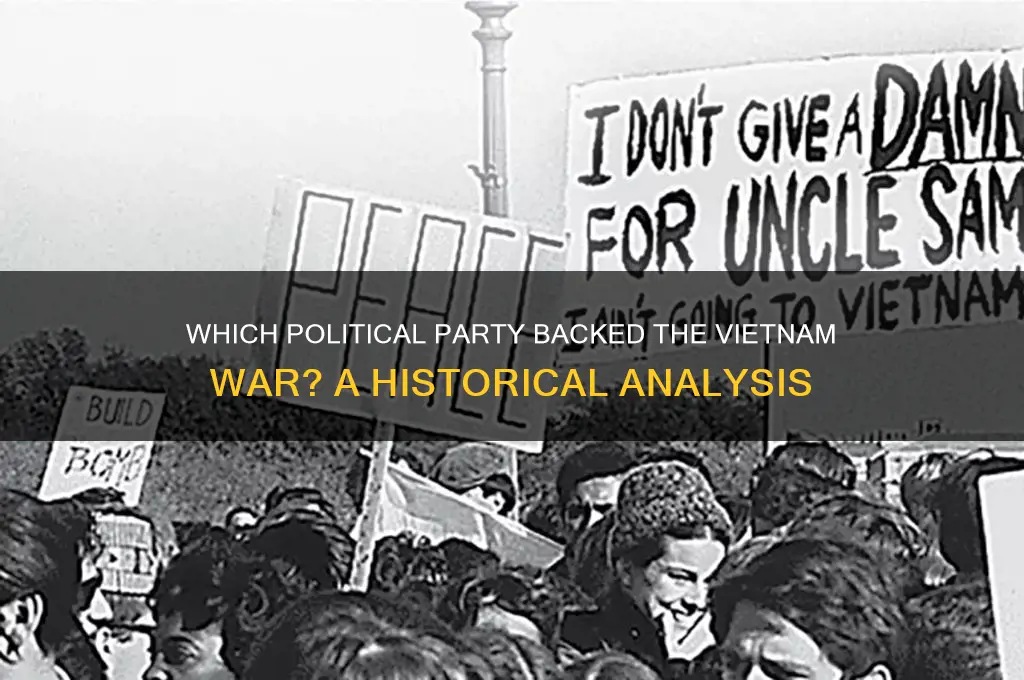

The Vietnam War, a prolonged and contentious conflict, garnered varying levels of support and opposition across the American political spectrum. Among the major political parties, the Republican Party generally emerged as a strong supporter of the war, particularly under the leadership of President Richard Nixon, who sought to achieve peace with honor through a policy of Vietnamization. Many Republicans viewed the war as a necessary effort to contain communism and uphold U.S. credibility on the global stage. In contrast, the Democratic Party became increasingly divided, with some members, like President Lyndon B. Johnson, initially backing the war but facing growing dissent from the party's liberal wing, which criticized the conflict's escalating costs, both in terms of human lives and financial resources. This internal Democratic opposition, coupled with widespread anti-war protests, ultimately contributed to a shift in public opinion and political priorities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Democratic Party (initially), Republican Party (later) |

| Initial Stance | The Democratic Party, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, initially supported the Vietnam War as part of the Cold War containment policy against communism. |

| Key Figures | Lyndon B. Johnson (Democratic), Robert McNamara (Secretary of Defense under Johnson) |

| Public Support | Initially high, but declined as the war prolonged and casualties mounted. |

| Shift in Support | The Republican Party, under President Richard Nixon, continued the war effort but sought to "Vietnamize" the conflict, gradually withdrawing U.S. troops. |

| Opposition | The anti-war movement gained momentum, primarily among Democrats, independents, and younger voters, leading to increased opposition within the Democratic Party. |

| Legacy | The war deeply divided both parties, with long-term impacts on U.S. foreign policy and political polarization. |

| Historical Context | The war was supported as a Cold War strategy to prevent the spread of communism, but its execution and outcomes remain highly controversial. |

| Current Perspective | Both parties now acknowledge the war's failures, though interpretations of its lessons vary, with Republicans often emphasizing strong national defense and Democrats focusing on the need for diplomatic solutions. |

Explore related products

$17.98 $38.95

What You'll Learn

- Democratic Party Divisions: Highlighting internal conflicts within the Democratic Party over Vietnam War support

- Republican Hawkish Stance: Discussing the Republican Party's consistent backing of the Vietnam War

- Southern Democrats' Support: Exploring why many Southern Democrats supported the war effort

- Liberal Opposition Growth: Tracing how liberal factions shifted to oppose the war

- Nixon’s Silent Majority: Analyzing Nixon’s appeal to Republicans and conservative Democrats for war support

Democratic Party Divisions: Highlighting internal conflicts within the Democratic Party over Vietnam War support

The Vietnam War exposed deep fractures within the Democratic Party, pitting liberal doves against establishment hawks in a battle for the party's soul. This internal conflict wasn't merely a difference of opinion; it was a clash of ideologies, generations, and visions for America's role in the world.

While President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Democrat, escalated U.S. involvement in Vietnam, a growing chorus of dissent emerged within his own party. Senators like Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern became vocal critics, tapping into a surging anti-war sentiment, particularly among young Democrats and the counterculture movement.

This divide wasn't simply about the war itself. It reflected a broader struggle between the party's traditional, Cold War-era foreign policy establishment and a new, more progressive wing advocating for social justice, civil rights, and a reevaluation of America's global military commitments. The war's escalating costs, both human and financial, further fueled this internal strife, as doves argued that resources were being diverted from domestic programs desperately needed at home.

The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago became a symbolic battleground for these divisions. Protests erupted outside the convention hall, mirroring the chaos within, where pro-war and anti-war factions clashed over the party platform and the nomination of Vice President Hubert Humphrey, seen by many as a symbol of the establishment's pro-war stance.

The Democratic Party's internal conflict over Vietnam had lasting consequences. It contributed to the party's defeat in the 1968 presidential election and paved the way for a realignment of American politics, with the anti-war movement becoming a defining force within the Democratic Party for decades to come. This period serves as a stark reminder of how foreign policy can become a powerful wedge issue, capable of tearing apart even the most established political parties.

Iowa's Political Hue: Red, Blue, or Swing State?

You may want to see also

Republican Hawkish Stance: Discussing the Republican Party's consistent backing of the Vietnam War

The Republican Party's unwavering support for the Vietnam War was rooted in its hawkish foreign policy doctrine, which emphasized military strength, anti-communist containment, and American global leadership. This stance was not merely a reaction to the Cold War but a consistent ideological position that shaped the party's approach to international conflicts. From the early 1950s, Republican leaders like Senator Barry Goldwater and President Dwight D. Eisenhower framed the war as a necessary battle against the spread of communism, a narrative that resonated deeply with the party's conservative base. This ideological commitment often overshadowed pragmatic concerns about the war's cost, both in lives and resources, cementing the GOP's reputation as the party of interventionist resolve.

To understand the Republican Party's hawkish stance, consider its strategic calculus during the Vietnam War. The party consistently argued that withdrawal from Vietnam would embolden the Soviet Union and China, leading to a domino effect of communist expansion in Southeast Asia. This fear-driven logic was exemplified in President Richard Nixon's "silent majority" speech, where he appealed to Americans who supported the war effort despite growing public dissent. The GOP's messaging framed opposition to the war as unpatriotic and weak, effectively silencing internal party dissent and maintaining a unified front. This approach not only sustained the war effort but also reinforced the party's identity as the guardian of American security interests abroad.

A comparative analysis of Republican and Democratic positions on the Vietnam War highlights the GOP's unique hawkishness. While Democrats like President Lyndon B. Johnson initially escalated the war, the party began to fracture by the late 1960s, with figures like Senator George McGovern advocating for withdrawal. In contrast, Republicans remained steadfast, viewing any retreat as a betrayal of American values and global responsibilities. This divergence was evident in congressional votes, where Republicans consistently opposed measures to limit funding or set withdrawal timelines. The party's ability to maintain this position despite mounting casualties and public opposition underscores its ideological rigidity and strategic discipline.

Practically, the Republican Party's hawkish stance had tangible consequences for both domestic and foreign policy. Domestically, it deepened political polarization, as anti-war sentiment became increasingly associated with the Democratic Party and the counterculture movement. Internationally, the GOP's unwavering support prolonged U.S. involvement in Vietnam, contributing to the war's eventual unpopularity and the erosion of American credibility abroad. For those studying political strategy, the Republican approach offers a case study in the risks and rewards of ideological consistency. While it solidified the party's identity, it also alienated moderate voters and undermined long-term public trust in government institutions.

In conclusion, the Republican Party's consistent backing of the Vietnam War was a defining feature of its hawkish foreign policy doctrine. By framing the conflict as a moral and strategic imperative, the GOP not only sustained the war effort but also shaped its own political identity for decades to come. This stance, while ideologically coherent, came at a significant cost, both in terms of human lives and America's global standing. For historians, policymakers, and political observers, the Republican Party's role in the Vietnam War serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of prioritizing ideology over pragmatism in foreign affairs.

Tragedy at the Podium: Fatalities in Political Rally History

You may want to see also

Southern Democrats' Support: Exploring why many Southern Democrats supported the war effort

The Vietnam War, a conflict that deeply divided the United States, saw surprising support from many Southern Democrats, a group often associated with conservative social policies and regional interests. This alignment might seem counterintuitive given the Democratic Party’s eventual shift toward anti-war sentiment. However, understanding this support requires examining the unique political, cultural, and historical context of the South during the 1960s and early 1970s.

Regional Loyalty and Anti-Communism: Southern Democrats, rooted in a region with strong military traditions and a deep-seated fear of communism, viewed the Vietnam War through a Cold War lens. The domino theory, which posited that the fall of one country to communism would lead to the collapse of others, resonated strongly in the South. Politicians like Senator John Stennis of Mississippi and Senator Richard Russell of Georgia championed the war as a necessary defense against the spread of communism, aligning with their constituents’ fears and values. This anti-communist sentiment was not merely ideological but also tied to regional pride, as many Southerners saw military service as a duty and a source of honor.

Economic and Political Pragmatism: The South’s economy was heavily dependent on defense contracts and military bases, which provided jobs and infrastructure. Supporting the war was, in many ways, a pragmatic decision to protect these economic interests. For instance, states like Texas and Alabama benefited significantly from defense spending, and their elected officials were keen to maintain this flow of federal funds. Additionally, Southern Democrats often used their support for the war to solidify their political standing, appealing to a conservative base that prioritized national security over social reform.

Cultural and Social Conservatism: The war effort also aligned with the cultural conservatism of many Southern Democrats. The 1960s were a time of significant social upheaval, with the civil rights movement, counterculture, and anti-war protests challenging traditional norms. Southern Democrats, often resistant to these changes, saw the war as a way to maintain order and assert traditional values. Supporting the war became a symbol of patriotism and stability, contrasting sharply with the perceived radicalism of anti-war activists.

The Role of Leadership: Key Southern Democratic leaders played a pivotal role in shaping public opinion. President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Texan and a Southern Democrat, escalated U.S. involvement in Vietnam, framing it as a moral and strategic imperative. His influence, combined with that of other Southern leaders, helped sustain support for the war even as public opinion began to shift. These leaders often framed the war in terms of national honor and duty, resonating deeply with their Southern constituents.

Takeaway: The support of many Southern Democrats for the Vietnam War was a complex interplay of regional loyalty, economic pragmatism, cultural conservatism, and strong leadership. While this stance eventually became a point of contention within the Democratic Party, it reflected the unique priorities and values of the South during this tumultuous period. Understanding this support offers insight into the broader political and social dynamics of the era, highlighting how regional identities can shape national policies.

How Political Parties Shape Society: Key Socialization Functions Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.59 $16.95

$16.99 $16.99

Liberal Opposition Growth: Tracing how liberal factions shifted to oppose the war

The Vietnam War initially enjoyed bipartisan support in the United States, with both major political parties endorsing the conflict during its early years. However, as the war dragged on, liberal factions within the Democratic Party began to shift their stance, ultimately becoming a driving force in the anti-war movement. This transformation was not immediate but rather a gradual process fueled by mounting casualties, draft resistance, and a growing skepticism of U.S. foreign policy.

Catalysts for Change: Key Events and Figures

The Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, which led to a significant escalation of U.S. involvement, initially united Democrats and Republicans behind the war effort. However, by 1967, the Tet Offensive exposed the war’s stalemate, shattering public confidence. Liberal senators like George McGovern and Eugene McCarthy emerged as vocal critics, leveraging their platforms to challenge the Johnson administration’s handling of the war. McCarthy’s 1968 presidential campaign, centered on an anti-war platform, signaled a fracture within the Democratic Party, as liberal voters began to prioritize peace over party loyalty.

Grassroots Mobilization: The Role of Activist Movements

Liberal opposition to the war was not confined to Capitol Hill. Grassroots movements, such as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the anti-war protests led by figures like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., amplified dissent. These movements framed the war as morally indefensible, linking it to broader issues of racial and economic injustice. The draft, which disproportionately affected low-income and minority communities, further galvanized liberal opposition, as activists argued that the war was both unjust and inequitable.

Strategic Shifts: From Support to Resistance

The shift in liberal sentiment was also strategic. As the war’s costs—both human and financial—mounted, liberal policymakers began to question its feasibility. The 1972 Democratic Party platform reflected this change, explicitly calling for an end to U.S. involvement in Vietnam. This marked a stark departure from the party’s earlier stance, illustrating how liberal factions had successfully reshaped the party’s foreign policy priorities.

Legacy and Lessons: The Impact of Liberal Opposition

The growth of liberal opposition to the Vietnam War had lasting implications for U.S. politics. It demonstrated the power of grassroots activism in influencing policy and highlighted the importance of moral and ethical considerations in foreign interventions. Today, this legacy informs liberal skepticism of military engagements, serving as a cautionary tale about the dangers of prolonged and unjust conflicts. For modern activists and policymakers, the Vietnam era offers a blueprint for challenging established narratives and advocating for peace.

Understanding the Liberal Party: Core Principles and Political Influence

You may want to see also

Nixon’s Silent Majority: Analyzing Nixon’s appeal to Republicans and conservative Democrats for war support

Richard Nixon's 1969 "Silent Majority" speech was a masterclass in political rhetoric, strategically targeting Republicans and conservative Democrats to solidify support for the Vietnam War. By invoking the image of a quiet yet powerful majority, Nixon tapped into a deep-seated American desire for stability and patriotism, framing opposition to the war as the noisy dissent of a radical fringe. This appeal was particularly effective among conservatives who viewed anti-war protests as unpatriotic and disruptive to traditional values. Nixon's message resonated with those who believed in a strong national defense and were wary of the counterculture movement, positioning himself as the defender of a muted but resolute majority.

To understand Nixon's strategy, consider the political landscape of the late 1960s. The Democratic Party was fractured, with liberal doves opposing the war and conservative hawks supporting it. Nixon, a Republican, sought to peel away these conservative Democrats by emphasizing shared values like law and order, national pride, and resistance to communism. His speech was a call to action for those who felt alienated by the vocal anti-war movement but lacked a platform to express their views. By labeling them the "Silent Majority," Nixon gave this group a sense of identity and purpose, aligning their interests with his administration's war policies.

Nixon's rhetoric was also a tactical response to declining public support for the war. Polling data from 1969 shows that while a majority of Americans initially backed the war, confidence in its conduct was waning. Nixon's speech aimed to reverse this trend by reframing the debate. He portrayed the war not as a misguided conflict but as a necessary struggle against global communism, appealing to Cold War anxieties that still held sway among many conservatives. This narrative shift was crucial in maintaining support, as it tied the war to broader ideological concerns rather than its immediate costs and controversies.

A key takeaway from Nixon's appeal is the power of political messaging to shape public opinion. By focusing on unity and patriotism, he effectively neutralized criticism and rallied a diverse coalition behind his administration. However, this strategy also had long-term consequences. It deepened partisan divides and set a precedent for polarizing rhetoric in American politics. For modern policymakers, Nixon's approach serves as both a lesson in effective communication and a cautionary tale about the risks of exploiting division for political gain. When crafting messages on contentious issues, leaders must balance unity with honesty to avoid alienating segments of the population.

In practical terms, Nixon's "Silent Majority" speech offers a blueprint for rallying support in polarized times. To replicate its success, leaders should:

- Identify shared values among target audiences.

- Frame policies in terms of broader national interests.

- Provide a clear narrative that positions supporters as part of a larger, principled majority.

However, they must also be mindful of the potential backlash, ensuring that their appeals do not exacerbate divisions or silence legitimate dissent. Nixon's strategy worked in its time, but its legacy reminds us that unity cannot be built on exclusion.

Should You Register with a Political Party? Pros, Cons, and Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, initially escalated U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, with broad bipartisan support from Congress.

Yes, the Republican Party generally supported the Vietnam War, though some members, like President Richard Nixon, later sought to end U.S. involvement through policies like Vietnamization.

While major parties initially supported the war, opposition grew within the Democratic Party and among third parties like the Peace and Freedom Party, which consistently opposed U.S. involvement.

As the war dragged on, public opinion shifted against it, leading to increased opposition within the Democratic Party and growing anti-war movements, while the Republican Party remained more divided but eventually supported withdrawal under Nixon.