, and internal fractures. Parties built around a single figure are inherently vulnerable to collapse when that leader falls. External crises, such as military defeats or economic failures, can accelerate this process. Finally, internal dissent—whether from elites or the public—often serves as the final blow. By examining these dynamics, historians and political analysts can better understand the mechanisms of political disintegration and their long-term consequences.

Navigating Political Uncertainty: Best Business Strategies for Stability and Growth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Benito Mussolini founded the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) in Italy.

Mussolini established the National Fascist Party in 1921, after reorganizing his earlier movement, the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, which was founded in 1919.

The core principles of Mussolini's Fascist Party included nationalism, totalitarianism, corporatism, and the rejection of liberalism, socialism, and democracy.

Mussolini's Fascist Party rose to power through a combination of political manipulation, violence, and the March on Rome in 1922, which led to his appointment as Prime Minister by King Victor Emmanuel III.

The Fascist Party became the sole legal political party in Italy after Mussolini established a dictatorship in 1925, controlling all aspects of government and society until its dissolution in 1943.