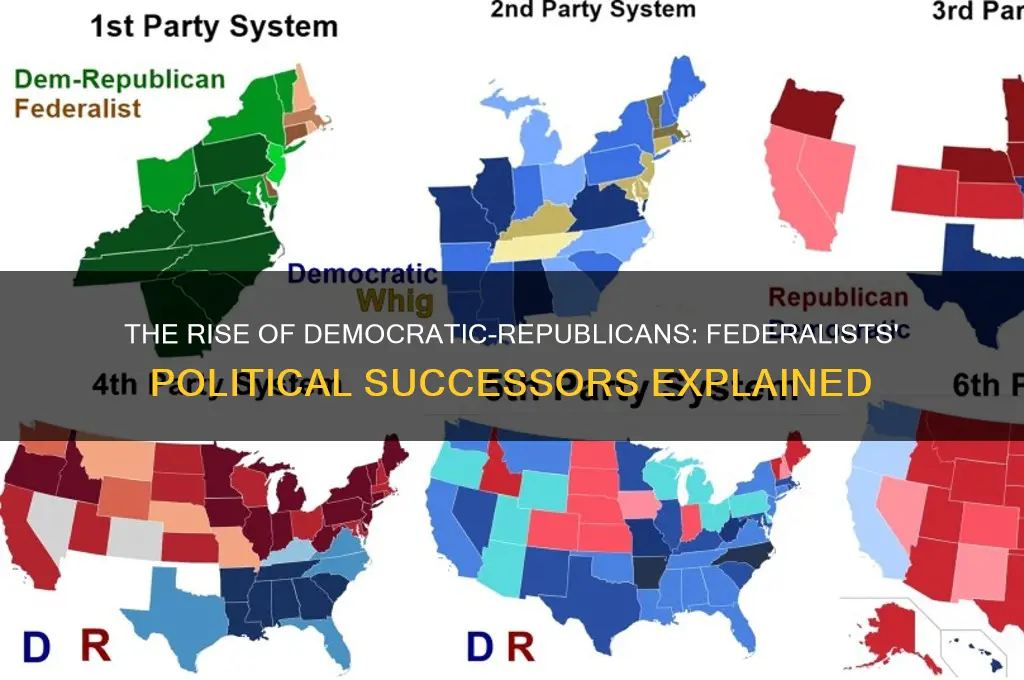

The Federalist Party, which dominated American politics during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, began to decline in the early 1800s due to internal divisions, opposition to the War of 1812, and the rise of new political forces. By the 1820s, the Federalists had largely dissolved as a national party, paving the way for the emergence of the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. However, as the Democratic-Republicans themselves fractured in the 1820s, the Democratic Party, under Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party emerged as the dominant political forces, effectively replacing the Federalists and reshaping the American political landscape.

Explore related products

$14.2 $29.99

What You'll Learn

- Jeffersonian Republicans Rise: Democratic-Republicans led by Jefferson opposed Federalist policies, emphasizing states' rights and agrarian interests

- Election of 1800: Jefferson defeated Adams, marking the first peaceful transfer of power between parties

- Federalist Decline: Overreach, Alien and Sedition Acts, and unpopular taxes eroded Federalist support

- Key Figures: James Madison and James Monroe played pivotal roles in the Republican ascendancy

- Policy Shifts: Republicans reduced federal power, repealed taxes, and focused on westward expansion

Jeffersonian Republicans Rise: Democratic-Republicans led by Jefferson opposed Federalist policies, emphasizing states' rights and agrarian interests

The Federalist Party, dominant in the early years of the United States, faced a formidable challenge from the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson. This opposition was not merely a shift in political leadership but a fundamental clash of ideologies, particularly regarding the role of the federal government and the economy. Jeffersonian Republicans championed states' rights and agrarian interests, positioning themselves as the defenders of the common man against what they saw as Federalist elitism and centralization.

Consider the stark contrast in economic visions. Federalists, under Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and industrialization. Jeffersonians, however, viewed these policies as threats to individual liberty and rural livelihoods. They argued that an agrarian economy, rooted in small farms and local communities, was the backbone of American democracy. This emphasis on agriculture was not just an economic stance but a moral one, reflecting Jefferson’s belief that farmers were the most virtuous citizens, free from the corrupting influences of urban commerce and finance.

To understand the rise of Jeffersonian Republicans, examine their strategic opposition to Federalist policies. For instance, Jeffersonians vehemently opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which they saw as an assault on free speech and states' rights. By framing these acts as tyrannical, Jeffersonians rallied public support, particularly in the South and West, where agrarian interests dominated. Their message resonated with voters who felt marginalized by Federalist policies favoring the Northeast’s industrial and commercial elite.

A practical takeaway from this historical shift is the importance of aligning political platforms with the values and needs of specific constituencies. Jeffersonian Republicans succeeded by tailoring their message to agrarian communities, emphasizing decentralization and local control. For modern political movements, this underscores the need to identify and address the unique concerns of key demographics. For example, a party advocating for rural development today might focus on policies like broadband expansion or agricultural subsidies, mirroring Jefferson’s focus on agrarian interests.

Finally, the rise of Jeffersonian Republicans illustrates the cyclical nature of political power. Federalist dominance was not inevitable, nor was its decline. By offering a compelling alternative vision, Jeffersonians not only replaced the Federalists but reshaped American political ideology. This historical lesson reminds us that political parties must remain responsive to the evolving needs and values of their constituents to maintain relevance and influence.

Why Politics Matters: Uniting Communities, Driving Progress, and Shaping Futures

You may want to see also

Election of 1800: Jefferson defeated Adams, marking the first peaceful transfer of power between parties

The Election of 1800 stands as a pivotal moment in American history, not merely for its outcome but for the precedent it set. Thomas Jefferson’s defeat of John Adams marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing political parties in the United States. This event was revolutionary, as it demonstrated the viability of democratic governance in a young nation still finding its footing. The Federalists, who had dominated the early years of the republic, were replaced by the Democratic-Republicans, a party advocating for states’ rights, limited federal government, and agrarian interests. This shift signaled a broader ideological reorientation in American politics, moving away from the Federalist emphasis on central authority and industrialization.

To understand the significance of this transition, consider the context of the time. The Federalists, led by Adams, had alienated many voters through policies like the Alien and Sedition Acts, which restricted civil liberties and stifled dissent. Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans capitalized on this discontent, framing themselves as champions of individual freedoms and grassroots democracy. The election itself was contentious, with Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, initially tying in the Electoral College, leading to a protracted resolution in the House of Representatives. Despite this turmoil, the eventual transfer of power was peaceful, a testament to the resilience of the Constitution and the commitment of both parties to the rule of law.

This election also highlighted the evolving nature of political parties in the early republic. The Federalists, once dominant, began a decline from which they would never fully recover. Their replacement by the Democratic-Republicans reflected a growing divide between urban, commercial interests and rural, agrarian ones. Jefferson’s victory was not just a personal triumph but a mandate for a new vision of America—one that prioritized decentralization and agricultural expansion over Federalist industrialization and centralization. This ideological shift reshaped the nation’s trajectory, influencing policies from westward expansion to economic development.

Practically, the Election of 1800 offers a blueprint for modern democracies grappling with political transitions. Its success hinged on several key factors: a robust constitutional framework, a commitment to legal processes, and the willingness of outgoing leaders to respect the will of the electorate. For nations today, this underscores the importance of institutional strength and the normalization of peaceful power transfers. It also serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of polarizing policies and the need for leaders to remain responsive to public sentiment. By studying this election, we gain insights into how democracies can endure and thrive amidst ideological divides.

Finally, the legacy of the Election of 1800 extends beyond its immediate political implications. It established a norm that has endured for over two centuries, shaping American identity and global perceptions of democracy. The peaceful transfer of power became a cornerstone of the nation’s self-image, a principle that has been tested but never abandoned. As we reflect on this historic event, we are reminded of the fragility and strength of democratic institutions. It is a lesson in resilience, a reminder that even in moments of deep division, the mechanisms of democracy can prevail—if we choose to uphold them.

Is SAM Truly Socialist? Analyzing the Party's Political Ideology

You may want to see also

Federalist Decline: Overreach, Alien and Sedition Acts, and unpopular taxes eroded Federalist support

The Federalist Party, once dominant in American politics, faced a precipitous decline due to a combination of overreach, controversial legislation, and unpopular policies. At the heart of this decline were the Alien and Sedition Acts, enacted in 1798, which sought to suppress dissent and strengthen federal authority. These laws allowed the president to deport non-citizens deemed "dangerous" and criminalized criticism of the government, sparking widespread outrage. For instance, the arrest and trial of newspaper editor Matthew Lyon for criticizing President Adams exemplified the Acts' chilling effect on free speech, alienating both immigrants and native-born Americans.

Another critical factor in the Federalists' downfall was their imposition of unpopular taxes, most notably the Direct Tax of 1798. This tax, levied on land, houses, and slaves, was not only burdensome but also difficult to administer, leading to widespread evasion and resentment. Unlike the indirect taxes on goods, which were less noticeable, the Direct Tax directly impacted property owners, a core constituency of the Federalists. This misstep eroded their support among farmers, landowners, and the emerging middle class, who viewed the tax as an overreach of federal power.

The Federalists' decline was further accelerated by their perceived elitism and detachment from the concerns of ordinary citizens. Their strong centralist policies, such as the establishment of a national bank and support for industrial interests, clashed with the agrarian and democratic ideals of many Americans. The party's leadership, including Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, often appeared out of touch with the struggles of the common man, fostering a perception of arrogance. This disconnect was exacerbated by their handling of foreign policy, particularly the Quasi-War with France, which many saw as unnecessary and costly.

A comparative analysis reveals that the Federalists' decline was not merely a result of external challenges but also internal miscalculations. While the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, capitalized on the growing sentiment for states' rights and individual liberties, the Federalists failed to adapt their message to the changing political landscape. Their reliance on a strong federal government and elitist tendencies alienated key demographics, paving the way for their opponents' rise. By 1800, the Federalists had lost control of both Congress and the presidency, marking the ascendancy of the Democratic-Republican Party as the dominant political force in the United States.

In practical terms, the Federalists' decline offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of overreach and the importance of aligning policies with public sentiment. For modern political parties, this history underscores the need to balance ideological convictions with pragmatic considerations, ensuring that policies resonate with the electorate. Avoiding alienation through inclusive messaging and addressing the concerns of diverse constituencies are essential strategies for sustaining political relevance. The Federalists' fall serves as a reminder that even the most powerful parties can crumble when they lose touch with the people they aim to govern.

Jussie Smollett's Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Party Ties and Views

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Key Figures: James Madison and James Monroe played pivotal roles in the Republican ascendancy

The Federalist Party's decline in the early 19th century created a power vacuum, and the Democratic-Republican Party, led by key figures like James Madison and James Monroe, seized the opportunity to reshape American politics. Madison, often referred to as the "Father of the Constitution," brought intellectual rigor and a deep understanding of governance to the party. His authorship of the Bill of Rights and his role in drafting the Constitution lent credibility to the Democratic-Republicans, positioning them as guardians of individual liberties and states' rights. Monroe, a skilled diplomat and wartime leader, complemented Madison's theoretical strengths with practical political acumen. Together, they engineered a political ascendancy that would dominate the era.

Consider the strategic partnership between Madison and Monroe as a masterclass in political coalition-building. Madison’s ability to articulate complex ideas in accessible terms—evident in his Federalist Papers contributions—helped galvanize public support for Republican ideals. Monroe, meanwhile, leveraged his experience as a diplomat and war hero to appeal to both elites and the common man. Their collaboration during the War of 1812, where Madison served as president and Monroe as Secretary of State (and later Secretary of War), showcased their ability to unite the nation during crisis. This period, often called the "Era of Good Feelings," saw the Federalist Party marginalized, with the Democratic-Republicans emerging as the dominant force.

To understand their impact, examine their policy legacies. Madison’s presidency (1809–1817) was marked by the Second Bank of the United States, a response to economic instability, and the War of 1812, which solidified American sovereignty. Monroe’s presidency (1817–1825) introduced the Monroe Doctrine, a cornerstone of American foreign policy that asserted U.S. dominance in the Western Hemisphere. These actions not only weakened Federalist influence but also established a Republican framework that would endure for decades. For instance, the Monroe Doctrine’s emphasis on non-intervention by European powers resonated with the party’s anti-Federalist, anti-elitist stance, appealing to a broad cross-section of Americans.

A cautionary note: while Madison and Monroe’s leadership was transformative, their success was not without flaws. Madison’s handling of the War of 1812 faced criticism, particularly the burning of Washington, D.C., which exposed vulnerabilities in his administration. Monroe’s presidency, though popular, saw the beginnings of sectional tensions over slavery, a fissure that would later fracture the Democratic-Republican Party. Yet, their collective efforts laid the groundwork for the party’s dominance, proving that intellectual leadership and pragmatic governance could effectively replace Federalist ideals.

In practical terms, their ascendancy offers a blueprint for political transitions. By focusing on unifying themes—such as national sovereignty, economic stability, and individual rights—Madison and Monroe bridged ideological divides within their party and the nation. Their example underscores the importance of pairing visionary leadership with actionable policies. For modern political strategists, studying their methods provides insights into how to navigate power shifts and build lasting coalitions. The Republican ascendancy was not merely a replacement of the Federalists but a redefinition of American political identity, with Madison and Monroe at its helm.

Understanding Political Parties: A Simple Guide to Their Role and Function

You may want to see also

Policy Shifts: Republicans reduced federal power, repealed taxes, and focused on westward expansion

The Federalist Party, once dominant in American politics, faded by the early 1800s, replaced by the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. This shift marked a profound change in governance, as the new party championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal authority. Their policies directly countered Federalist centralization, setting the stage for a redefinition of American political ideology.

One of the most significant policy shifts under the Democratic-Republicans was the reduction of federal power. Jefferson’s presidency (1801–1809) exemplified this through the repeal of the Federalist-backed Alien and Sedition Acts, which had restricted civil liberties. By dismantling these measures, the Democratic-Republicans signaled their commitment to individual freedoms and state sovereignty. This move not only weakened federal authority but also aligned with their vision of a decentralized government, where states held greater autonomy.

Taxation was another area of sharp contrast. The Federalists had imposed taxes, such as the whiskey tax, to fund federal programs and pay off national debt. The Democratic-Republicans, however, viewed such taxes as burdensome to the agrarian economy. Jefferson’s administration repealed internal taxes and relied instead on tariffs and land sales for revenue. This shift not only reduced the financial burden on farmers and small landowners but also reflected the party’s commitment to a more frugal federal government.

Westward expansion became a cornerstone of Democratic-Republican policy, driven by the belief in a growing agrarian republic. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803, orchestrated by Jefferson, doubled the nation’s size and opened vast territories for settlement. This expansion was not merely territorial but ideological, as it reinforced the party’s vision of a nation rooted in agriculture and decentralized power. Policies like the Homestead Act (though later) were precursors to this mindset, encouraging individual land ownership and self-sufficiency.

However, these policy shifts were not without challenges. Reducing federal power and repealing taxes limited the government’s ability to fund infrastructure and defense, leaving states to fend for themselves. Westward expansion, while celebrated, led to conflicts with Native American tribes and exacerbated regional tensions over slavery. These trade-offs highlight the complexities of the Democratic-Republicans’ agenda, which prioritized ideological purity over pragmatic governance.

In practical terms, these policies reshaped the American landscape, both politically and geographically. For modern policymakers, the Democratic-Republican era offers a cautionary tale about the balance between federal and state authority. While their emphasis on limited government and westward expansion fueled growth, it also sowed seeds of division that would later erupt in the Civil War. Understanding this legacy is crucial for navigating contemporary debates over federalism and national identity.

Why Clapping is Now Considered Politically Incorrect: Exploring the Debate

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, replaced the Federalists as the dominant political force in the United States.

The Federalist Party declined due to its unpopular policies, such as the Alien and Sedition Acts, and its opposition to the War of 1812, leading to its replacement by the Democratic-Republicans.

The Federalist Party effectively dissolved after the 1816 presidential election, as it failed to win significant support, paving the way for the Democratic-Republicans to dominate.

The Democratic-Republicans advocated for states' rights, limited federal government, and agrarian interests, contrasting with the Federalists' support for a strong central government and commercial interests.