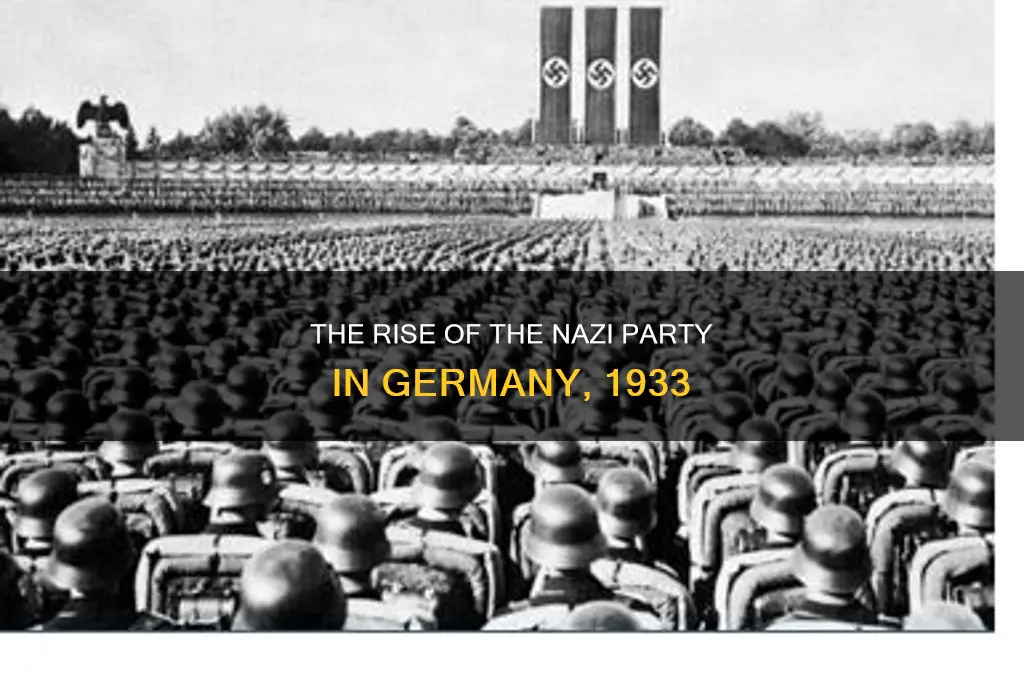

In 1933, the National Socialist German Workers' Party, commonly known as the Nazi Party, rose to power in Germany, marking a pivotal and devastating turning point in world history. Led by Adolf Hitler, the party capitalized on widespread economic hardship, political instability, and nationalistic sentiment following World War I to gain support. After being appointed Chancellor in January 1933, Hitler swiftly consolidated power through the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act, effectively dismantling democratic institutions and establishing a totalitarian regime. This takeover ushered in an era of extreme nationalism, persecution of minorities, and ultimately, the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) |

| Commonly Known As | Nazi Party |

| Leader in 1933 | Adolf Hitler |

| Year of Taking Control | 1933 |

| Method of Taking Control | Appointed as Chancellor through political maneuvering and the Enabling Act |

| Ideology | Nazism (Fascism, Ultranationalism, Antisemitism, Racial Supremacy) |

| Symbol | Swastika |

| Official Color | Red, White, and Black |

| Key Policies | Totalitarianism, Persecution of Jews, Expansionism, Militarization |

| Duration of Rule | 1933–1945 |

| Outcome of Rule | World War II, Holocaust, Fall of Nazi Germany in 1945 |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Hitler's Rise to Power: How Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933

- Enabling Act: Passed in March 1933, it granted Hitler dictatorial powers

- Nazi Party Structure: Organization and key figures within the National Socialist German Workers' Party

- Suppression of Opposition: Elimination of political rivals and consolidation of Nazi control

- Reichstag Fire: Event used by Nazis to justify emergency powers and suppress dissent

Hitler's Rise to Power: How Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933

Adolf Hitler’s ascent to power in January 1933 was not a sudden event but the culmination of years of strategic manipulation, political maneuvering, and exploitation of Germany’s vulnerabilities. The Nazi Party, formally known as the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), seized control of Germany in 1933, marking the beginning of one of the darkest chapters in human history. Hitler’s rise was fueled by a toxic mix of economic despair, nationalist fervor, and a deeply flawed political system that allowed a demagogue to exploit its weaknesses.

The Weimar Republic, Germany’s democratic government established after World War I, was plagued by instability from its inception. Hyperinflation in the early 1920s, the humiliating terms of the Treaty of Versailles, and the global economic crisis of the Great Depression left millions of Germans disillusioned and desperate for change. Hitler capitalized on this discontent, offering simple yet radical solutions: blame the Jews, communists, and other minorities for Germany’s woes, restore national pride, and rebuild the economy through authoritarian control. His charismatic oratory and the Nazi Party’s aggressive propaganda machine resonated with a population yearning for stability and revenge.

Hitler’s path to the chancellorship was paved by a series of calculated moves. In the 1932 elections, the Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag, though they failed to secure a majority. President Paul von Hindenburg, a staunch conservative, initially resisted appointing Hitler as chancellor, viewing him as a radical and untrustworthy. However, behind-the-scenes negotiations, particularly by conservative politicians like Franz von Papen, convinced Hindenburg that Hitler could be controlled. On January 30, 1933, Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor, believing he could use the Nazis to weaken the left and consolidate conservative power. This miscalculation would prove catastrophic.

Once in office, Hitler moved swiftly to consolidate power. The Reichstag fire on February 27, 1933, provided the pretext for the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended civil liberties and allowed mass arrests of political opponents. The Enabling Act, passed in March 1933, granted Hitler dictatorial powers, effectively dismantling the Weimar Republic. Within months, the Nazi Party had eliminated all opposition, established a one-party state, and begun implementing its racist and authoritarian agenda. Hitler’s rise was a masterclass in exploiting democratic institutions to destroy democracy itself.

The lessons of Hitler’s ascent remain starkly relevant. His success hinged on the manipulation of public fear, the erosion of democratic norms, and the complicity of elites who underestimated his ambitions. Understanding this history is not merely an academic exercise but a cautionary tale for safeguarding democratic systems against authoritarian threats. It underscores the importance of vigilance, the defense of institutions, and the rejection of divisive ideologies that prey on societal vulnerabilities.

Jefferson's Views on Political Parties: Unity vs. Division

You may want to see also

Enabling Act: Passed in March 1933, it granted Hitler dictatorial powers

The Enabling Act, passed on March 23, 1933, marked a turning point in German history, as it legally transferred unprecedented power to Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party. This act, formally titled the "Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich," effectively dismantled the Weimar Republic's democratic framework and established the foundation for Hitler's dictatorship. By granting the Chancellor's office the authority to enact laws without parliamentary consent, it bypassed the Reichstag, Germany's legislative body, and concentrated all decision-making power in Hitler's hands.

To understand the Enabling Act's significance, consider the context in which it was passed. Following the Reichstag fire on February 27, 1933, Hitler exploited the crisis to push for emergency powers. The fire, which the Nazis blamed on communists, created an atmosphere of fear and urgency. Using the Reichstag Fire Decree, Hitler suspended civil liberties and intensified political repression. The Enabling Act was the next step in this power grab, presented as a necessary measure to restore order and protect the nation from perceived threats.

The passage of the Enabling Act was not without controversy. While the Nazis held a significant number of seats in the Reichstag, they still needed a two-thirds majority to pass the act. To achieve this, they employed a combination of intimidation and political maneuvering. The Center Party, for instance, was coerced into supporting the act after receiving assurances that the Church's rights would be protected. Meanwhile, the Communists, who would have opposed the act, were largely absent due to arrests and intimidation. The vote itself took place in an atmosphere of fear, with Nazi stormtroopers surrounding the building to ensure compliance.

From a practical standpoint, the Enabling Act had immediate and far-reaching consequences. It allowed Hitler to consolidate power rapidly, eliminating any remaining checks on his authority. Within months, all other political parties were banned, and the Nazi Party became the sole legal party in Germany. The act also enabled Hitler to pursue his aggressive domestic and foreign policies without legislative hindrance, setting the stage for the totalitarian regime that would define Nazi Germany. This period underscores the dangers of eroding democratic institutions and the importance of safeguarding constitutional checks and balances.

In retrospect, the Enabling Act serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of democracy and the ease with which authoritarianism can take root. It highlights how a combination of crisis, fear, and political manipulation can lead to the surrender of fundamental freedoms. For modern societies, the lesson is clear: vigilance in protecting democratic norms and institutions is essential, as the erosion of these principles can have irreversible consequences. The Enabling Act remains a stark reminder of how quickly a nation can transition from democracy to dictatorship when the rule of law is compromised.

Unveiling the Author Behind World Political Geography: A Historical Insight

You may want to see also

Nazi Party Structure: Organization and key figures within the National Socialist German Workers' Party

The Nazi Party, officially known as the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), rose to power in Germany in 1933, marking the beginning of a totalitarian regime. Central to its success was a meticulously structured organization designed to consolidate control and propagate its ideology. At its core, the party was divided into hierarchical levels, each with specific roles and responsibilities, ensuring efficiency and loyalty. Understanding this structure reveals how the Nazis maintained power and executed their agenda.

The party’s leadership was dominated by Adolf Hitler, who held the title of Führer (leader), wielding absolute authority. Beneath him was the Reichsleitung (National Leadership), comprising key figures like Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels. Göring, as head of the Luftwaffe and later Reichsmarschall, controlled the air force and economic resources. Himmler, as Reichsführer-SS, commanded the SS (Schutzstaffel), the party’s elite paramilitary force, and oversaw the Gestapo and concentration camps. Goebbels, as Minister of Propaganda, masterminded the regime’s ideological messaging, ensuring public compliance through manipulation and censorship. These men formed the inner circle, driving the party’s policies and enforcing Hitler’s vision.

Below the national leadership were regional and local organizations, such as the Gauleiters (regional leaders) and Kreisleiters (district leaders), who acted as intermediaries between the central authority and local populations. The party also established specialized branches like the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend) for indoctrinating young people and the German Labor Front (DAF) to control trade unions and labor policies. Each branch operated with military-like discipline, ensuring every aspect of German society was aligned with Nazi ideology. This decentralized yet tightly controlled structure allowed the party to penetrate all levels of society, from urban centers to rural villages.

A critical aspect of the Nazi Party’s organization was its reliance on paramilitary groups. The SA (Sturmabteilung), or Stormtroopers, initially served as the party’s street fighters, intimidating opponents and disrupting political rallies. Later, the SS emerged as a more elite force, evolving into a powerful instrument of terror and genocide. The SS’s intelligence arm, the SD (Sicherheitsdienst), monitored dissent and coordinated surveillance, further tightening the regime’s grip on power. These groups not only enforced loyalty but also symbolized the party’s strength and ruthlessness.

In practice, the Nazi Party’s structure was a masterclass in totalitarian organization, blending hierarchy, specialization, and intimidation. By compartmentalizing roles and fostering competition among leaders, Hitler ensured no single figure could challenge his authority. This system enabled the rapid implementation of policies, from economic reforms to the persecution of Jews and other minorities. For historians and analysts, studying this structure offers insights into how authoritarian regimes operate and the dangers of centralized power. Understanding the Nazi Party’s organization is not just a lesson in history but a cautionary tale for safeguarding democratic institutions today.

Exploring Sweden's Political Spectrum: How Socialist Are Its Parties?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Suppression of Opposition: Elimination of political rivals and consolidation of Nazi control

The Nazi Party’s rise to power in 1933 was swiftly followed by a systematic campaign to eliminate political opposition and consolidate control. This process was not merely about silencing dissent but about dismantling the very structures that could challenge their authority. The first step involved targeting political rivals through legal and extralegal means, ensuring no organized opposition could survive. The Enabling Act of March 1933 granted Hitler dictatorial powers, effectively sidelining the Reichstag and allowing the Nazis to outlaw all other political parties by July 1933. This legal framework was the foundation for their suppression strategy.

The elimination of political rivals was both brutal and calculated. The Nazis employed the Sturmabteilung (SA) and later the Schutzstaffel (SS) to intimidate, arrest, and assassinate key figures from opposing parties. The Social Democrats, Communists, and centrist parties were particularly targeted. For instance, the Reichstag Fire in February 1933, blamed on the Communists, was used as a pretext to arrest thousands of Communist Party members, decimating their leadership. Similarly, the Night of the Long Knives in June 1934 saw the purge of SA leaders and political adversaries within the Nazi ranks, ensuring internal loyalty and external dominance.

Consolidation of control extended beyond political parties to encompass labor unions, media, and cultural institutions. The Nazis dissolved independent labor unions, replacing them with the German Labour Front, which served as a tool for propaganda rather than worker representation. Media outlets were either taken over or shut down, with the Ministry of Propaganda under Joseph Goebbels ensuring all publications aligned with Nazi ideology. This cultural homogenization was critical in stifling dissent and creating an illusion of unanimous support for the regime.

A key takeaway from this suppression campaign is the importance of controlling institutions to maintain power. By dismantling opposition parties, neutralizing potential challengers, and monopolizing information, the Nazis created an environment where resistance was nearly impossible. This strategy was not just about physical control but also psychological—fear and propaganda worked in tandem to ensure compliance. For modern societies, this serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of eroding democratic institutions and the need to protect pluralism and free expression.

Practical steps to counter such suppression include strengthening legal frameworks that protect opposition parties, ensuring independent media, and fostering civic education that promotes critical thinking. Historical examples like the Nazi regime highlight the fragility of democracy and the necessity of vigilance against authoritarian tendencies. By understanding these mechanisms, societies can better safeguard against the erosion of freedoms and the rise of oppressive regimes.

MJ's Political Stance: Uncovering His Views and Activism

You may want to see also

Reichstag Fire: Event used by Nazis to justify emergency powers and suppress dissent

The Reichstag Fire of February 27, 1933, stands as a pivotal moment in the Nazi Party’s rise to absolute power in Germany. Within hours of the blaze engulfing the parliamentary building, Adolf Hitler and his regime exploited the event to justify sweeping emergency measures. The fire, allegedly set by Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe, provided the Nazis with a pretext to portray themselves as defenders of the nation against a supposed communist uprising. This narrative, amplified through state-controlled media, fueled public fear and rallied support for drastic actions. The Reichstag Fire Decree, signed by President Paul von Hindenburg the next day, suspended civil liberties, including freedom of speech, assembly, and press, effectively dismantling democratic safeguards.

Analyzing the aftermath reveals a calculated strategy to consolidate power. The Nazis used the decree to arrest thousands of political opponents, primarily communists and socialists, but also targeting journalists, intellectuals, and anyone deemed a threat. The suppression of dissent was systematic, with the Sturmabteilung (SA) and Schutzstaffel (SS) enforcing the regime’s will through intimidation and violence. By framing the fire as a terrorist act, Hitler’s government not only neutralized opposition but also legitimized its authoritarian rule in the eyes of the public. This event marked the beginning of the end for the Weimar Republic and the establishment of Nazi dictatorship.

A comparative perspective highlights the Reichstag Fire’s role as a blueprint for authoritarian regimes. Similar tactics—manufacturing crises, scapegoating minorities or political opponents, and exploiting fear—have been employed by leaders seeking to justify power grabs. For instance, the 1939 Gleiwitz incident, staged by Nazi Germany to provoke war with Poland, mirrors the Reichstag Fire’s manipulation of public perception. Understanding this historical event underscores the dangers of unchecked emergency powers and the erosion of democratic institutions under the guise of national security.

Practically, the Reichstag Fire serves as a cautionary tale for modern societies. To safeguard democracy, citizens must remain vigilant against the misuse of crisis narratives. Transparency in governance, independent media, and robust legal frameworks are essential to prevent the concentration of power. For educators and policymakers, teaching this event as a case study in political manipulation can foster critical thinking about the fragility of democratic norms. By learning from history, we can better recognize and resist efforts to undermine freedom in the name of security.

In conclusion, the Reichstag Fire was not merely a historical incident but a strategic tool wielded by the Nazis to justify authoritarianism. Its legacy reminds us of the ease with which fear can be weaponized to dismantle democracy. By examining this event critically, we gain insights into the mechanisms of power and the importance of protecting civil liberties, even—or especially—in times of crisis.

Exclusive Party Privileges: Actions Reserved for Political Party Members

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Nazi Party, officially known as the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), took control of Germany in 1933.

The Nazi Party gained power through a combination of political maneuvering, the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg, and the passage of the Enabling Act, which granted Hitler dictatorial powers.

Adolf Hitler was the leader of the Nazi Party and became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933.

The passage of the Enabling Act (Ermächtigungsgesetz) in March 1933 solidified the Nazi Party's control by giving Hitler the authority to enact laws without parliamentary consent.

No, the Nazi Party did not win an outright majority in the November 1932 elections, but they formed a coalition and leveraged political instability to gain power in 1933.

![The Rise of the Nazi Party - 4-DVD Box Set ( Nazis: Evolution of Evil ) [ NON-USA FORMAT, PAL, Reg.0 Import - United Kingdom ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71vrWMvQmVL._AC_UY218_.jpg)